Triggering the Right: The Role of Language in the Culture Wars

Often words can obscure as much as they reveal. That’s just how the right likes it.

“The Lancet published this bs?” may be the least favorable review my writing has ever received. The reviewer was Tyler Cowen (a right-wing economics professor) and the bullshit in question was an academic paper. (The paper, by the way, was not published by the Lancet, but in a spin-off journal: the Lancet Planetary Health.) Cowen was not alone in disliking the paper. Maxine Bernier, leader of the right-wing People’s Party of Canada, tweeted that the Lancet had been taken over by “far left crazies.” Conservative commentator Ben Shapiro retweeted a similarly disparaging tweet from Charles Fain Lehman, researcher at the free-market think tank the Manhattan Institute. Claire Lehmann, founding editor of the right-wing magazine Quillette, retweeted economics professor Chris Auld, who simply said: “This is taking space in a medical journal.”

Going viral with the right was a surprise because the article in question is based on another that I’d written for popular media, one that was generally well received. Originally published by the Conversation, it was republished by the BBC and others and has been read by around a million people. It was widely covered in the press. I spoke about the contents on the French news and was quoted in Scientific American. The argument of both papers is the same: neoliberalism prioritizes market value above all else. This meant that although neoliberal economies have unprecedented productive capacity there were barriers to using this to protect health, and this created problems in dealing with the pandemic. So why did one article trigger the right, while the other was ignored by them?

Capitalist Realism

Most people do not read, hear, or talk about capitalism. In day to day conversation, the capitalist economy is simply “the economy.” As in, we have to save the economy. Or, “how has the economy affected you this year?” In each case, what is being referred to as “the economy” (the way we produce and distribute goods and services) is actually “the market” (buying and selling things in order to make money). This fits the neoliberal capitalist idea of the economy: buying and selling things for a profit is economics. Making and distributing things in non-monetary ways (e.g. when the state provides healthcare, or when our households feed family and friends) is… something else, and probably bad.

Capitalism as a mode of production organized around making a profit is young, though precisely dating economic systems is tough. We can see lots of things that look capitalistic in many societies at many different times. Saying exactly when a society goes from having some capitalist elements to being capitalist is much harder. That said, there is general agreement that Europe was still feudal in the 1500s, managing its economy via a system of peasants and lords. Around 1700, historians begin to point to the transition to a period of prolonged capitalist growth in Europe. But at this same period China, although it had an advanced commercial economy, is not generally thought to be capitalist. Neoliberal capitalism, characterized by use of the state to further expand markets into new areas of life, is even younger. For example, the move to marketize universities or to create markets as a way to deal with pollution only dates back to Thatcher and Regan in the 1980s.

Describing neoliberal capitalist institutions, values, and beliefs as “the economy” hides the fact that neoliberal capitalism is a specific way of organizing the production and distribution of goods and services. By calling this specific system the economy we obscure from view that fact that other systems have existed. In turn this depoliticizes the economy, transforming it from a set of stories and social relations that can be changed into something that has always existed— something external to society that we can do little to alter.

A depoliticized view of the economy is most vividly captured in a series of interviews for the charity ECNMY. Asked what they pictured when they heard “the economy,” one interviewee said, “The economy feels like an organism. I mean a giant blob or mass that feels like it has its own consciousness. Perhaps it’s more of a monster.”

The phenomena of most people coming to see the economy as a monster that must be protected and placated rather than transformed and replaced is known as capitalist realism. The term “capitalist realism” is a riff on socialist realism, the political doctrine imposed by Stalin in the USSR. Socialist realism declared that all art must further the socialist cause, presenting an idealized and simplified vision of socialist life not as it was but as it should be. Capitalist realism acts similarly, but is not confined to art and is not an explicit state diktat. Capitalist realism acts through the various cultural industries that depict life under capitalism in idealized forms—for example, the advertising industry.

The effect of advertising as an industry is to reinforce key myths on which capitalism relies—and in doing so, to make it harder for us to picture non-capitalist ways of living. Adverts suggest to us that buying things is the best way to become the person we want to be. Want to be a good child? Buy your mother a Nespresso machine. Want to be a cool, adventurous, always-there-for-her-kids mom? Buy a Toyota. Want to not forget your dead wife? Get a Google assistant! Every single day, adverts bombard us with messaging that reinforce the ideals of capitalism.

The constant reinforcing of neoliberal capitalist values and ideas by the advertising industry and the political right is buttressed by an absence of anti-capitalist thought and ideas in most of our daily lives. When popular media or academics discuss “the economy” rather than the capitalist or neoliberal economy, this creates a kind of “negative” capitalist realism. By hiding the historically specific nature of capitalism, talking about “the economy” reinforces the myth that capitalism is the only possible economic system. And by depriving us of the recognition that the economy we have is not the one we have always had, such newspapers, television, and academic writing deprive us of spaces to find alternatives to the values embodied in capitalist propaganda.

Puncturing capitalist realism

My article in the Conversation contributed to a negative capitalist realism. Although it discussed ideas of value and the limits of markets, its tone and language were muted. This was a conscious choice. Myself and my editors were keen to ensure the article was read by people not already on “our side.” Although “capitalism” is mentioned, this only happens late in the article when I discuss possible futures, rather than as part of the analysis of the economy today.

By talking about “the economy” rather than the more accurate “capitalist economy,” the article creates a void into which the reader projects their ideological commitments rather than challenging them. After the article was published, I was contacted by both a revolutionary communist party and representatives from a Fortune 500 company. This illustrates the inherent trap of imprecise language drawing on a radical theory. Yes, you get it in front of new audiences. But it does not necessarily challenge them. Radical theory can simply be co-opted into capitalist practice. To illustrate, I have been approvingly quoted as saying we need to give people agency and control over their own lives in a report on how companies can profit from “new lifestyle shifts” after COVID-19.

The Lancet Planetary Health article, on the other hand, has not been a source of consulting opportunities for me. The analysis is the same, but the language is different—it is explicitly an attempt to puncture capitalist realism. I name the current economy as neoliberal capitalism, and point to sources of alternative ideas and values.

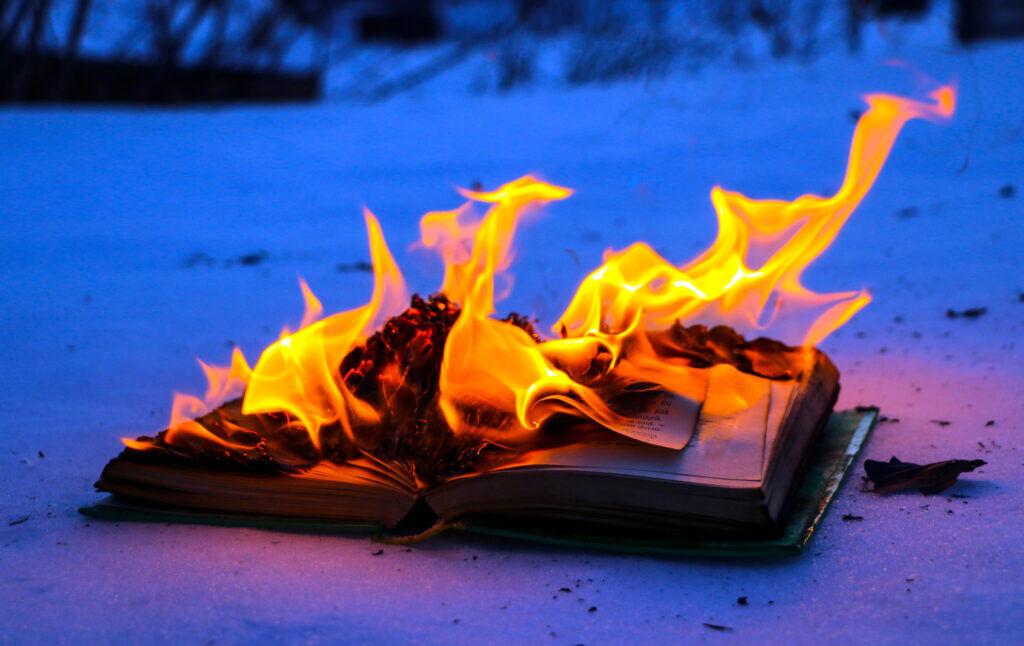

Naming neoliberalism and capitalism is the first step in breaking capitalist realism’s hold over us. By using historically specific terms, we are implicitly highlighting that the economy as we know it today had a starting point. This is useful because it drags the idea of the economy into the realm of time. No longer is the neoliberal capitalist economy something outside of the cycles of birth and death that govern all life. Instead it is something that began. And things that begin are things that can end.

Understanding capitalism as time-bound is not enough. Knowing that something can end does not tell you anything about how it might end. This is where the language of critical disciplines like ecological economics, feminism, and Marxism become useful.

Ecological economics, feminism, and Marxism all take issue with capitalist conceptions of value. They critique and deconstruct it. Ecological economics argues that more is not always better. That in the pursuit of quantitative increases in monetary value, we lose something of the qualitative values of life: the expansion of capitalism has been made possible by the destruction of aesthetic, life giving, and intrinsic values of nature. Ecological economics suggests that there may be other ways to live that are not premised on the relentless expansion of consumer goods.

Feminist economics points to the inherently social nature of any productive activity. The “economy” is not simply states and markets, rather it is a system by which we produce and distribute goods. Markets would not function without households: workers do not spring fully formed from the ether. They are born and raised in social units. The “rational” market is ultimately nothing without the many non-monetary, “irrational” relationships involved in caring for one another.

Marxist economics highlights that ultimately all value captured by capitalists is rooted in the work of their employees. Without employees no business can function. We are the productive heart of any economy. Workers create and do. The product of this work is then removed by a capitalist class who work (through the cultural industries) to keep workers divided and controlled. Marxism points to our role in capitalist and non-capitalist societies: neoliberalism paints us as consumers, yet we are also producers.

Each of these schools of thought has much more to offer than I can cover here—these are the key ways they have shaped my own thinking. But even in these snippets I hope you can see the possibilities. You need not agree with all of Marx to see value in the way his analysis of capitalism provides a way to begin to look beyond capitalism.

Triggering the Right

Pointing to alternative values and ways of organizing the economy is triggering to the right because it threatens the cultural basis of capitalism. The effect of talking about neoliberal capitalist systems in ways that remove its history and politics is to provide cultural conditions in which capital can accumulate. Adverts that tell us that the best way to show our love is by buying things; news sites that have a “business” section but no “union” section; politicians that argue the U.S. can’t afford single payer healthcare. These are all expressions of neoliberal values that serve to help the capitalist class make money, and in this way are useful to the political right wing.

The reason advertisers want you to buy something rather than do something as an expression of love is not because they don’t think doing things is effective—they just don’t make money from it. Your ability to put food on your plate and keep a roof over your head depends more on political decisions about how we distribute goods than some inherent quality of your employer. But news sites want you to focus on how well your employer is doing, rather than taking concrete steps (join a union!) to shift the balance of distribution. Framing discussions of healthcare around affordability reinforces the idea that we have to manage the economy in monetary terms, allocating on ability to pay rather than need.

Providing a direct challenge to capitalist ideals and values undermines the conditions that the right needs to flourish. It is not enough, on its own, for us to say “this is neoliberalism.” It is not enough to show where alternatives lie. But these things are essential first steps. It is only when we have an appropriate language to describe our present and our future that we can take meaningful steps that destabilise the right wing consensus that dominates our politics today.