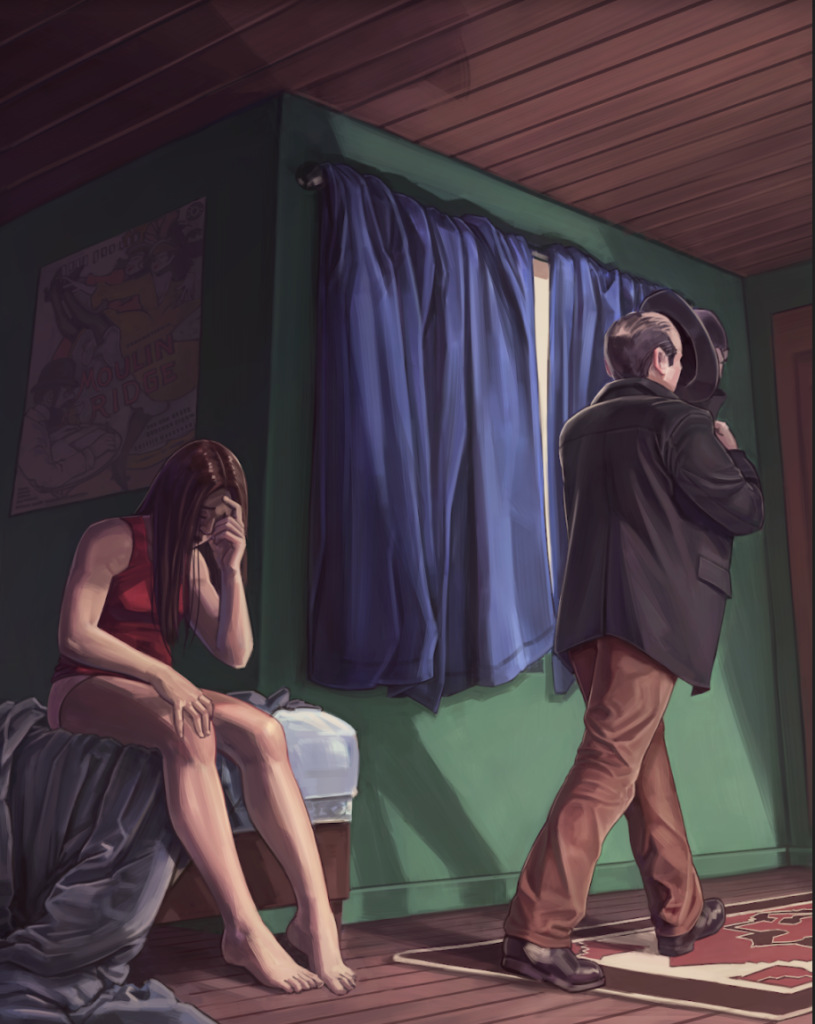

During the early, dark days of the pandemic and amid the ever-endless worry of how to pay my rent every month, I regularly browsed Craigslist to see the latest rental offerings across the U.K. It appears that for a young woman like me (grad student, low-income, “laid-back and open-minded”), there are plenty of cheap, semi-decent looking rooms across the country for a staggeringly low cost, i.e., free. Each advertisement, often titled “free to females” or “free rent for female students,” shares a few common details: the description of the house or room available (ranging from private annexes to shared beds), a few indistinct details about the landlord (“I’m a nice guy!”) and extra bonuses (“access to car,” “phone contract”) [1]. There’s just one condition required. I would have to fuck the landlord.

I can’t say I’m particularly enamoured with the thought of sleeping with my current landlord (no offense, Tim). Yet, it would quiet the ongoing angst every month as I pay over 50 percent of my monthly income for my less-than-impressive four walls and bed. The best-case scenario here would be a free room and tolerable sex, but the worst-case scenario is imaginably horrific.

Over the course of the pandemic, I’ve come across a host of articles reporting the rise of landlords requesting that those “in need of a room” pay with sex in lieu of rent, in cities including London, New York, Honolulu, and New Delhi. This is not a unique consequence of the pandemic. Reports have been appearing over the past five or so years, shedding light on an unsettling feature of the perennially discussed global housing crisis.

The rise in these articles about “sex in lieu of rent” highlights the way in which the housing crisis has now infiltrated the lives of the previously securely housed (i.e. white, university-educated, middle-class women). The reality, however, is that the poor and socially marginalized have suffered from insecure housing for a very long time. These advertisements for “free housing” are the visible surface of sexual exploitation within the housing system.

Despite popular discourse, the institution of marriage was not created to celebrate the love between two people. In The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, Fredrich Engels claimed that marriage became a cornerstone of social organization so white, bourgeois families could combine and preserve capital (which was built on the backs of non-white and/or working-class labor). Owning property fortified the rights of the wealthy while excluding others; only in the late 19th century did suffrage extend to non-property owning white men.

Unable to earn a wage, bourgeois women were provided for by their husbands and in exchange, they were tasked with 1) remaining sexually faithful 2) producing a male heir who would go on to inherit the family’s wealth. At the same time, their husbands were able to pretty much do as they pleased—including having sex outside the marital bedchamber—with no risk to their security or standing. The sex industry thrived as a result of enforced, female-only monogamy, although sex workers were, and continue to be, stigmatized. Marriage therefore was part of an overall system that reified and strengthened economic inequality, and ensured that socio-economic power remained in the hands of the white, male, property-owning class.

Although the laws surrounding marriage and property have gradually changed around the world, heterosexual marriage still dominates as the definitive form of social organization. Governments prioritize marriage and create economic policies that favor married, heterosexual couples, including better mortgage rates, cheaper home insurance, tax savings, and social security benefits. Homeownership, however, which was once held up as the pinnacle of liberal success and self-sufficiency, particularly for married couples, is a distant dream these days for your below-average earners. In both the United Kingdom and the United States, homeownership is in overall decline. A closer look at the breakdown of homeownership numbers elucidates further inequities. According to the U.S. census bureau, homeownership has actually increased in the United States over the past 20 years for all races except African Americans and Native Americans. Nearly three-quarters of the white adult population own their own home, in contrast to less than half of the Black adult population. The lowest homeownership rate was recorded for single females under the age of 25, of whom only 13.6 percent were homeowners.

Economic inequality has increased steadily over the past few decades; the United States has the highest rate of income inequality across all G7 nations (the United Kingdom comes in second). Rising property prices coupled with low, stagnant wages and insecure employment has created a system whereby homeownership is out of reach and government-led austerity agendas have decimated public housing stock. Black, Hispanic, and Native American women bear the brunt of this system. Women living alone or without a partner are subjected to harsh economic realities, earning less than their male counterparts and carrying out the bulk of familial caring duties. The pandemic has hit women’s financial security especially hard, as a recent CNN headline highlights: “The U.S. economy lost 140,000 jobs in December. All of them were held by women.”

In the United Kingdom, the housing crisis (like most of our present-day crises) goes back to Margaret Thatcher. In 1980, her government introduced the Right to Buy scheme, cementing a system whereby shelter is first and foremost a speculative asset. Mass privatization of social housing combined with continually low house-building rates and oversubscription have raised the market value of properties, resulting in a highly sought-after private rental market, a.k.a. a hugely desirable system for landlords. As Laurie MacFarlane writes in Jacobin: “For those stuck in the [U.K.] private rental market, the proportion of income spent on housing has risen from around 10 percent in 1980 to 36 percent today.” This system, marked by a small public housing stock and vastly unregulated housing market, has been reproduced around the world.

While there are indeed many different types of landlord and some of them only have one, two, or 14 extra properties, and a few of them are nice to their tenants and bring them an Easter Egg every year—landlords are nonetheless bad. A 2019 article in Huck magazine by Tristan Cross, satisfyingly titled “there’s no such thing as a good landlord,” examines how “the entire system is weighted in favour of those with the means to become landlords…who both create and profit from the existence of poverty and homelessness.” Landlords generate wealth through a highly unequal system rooted in widespread housing precarity. Their income is dependent on someone else’s labor, and yet landlords still wield immense power over their tenants.

Without a regulated rental system and limited tenant rights, landlords can let houses of substandard quality to people desperate for shelter. Reports over the past few years have derided so-called “rogue landlords” who exploit tenants by charging remarkably high prices for tiny, insubstantial and disintegrating rooms. (Check out Vice’s column which reviews a terrible rental offering every week—in January 2021 they reviewed a studio flat in North London where, according to the writer, you can “sleep in your kitchen and shit in your shower for one thousand human pounds per month.”)

All in all, renters at the low end of the income ladder have a pretty shit time. Stagnant wages, insecure employment, and short-term tenancies keep people on the move, always searching for their next home. Reports continually reveal racial discrimination against Black renters, in both securing a lease and increased rent. The situation is even more dire for trans people, who in the United States have a one in 10 chance of being evicted for their gender identity, and a 20 percent chance of being discriminated against while seeking housing, according to the National Center for Transgender Equality. Hostile environments for migrants mean decent, affordable housing is near impossible; migrant workers in the U.S. are four times more likely to live in overcrowded housing than native-born workers. The United States’ Fair Housing Act purports to prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status, or disability, but lacks meaningful enforcement.

Under these circumstances, the insecurely-housed may entertain the possibility of a sex-for-rent arrangement due to the wider socio-economic logic that economically disenfranchises the vulnerable and expects but invalidates domestic labor, whether that be sex work or housework. Like most commercial transactions under capitalism, sex work is based on the sale and purchase of a commodity, the commodity here being the sexual act. The legality of sex work varies from country to country, but asking for sex instead of rent is illegal pretty much everywhere. It is considered incitement to prostitution and can carry a custodial punishment for the landlord in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

Thinking of sex in lieu of rent as an extension of sex work is helpful in understanding how and why this practice is so pervasive. Molly Smith and Juno Mac’s 2018 book Revolting Prostitutes explains why many people sell sex: it’s usually the same economic need that pushes people to wage labor, but with even fewer protections. Smith and Mac state that “the person selling sex needs the transaction far more than the buyer does…desperation makes them less able to refuse unfair demands.” And landlords know this.

How is the equitable value of a room judged in terms of sexual services? Clicking through landlords’ advertisements, the terms of the sexual arrangement are rarely detailed online but are something to be worked out in further discussions. Some are explicit in asking for sexual acts (ranging from oral to penetrative sex) to be provided a certain number of times per week, whilst some desire an “organic” process, meaning the terms will be negotiated as the relationship develops after the tenant moves in. Others ask for a “live-in girlfriend” or a “house boy” which implies wanting someone to take care of the housework as well as a lot of “stroking and making out.” Nearly all ads posted online request a photo of the potential tenant. The fear of an unequal transaction is expressed in an enlightening thread entitled “there is nothing wrong with sex-for-rent offers” on Reddit, whereby a user writes that sex in lieu of rent is “Terrible value for the landlord…Unless their tenant is a supermodel.”

In an undercover investigation, BBC journalist Ellie Flynn posed as a student at the University of Manchester in search of a room, meeting up with men advertising this kind of exchange [2]. Her assumptions about the type of men seeking these services were turned on their head, commenting that “It’s easy to assume these landlords would be lonely and older, but one guy was my age and another was younger than me, so there was a huge variation in age.” What united these sex-seeking landlords was their interest in power over their potential tenants. She reflected, “I think in a lot of cases it’s about power, a lot of the landlords liked the fact that whoever they were getting couldn’t leave, they almost wanted someone that couldn’t say no. They had an entitlement to sex and weren’t thinking about where they were getting it from … and then in some cases it was people being genuinely lonely, but still having that sense of entitlement. They didn’t think about the person they having sex with.”

In the same Reddit thread discussing the complexities of the sex-for-rent transaction, a more astute user writes:

You can rent to a tenant in exchange for sex, or you can rent to a tenant in exchange for money which you then spend on sex workers. Why would anyone choose the first instead of the second? This is the balance of power argument again: you choose the first one because the tenant is vulnerable and dependent on you. They have less ability to say no without consequences than a sex worker who you’ve texted.

A user named “serculis” added, “It is morally wrong if the tenant has to continue having sex with the landlord even if they stop wanting to (because they don’t want to get kicked out), but in technical terms, isn’t that something they have to put up with for signing up to the contract in the first place?”

Oh man. The desire spoken of here is really about putting someone in a position where they can’t say no. That no is rendered obsolete because of economic insecurity. These “technical terms,” i.e., a verbal contract between landlord and tenant, is perceived as binding. Even though this contract is explicitly illegal, the agreement―based on an exchange of services―is held to be of greater worth than a person’s autonomy over their own body.

A young man who exchanged sex for rent in the south of England spoke of his experiences for Buzzfeed and described the difficulty of navigating consent when sex was requested: “There’s a kind of underlying pressure…that makes it much more complicated and more difficult… It becomes blurred.“ He was forced into situations where “he didn’t have the strength to say no,” adding, “I felt more worried about upsetting [the landlord] than I did my own self-respect.”

How we judge these transactions is connected to our socio-cultural beliefs about sex and sex work. Feminist arguments straddle both sides of the sex industry abolition debate, oscillating between those incorporating “free choice” and “pro-sex” arguments, and those wanting to shut the industry down via more punitive policing. Defenses of those engaging in the buying and selling of sexual services—whether involved in rent-for-sex operations or more classic forms of sex work—often focus on the individual agency of the people involved. Buyers are often described as lonely and so low in self-esteem that buying sex is their only way of connecting with another person. For sex workers, selling sex can be a positive and financially lucrative experience, and potentially no more demeaning than other wage labor. The anti-sex work argument, on the other hand, insists that sex can never and should never be considered work.

Without making a judgment regarding whether selling sex is “good” or “bad,” Smith and Mac argue that sex should have a regulated economic exchange value to ensure protection and increase individual agency for the most vulnerable workers. As long as sex is sought outside non-transactional relationship practices, sex workers need protection. Full decriminalization and labor rights for sex workers would help ensure less exploitative working environments. Assessing how the proliferation of rent-for-sex would be affected if sex work were recognized as labor is a hypothetical task, but it creates a clear boundary that affirms the provision of sexual services as work in situations whereby people are already—even if they don’t acknowledge it—treating it as such.

Over the course of the pandemic, most governments have told us to stay home. According to those in power, home is our safe space, free from the potential dangers that lie outside. However, little has been done to ensure that homes are available, affordable, stable, and secure. With radically reduced incomes and millions of jobs lost, rent debt has soared. Anxiety about housing has added to the anxiety caused by the pandemic itself.

In a brief moment of lucidity a few days after the implementation of the first national lockdown, the U.K. government sheltered the majority of unhoused people on the streets, placing them in empty hotels and B&Bs. This easy fix to our manufactured housing crisis shows what could be done to prevent widespread housing insecurity. We could solve this crisis by injecting our social housing system with funds; we could treat housing as a necessity for survival rather than a means for generating profit. Investment in social housing and public services is an integral first step.

Under the current pervasive logic, however, the insecurely-housed continue to lose out in the housing system and in the sex industry, both which are underpinned by the preservation of private property. Landlords exploit tenants and are able to make, bend and break the trajectory of people’s lives. We need to eradicate the power of landlords, so they can stop fucking us over, and stop fucking us.