The Orwellian Language of the Animal Industry

Truthful lies, respectable murder.

The coronavirus pandemic has revealed new shades of ugliness in the meat industry. Seven managers at a Tyson Foods “pork plant” in Iowa were fired for placing bets on the number of employees who would catch COVID-19. Between these jolly gambling sessions the same managers offered $500 bonuses to workers who never missed a shift, essentially incentivizing them to contract (and spread) the virus. In the U.K. the Guardian revealed that the animal industry has misled health authorities about the startling extent of coronavirus at their “meat processing plants.” These cases should disturb any interested onlookers. By indulging in chicanery, tinkering with virus reports, and jeopardizing the wellbeing of workers, the animal industry has treated employees, the general public, and elected officials with contempt. However, despite all the gross indifference, data-fudging, and subterfuge it was the description of the slaughterhouses as “food factories” that grabbed my attention, and made me think of Orwell.

I would describe Orwell’s 1946 “Politics and the English Language” as a landmark essay, but he would never forgive the use of such a rancid cliché. It is an abiding and amusing irony that a writer as unique as Orwell, a socialist revolutionary best known for his scathing criticism of the USSR, has become such a dull prop, a meme-worthy, yawn-inducing bore brandished by every political hack and their grandmother. Yet his clichéd usage paradoxically stems from his uniqueness as a writer and his chastising of political euphemism remains ever relevant.

“Political language,” Orwell observes, “[…] is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” No thoughtful observer could fail to agree, or to recognize the continued relevance of his critique. Political euphemism is always levied to disguise something which, plainly described, would strike most observers as disgraceful. It is therefore incumbent on the public and the media to sniff out euphemisms and expose them wherever they are. So, where are they?

Of course, torrents of murky dribble continue to stream out of politics. The U.K. Brexit debate was pregnant with such statements. There was the People’s Vote campaign, wherein “the People” meant the anti-democratic minority; the “Irish problem” which was in fact a British problem carried by an English vote; and Theresa May’s infamous “Brexit means Brexit”—I wonder if such an unhelpful tautology has ever been uttered. The most insidious euphemisms, however, always cover for violence. The U.S. police have had to rebrand parts of their arsenal of weaponry from “nonlethal” to “less lethal” (afterward, those weapons were used during the BLM protests of the summer of 2020 to blind and maim protestors and journalists). China distorts democracy protestors into “violent criminals” who anyway enjoy “unprecedented democratic rights.” Nations continue to “defend their interests” rather than “shoot rival soldiers to bits,” and “collateral damage” becomes the state’s description of choice for the negligent murder of bystanders.

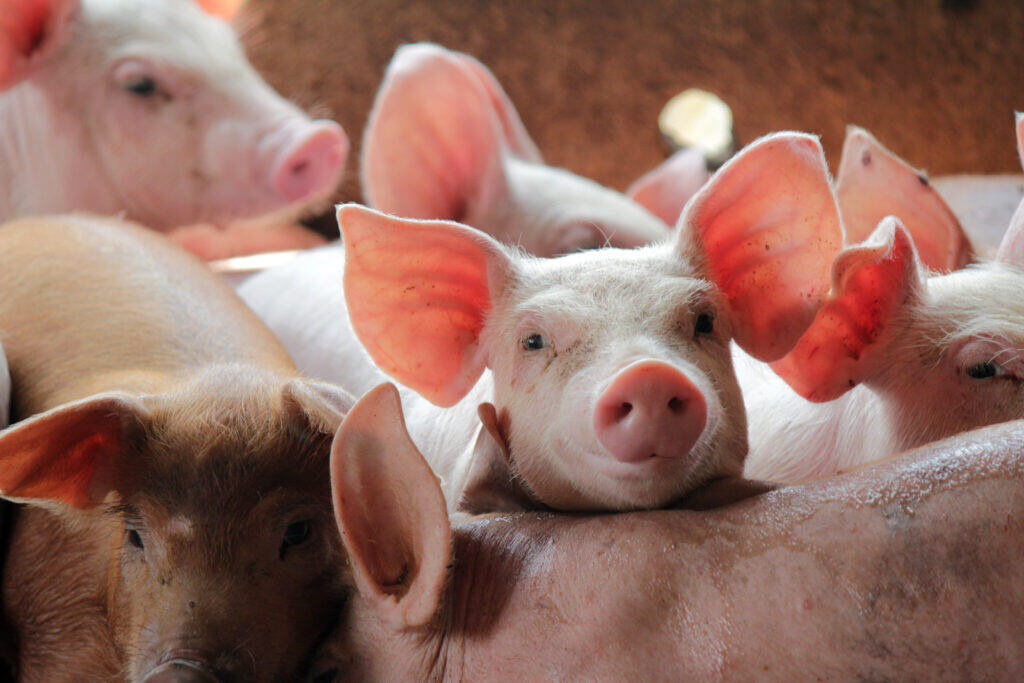

Yet for all the unctuous prose which permeates the halls and hippodromes of politics there remains another massive offender when it comes to devious language—animal agriculture. The animal industry’s attempts to disguise standard industry practices are relentless, and understandably so. The vast majority of people who consume meat and dairy are not wantonly cruel, though many suspect that procuring meat is an untidy business. However, presenting the life of a pig from pen to plate, or describing meat industry standard practice in the lucid tones of regular Anglo-Saxon makes many a consumer blanch, and the industry knows it. Translation is therefore required to provide consumers with accurate information about how their food is produced.

The meat industry’s obscurantism can verge on the absurd; slicing off a chicken’s beak is described as “beak conditioning.” The men who slaughter the chickens who survive the “automatic killer” machine have been rebranded from “backup killers” into “knife operators.” It sounds as if they could be roughly chopping vegetables. The word “insanguinated” sounds louche, elegant, and reminiscent of “inebriated.” I wouldn’t intuitively shudder if I heard a chicken was to meet this fate, although the term means “bled to death.” We are told that animals undergo “humane slaughter” when thousands of chickens are frozen or boiled to death and animals being skinned alive is commonplace. “Slaughterhouse” is replaced by “meat plant,” and that’s exactly how animals are visualised—as plants, whose rote killing is described as a “harvest.” I hope you don’t feel patronized if I point out that the inside of an abattoir is rather different to a field of summer corn.

Orwell makes the case that the use of Latin, Greek, scientific, or jargon words “fall upon the facts like soft snow, blurring the outlines and covering up all the details.” Although describing abstract ideas and sensations tends to conjure fancy words, there is nothing mystical about the methods of animal agriculture, nothing so enigmatic as to merit the word “insanguinated.” To seek the truth is to call a spade a spade, even if the meat industry would rather call it an “earth redistribution device.”

The animal industry may flourish on euphemisms and word-games, but it did not create all of them. Many slippery words were introduced into English due to, of all things, the outcome of the Battle of Hastings. Post 1066, the English ruling class became French-speaking Normans, whilst the Saxons generally remained as lowly farmhands and huntsmen. As a result of this class divide the names of living animals like “pig,” “cow,” “sheep,” “deer,” and “calf” retained their Saxon character, as interaction with living animals generally remained in the world of peasant farmsteads. Meanwhile, cooked animals, served up to dukes and barons on the family silver, gained French names: “pork,” “bacon,” “beef,” “mutton,” “venison,” “veal.”

These words may not have been coined by animal industry spin-doctors but their effect is the same. They turn cooked meats into a distinct category of object, obscuring their animal origins. Orwell shows disdain for the uncritical “notion that Latin or Greek words are grander than Saxon ones,” especially when words as delightful as “snapdragon” (a type of flower) are replaced with sterile, scientific words like “antirrhinum.” The Latinized Norman terms for cooked meats may now be a part of established English vocabulary, but some alternative history-writing can get us closer to the truth. If we pretend Godwinson and his housecarls won at Hastings, and excise these intrusions from our dictionary, then we observe plainer, more honest results. So “pork” becomes “pig corpse,” “bacon” is “slices of pig belly,” “beef” is “cow flesh,” “mutton” is “sheep muscle,” “venison” is “deer cadaver,” “veal” is “baby-cow hunks.” If such terminology doesn’t sit easily, then interrogate your feelings—each description is accurate.

Orwell also noted euphemism’s common mutation into lying. When people have vested interests or dogmatic attachments to organizations then lying becomes necessary to save face. In The Prevention of Literature Orwell points out that if history was to be revised and edited by the Soviets, so that pamphlets from the time of the Revolution (1917-18) praised Stalin instead of the cadre of Old Bolsheviks who would later become his victims, then “no Communist who remained faithful to his party could protest.”

The same is true of the animal industry, which can never honestly evaluate its own practices. To do so would mean confronting the destruction of animal life and ecology on an indefensible scale and slashing the profits of a global market which, between meat and dairy, is worth around $2 trillion. As Upton Sinclair, author of vintage meat industry exposé The Jungle, would have it: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” So instead the animal industry blames its opponents—soy-guzzling vegans need to switch to cow’s milk to save the planet because soy crops are destroying the Amazon. No matter that 75 percent of deforestation in the Amazon is done to create pastures for farmed animals; no matter that 96 percent of the soy grown in the Amazon goes to feed cows, pigs, and chickens. When scrutiny is applied to this cabal of amoral business interests, the courtesy of euphemism is forsaken and replaced with a cascade of lies the size of Niagara Falls.

Orwell tried to root out falseness and hypocrisy wherever he found it. Yet let me not offer a misleading view of him: he is on record about vegetarians, whom he described in The Road to Wigan Pier as being among “that dreary tribe of high-minded women and sandal-wearers and bearded fruit-juice drinkers who come flocking to the smell of ‘progress’ like bluebottles to a dead cat.” Even the most pugnacious vegans should drop their bayonets and chuckle at such a wonderful description.

However, ultimately I submit that Orwell was unreflective in his view of animals. Here is a man who could write in “Shooting an Elephant” that “I did not want to shoot the elephant. I watched him beating his grass against his knees, with that preoccupied grandmotherly air that elephants have. It seemed to me that it would be murder to shoot him.” Or later, as the elephant struggles for life: “It seemed dreadful to see the great beast lying there, powerless to move and yet powerless to die, and not even being able to finish him. […] The tortured gasps continued as steadily as the ticking of a clock. In the end I could not stand it any longer and went away.” Should he really be so scathing about the vegetarian cause?

Orwell’s own example reveals the most intransigent problem. Despite feeling great reticence he shot the elephant, “solely to avoid looking a fool” to a crowd of Burmese onlookers. It is sobering that even a mind as alert and principled as Orwell’s could cave in to pressure to conform. The demands on Orwell, a white policeman in colonial Burma at that time, to legitimize himself through violence may not be as alien as they first appear. The desire to conform to type, to be “normal,” is a potent one; if you aren’t normal you’re an outcast, a pariah, a freak. The expectation for animals to die for us remains strong, and euphemisms are one tool that ensure this expectation persists undiluted. Euphemisms make it easy to avoid thinking; they help people to take the smiling farmyard creatures which dot the packaging of some tortured cut of meat at face value. Even when people suspect something is wrong, when they intuit that gassing a pig or shooting an elephant is probably quite a cruel thing, they can proceed to do it anyway, driven on by the expectations of a culture, economy, or society. Orwell grasped the helplessness of conformity, that even an imperialist can be a marionette of his own making, desperate to impress the downtrodden, straitjacketed by his own desire to appear formidable and reduced to “a hollow, posing dummy […] He wears a mask, and his face grows to fit it.”

It remains true that no matter how genteel the animal industry makes its language, no matter how many smears and fake factoids they excrete, most people horror at the sight of an animal suffering —elephants yes, but pigs, cows, and chickens too. Yet despite mankind’s fondness for animals, when the dinner bell trills they vanish from our minds like vapor. Even if we swaddle ourselves in thousands of comfortable euphemisms the facts of the “meat processing plant” will not alter. Orwell, like most people, looked at meat and saw food, like he looked at vegetarians and saw cranks. He did not realize, or chose not to see, that meat is the groans of dying elephants, of chickens plunged in scalding-tanks, of pigs writhing in harvest.