Thomas Frank on Populism, Cool Brands, and the Problem With the Democratic Party

The author of “Listen, Liberal” and “What’s the Matter With Kansas?” shares his thoughts on the slow, ugly decline of the American empire.

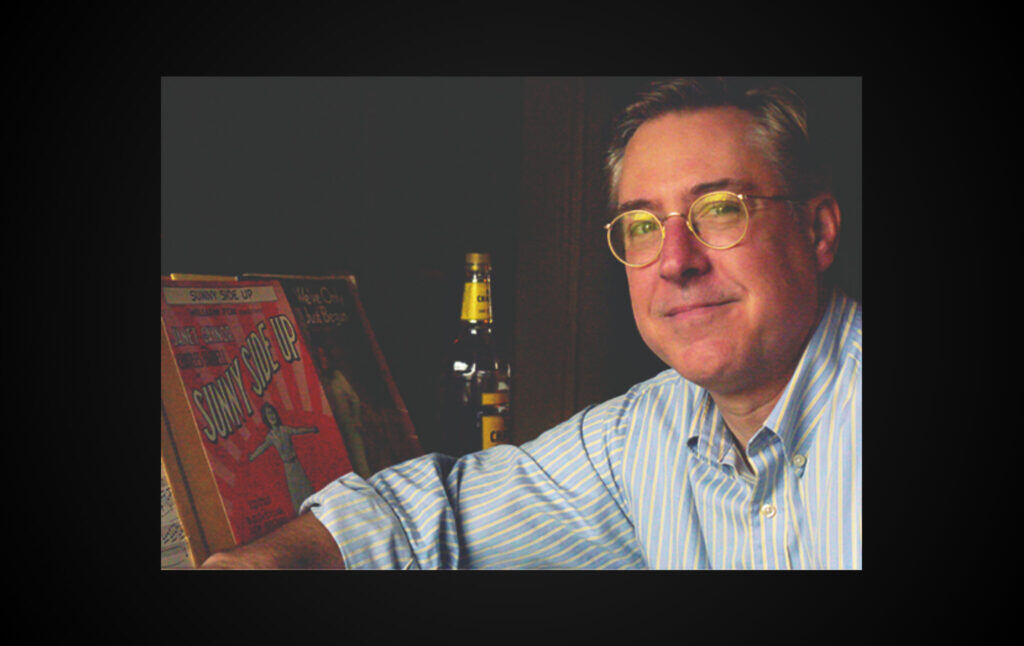

Thomas Frank is the founder of the Baffler and one of the most thoughtful authors currently walking this planet. He also may be one of the most cynical people alive. For decades, he’s been analyzing the devolution of U.S. society into a hellish muck pit of corporate greed and political corruption. The experience has left him deeply disillusioned, but it has also provided him with a treasure trove of fascinating stories—including covering the first Tea Party protests and boring Barack Obama at a cocktail party—which he shared during an interview on the Current Affairs podcast with editor-in-chief Nathan J. Robinson.

The following transcript of their conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Nathan J. Robinson

Good evening, Current Affairs listeners. My name is Nathan Robinson. I am the editor of Current Affairs magazine. I am here tonight with Thomas Frank. He is the author of a number of best-selling books on American politics and culture, including: What’s the Matter with Kansas?, The Wrecking Crew, most recently, Listen Liberal. Actually, it’s not the most recent. You’ve got one after that, haven’t you? Sorry.

Thomas Frank

I have a book of essays—

NJR

Book of essays, yeah. What’s that one called?

TF

NJR

You’re always so uplifting.

TF

Well, it’s Roosevelt’s famous phrase, “This generation has a rendezvous with destiny.” And I always loved that phrase. But I’ve been a cynic, and I always look on the dark side of things, the gloomy side, for as long as I can remember. And I’ve actually used that title before. I’m so drawn to it.

NJR

There’s so much I want to talk to you about your sort of pessimism. But let me just finish—I’ve got more to say about you.

So, in 1988, Thomas Frank cofounded and edited the Baffler, a magazine without which there would be no Current Affairs magazine. And I have long drawn inspiration from Dr. Frank’s work. Dr. Frank—

TF

Oh, stop.

NJR

Doctor?

TF

No one calls me that.

NJR

Nobody? You sure? It’s—

TF

Oh, it’s true. I have a PhD.

NJR

I can’t say Dr. Frank?

TF

Well, I don’t think anybody has ever called me that.

NJR

All right, what do you want?

TF

Tom.

NJR

But then you’re just a guy called Tom. I wanted to establish your credibility.

Anyway, so his work mixes political science, journalism, history, and is never dry and often deliciously scathing. One of the most clear-eyed analysts of capitalism and the culture it spawned. It’s a great privilege to get to talk to him today.

TF

Awesome.

NJR

So I was re-looking through Listen Liberal, and you mentioned pessimism. But here’s the crazy thing—

TF

You know why, Nathan? Because being utterly and completely pessimistic has served me very well.

NJR

Well! I know! Because I was going to say—

TF

It’s kind of uncanny, really—

NJR

Right!

TF

When you go back and look at it.

NJR

Because the thing about Cassandra that people don’t remember is that she was right. She was right about stuff. And the end of Listen Liberal here, which was published, what, April 2016?

TF

Right.

NJR

Yeah, right in the spring. I mean, on the last page here, you say, “The Democrats posture as the party of the people, even as they dedicate themselves ever more resolutely to serving and glorifying the professional class. They combine self-righteousness and class privilege in a way that Americans find stomach-turning. Every two years, they simply assume that being non-Republican is sufficient to tally the voters of the nation to their standard. This cannot go on.” That’s April 2016. November 2016—

TF

I think Trump is mentioned once.

NJR

Once. Yeah.

TF

Yeah. But that’s right. I just mentioned him in passing as an obvious blowhard. He was my example of an obvious blowhard.

But this goes way back. So I wrote a book called One Market Under God, and it was during the great stock market bubble of the 1990s. CNBC, the stock market channel, was new at the time. And I would have it on 24 hours a day, you know, while the bubble was ascending.

NJR

Why?

TF

Well, I had to get that sort of sense, that spirit into my writing. You know? I made a commitment. I would read management books and all this sort of thing. And I thought that was timely, because it came out right as the bubble was bursting, and I used to start… yeah, well, you don’t want to hear this, but I would go around the country talking about it and I would start lectures by reading about what had happened to IBM that day. What had happened to the different hot shares, the different hot stocks of the 1990s.

NJR

One of the cool things in your books is that you do have a kind of sick pleasure from diving into all of the texts of the right.

TF

Yeah, but I’m done with that now. I did that so much that I couldn’t… It just seemed pointless. I think after reading the eighth book by Glenn Beck—

NJR

I was going to say, I’ve got your book Pity the Billionaire and—

TF

Yeah. Yeah.

NJR

–read all of Glenn Beck’s output from 2008 to 2011, which is—

TF

I know, I know. I did it. And I also read books by Dinesh D’Souza—and I’ve got shelves of this crap. I read The Works of George Gilder. I used to do that. I don’t do that anymore. I’m working on a different thing now. I mean, I am reading right-wing publications, but from a different era.

NJR

I want to start with sort of talking about your Baffler days, because one interesting thing to me is that, I mean, you mentioned that you have been on-message for a very long time here. And you really have observed, from the beginning, the rise of market fundamentalism and the neoliberalization of the Democratic Party.

And it seems to me—I mean, I was alive in the 1990s, but I was too young to notice anything— like the Baffler of the ‘90s was one of the very few places that was screaming into the void about what was going on. And it made me imagine you spent the ‘90s like the play “Rhinoceros,” where everyone around you is slowly turning into this awful, Silicon Valley, jargon-spewing corporate person, and you’re like, “What is happening?”

Is that accurate?

TF

Wow. I don’t know what to say about that. I mean, in a certain sense, yes, it is.

So, I went to graduate school and studied history, American history. And after I did that, it seemed just incredibly obvious to me that the way you wanted to spend your career was writing for a general audience, not writing for a scholarly audience. You know, you could do real scholarship and do real digging and come up with real ideas. You do all that stuff. But writing for a general audience, that just seemed obviously preferable to me.

I don’t know if anybody agrees with that anymore. The contempt that you… I’m getting far away from your subject, from your question—

NJR

No, no, no, this is—

TF

I want to stick with it, but I have a tendency to digress.

NJR

Digress away.

TF

But the feeling that I get nowadays is that nobody wants to do that, or that they think that this is an impossible career choice.

NJR

Yeah. I’ll tell you, because I was in grad school at Harvard, and I’m still in it, technically, but I don’t show up really anymore. But—

TF

You’re in New Orleans.

NJR

I ran away to New Orleans. It was striking to me, though, that exactly what you say, there was this real kind of contempt for what is known disparagingly as “popular writing.” Like if our writing is popular, that’s a bad thing.

TF

People would say that, but we all knew deep in our hearts that, in fact, that was what you wanted to do. Right? To have people read your writing. And especially in American history. I mean, the greatest of the American historians—in our time, anyway, I’m thinking of Christopher Lasch and Richard Hofstadter’s…

Sorry, I’m older than you. But those guys wrote for a general audience, and they were widely read—or Arthur Schlesinger, any of these guys. And I wanted to do that. That’s what I wanted to do.

I’ve always been a huge fan of Edmund Wilson, H.L. Mencken. Mencken didn’t even go to college, you know. But people who wrote about serious ideas for a popular audience. That’s what I wanted to do. And that just feels like something that is no longer possible. Not because it’s less desirable, but because there’s just no way to support that kind of career anymore. I mean, you can do it as a hobby or something. But to actually do it and earn a living is incredibly tough.

But you were talking about the ‘90s. We were really sort of isolated from the world. For one thing, we were in the South Side of Chicago. We had an office, I lived in Hyde Park. I always tell people that Barack Obama was my state senator. So it was the neighborhood around the University of Chicago.

NJR

Did you know Adolph Reed? Was he there at the same time?

TF

I did. I did know him, yeah.

NJR

Because I just interviewed him and we talked about when he wrote this thing about Obama in 1996 that was like, “This guy’s someone.”

TF

Yeah. Isn’t that uncanny? Everybody knew that Obama was on the rise. You would see him at house parties in the neighborhood.

NJR

Whoa.

TF

Everybody loved that man. And that’s what people would say about him, always the same thing: “He is going to be president someday.” He was so sharp and he’s—I don’t know if you ever met him—he’s considerably taller than everybody else in the room. And he’s got that incredible smile. I thought he was pretty awesome.

NJR

He’s one of the most likeable people that has ever existed.

TF

It’s funny, in Listen Liberal, I was so critical of him. If we could have run him a third time, he would have easily won. No question about it. Anyhow, to get back to the subject of the Baffler.

Our office was down on 61st Street in what had been an old parking garage that we sort of fixed up, with a bunch of people who had their offices in the same building. There was a sense of isolation from the world, but also from Chicago. I don’t know if you’re familiar with the city, but that part of Chicago—or at least back then—it wasn’t even included on maps of the city when we went and bought a map. They didn’t even have the South Side. It wasn’t on there.

But I did love that place. You’d wander around the South Side, which had been deindustrialized in the ’70s and ‘80s. And all the steel mills had gone. It was a fascinating place to live. I really enjoyed it, and I miss it terribly. But there was definitely this sense that you were—there was this sense that you were apart from the rest of America, and even the rest of the Midwest and even the rest of the city.

NJR

So were there any precedents to the Baffler? I mean, were you drawing on any kind of inspiration from anything?

TF

Oh, absolutely. Most definitely. So if you go back and look at those issues from the ‘90s, they’re physically patterned after H.L. Mencken’s magazine—it was called the American Mercury in the ‘20s. So, in the ‘20s, he did some great things. It later became… it all became awful.

NJR

Didn’t it get bought by a white supremacist or something?

TF

Yeah. It had a really awful later history. Terrible things happened. But in the ‘20s, it was something else. It was really extraordinary. And at a garage sale or something like that, we bought a box of them from the ‘20s. Not the entire print run of it, but most of them.

What we would do is we would take a particularly 1920s timebound advertisement for telephones or something and we would cut it out, put our own words in the ad.

NJR

That’s funny. I, too, in the first issues of Current Affairs, because we couldn’t afford to have original illustrations and photography, I was cutting up old postcards from—

TF

Out of copyright, yes.

NJR

I was finding stuff that nobody would sue me over and using that as our art.

TF

Yeah. So you learned from us. Yeah.

NJR

But now we and the Baffler can afford original art.

TF

Yeah.

NJR

And so for years, you’re just sort of trying to build, I guess… if the only precedent is H.L. Mencken in the ‘20s and then you’re here—

TF

Oh, no, I had all sorts of other authors that I looked to, that I admired, and if you go back and look at those old issues, it was really obvious who we were fans of. Christopher Lasch loomed particularly large in our little intellectual world, a bunch of other people.

NJR

Why is that? A lot of people love Christopher Lasch, and I’ve never read him. Why does everyone love Christopher Lasch?

TF

Because he’s not an easy person to read. His sentences are excellent, but the essays are tough to get through. But he had a really original take on recent American history, that meaning from the ‘60s up until—when did he die, 1995 or something like that? He thought that a lot of the things that passed as liberation in fact were the very opposite.

You mentioned Mencken becoming a crank, and Lasch could be a crank, also. The thing is people like you and me, we’re experimenting with all sorts of new ideas and putting things together in unusual ways. That’s what we do. And there’s always the risk that you’re going to say something stupid.

You know, it’s funny—I’ve said a lot of stupid things in my life, and I’ve come up with a lot of stupid interpretations. And I’ve walked away from all sorts of dead ends. But I’m very happy with where I am right now, with where my ideas have taken me. I felt like with Listen Liberal that I got at something that had been annoying me for years that I couldn’t—you know, an itch that couldn’t scratch, you know?—but I finally got it.

NJR

Well, that’s—

TF

I finally nailed it. And so I’m very proud of that.

NJR

You founded the Baffler in ’88. So that’s four years before Bill Clinton comes along. And then you spend the ‘90s watching Clintonism become the Democratic consensus.

TF

Clinton made me very angry at the time. I remember the day welfare reform passed. It infuriated me. It infuriated me. Although now that I’m old, now I’m in my 50s, I don’t remember if it was welfare reform or if it was the crime bill… I’m pretty sure it was welfare reform. I just remember walking around the streets of Hyde Park, so angry at the liberal world that had been hoodwinked by this guy and that had allowed him to do this.

Because that was the really first big reversal of a New Deal program. I mean, they killed it. That was extraordinary. And it was so cruel. It was just mean.

NJR

Yes. Well… I wrote a book about Bill Clinton called Super Predator. The subtitle is “Bill Clinton’s Use and Abuse of Black America.”

TF

Oh, I did see it.

NJR

But the thing was that I started reading about Bill Clinton, and I felt just in so much rage that I had to write this thing. The fact that so many people bought into what he was saying, and I was like, “This is so obviously so cruel.” I remember when I was in college, it’s stunning how successful he was at convincing liberals that this was progressivism.

When I was in college, I remember a political scientist saying something like, “Well, we know welfare reform succeeded and we know it because look at how the welfare rolls dropped.”

TF

Yeah, because welfare doesn’t exist anymore.

NJR

And that was the measure of success.

TF

It doesn’t exist anymore.

NJR

People are on it. So it worked.

TF

The Washington Post still says stuff like that today. I have it in Listen Liberal. They were like, up until very recently, they were arguing that, because their hands are dirty in that, too. This was the center course. If you go back and read the kind of literature of Democratic centrism in the ‘80s and ‘90s, getting rid of welfare was—I mean, that was target number one. Getting NAFTA passed, what they called free trade, that was number two. And Clinton did it. He punched each item on the card.

NJR

Yes.

TF

It was infuriating. But it was also the logic that people would use to explain him away. It all was related to triangulation and that kind of thing.

But what’s funny is, Nathan, I remember that day, being so angry. Also, I was mad at Clinton’s telecom reform. I used to be in college radio. After college radio, while I was doing it, I met a lot of people who were in the radio industry in Chicago. And when they did telecom deregulation, it’s just like you could see it coming: they’re all going to lose their jobs. Because they were going to consolidate now, five stations would all be done by one guy sitting at a big board.

They basically overturned all of these anti-trust regulations on radio broadcasting. Radio broadcasting used to be a very local medium. And now it’s all, it just comes off the wire like everything else.

The same thing has happened to so many industries. I mean, look what’s happened to newspapers. Jesus Christ, look what’s happened to academia.

NJR

Right.

TF

But then George W. Bush comes along and the Iraq war and we forget all that stuff. And we stop being angry. And it all came back to me while I was doing the research for Listen Liberal, especially when I got to the part about the Crime Bill of ’94, which I had completely forgotten. And I had forgotten how culpable the Democrats were—specifically Bill Clinton—how culpable they were in mass incarceration, which is really one of the most evil things this country has done in my lifetime.

And it all came back to me. The way they tried to dodge it and deny their responsibility for it, it’s sick. But there’s that—you know, there’s NAFTA, bank deregulation. Each of these things was a world-class disaster.

And we look back at it as a successful presidency, like why?

NJR

Well, I mean, successful if you’re a Republican.

TF

Yeah.

NJR

Successful for pushing the kind of agenda that is favored by the people that you described in Listen Liberal, incredibly successful. Barack Obama is a successful president by this measure.

TF

I mean, they’ve never looked back, the wealthy in this country.

NJR

You also wrote a lot in the ‘90s, I understand, about not just free market policy but the way that neoliberalism kind of ate the culture and suffused everything. And this is the part where I imagine it felt like going insane, like in “Rhinoceros.”

It’s the idea that ate the world. It really is. It’s everyone and everything, and becomes this kind of religion. You called the book One Market Under God, and the stuff that you’re describing—and you describe, in Pity the Billionaire a lot, you describe the free market religion.

TF

Yes. And you’re in academia—it’s there, too, now, where the culture of management has taken over there. It’s everywhere you turn.

I mean, this is something that I don’t write about as much, but it’s always there. Wherever you scrape the surface, people have internalized market values. The whole cult of the Democratic Party is probably the worst example—and their alliance with Silicon Valley and with Wall Street, with Big Pharma. The ideas of the market place essentially are everywhere. The ideas of competition and innovation and entrepreneurship are everywhere. Inescapable.

NJR

I try to train myself now to notice when there are kind of hidden neoliberal assumptions. I find it’s easy to accept premises accidentally.

The most recent example was I was reading a liberal critic of a conservative argument about education. And the conservative argument was, “The education system doesn’t prepare people for jobs. High school is worthless for creating human capital. Sociology programs, they’re worthless.” And the liberal defense was, “No, no, no, no, no. There’s—

TF

Wait, wait, wait, let me guess. Can I guess?

NJR

Yes, please.

TF

“So we have all these examples of people who studied English and look at how much money they make.”

NJR

Correct.

TF

Yes, I’ve heard this argument.

NJR

“No, it is economically useful.”

TF

Nobody can actually defend it on its own terms.

NJR

Right. So, regarding the internalization of market values: I read recently about the Obama administration’s “Race to the Top” program, because I was fascinated by it. I mean, I didn’t pay any attention to it at the time. But then I looked back on it, and started to understand how it worked. And I was horrified, because “Race to the Top” was a program that gave states money for education if they had met a series of criteria, performance criteria, and one of the criteria was—

TF

Oh, oh, oh, oh, can I guess? Is it—

NJR

Uh-huh.

TF

—is it charter schools?

NJR

It’s charter schools. And the thing is, giving money to the schools that do well instead of the schools that do poorly is such a fucked philosophy. The left philosophy is: you look at the people who need things and you give it to those people. Not: you further exacerbate inequality by rewarding the people who do well.

TF

Yeah. You’re right, sir. It is massively frustrating. Can I tell you what I’m working on right now?

NJR

Please.

TF

By the way, we should talk at some point about the commodification of dissent, which was I thought, when you are talking about market values, that felt like our signature idea back in the 1990s.

NJR

And you wrote a book. Right?

TF

Yeah, Commodify Your Dissent was the title of our Baffler anthology. It was something of an obsessive idea for me back then. It’s odd that I got my way into politics. I sort of backed into politics accidentally, almost. I started by writing about what I thought was the ultimate commodification of dissent: the advertising industry in the 1960s.

NJR

The coopting of counterculture values.

TF

Yeah. That’s right. Yep. Yep. The conquest of cool.

NJR

You had the Orwell ad.

TF

Exactly. Yeah. And that’s in some ways the most atrocious example of it, and also one of the most celebrated TV commercials of all time. I forget who the agency was now. But I was writing about that, and I was writing about the advertising industry. And then I went to write about the current bubble—the bull market of the time in the late 1990s—when all of these theories of how capitalism worked were coming out, were being brought out into the open and being used to explain the world around us.

I used to read the Wall Street Journal religiously back in those days. That’s where I got started, reading the other side, right?

NJR

Oh, I tell everyone to read the Wall Street Journal.

TF

And I still remember the sense of shock that I felt when I signed up for a subscription and the first one came, and I opened it on my kitchen table in Chicago and I was like, “What? What are they saying?” And this is the op-ed page, where I later was a columnist. This was the heyday of the bull market of the 1990s, and they were trotting out the most amazing theories to explain what was going on.

I was hooked instantly. You know? Instantly they are just like, “Look at this crazy stuff that a huge, important part of American society believe.” The stuff that people who are making the decisions, the life and death decisions over all of us, believe. It’s like reading the astrology column or something–it’s that ridiculous. And I couldn’t turn back then.

That led to politics almost sort of by accident. But my study of business culture led me into politics. And now I can’t get out, Nathan Robinson. Now I’m stuck. Now they won’t let me leave.

NJR

You’ve said a lot. There’s so much I want to comment on. But first, just a fun fact: the agency that did the 1984 ad for–

TF

Was it Wieden+Kennedy?

NJR

No, it’s Chiat/Day or something. But anyway, they’re in the Theranos book, Bad Blood, because Elizabeth Holmes hired them to make Theranos ads.

TF

Oh, no.

NJR

Anyway can you just define for the listeners what you meant by the phrase “commodify your dissent?”

TF

This was shocking and new at the time, the idea that being a rebel was a pose that you purchased. It was something that was defined by products that you bought. So in other words, rebellion had been folded into consumerism. And then you take it one step further. Politics was going to get folded into consumerism.

And I don’t just mean by that that you’re wearing a T-shirt with Che Guevara’s face on it. I mean that brands would start to identify themselves with causes, and brands would recast themselves as social movements. And this was starting in the 1990s. I mean, the pre-history of it is the “conquest of cool,” that stuff in the ‘60s. But it was becoming more obvious in the ‘90s.

Now, it’s in your face every minute. I mean, Nike, Nathan Robinson, is so much more radical than you could ever hope to be.

NJR

It’s true.

TF

Do you know what I’m referring to?

NJR

Uh…

TF

The American flag tennis shoe?

NJR

Yeah. Of course. Nike’s woke.

TF

Oh, hell, woke as shit, man.

NJR

Yeah. Nike gets it.

TF

They’re way ahead of you.

NJR

They’re really…

TF

What I used to say back in the ‘90s was that the day is quickly approaching—I was a little punk rocker back then—and I would say, “The day is quickly approaching when Madison Avenue is going to be cooler than any of you,” speaking to my friends. “Cooler than any of you can ever hope to be.”

The advertising industry is going to be cooler than you—and there’s no way to stop them because they’re better organized, they have better research, they’re so much better at this game than we are.

But it’s worse than that now. Madison Avenue, Nathan, is going to be a better leftist than you will ever be.

NJR

Yeah.

TF

They’re going to be more woke than you.

NJR

To take it into politics a little bit—when we were talking about the coopting of people of dissent and of people’s discontent, in Pity the Billionaire, you talk interestingly about the way that organized capital took popular rage and funneled it into—

TF

The Tea Party.

NJR

Until you framed it like this, I didn’t think about it this way. But it is kind of incredible that they took what should have been this sort of popular rage at capitalism and went, “No, actually, what you love is big business and what you hate is the government,” and then there are all these grifters, all these right-wing grifters—

TF

No, they were there on day one.

NJR

—who were making a fortune—

TF

They were, yes.

NJR

–off people’s anger.

TF

It’s the ultimate commodification of dissent. In some ways, it’s the ultimate example because of the consequences that it had for us. The fact is that we never got a proper New Deal after the financial crisis. We never got a proper recovery effort or a proper Works Progress Administration or proper bank regulation. None of that stuff happened. And it’s largely thanks to the Republican cleverness.

Now look, they knew, to put this in marketing terms, they knew that their brand—the Republican Party brand—was hopelessly tarnished by George W. Bush and the Iraq war, and all the other screwups of that era. And he was, remember, deeply unpopular when he left Washington. There had been all of these scandals, the Abramoff stuff, the Iraq war, Hurricane Katrina. Then there’s a financial crisis on top of all that, and the economy explodes. And he’s like, “See ya. Bye.”

It was the exact perfect moment for a Franklin Roosevelt type of figure—everybody sensed it, everybody was talking about it. TIME Magazine had that picture on the cover with Obama’s face and the famous image of Roosevelt.

And what does the Republican Party do? Now, these guys are very canny players. Whatever else you want to say about them, they are very, very, very good at the game of politics. They said, “Let’s recreate our brand as something else,” and they used this name, this deliberately confusing name, the Tea Party. And I’m still, to this day, I meet foreigners who are like, “Is that a real political party or what is that?”

The Republicans immediately started holding rallies in parks. It was months into the Obama administration. By the way, one of my very few things that I have to brag about in my journalistic career is that I was at the very first Tea Party rally. I wrote about it in the Wall Street Journal the next day, and I made fun of them. I thought it was so ridiculous.

As you know, I’m obsessed with the 1930s. And so, I had told all my friends, “Sooner or later, you’re going to start seeing big public protests about this stuff. Can you guys tell me when you find out about one?” And somebody emailed me, they’re like, “There’s one tomorrow, and it’s downtown in D.C., Lafayette Park,” and I went there and it was a Tea Party.

It was a bunch of guys from K Street, lobbyists—in suits, right, on their lunch hour. It was a lot of guys from Grover Norquist’s outfit, a lot of guys from whatever Newt Gingrich’s group was, a lot of guys from Dick Armey’s group. And it was so clearly a put-on. So I made fun of it the next day in the paper.

And I’ll be damned, the Tea Party caught on. It turned into what I said earlier, the greatest commodification of dissent ever because they convinced a huge part of the American public that they represented the real hard times protest movement. And they did this deliberately. They embraced this kind of confusing language, this vague language deliberately, like the whole image of the Boston Tea Party, of course.

NJR

Right.

TF

They also used all kinds of 1930s imagery.

NJR

Yeah.

TF

Anyhow, one of the most interesting things, since you asked about Pity the Billionaire, is where I—and this is the last time I was going to read, I thought, I was ever going to read right-wing literature—I read all of Atlas Shrugged.

NJR

Oh, my.

TF

Have you ever read this?

NJR

I have never managed to make it through all of Atlas Shrugged.

TF

And I developed a theory of Atlas Shrugged.

NJR

Okay.

TF

So, it’s not a book to read before you go to bed. Let me put it that way.

NJR

Unless it makes you go to sleep.

TF

You will have incredible nightmares because it’s all about the strong triumphing over the weak. Put in a hundred different ways, and then expressed in a hundred different other ways, and on and on.

NJR

Because even the National Review, when it came out, said, “This sounds like it wants to send people to the gas chambers.”

TF

Yeah. What is it, “Get thee to a gas chamber.”

NJR

Yeah.

TF

And then the review is by Whitaker Chambers. Do you remember that?

Speaking of all that, my theory of that book is that it is the story of the Great Depression reimagined. Okay? It’s all of these incidents and recognizable characters from the 1930s, only instead of having been caused by a stock market crash, a credit bubble, and all the things that went into causing the Great Depression, they’re all caused by government interference in the economy.

And she takes well-known incidents in history and changes them from being disasters of the corporate world, the private sector, to being disasters brought on by government—the most famous being this train crash that’s the central episode in the book. Because I’m reading the book and there’s this train crash and it happens in this tunnel, and she describes the tunnel very, how would you put it, concretely. “This is how long it was. It was the biggest tunnel through the mountains,” blah, blah, “It had this system for ventilating it, but the system wasn’t working.”

And I’m reading this and I’m like, “This must be based on a real incident.” I found the incident.

NJR

Oh.

TF

Yes. It’s one of the biggest loss of lives in a train accident of all time. It happened in Washington state. It was in 1910 or something. And anyhow, you can read all about it in Pity the Billionaire. But it was also famous because it was one of the first big negligence lawsuits. The surviving passengers tried to sue the railroad because the railroad had made all sorts of incredible mistakes, and put them in harm’s way. And then they got killed in an avalanche, is what happened. They were up in a snowstorm in the mountains.

It’s a long story. But anyhow, a huge negligence lawsuit. And Ayn Rand flipped the script and makes it into, you know, “Big government ordered them to do this terrible thing and all these people died.”

NJR

You know, I like the existence of Ayn Rand in many ways because she’s so honest, right? She also kind of shows what happens when you act like this type of person in that she dies alone and miserable and alienates everyone around her and is obsessed with her own rationality. And it’s just really a lesson in why you shouldn’t be Ayn Rand.

I also like that my fantasy and her fantasy are the same thing, which is that all the CEOs fuck off to the mountains.

TF

Colorado. By the way, and that’s based on a movie, too. It’s based on a movie from that period. Now what the hell movie am I thinking of? Lost Horizon. Have you ever seen Lost Horizon?

NJR

Oh, is this a Frank Capra?

TF

Yeah, it’s Frank Capra. But it’s not in Colorado. It’s in the Himalayas.

NJR

Mm-hmm. I have seen that.

TF

Yeah, yeah, yeah. Anyhow. Not a movie. It was a novel. And then a movie. I shouldn’t have said big government causes the train crash. It’s a liberal politician who threatens to have his buddies in big government… It’s liberals and big government, all intertwined.

So, Ayn Rand is, in my opinion, not a great writer, with one exception. It’s an important exception, and that’s when she is describing machines.

NJR

Right.

TF

She’s excellent—

NJR

Not good with people.

TF

Not really people, no. Her people are stilted. It’s like Dickensian characters: you can guess how everything’s going to turn out for them just from their name alone—like does it have a certain consonant cluster in it, you know? But when she’s describing machines, like train engines, she’s great. There’s this machine that the guy builds—what is it? It’s like a perpetual motion machine of some kind, a dynamo. Her descriptions are fantastic.

NJR

Yeah.

TF

They’re beautiful.

NJR

Well…

TF

She really had a skill for that.

NJR

No wonder the Silicon Valley guys all love her.

TF

Yeah, there you go. Like, ugh.

NJR

Ugh. So, when the Tea Party—just to get back to the Tea Party— I think it’s fascinating. Everything from Santelli’s rant at the beginning, where he sounds, if you’re not listening to his words—as if it’s an anti-Wall Street rant. But it’s a defense of Wall Street—

TF

Yes.

NJR

–against poor people who lost their houses.

TF

Yes, exactly. Exactly. And he delivered it on the floor of the Chicago Board of Trade. I love that detail because I used to study populism, uppercase “P” populism, you know, the real deal. And for them, the Chicago Board of Trade was the focus of evil in the world. And now you have a populist movement that is called into being from the floor of this spot.

NJR

So, I just interviewed Arlie Hochschild this morning and I was reading Strangers in Their Own Land, and she talked to all these Tea Party people. You really see this crazy thing happening where they’re all like, “Well, you know, the market is delivering us these wonderful things. The oil companies are doing this thing.” Meanwhile, they’re getting poisoned.

TF

Isn’t that shocking? I read that book. That anecdote—or, not anecdote, it’s like half the book—is just, it blows your mind. You know, that kind of thing happens in America every day. It’s all over the place.

NJR

And one of the Tea Party guys she talked to is a real environmental activist, because he’s seen his bayou destroyed, and then he still goes like, “Oh, I’m a big free market guy,” and votes for Bobby Jindal.

TF

Yep. Well, it’s the only utopia in town, isn’t it? It’s the only sort of vision that anybody has of a future of prosperity and—not really equality, but freedom, anyways.

NJR

Well, that’s why I like… I mean, I think people should read Pity the Billionaire and Listen Liberal together, because they really are like the two halves of the story.

TF

You touched on something important here, which is the failure of liberals to offer a narrative, to use an overused term, a competing narrative. And it’s not like they don’t have one. It’s not like they couldn’t come up with one. They just don’t want to. It’s out there. We all know what it is.

NJR

Right.

TF

I’m writing a book about the ‘30s right now, and I’m reading this stuff every day. It’s not hard to look this stuff up. You just go down to the library and pull the works of Henry Wallace off the shelf or something. And there it is. And they don’t use that. It’s a weapon that they refuse to bring out.

NJR

I used to think, “Well, you know, they’re so incompetent. Why don’t they just tell the left’s story, which is a powerful story which can appeal to people?”

TF

Especially in a time like 2008. Oh, my God.

NJR

Yeah. But, the thing that you point out in Listen Liberal is that they’re never going to tell that story because the “they” that we’re talking about are not people who want to disturb the existing economic order. There’s a quote from this big Democratic Party donor, Stephen Cloobeck, who is the CEO of Diamond Hotels, where he says, “I tell Pelosi if you say the word ‘billionaires,’ I’m never donating again.”

TF

Yep. It’s shocking and there are hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of examples of that kind of thing. You know, the maladies that afflict the Democratic Party… Look, I only just scratched the surface with Listen Liberal. What I’m proud of with that book is that I got the big picture right in a way that I don’t think anybody else had done yet which was to connect what was wrong with the Democratic Party to the kind of—how would you put it—the maladies of professionalism, the beliefs and the errors that are the follies of this particular social class, the things that they believe as a class are all…

You know, lots of people have pointed out that professionals have moved over to the Democratic Party. But that’s not a new observation. But the thing is, to understand the Democratic Party as an expression of their sort of class understanding of the world, boom, everything falls into place. All of a sudden, the Democratic Party makes sense. I’m proud of that.

NJR

And that’s why you went to Martha’s Vineyard.

TF

Yes. Yes. That’s where they come together. That’s where you can see them in all their glory, and they’re hidden from the rest of the world as an island, you know. It’s hard to get to.

NJR

They literally all live on a secret rich-person island.

TF

Only in the summertime. They all vacation there. I didn’t know anything about it, by the way. I’d never been there before. I grew up in Kansas City. I’d never heard of it when I was a child.

NJR

I thought it was a vineyard for so long.

TF

Yeah. It turns out it’s not.

NJR

What was it like?

TF

Oh, come on. You lived there. Boston, right?

NJR

I never went to Martha’s Vineyard, my God.

TF

There’s lots of beautiful gingerbread houses and lots of seafood. And yachts. There’s yachts everywhere. There’s private beaches. I had never seen that before. I’m not a big beach person. I’m from Kansas City. But they have private beaches there with a fence around them that you can’t get on them.

NJR

Did you see Alan Dershowitz on the porch at the general store or whatever?

TF

I didn’t see anybody famous.

NJR

Okay.

TF

All the restaurants and stores we went to all had photographs in the windows or on the walls of either the Clinton family or the Obama family. Both of them vacation there. And I wonder if the Biden family, once he gets into 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, if he’s going to start vacationing there, as well.

NJR

There were a number of things that made me think Barack Obama, definitely not a secret leftist, because a lot of people go, “Oh, well, he’s operating with political constraints but really he’s more progressive.” But there were small things that make you go, “Yeah, I don’t know. People who summer on Martha’s Vineyard, they’re a particular type of person.” You could go anywhere. You’re the president. You could go anywhere.

And now, like now what Barack Obama does is he hangs out with Bono.

TF

Bono. Now there’s a guy to write about, you know.

NJR

And you’ve chosen Bono. That says everything. That says all I need to know about you.

TF

I know. I know. I know. It’s awful. I never really thought that Obama was a secret progressive. I did think that his hand would be forced by events.

You know, just as with Franklin Roosevelt—Roosevelt had good instincts. He had excellent political instincts, and he tried out all sorts of different ideas before he found what worked. They sort of stumbled into Keynesianism. When he ran for president the first time, he was still planning to balance the budget. He was promising. And eventually he discovered that the magic thing, the real ticket, was to do the exact opposite, deficit spending. It took him a while to figure that out, but they did.

I thought that events would move Obama in a similar way. What was fascinating to me was how hard he struggled and how clever he was to avoid doing what history was shoving him to do, to avoid doing what all the signs were telling him to do. And you see this not only in the way he dealt with Wall Street but in Obamacare, which is needlessly complicated. It’s massively complicated for one purpose and one purpose only, and that is to preserve the primary insurance industry. You know?

NJR

He said, “Oh, we don’t want single payer.”

TF

All these incredible workarounds, the thing with a million moving pieces, just for that.

NJR

He has this crazy quote where he says, “People talk about single payer, but what about the millions of jobs that we lost in the private insurance industry?”

TF

I know. I know.

NJR

You’re admitting they’re useless.

TF

Can you imagine Franklin Roosevelt saying that? Well, maybe you can. I don’t know.

But all the things that he did to preserve Wall Street from any kind of blowback or harm, it is extraordinary what he did. All of his brilliance and all of his ingenuity and all of the tough guy, Rahm Emanuel stuff that he had at his disposal, was used in the opposite direction. And that is fascinating.

NJR

I remember my stomach churning when Obama announced his cabinet picks. And I was like, “Oh, dear.” All of the excitement, all of the promise, just suddenly disappeared. You were like, “These people are not the people that you would get.”

TF

Yeah.

NJR

You have a crazy quote from—that I’d never seen—from Larry Summers in Listen Liberal, which is like, “One of the reasons inequality has probably gone up is that people are being treated closer to the way they’re supposed to be treated.”

TF

He didn’t say that to me. He said that in one of the books about Obama. Confidence Men, the Ron Suskind book.

NJR

Disgusting.

TF

Yeah. But there’s many quotes in that book. Confidence Men was a huge bestseller, Nathan, so you have no excuse for not reading it. But there’s a lot of stuff that I dug out of the archives in that book that I’m proud of. There’s a guy from the Carter administration who says it would make him happy if the Teamsters were worse off. Did you see that one?

NJR

No.

TF

Yeah. And so, an economist from the Carter administration talking about how good it would be if organized labor got its ass kicked, basically. And that is actually then what happened.

NJR

Yes. You got your wish. Now we have Trump. Well done.

TF

Yeah. Thanks, guys.

NJR

Well done.

TF

They can’t put those pieces together. My faith in Obama persisted until, and I remember the exact moment that I lost it, and it was when I heard the words, “Grand bargain.” I knew instantly what he was up to, and I knew that it was his version of triangulation. And it was just like, “Oh…” I suddenly got the whole thing.

Because Obama, there were always two sides to him. He could do this brilliant analysis of what was wrong with us, which he did on the campaign trail in ’08 several times with what had gone wrong on Wall Street. He clearly understood, was much better informed than McCain, much better informed than George W. Bush. You know, that sort of thing.

And then he had this other side, where he bowed down at the shrine of bipartisanship. And I always assumed that that second part, the bipartisanship part, that that was just something that you said to make people in D.C. happy.

NJR

Yeah. No one believes that shit.

TF

Exactly. Only a sucker takes that seriously. I mean, if you go back, way back, I wrote a book called The Wrecking Crew about the right and how they built the machinery of the right in Washington, D.C., and I read Tom DeLay’s memoir for that—again, reading these unbelievable right-wing books.

And Tom DeLay says, “Every time Bill Clinton talked about bipartisanship and splitting the differences and triangulation, we’re like, ‘Well, let’s”—this is not a direct quote, of course, I don’t have the book in front of me—but he would say, like, “We just constantly move the goalposts to the right, because we knew that he would then try to compromise with us, and we’d move them again, ‘Look, now it’s over here! You’ve got to move a little bit further!’”

And they just played him. They played him. So, you’d think that by the time Obama comes along, it would be well-known that that’s a losing strategy. You know? This has been worked out. We’ve understood this. And no. Once I heard that term “grand bargain,” I understood immediately that that was real for him, the bipartisanship stuff, the Washington Post editorial stuff. That was real to him. All of this other stuff, who runs America, how does America run, how does the business world—

NJR

He’s the least cynical man in the world.

TF

And I’m the most. We met in person one time at a party in Hyde Park in Chicago.

NJR

Oh, my God. Did you put him off with your bitterness?

TF

No, no. But I don’t really remember what he said to me at the time. But, you know, he pretended to be interested in whatever I was saying.

NJR

One of the best parts of Listen Liberal is you have what I think is the kind of definitive reputation of the Democrats’ “Well, their hands are just tied,” argument, because you say, “Okay, let’s consider that argument. Why don’t we look at blue states? Why don’t we look at what happens in blue states and see, in a place where your hands aren’t tied, what you do? And then we can test the thesis of whether this is a compromise out of political necessity or whether this is ideological commitment?” And you look at Massachusetts and you look at New York, and you go, “Oh, it turns out…”

TF

Exactly. I like the way that you laid that out step by step very logically there, Nathan Robinson. That argument came to frustrate me so much in the later years of the Obama presidency. You actually had big league pundits here in Washington, D.C. saying that the presidency was not a powerful office, all to excuse their hero having feet of clay, right?

NJR

Yeah.

TF

“The office itself doesn’t really have any power, you know.” It’s like, look at Trump. Look at what happened.

And so, when this was all going on, I decided I would call around to all of my sources that I usually went to and asked them, “What could Obama do?” At this point he didn’t control either the House or the Senate. “What could he do anyway?” And I came up with a whole list of things that he could do toward the end of 2015 and they would have all been massively popular.

For example, prosecute these Wall Street guys. The suits were just never brought. You know, get off your butt and do it. It wouldn’t be that hard. Go after universities for the tuition spiral. You have all sorts of power over universities via the Department of Education, but you’re constantly forcing them to do this and do that. You know, crack down on them.

NJR

They go, “Oh, we couldn’t make out a case. We couldn’t make out a case against them.” You know, you’re a prosecutor. That has never stopped a prosecutor before.

TF

The one that still drives me crazy is antitrust enforcement. This is entirely in the hands of the executive and the attorney general. Entirely, 100 percent. All Obama had to do would be to say, “You know, Google, you’ve pissed me off one time too many. Here we go. I’m turning Eric Holder lose on you.” But he never did it.

And it was entirely up to him. Anyhow, all of those things would have been massively popular, and he chose not to do any of them.

For example, he could have dealt with the banks. He didn’t really need an act of Congress. You look at how Roosevelt dealt with the banks. He used his bail-out authority over them. They bailed out the banks back then, too. Obama did it all over again. He said seats on their boards. He could have walked into the C-suite, and said, “Bye. You’re all fired.” He didn’t even do that. He did fire the CEO of General Motors, but we didn’t go nearly far enough.

NJR

Right.

TF

Maybe his donations would have fallen off or something like that. But the country would have been 100 percent behind him. Okay, more like 80 percent. Still, people would have adored him, had he gotten tough with those guys.

NJR

But the important thing I think that comes out in Listen Liberal is that this isn’t just Barack Obama’s personal failing of cowardice.

TF

Right.

NJR

This is a symptom of a professional class mentality. So you’re going to get this from Andrew Cuomo, too. You would have gotten it from Hillary. You’ll probably get it from a Biden presidency.

TF

Al Gore. You would have got it from John Kerry. Any of these guys, Michael Dukakis. The one exception I’d say is maybe, in the last 30 years, is maybe Walter Mondale would have been different. But all the rest of them are basically the same.

NJR

Yeah. And at the state level, look at governments like Deval Patrick’s government in Massachusetts, and I think Deval Patrick was so in bed with the consulting and Wall Street that he couldn’t even run for president because he would just be too horrendously unpopular.

TF

Oh, can you imagine? It would be a bloodbath. He worked for Bane. I’m sorry, I’ve forgotten now the details about his career, but yeah, needless to say, he was fascinating. In some ways, Patrick was another perfect example of a really brilliant overachieving, really highly achieving guy. Was he a Harvard guy?

NJR

Oh, yeah.

TF

MIT? I forget.

NJR

Of course.

TF

Some Ivy League somewhere, you know.

NJR

Yeah.

TF

Did amazing favors for the financial industry.

NJR

Well, I don’t want to take any more of your time. I really appreciate you talking to me, and usually I like to end on an upbeat note, but I think that would be a disservice to your work.

TF

That would be a strange thing to do. Do you want to know what I’m working on now?

NJR

Yeah, let’s hear it.

TF

Populism. The real deal. The real deal. And also on anti-populism, which is in some ways even more fascinating. Why people hate populism, from 1896 to the present.

NJR

Isn’t that crazy? The Center of American Progress collaborated with the American Enterprises and I think they paid them a pile of money to do a joint study on the dangers of populism.

TF

I know. So I’m extremely partial to populism because I’m from Kansas and that’s one of the places where it caught on in a big way. And they took over the state and they did all these things. And every time I hear some European commentator describe some local racist as a populist, I’m like, “What the hell are you talking about?” You’ve got it completely upside down. They’re on the other side of that.

TF

I read an article that called Netanyahu a populist. You know?

NJR

Do you think Huey Long gets a bad rap? Because I do.

TF

Yes, but I’m not going into that in this particular book.

NJR

Okay.

TF

If you go back and read the things that he did that were so massively offensive to the Democratic sensibilities of the day, a lot of them are things that are utterly commonplace now.

For example, one of the things that really bothered people is that he always traveled with a bodyguard, with a bunch of bodyguards.

NJR

Which, you know…

TF

Completely commonplace.

NJR

Probably should’ve had more.

TF

Yeah, he ran the Louisiana state government like a dictator in the sense that he just sat there and was like, “Okay, pass this, pass this, pass this,” and the committee would be like, “All right.” And somebody would say, “I disagree,” and then they’d vote and it would be like eight to one, you know, always. That kind of stuff happens all the time.

So, in the ‘30s, never did they apply the P-word to Long, did they call him a populist. They didn’t use that word back then for people like him. The word was still specific—it meant a movement in the 1890s. But I do have a book about him from the period where they call him a forerunner of fascism. And it’s very interesting. The author sits there and watches Huey Long in action, but he finally says that Huey Long is not a Hitler type. He’s more just a guy who turned out to be extremely good at American machine politics. Just like absolutely a genius of it, you know? He just figured out how it worked, knew how to play it. And got everything done.

But if you read his books, they weren’t big, evil ideas. It was just, “I’m going to get this passed, and then I’m going to get that passed. I’m going to build a bridge.”

NJR

Bridge is still up. It’s a good bridge.

TF

Yeah. Exactly. So, in other words, he was—according to this way of looking at him—just a kind of really glorified or magnified version of a very familiar American type.

There was a great biography of him in the ‘70s, Harry Williams was the author. That’s really worth reading. But he did come out of a populist background. I mean, the real thing.

NJR

Well, I’m just impressed by the strength of the redistribution rhetoric.

TF

You know, it was extremely popular back then.

NJR

“Share our wealth.” That’s a great platform.

TF

And he had a way of explaining it that was very powerful. He’d go on the radio nationally and people loved that man. It’s kind of strange when you look back on it. I mean, Roosevelt arguably was just as talented in his own way, and of course got more done nationally.

NJR

Roosevelt wasn’t a threat ultimately to the rich in the way that—

TF

They certainly thought he was, though. If you go back and read what they said about him in 1936…

NJR

They couldn’t understand he had their best interest at heart. He didn’t want them to be murdered.

TF

That’s right. It’s like he was the only thing standing between them and the pitchforks.

NJR

I know. No gratitude.

TF

They hated that man. They hated that man. They thought he was a communist.

NJR

I wanted to ask you one more thing: did you ever regret calling the book What’s the Matter With Kansas? Because of the misinterpretation that it gets? I have heard people refer to that book as if you are the kind of liberal snob going, “Oh, what’s wrong with all these Kansas people?,” which is not at all what you were going for.

TF

I don’t regret calling the book that because it’s a good title. It’s provocative.

And by the way, so William Alan White’s famous editorial with that title, I first encountered it when I was studying populism as an undergrad, and I was like, “Damn.” Have you ever read it? You can find it online. You can pull it up. If you knew who the characters are, he’s referring to all of these different populists in Kansas.

And it was written in a fit of anger. He was really mad. Something had happened to him, like they had insulted him on the street or something like that. Some populists had been mean to him. And he sat down and wrote this incredibly powerful editorial, and it got picked up and reprinted all over America.

I’ve always been fascinated by him and by that title. And so, I’m not sorry that I used the title. I’m also not sorry for the way that I set up the question, which is, “Here are working class people voting for figures like Sam Brownback, who does not have their best interest at heart.” I’m not sorry that I set it up that way, because that is the question of our times, if you ask me.

We still don’t have a good answer. I mean, I supplied an answer again and again and again, but it’s like, you know…

NJR

Yeah, well, that was the thing with-

TF

Nobody gives a shit, right? Nobody’s listening. But I’m pleased at that. What I’m sorry is that a lot of people never got beyond the title.

NJR

Right. Yeah. That’s what I’m saying.

TF

My daughter and I have a joke about it, because it has happened to me so many times when my kids are there. People who are like, “You know, I haven’t read your book, but I have read the title, and I just want to say I have some strong opinions about the title.”

NJR

See, that’s why I asked you this question, because I expected that.

TF

Yeah.

NJR

Okay.

TF

So, it’s kind of a joke in our family. But, yeah, I mean, that’s classic, the people who read the first page or something and don’t read to the end.

NJR

Yeah.

TF

But it’s a good problem to be having.

NJR

No, it’s true. Right? You get talked about.

TF

But it’s also then they get the incredible surprise of learning that I also wrote a book called Listen Liberal. They’re like, “What?”

NJR

Well, a lot of people don’t understand that leftists exist, I think? Like Facebook used to have the option, like the political orientation, it was like, “Conservative, Very Conservative, Liberal, or Very Liberal.”

TF

Yeah, yeah. That’s right.

NJR

“Excuse me. Excuse me.” They’re like, “Oh, you’re to the left. You’re very liberal.” Thank you very much but no.

Well, Dr. Frank, thank you so much for talking to me. That was super fun. And I think everyone who wants to understand anything about the failures of the Democratic Party needs to pick up Listen Liberal, and about the way that the right has coopted the sins and created phony populism, needs to pick up 2012’s Pity the Billionaire. Still relevant. I would recommend that, too, to literally everybody.

Thank you so much.

TF

That was very kind of you, sir, and it was great to talk to you.