Satanic Panics and the Death of Mythos

Being alive has perhaps never been more confusing, especially because we have lost the tool that might help us make sense of it all.

A while back, I read a book called Dangerous Games: What the Moral Panic Over Role-Playing Games Says About Play, Religion, and Imagined Worlds by one Joseph P. Laycock. The book covers, in extensive detail, the creation and rise in popularity of Dungeons & Dragons and other role-playing games in the 1970s and 1980s, and the subsequent backlash against them led by the religious right in America, who viewed the players of such games as participants in Satanism. I’m actually not a fan of tabletop games—I have the nerdy disposition for it, but not the patience—but I will read anything about the Satanic Panic that’s put in front of me, and I enjoyed the book a lot. More importantly, there was one line in the book that stuck with me; not even a pivotal line, for that matter, more of an aside than anything, but an observation that I have thought about countless times ever since.

The book quotes Karen Armstrong, a writer on comparative religion, on the difference between what the Greeks called mythos and logos. Logos is, roughly speaking, knowledge gained through the world of science, reason and observation, through which we can understand the material world and the things in it, the laws of cause and effect in our environment, and how to navigate the more literal aspects of our world. We know, for example, that if we are feeling hungry, it is because of certain chemical processes in our brain and our digestive system, signalling that our bodies are in need of physical sustenance, and that if we eat, the chemical processes will stop and the hungry feeling will go away. We know that if we drop some of the food while eating, gravity will cause it to fall into our laps. On the other hand, mythos has been described by Armstrong as having to do with “the more elusive aspects of human experience”: all of that which cannot quite be explained in terms of the literal, mundane, or rational. It covers stories of supernatural events and experiences—the actions of a god or gods, if you like—which are not literally true by the standards of logos, but are meaningfully true in some other sense: psychologically, emotionally, spiritually.

So how did mythos and logos explain evangelical Christians’ hatred of spooky monster games? According to Armstrong, fundamentalist forms of religion—such as the schools of Christianity that dominated the Reagan years—collapsed these two worlds of understanding into one. One might think that mythos was the preferred realm of evangelicals, since they believe so strongly in God. But no—it’s logos that they love, and mythos they have no use for. For example, other schools of Christianity could understand Genesis as truth without it being literally true; God could have handed down to mortals a story about the Earth’s creation that imparted some kind of divine meaning, without negating everything logos told us about evolution and cosmology. But to fundamentalists, the Bible being true meant the Earth must have been made in seven days, because the Bible is the Word of God and every word of it is true, and true means materially and logically and scientifically true. The laws of our mundane world had to be the laws through which God was seen, too. Every piece of proof that the Earth was older than 6,000 years old which had been found through logos had to be “debunked” in the world of logos, or at least an imitation of it; hence the building of the Creation Museum in Petersburg, Kentucky, the arguments about whether or not dinosaurs were in the Garden of Eden, the attempts to explain the dimensions of Noah’s Ark and exactly how a pair of every animal on Earth managed to fit in there. (This also goes some way towards explaining the prosperity gospel, the belief that material wealth is proof of God’s favor and flows towards the righteous—after all, money is how we value things in the material world, so why not in the next world, too? What other measure of value could there be?)

Laycock, the author of Dangerous Games, draws on Armstrong to explain why fundamentalist evangelicals were frightened and suspicious of Dungeons & Dragons, along with any other form of art that played heavily on supernatural themes and gathered an intensely invested fanbase (such as heavy metal music). Since all things magical and mythical had to be interpreted in literal terms, they could not understand why people would feel so drawn into alternative worlds and be so fascinated by talk of summoning spells and pentagrams unless they were actually talking about summoning literal demons, the actual demons with the horns and everything. This belief was bolstered by a few tragic cases of suicides by teenagers with interests in these types of artforms, a shamefully reductive understanding of what had happened to these young people. Of course, people with all kinds of interests suffer from mental health issues, and deal with difficult circumstances that drive them to take their own life. It was too complicated for many to imagine that games might have been an escape for them, or dark music a way of hearing and expressing truths they already felt.

In fundamentalist forms of religion, the stories from the sacred texts are true, and anyone else’s form of mythos is at best nonsense that should be forbidden, and at worst an existential threat to the real truth. But anthropologists and sociologists have long pointed out that belief and action inspired by mythos are not only entirely compatible with the world of logos, but provide multiple important social functions. (Please note that while Armstrong tends to use mythos in a narrower sense, to refer more specifically to pre-modern mythologies, I will be using the term in a broader sense, to refer to all non-literal or non-rational parts of our understanding of what is true: rituals, customs, superstition, storytelling, art, and transcendent experiences.) In her seminal 1966 book Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, Mary Douglas describes how societies around the world have historically built their own concepts of the “clean” and “unclean” alongside myths and rituals which maintain and enforce social boundaries. They do this not necessarily out of ignorance of how things “really” work, but because these concepts fill the margins between what can be literally accounted for and therefore fully controlled. The book also explains how rituals and symbolism give meaning and order, help us mentally find a place for complex or murky concepts, give direction when we are unsure of what to do, and provide comfort after death and tragedy. Sometimes it can be as big as partaking in a ritual that feels powerful and utterly transformative; sometimes it can be as small as helping you pick out what kind of breakfast you should eat when you’re hoping for a good day.

If you are reading this thinking you’re not really a mythos kind of person—because you are not religious and have never had a supernatural experience—you are incorrect. Do you support a sports team, and do you feel ecstatic when “we” (the players you have never met or played with) win? Do you have an old shirt you should really throw out, but you refuse to do so because it feels “special” in some way? Do you feel people should treat you especially nicely on your birthday? Do you avoid stepping on the cracks in the sidewalk? Have you ever been moved by a piece of art in a way that can’t be put into words? Do you get excited when you find an unusually large potato chip? Have you ever stopped on a perfectly ordinary street, in the rain, looked at the ordinary houses or a certain whorl of tree-bark, and thought “my god, the world is here, and it really is alive”?

Not only do we need mythos to help us find these moments of deeper meaning, we need mythos to give shape to the total mess that is our lives. If you look back on your own life, you probably mentally separate it into different phases, considering certain moments to be “turning points” or classifying some phases as happier or more miserable. Realistically, our lives tend to turn from happy to sad to neutral in periods of hours or days, not in overarching seasons, yet we tend to think of our lives in terms of constructs of different sizes: our childhood, adolescence and young adulthood; spring when we clean, New Year when we go to the gym, and fall when we drink pumpkin spice lattes (even if we live in climates where the seasons don’t actually feel clear-cut). As Douglas puts it in Purity and Danger:

There are some things we cannot experience without ritual. Events which come in regular sequences acquire a meaning from relation with others in the sequence. Without the full sequence individual elements become lost, imperceivable. For example, the days of the week, with their regular succession, names and distinctiveness: apart from their practical value in identifying the divisions of time, they each have meaning as part of a pattern. Each day has its own significance and if there are habits which establish the identity of a particular day, those regular observances have the effect of ritual.

We need these kinds of rituals and segmentations so we can understand our own life as more than just a jumble of events. People generally do not have the power to remember every single day with its events and its moods and transitory thoughts, and if we did, it might make it more difficult to tease out the greater meaning of our lives, not less. In the short story by Borges, Funes el memorioso (“Funes The Memory Man”), a man wakes up from an accident with the ability to remember everything he has ever encountered in microscopic detail. Rather than elucidate things, his ability becomes a massive hindrance to his life, because he loses all ability to see the forest for the trees. When he tries to think of “a flower,” he cannot—he can only think of every individual constituent part of every individual flower he has ever seen. It is not the near-infinite facts of our lives which grant us meaning, but the larger patterns, the ideas, the rituals, the feelings. Without wider ideas, patterns, and symbols beyond the individual items we see in front of us, we have no way to understand what is important and why; we cannot fully think, and we are lost.

While Armstrong is by no means the only person to identify different categories of truth, and the strength of her categorization has been debated by classicists, I was struck by her ideas more than anything else in Laycock’s book. Indeed, in the years since I have been thinking about mythos and logos in relation to all sorts of shit; it has become a lens through which everything suddenly appears to me in a new light. It helps to explain the Satanic Panic, yes, but this rejection of mythos didn’t die with the 1980s. In fact, the denial of mythos is everywhere in our culture, and it can partially explain why so much of our approach to everything artistic, challenging, or mysterious seems reductive, dull, and unimaginative. It also offers an explanation for why, when evangelical Christianity came under heavy criticism in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the critics themselves formed a culture (the so-called “New Atheism”) that now seems unbearably trite, revelling in arrogant nitpickery and skilled only in missing the point. While the New Atheists’ concerns about the influence of religion in government might have seemed refreshing to many in the 2000s (including myself and, I’d wager, many of the readers of this magazine), in retrospect, the worldview they espouse now seems incomplete—not false, necessarily, but simply unequipped to deal with the more complex and unanswerable questions about our world, leading many to the conclusion that two-dimensional appeals to “science” and “reason” are not enough to create a deep and satisfactory knowledge of our universe. Think of Richard Dawkins berating Mehdi Hasan for believing Muhammad ascended to heaven on a winged horse, and unable to do anything but sputter “oh, come on!” in response to the idea that yes, a highly educated man could believe in miracles, or Neil deGrasse Tyson’s complaints about the inaccuracy of descriptions of the moon in the lyrics of love songs.

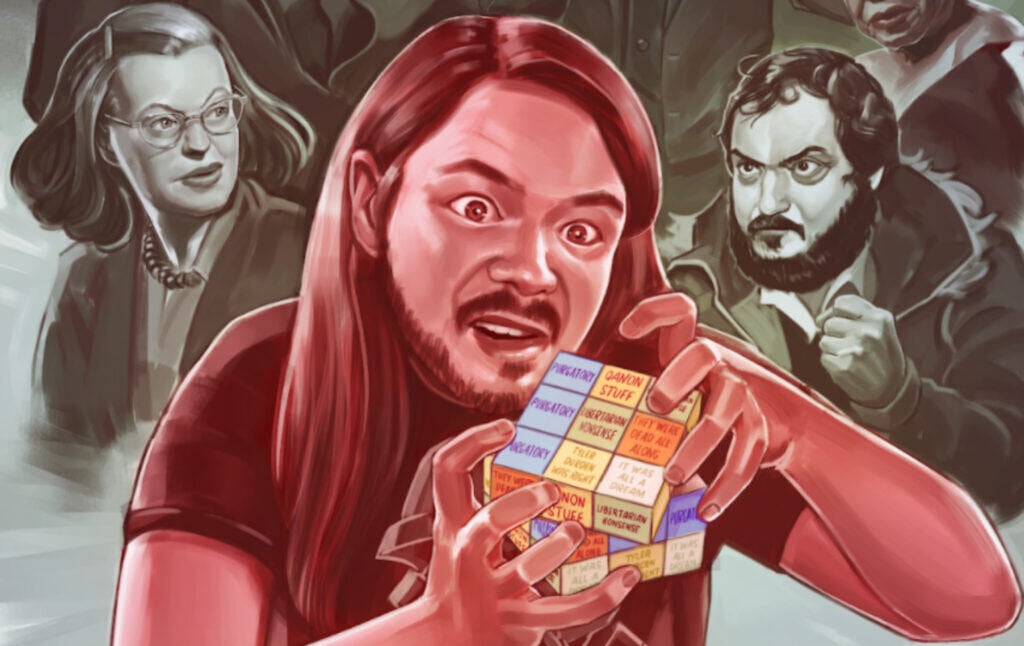

This rejection of imagery, symbolism, or any higher meaning that cannot be reduced to the literal, has become especially pervasive in contemporary art criticism.This is not to say that there isn’t still great art criticism; it’s just that the internet has led to a much greater volume of all criticism, and much of it is dominated by a worldview that seems to reject metaphor, symbolism, mood and tone, or at least render them secondary to “plot.” (By “plot” here I mean “the literal events that happen to the characters and no more,” ignoring the possibility that other aspects of the creation can comprise essential parts of our understanding). One of the most popular genres of movie “criticism” on the internet right now is the “ending EXPLAINED” video, where any ambiguity or multiplicity of meaning you felt at the end of the film you’ve just seen can be cleared away like spilled popcorn. How did Jack Nicholson get into that old photograph at the end of The Shining? Is Travis Bickle dead at the end of Taxi Driver? Is Deckard a replicant? Surely these are the discussions such movies are supposed to raise, and if enough nerds puzzle over screenshots for enough time, the definitive answer will be found and the movie will be solved.

The video essayist Dan Olson made a video for his Youtube channel, Folding Ideas, called “Annihilation and Decoding Metaphor,” expressing his frustration at this complete refusal to countenance the themes of a film as an integral part of its meaning (although he is far from the first or only person to comment on this troubling trend). In particular, he looks at Annihilation, a horror film with strong and unsubtle themes exploring how people are changed by trauma, which also happens to be the subject of endless “Annihilation EXPLAINED!” type videos. Says Olson:

The reason I dislike these [videos] so much is that they are often a form of anti-intellectualism operating on the attitude that ignorance is purity; that an understanding of culture that rejects metaphor, that rejects the symbolic and clings to the literal is more true. It is part of the process of denying art the capacity for meaning.[…]It is rare to find someone who will entirely reject the idea of approaching film broadly from a thematic or metaphorical point of view, but all too common to find people who will lightly sneer at the actual attempts to do so, and suggest that it’s overthinking things…This is a consistent feature within modern film criticism which, taken on the whole, is in a distinct phase where the loudest voices in film discussion are incurious, proudly ignorant, and approach plot as a problem to be unpacked and solved.

As Olson notes, this is not to say that no-one who makes these “explainer” videos is completely unfamiliar with the concept of metaphors. It is more that metaphors are considered more of a secondary matter or bonus feature—an extra level one can consider if one is “into that sort of thing”—but not something that may displace the “real” truth, the primary truth, of whether the spooky alien dies at the end or not. An earlier video of Olson’s, “The Thermian Argument,” excoriated the tendency of genre fans to excuse problematic content by referencing justifications from the lore, as if the fictional worlds they loved were literally real and not the deliberate constructions of an author with intentions. (“No, it’s not weird that the house elves are slaves! The books explain that they like being slaves!”)

These two video essays target slightly different phenomena, but phenomena which are manifestations of the same root problem: by getting bogged down in the literal objects, characters, and rules that populate the world—the “lore,” the “canon”—the fan loses sight of why the author chose to populate the world that way in the first place. All of this creation, real as it may feel to an enthusiastic audience, was the product of ideas that are worthy of discussion. The literal-minded fans are Funes the memory man, able to identify every Star Wars character and their backstory in perfect detail, with no ability to step back and ask themselves why a story about rebelling against an empire makes people feel so good, and whether they should think about that next time they put forth an opinion on Black Lives Matter.

Not only that, but if someone tried to connect the two within their earshot, this sort of fan might be dismissive or even indignant. The Star Wars characters live in another universe, where Black Lives Matter does not exist. They can’t “symbolize” or draw comparisons with anything in our world because they’re not of our world. It’s almost as if the fans believe they are actual people, and not artistic creations within a larger history of creation. Just as evangelicals imagined D&D players picking up the cards and going into the literal world of wizards and monsters, when certain kinds of fans consume entertainment, they see themselves as entering the literal world of their favorite franchise, learning more and more “facts” about the world, and the only thing that problematizes its existence is when the “reality” breaks—for example with an inconsistency in the lore. (Apart from “ending EXPLAINED” videos, one of the most popular kinds of movie-related videos on Youtube is the “everything wrong with” video, where a person blithely points out every “plot hole” they can find in a popular movie, no matter how small or irrelevant.) Not only is this a reductive way to understand individual stories, but it leads to a bleaker artistic landscape. The executives who commission new media know that this obsession with filling in the details of stories is popular, and easier to present to an audience than something new and risky, which is why almost no big movies are brand-new creations any more, but every popular media property now has a sequel, a prequel, and a Netflix spinoff where you can see your favorite character’s “origin story.”

To be clear, there is nothing wrong with geeking out over details, or pondering the minutiae of a fictional world. The issue is when the details are all an audience can see, at the expense of everything else that makes art meaningful. One of the most captivating art projects to come out of the past five years is a Youtube series called Petscop, which went viral in 2017 and held the attention of its fanbase until it ended in late 2019, despite frequent months-long gaps between the videos. Petscop is a creative project to which it is impossible to do justice in the written form, but I’ll try. It consists of 24 videos, each showing a clip from a fictional videogame called “Petscop,” sometimes narrated by a mysterious player named “Paul.” Petscop at first seems to be an innocent ’90s-era Playstation game about catching various creatures, but soon begins to turn strange, making enigmatic references to dark and traumatic subjects, and forcing Paul to wander the ominous landscapes of the game, puzzling out meaning from eldritch symbols, and confronting troubles that seem to relate to events in his own life, or the lives of people he knows.

If a story about an evil videogame sounds a little goofy to you, that’s unsurprising, as Petscop was clearly inspired by the oft-goofy “creepypasta” genre of internet-era horror stories, which often feature such things. However, Petscop elevates the trope of the haunted videogame into something much more complex and terrifying. Without ever having a jumpscare, it slowly builds a near-unbearable dread, not through telling you what is going to happen, but merely through tone, aesthetics, and blood-curdling implications. It also undoubtedly conveys thematic meaning, and on very difficult subjects, exploring childhood abuse, trauma, and memory through a highly complex, non-linear storyline that refuses to give any easy answers. (And how could there be any easy answers, given such a subject?) Rather than ending with a neat wrapup of the highly cryptic plot, Petscop appeared, enveloped its audience in fear and confusion, then quietly announced its conclusion, deliberately denying its viewers a simple resolution and leaving them with an unsettling experience rife with unspoken and multiplicitous meanings. I cannot describe for certain what happens in it at all, and it is one of the most phenomenal experiences I’ve had with art in some time.

As soon as the creator confirmed the series had finished, scores of fans seethed in rage and disappointment, mad that there was no “explanation” of what it all meant. They felt their time had been wasted: people had written entire documents on the windmill time-travel theory, the hypnotism theory, the rebirthing theory, whichever theory would take the enthralling, upsetting, utterly profound experience they’d had with the series and break it down into a series of coherent plot points. Many called the sudden ending a copout, declaring the creator must have just got stuck or messed up somewhere. If there were no clear answers, then as a series it was useless; if it didn’t have a sensible plot, with a character doing things and experiencing events in a literal, coherent order, it couldn’t possibly have any meaning. Many Petscop fans are young, and it is possible that this short-sightedness is just a matter of inexperience with difficult media. Nonetheless, I wish I could pin this message to their Reddit threads: the parts you can’t explain? That’s where the art is.

All the stories in humanity’s history that have had a lasting impact on us, from the Bible to Greek myths to the X-Men franchise, have been rich in meaning beyond the literal words and events they offered us. Whether it’s striking the right emotional note, enveloping us in a fantasy world, making us reflect on our own lives, inviting a search for meaning, provoking discussion, or giving us experiences we can’t explain, the role of art has always been so much more than laying out a linear “plot” complete with all the mundane details of exactly how character X got to location Y in a way that feels “realistic.” The undercurrent of excessive literalism and obsession with story mechanics that plagues modern fandoms and criticism is pernicious, and it denies us the tools we need to find meaning in art. To understand art, we need mythos—which means we need mythos to live.