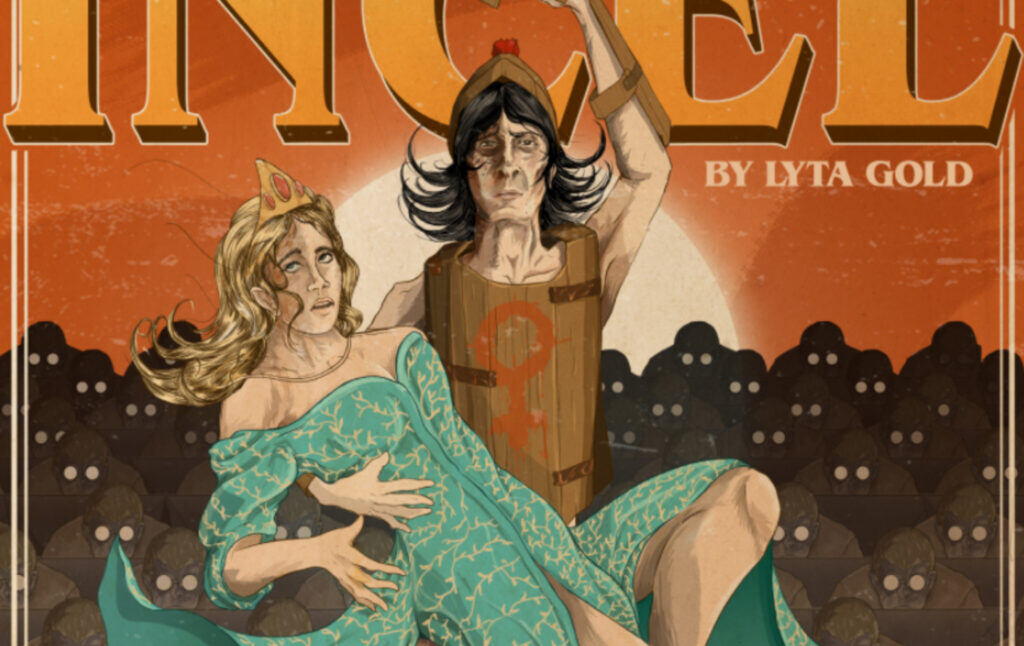

Inside the Incel

“I am human and I need to be loved

Just like everybody else does.”

The Smiths, “How Soon Is Now?”

Should we have sympathy for incels?

I hate to ask the question, but I have to get it out of the way. It’s the first—and often the only—concern people have when discussing the incel subculture. “Pity the poor young white man,” begins the scathing Rolling Stone review of TFW No GF, a lopsided documentary about incels which tilts hard to the side of sympathy. Certainly, incels—or “involuntary celibates”—began life on the internet in a very sympathetic way, as members of a support group for lonely people who had trouble finding love. It was only later that the word exclusively came to indicate a group of angry, solitary, sexless young men who enjoy bad memes and once in a while commit mass murder. In an interview with Alana, the queer woman who started the first incel forum, Reply All host PJ Vogt clarified that “because the [incels] who are angry and violent take up so much space, it feels like it’s now hard…to talk about the problem of loneliness, because what I think some people hear is ‘Oh, you’re asking me to feel bad for a bunch of violent misogynists.’” Vogt’s anxiety is understandable: the initial reaction to any conversation about incels is always to clarify if we are supposed to feel bad for them, or to neatly separate out the evil (violent misogynist) ones from the good (merely sad) ones. In this, discussions of incels tend to be very like discussions about Trump voters: are they a basket of deplorables, lost to decent society forever, or Forgotten Men who can be saved?

This framing is really the result of a larger cultural pathology around the concepts of “pity,” “understanding,” and “forgiveness.” Human beings are complex, and any attempt to sort people into the twin categories of pitiable victims or permanent villains is inherently doomed. Yet this question—“how should we feel about incels”—suggests another—“what should we do about incels?”—which, though it sounds very practical and helpful, also has had a tendency to lead to some foolish and doomed places. If, for example, it could be fairly argued that incels are the inevitable result of the economic and cultural misery of capitalism, then would socialism be able to hand out girlfriends? Are there some problems that socialism can’t solve? Or are we still asking the wrong set of questions?

In a non-plague year, TFW No GF would have premiered at SXSW, the exciting debut of a talented young director. Alex Lee Moyer’s film is beautiful and expressionistic, relying on mashups of memes and long text scrolls to illustrate the feeling of being a lonely person with only the internet for company. Josh Gabert-Doyon’s review in Jacobin praised the film’s “tender” and “compassionate” portrait of its subjects, five young white male dropouts who are suffering from depression, boredom, loneliness, isolation, suicidal ideation, and all the other miseries that descend on those who fail out of the school-to-college-to-good capitalist job pipeline. “What makes Moyer’s documentary stand out,” says Gabert-Doyon, “is her effort to situate her subjects within a broader socioeconomic context. Incels, in TFW No GF, are not just woman-hating ‘shitposters,’ they are also complex subjects born out of a post-economic crash United States, steeped in a culture of resentment. While this contextualization doesn’t explain away the worst of incel culture, it contributes to a much richer portrait, and Moyer’s interviewees are shown to have some self-reflexivity on this account as well, analyzing their own cultural and socioeconomic identities.”

The only trouble with TFW No GF is that it’s a big fucking lie. For one, as Rolling Stone points out, the film was produced by Cody Wilson, a 3D-printed gun manufacturer with ties to white supremacists who “[pled] guilty to injury to a child after having sex with an underage girl, a plea that required him to register as a sex offender.” The film generally downplays the raging misogyny of inceldom, explaining it away as edgy jokes for attention, and describes the few incel murderers as the sort of people who “forget that they’re playing a character. The next thing you know they end up at a place like Charlottesville.” The racism endemic to incel communities is even more suspiciously erased; beyond that passing reference to Charlottesville, you have to peer closely at the rapidly scrolling 4chan text to pick up phrases like “muscular colored kids.” One of the subjects, a denim-clad Texan named Kyle, wears a bejeweled confederate flag ring and claims that he felt alienated as a child because half his classes (in El Paso) were taught in Spanish. This usage of Spanish, he implies, drove him into the arms of video games and unsuccessful homeschooling. As an adult, jobless and depressed, he reports getting into fights in El Paso (which is, he tells us “a Mexican town” and they’re “all about the fucking machismo.”) Is Kyle a white supremacist? Moyer never appears to ask, and Kyle never says. The complete lack of follow-up here raises significant suspicion about the filmmakers’ intentions—and, given Wilson’s history, suggests that he may have had an ulterior motive in producing a documentary about incels that downplays their bigotry.

But the biggest issue with TFW No GF has to do with a little game I like to play called “who pays the fucking rent.” One of the subjects mentions that he has two jobs, and lives with his mother who has cancer; the others allude to possibly having been employed in underwhelming jobs at some point, but, as they regularly use the term NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) it’s unclear if they have jobs at the time the documentary was filmed. Initially, Kyle is unemployed and on food stamps; after moving back in with his family, it seems that they pay his bills, though this is never stated directly. None of the subjects live in particularly nice locations, but they have apartments, and internet, and desktop computers upon which they spend most of their time. Two have an impressive collection of guns, which can’t be cheap. Money is coming from somewhere, but its source isn’t really explored. It seems very likely that some relatives are taking care of or connected to these young men, but they’re completely invisible. Refusing to include the family members is more than a simple aesthetic choice, and once again casts doubt on the filmmakers’ intentions. Are these young men actually as isolated as they seem? Are they as impoverished as the narrative implies? The answer to both questions may very well be “yes,” but if so, leaving the families out makes little sense. If the intent of the documentary is to provide a full portrait of why these young men are so lonely, and to connect it to economic immiseration, surely it makes sense to simply explain who pays the rent.

And Moyer definitely spoke to the families. The documentary is littered with footage of the subjects as children: lots of photographs, and even home videos. Where did Moyer source this material? Not, I think, from the subjects themselves—what young person keeps an extensive trove of their own baby pictures, school photos, and videos of themselves at age seven looking sad? The documentary does not interview anyone besides the five young men; according to Rolling Stone, this was “per the subjects’ request.” But Moyer must have talked to their mothers, or asked the subjects to reach out themselves for the photographs and the home video footage. The absence of the mother or any other relative weighs heavily, as in a fairy tale.

Ultimately, TFW No GF, much like inceldom itself, is a fairy tale, or can be understood best in those terms. An incel that goes by “Egg White” laments “the happy family, the white picket fence—that’s on its way out, I’m afraid…women, they’re out there and they’re taking the good stuff…” He doesn’t elaborate on how exactly women have contrived to steal away an American dream that never actually existed; instead, he laments the sexual freedom of women on Tinder, hopping from hot guy to hot guy, saying that guys like him can’t “catch up.” Ultimately, the incels’ problem isn’t loneliness or economic hardship, or to be more specific it isn’t only loneliness and economic hardship. They’re sad that they’re not successful or talented, not better than other people. They feel “unnoticed” and “abandoned,” “raised with complete anonymity their whole lives.” As one who goes by “Kantbot” puts it: “People used to like, graduate from high school and go get a job or whatever, and things worked out pretty well for them. But now that’s fucking impossible. You have no experience in anything, and you’re from like a small-town background and you don’t have any connections. So you just end up back at home, and your parents are telling you to go apply at McDonald’s or something.”

Now, in the white picket fence fantasy, someone works at McDonald’s, just not these guys. McDonald’s of course, is beneath them. They were supposed to have had the good jobs. In that ideal world they would still sometimes visit McDonald’s, as they breeze in on a road trip in the nice car purchased thanks to the good company job, accompanied by the economically dependent wife and 2.5 worshipful kids. That’s the life they’re mourning.

“Aha!” you might say. “Incels are however misguided still affected by market forces, by the crushing immiseration of capitalism. Ergo, we should feel sorry for them; ergo, socialism would fix their problems.” I am again uninterested in the question of sympathy. I am, however, interested in what we mean when we say that someone has been affected by capitalism and market forces. Wouldn’t it be stranger if incels weren’t alienated by modernity? As Gabert-Doyon puts it in Jacobin: “In part, then, the men in TFW No GF point toward the failures of a market-based logic of individual freedoms and responsibility.” Well yes, but what doesn’t point at that? Noticing that humans react to capitalism and the failures of market-based logic is a bit like saying “trees react to sunlight.” All trees do; it would be bizarre if they didn’t. These particular trees react differently though, and that’s interesting. They grow twisted branches and attempt to block out the sunlight of every other tree in a grasping, jealous rage. The differences, and those reasons, become important.

Incels have their own “market logic;” that is, they have their own economic explanation for the world and their behavior within it. The world is a cutthroat place of alphas and betas, and if you are born a beta male that’s too bad. This categorization of human beings into alphas and betas is unscientifically borrowed from the way wolves purportedly behave (and, as wolf-based imagery goes, is infinitely less creative and interesting than the wolf-based Omegaverse fanfiction community, with its knotting dicks and self-lubricating assholes). Much of what passes for theory among incels rests on pseudoscience recast as economic reality, or vice versa; in her book Culture Warlords, Talia Lavin gives an explanation of “hypergamy” as per a lonely white supremacist she was catfishing:

“[Hypergamy is the] instinctual desire of humans of the female sex to discard a current mate when the opportunity arises to latch onto a subsequent mate of higher status due to the hindbrain impetus to find a male with the best ability to provide for her OWN offspring (already spawned or yet-to-be-spawned) regardless of investments and commitments made to a current mate.”

If this all sounds scientifically questionable, that’s because it is. “Hypergamy” and “the hindbrain impetus” descend from the pseudoscience of evolutionary psychology, whose conclusions regularly validate the presumptions of capitalism, despite the fact that homo sapiens is hundreds of thousands of years old and capitalism is a 500 year old baby. Within the framework of capitalist realism, it makes sense to imagine that women are simply reproductive machines seeking to maximize their ROI: a gender of mechanical harpies whose primal instincts gear them toward perfect efficiency. But when you realize this atavistic, machine-precise image is just that—an image, an assumption, and a really nonsensical one at that—then it vanishes like a nightmare, and what you see instead are humans: you and her, and billions of others just like you, just the same mix of striving and mess and jokes and needs.

What’s in fact bitterly, brutally ironic about inceldom is that it relies on the same “sexual marketplace” logic that women have long been forced to accept—that men are hunting for the most beautiful available woman, meaning you won’t land a good one unless you’re thin but not too thin, pale but not too pale, and you better not develop dishpan hands or he’ll leave you. These days, young incels obsess over their jawlines, worrying that if they don’t hit some arbitrary beauty standard, they won’t ever be loved by shallow women on the prowl for the sexiest available man. As Lavin describes young men in the incel community who have sought out plastic surgery:

“They were working toward an idealized masculinity warped by misogyny so complete it isolated them from reality. A millimeter of bone, for them, was the way to punch a particular button in the inhuman, alien female psyche that would break down sexual resistance.”

Again, this is not really different from the way women have long been told they need to trick men into loving them. Until about five minutes ago in cultural terms, men were the ones who were considered animalistic and guided by their “hindbrains,” men who only cared about “one thing.” Whether it’s men or women (or both) who are re-imagined as mindless, ROI-seeking animals, the perception comes from the same set of capitalistic assumptions: that sex, like everything else, is a market, and you are in competition, and someone can only love you for your waist, or your jaw, so it had better be maximally optimized—“looksmaxxed,” in incel terms.

The idea that sex is a “marketplace” is quietly agreed on in a remarkable number of places. Jia Tolentino, in an otherwise terrific New Yorker piece about incels, says that in America, “sex has become a hyper-efficient and deregulated marketplace, and, like any hyper-efficient and deregulated marketplace, it often makes people feel very bad. Our newest sex technologies, such as Tinder and Grindr, are built to carefully match people by looks above all else. Sexual value continues to accrue to abled over disabled, cis over trans, thin over fat, tall over short, white over nonwhite, rich over poor.” In the New York Times, Ross Douthat locates the origin of this “hyper-efficient and deregulated marketplace” in everyone’s favorite foe, neoliberalism. He writes that “like other forms of neoliberal deregulation the sexual revolution created new winners and losers, new hierarchies to replace the old ones, privileging the beautiful and rich and socially adept in new ways and relegating others to new forms of loneliness and frustration.”

Of course, rich and beautiful and socially adept and straight and able-bodied and ethnically privileged people have always been pretty good at getting laid in societies that have favored those qualities (aka most of them); what’s changed isn’t “market deregulation” but something quite different. The sexual revolution of the 1960s predates the formal advent of neoliberal deregulation in the United States, and bears no relation to it whatsoever. Thanks to the sexual revolution, American women became less economically dependent on men, and therefore more free to choose sexual partners. It’s true that our culture still favors straight, white, cissexual bodies, but gay and queer and trans people are able to love now more openly than ever before. This doesn’t indicate “a deregulated market,” but a somewhat fairer one, in which everybody is closer to participating on equal terms.

But is sex even a market at all? The truest expression of neoliberalism is the belief that the entire sphere of human relations is naturally governed by market forces, the god that interpenetrates all. In this understanding, everything belongs to and can be explained by the market, and competition is zero-sum. This is what incels think is happening along every spectrum; that women are not only withholding sex in favor of a better market option, but also out-competing them in the workplace. A similar mindset can be found in racial anxieties, as Lavin discovered in her research. “The distance from the antifeminist ‘red pill’ [conviction that you have discovered some secret underlying unwoke truth about reality] to the racist ‘red pill’ was not so far,” she writes. “Each, in its own way, represented conspiratorial worldviews, in which the rights of women or minorities were a zero-sum game, promoted by sinister actors to deprive men and whites of their due.” The most common expressions of racism are a doubled fear of brown people taking away 1) white women and 2) white men’s jobs. It’s winner-take-all anxiety, the fear that if you (or the collective you, however imagined) can’t compete you will be replaced; in other words, the logic of the market distilled.

Market logic is part of why incels get so confused about sex—are women providing a good or a service, and if they are, then are they allowed to refuse sex, or is that like a restaurant refusing to seat someone? Again, this is the wrong set of questions. Sex is transactional because much of human life has been made transactional, thanks to capitalism and other oppressive systems before it. But sex—much like friendship, or family relations—does not, by any means, have to be transactional. The existence of sex work might seem to complicate the issue, but it really doesn’t, no more than than the existence of restaurants complicates home-cooked meals. It’s quite probable that the inequities that we see in both uncompensated domestic relationships and compensated sex work do not arise from some kind of “natural” transactional quality innate to human relationships, but from a lack of economic freedom, fairness, and respect.

What if human relationships ceased to be economic relationships? “I think a big part of the dream that many socialists have is to be released from having a life that is ruled by money,” writes my colleague Nathan J. Robinson. “The first priority, of course, is the abolition of class and making sure every person is free. But there is a certain dislike for exchange relationships generally. We want a world where you give someone something because you would like them to have it, not because you are looking to get something out of them.” As it stands, far too many people get into and stay in relationships for economic reasons. Thanks to the pandemic and concomitant recession, a staggering number of women have dropped out of the workforce due to layoffs or to take care of children; this, in turn, increases their dependence on their male partners, and makes it harder for them to leave or to have an equal say in their relationships. This is the 1950s, pre-sexual revolution model: sex as a condition of housing, marriage as a job. The dream is to liberate sex and relationships so that they are no longer fundamentally economic, to strip away the economic assumptions about reality that have fenced in our choices. This, incidentally, wouldn’t mean that sex work would disappear, any more than art or music. It simply means that none of those practices would be tied to the pursuit of making enough money in order to eat.

Is this dream the future that incels want? Based on their own words, I don’t think so. The phrase “TFW No GF” means “that feel when no girlfriend,” and the documentary explains it as a phrase “used to describe one’s greater fragile emotional state as a result of loneliness and alienation.” This is true to an extent—it is about loneliness and alienation—but again, it’s not just about loneliness and alienation. The phrase is still no gf, after all. A girlfriend is an acquisition, a demonstration of status. In the pseudoscientific/economic sensibility of inceldom, a girlfriend is proof that one has successfully outcompeted other men. As Tolentino explains, “Incels aren’t really looking for sex; they’re looking for absolute male supremacy. Sex, defined to them as dominion over female bodies, is just their preferred sort of proof.” Possession of a girlfriend is understood as a solution and an end; loneliness mixed up in the acquisition of objects, in which women are the highest prize. But “a girlfriend” is more than that, too; a woman in your life who loves you and will listen to you is the closest that many men will get to actual social support. As sociologist Jessica Calarco recently said in an interview with Anne Helen Petersen, “other countries have social safety nets. The U.S. has women.”

It would be unfair to hold incels solely responsible for their perception of women as prize objects or as ministering angels of sympathy. Capitalist realism, advertising, and centuries of patriarchy have insisted on these images, after all. “It is men, not women, who have shaped the contours of the incel predicament,” Tolentino writes. “It is male power, not female power, that has chained all of human society to the idea that women are decorative sexual objects, and that male worth is measured by how good-looking a woman they acquire.” This message is deeply cruel to men as well as women—if you’re unable to acquire a beautiful woman, if you’re not the protagonist of all reality, then does that mean you’re a failure? Are you genetically unacceptable and doomed to loneliness forever? What if you’re not talented, not special? What if you’re just…kind of a guy? What’s wrong with being kind of a guy, not better than anybody else, not superior, not inferior? Do you need to be superior to other people in order to matter?

If you can’t be the hero, you might as well be the villain. The villain is at least important and gets noticed; and if you can layer that up in Joker imagery, then it might even look like you appreciate this ironically and are in on the joke. In TFW No GF, the subjects are quick to explain that their frequent misogynist jokes are solely for attention. Charles, who has tweeted “I will shoot any woman at any time for any reason,” and “I’m not a misogynist I just hate women,” was questioned by local police for a gun-toting Joker meme. He insists he really doesn’t hate women at all; it’s just that misogynist or depressing statements simply do better and get more likes. Kyle says that “fucking misogyny on Twitter, it’s like anything else on twitter, fucking saying the n-word or anything else, it’s just funny because it is, it makes people mad. The people that get mad about tweets are fuckin r*tards, so it’s funny to make them mad.”

Posting a sexist or racist tweet “as a joke” and laughing when people “take it seriously” isn’t really funny, of course. But it’s not meant to be. As the guys admit, it’s solely about and for attention. It’s the equivalent of a preteen boy running up and hitting a girl with his backpack and running away again: HERE I AM, I EXIST. NOTICE ME. It’s a cry for help, and an assertion of power; getting to be the perpetrator rather than the victim, the one who hurts and upsets and confuses people rather than the one who is hurt, upset, confused. And while it may be born out of legitimate pain, it also rests on the presumption that the world is made up of perpetrators and victims, and some should be while others should not be, and you, who were promised everything by a society that was lying to you, are owed everything. You should be one of the somebodies; you should be seen.

Incel mass murderers aren’t, as the documentary suggests, an aberration, doofuses who take the joke too seriously. They’re the ultimate expression of the desire to exert power over others, to be famous, to frighten, to be noticed. The incel community may pretend to only ironically revere the mass-murdering Elliot Rodger and Alek Minassian as “saints,” but that’s because they’re too cowardly to admit they’re serious.

If, of course, you were indeed a lonely person, and you wanted love, you might not spend your whole day online trying to get a reaction out of people by upsetting them and then simultaneously bemoaning how lonely and depressed you are. Moyer’s incels may want to explain their behavior as simple causation—they are alienated by society, therefore mean jokes. But it’s a feedback loop—alienated, therefore mean jokes intended to display superiority and detachment, therefore more alienation from everyone else. Tfw no gf, and it’s partly your own fault, because you’re kind of an asshole.

Here we begin to get into difficult territory as leftists; to what extent do we consider unhappy, unsupported, underemployed people responsible for their own actions? Can we neatly slice apart “alienated because capitalism” from “acts like a jerk”? This is an old debate; as Robinson calls it “the ancient sociological question of ‘structure versus agency.’ Are our outcomes,” he asks, “determined by the social structure in which we find ourselves or by the choices made by us as free individual agents? This question can become extremely contentious, because the “all agency” perspective (anyone can pick themselves up by their bootstraps) seems a cruel lie that blames people for a failure to overcome impossibly unfair barriers, while the “all structure” perspective seems to treat people as pure victims with no agency.”

At the risk of sounding like a centrist, surely there is some middle ground here. Surely people are simultaneously deeply affected by the cruelties of capitalism, yet not helpless victims before it. The fact that incels might want to be perceived as social victims bereft of personal responsibility is really an abdication of agency. In one of the great ironies of all this, it’s a desire to be feminine in its most stereotyped sense; to give up the heroic protagonist role; be helpless, to be pitied and cosseted and cared for: to be treated like a woman. As Andrea Long Chu says in her wonderful book Females: “Everyone does their best to want power, because deep down, no one wants it at all,” and “to be female is, in every case, to become what someone else wants. At bottom, everyone is a sissy.”

This is another source of incels’ vaunted irony; they’re afraid to reveal their vulnerability. They want to be treated sympathetically, as they believe women are treated. (“I’m not implying that girls can’t be disaffected, obviously,” says Charles, “but it’s so much more prevalent in nerdy young boys to just be cast to the wayside, their feelings aren’t really that [considered].”) But of course these guys would be terrified to be actually treated like women, because they know how they would like to treat women.

In some ways, inceldom is a reaction to a certain oversimplified social justice discourse, the kind which foolishly imagines that basically every white man is handed a job and a car the minute they graduate high school. There are indeed sectors of the internet where pity is doled out based on suffering and identity categories; where you might get more automatic sympathy and cosetting if you are a woman and not a nerdy young cis white man. This attitude may be partly responsible for the recent wave of white academics who have faked being POC; there can be a kind of currency in suffering, if you have the means and shamelessness to leverage it. But the popular idea that Tumblr “created” the GamerGate and alt-right reaction—as if being irritated by stupid comments about identity written by teenagers is a reasonable motivation for sending death threats to women writers—is an example of the push-pull of victimhood and responsibility. “Social justice warriors are mean/annoying, therefore I was forced to double down on misogynist cruelty” doesn’t sit well with “it’s just a bit of harmless meanness, people shouldn’t take it so seriously.” Are you a helpless victim of capitalism, simply reacting naturally to other people’s bad ideas, or are you a person with agency, who is hurting people on purpose because you enjoy their pain? Are you the only one who is allowed to respond to terrible pressures in unjust ways?

Who is a “victim” and who is a “villain;” who is to be pitied and who is to be shamed forever—these are all political decisions, and moreover they’re also zero-sum decisions. It’s probably time to retire them entirely. But for that to work, we have to be willing to accept some basic realities: namely, that we are alienated but we still have agency; we are responsible for how we treat other people no matter how sad we are; and we are all in this together. In the documentary, Kantbot proudly claims, “You have to make the space you want in the world, it’s not going to be given to you.” This is of course, not news to many different types of people, and the mature reaction to finding out that this is true for you also, despite what you may initially have believed you had been promised, should probably not be to lash out in anger at the people who have always struggled to make the space they want in the world. You are not more deserving than others, and you never were. But you are also no less deserving. Incels are indeed victims of economic anxiety, they are lonely and they deserve love—just like everybody else.

In the truly fair marketplace of human desire (that is to say, not a marketplace at all), there’s always the chance that you might lose. Someone might not want to sleep with you for any number of reasons; someone you fall in love with might not love you back. The question for incels is whether they’re willing to accept this risk, or whether they’re still invested in the old model of capitalist immiseration as long as they end up on top. The limited peek provided by TFW No GF is not promising. Gabert-Doyon enthuses about a scene toward the end of the movie where Kyle describes an unpleasant overnight bus trip and, as Gabert-Doyon describes it, “[finds] communion with the passenger sitting next to him over how bad the bus trip is.” But that’s not quite what Kyle actually says. According to him, his seatmate said, “fuck, man, this fucking sucks, huh?” and Kyle replied, “Yeah man, but shit, we’re in it together. It’s like, fuck it, we’re all living it, try and enjoy it.” Meanwhile, Kantbot—banned from certain online mediums for his inflammatory posts—tells us that he’s decided to focus on his Patreon and his podcast. “Each tweet,” he tells us inanely, “is a moment of consciousness, and they’re all connected by your brand.” Sean, another of the documentary’s subjects, has started working out and getting attention from girls, but he says he doesn’t really want to date. He decries “grind culture” where you’re expected to “grind in your 20s and grind in your 30s and grind in your 40s and grind yourself to the bone, but it’s like there’s no character-building happening anywhere.” And yet, Sean’s solution is to embrace grind culture, keep lifting, and not seek out a girlfriend just yet, because “I don’t want to settle for something because I’m not even settling for myself, I feel like I’m always pushing myself. It’s like a full-time job to fight the effects of modernity and all the atrophy and stuff like that.” He’s aware that capitalist modernity is destroying him, and that the world is unfair, but he doesn’t think there’s much to be done about it. “It’s precisely because life isn’t a meritocracy,” he says, “that it just doesn’t faze me when someone has something that’s better than me. It doesn’t matter, it’s like, you can’t change it.”

The incels in TFW No GF don’t seem at all interested in trying to build a better world. Their conclusions are to find ways to enjoy the misery of capitalism, form friendships with like-minded dudes, focus on their careers and their workouts, and try to enjoy the physical world around them. “Normal, every-day stuff,” as one of them puts it. They don’t question the existence of capitalist hierarchy: initially, they’re mad that they don’t have a prime place in it, but by the end of the film they’ve accepted their diminished status. I can see how Gabert-Doyon came away impressed by the five subjects’ ability to “[analyze] their own cultural and socioeconomic identities”—all five of them do express a number of thoughtful, cogent insights. But just because someone is aware of the cruelty and inequity of capitalism doesn’t mean they’re opposed to it. This is one of the dangers of trying to find common ground with incels, and reactionaries in general: yes, they too have identified the problem, but they have their own answer, which is not the same as ours. Reactionaries may agree with us that capitalism is bad—Lavin notes in her book that “a persistent low-grade resentment of capitalism…pervaded the [white supremacist] chats” she was monitoring—but her subjects mostly blamed it on the Jews. The future that reactionaries long for (aka a nostalgic mostly imaginary past where men were men and lesser people knew their place) is not even close to what egalitarian socialists have in mind.

We do know that there’s a connection between material conditions and reactionary ideology; white supremacists thrive at times of massive economic anxiety, and it seems their incel cousins do as well. Would socialism save them? I think it’s unlikely that we’ll ever be rid of people like this entirely—that young men will stop dreaming into their adulthoods of being heroes, the coolest, the best, or that people will stop finding an elemental joy in hurting other people. Ultimately, socialism will not give anybody a girlfriend; it can’t hand women out as a nationalized good, because women are human beings and not a public utility. Socialism can’t make anybody likeable, or kind, or loved; socialism can’t get you laid. It’s not a shortcut. It may make certain things easier, by providing a milieu in which being kind and nurturing is socially rewarded rather than mocked and despised. In fact, it may bring about a sort of sexual revolution for men: in which, rather than having to regard every element of existence as a move in a zero-sum game for domination, it would become acceptable to simply have feelings, enjoy things, and pursue whatever makes you happy. But it will be impossible for socialism to ever free your life of all loneliness, romantic conflict, alienation, and unhappiness. You’ll still have to do all the hard work of being a person.

For what it’s worth, I think we should have sympathy for incels, as we should have sympathy for everyone who’s struggling, and try to provide them with warmth and community. But it’s actually quite cruel to tell people that nothing is within the scope of their responsibilities or their capabilities. It renders it impossible for them to build their character and commits them to a permanent adolescence, in which they are children who must be pitied, not adults who are responsible for how they treat other people. I’m sure Moyer has sincere compassion for her subjects in TFW No GF, but there’s a sly brutality in not being honest, in not telling the full story, in treating these guys as mere victims who can’t help lashing out because they’re sad. They’re smart and self-reflexive; they can be kind, if they want to. No one’s irredeemable, but they have to be willing to do the work, and people who are concerned about the fate of incels have to stop apologizing for them in advance, or demand for them a sympathy they refuse to extend to others.

These guys are unhappy, and their loneliness is pitiable. They have few options; this is a bleak and brutal country. But this is a bleak and brutal country for everyone, including the women that incels think they are owed sexual access to, and if they just tried to see those women as human beings like themselves, struggling like themselves, who are not a cure or a prize but just more lost and confused people, they might actually find the happiness they’re looking for. But to do that, they would have to give up their childish dreams of superiority once and for all.

There’s no socialism without solidarity, and TFW No GF shows that incels have solidarity—with guys like themselves, and no one else. They believe they’re owed something, something in particular, something more than other people, something that the universal solidarity of socialism won’t ever be able to give them. But it’s always possible for them to change their minds, and admit responsibility, and decide they’re ready for real solidarity and community instead. Right now they’re standing outside in the snow, looking on bitterly through the window at the light and life inside—but they can enter any time. The door is open. They just have to choose to come in.