Knowledge Is Not Power: Why Cigarettes Still Appeal

For many, the chance to reject neoliberal self-care culture outweighs the obvious health risks.

Cigarettes differ from most commodities in two important ways. First, they cause cancer. It is worth noting that the use of the word “cause” in this last sentence was made possible by the invention of meta-analysis in statistics and epidemiology that the scientific pursuit of the carcinogenic effects of cigarette smoking spurred. Second, as a result of decades of litigation over their deadliness, we happen to know more about the inner workings of the corporations that produce cigarettes than we do about any other capitalist industry. We have internal records revealing exactly what the companies knew and when they knew it.

Its critics are fond of calling the tobacco giants “rogue” corporations. But there is nothing surprising or out of the ordinary about their methods or their excesses. Yes, they publicly denied and actively obscured the harmfulness of their product. They marketed to kids. They paid scientists to create fake controversies. But this was not because they were uniquely malevolent. It was because they were ordinary corporations that meticulously maximized their profits. All of their behavior was simply what a “responsible” corporation would do in trying to serve its shareholders. That tobacco companies are responsible for a massive, global public health crisis is a result of the lethal force of their product in combination with the very typical practices of capitalist firms, which includes an indifference to “incidental” considerations unless they hamper or bolster profits.

The cigarette thus provides a privileged window to the world of profit-making. The history of the cigarette is as horrifying as Jim Mouth’s eyes while breaking his own world record for most cigarettes smoked at the same time. It is a maddening and revolting tale that brings grimaces and shivers alike. But what is most disturbing is the generalizability of its lessons: this is not the story of an exception but of a rule.

Tobacco came to Europe in the 17th century, around the same time as coffee, tea, chocolate, and other new exotica, and as with these other new pleasure goods, people took it in the form of “drink.” They were in reality smoking it, but the term “smoking” wouldn’t appear until later on in the 17th century. Until then Europeans had to get along with the awkward phrases “drinking smoke” and “drinking tobacco.”

The preferred vehicle of tobacco consumption then was the pipe, which would be supplanted in the early 19th century by the cigar, in turn overcome by the cigarette in the later 19th. Two technical developments paved the way for the dominance of the cigarette: first, the invention of “flue curing,” or drying tobacco at higher temperatures, which produced a golden yellow leaf with much milder smoke. Before flue curing, tobacco was air dried, and its smoke was typically too harsh to be inhaled. After flue curing, tobacco had to be inhaled to get the same nicotine satisfaction, and inhalation is the difference between a recreational activity and an addiction. As Gary Cross and Robert Proctor explain, “the shift from air-cured to flue-cured tobacco was something like the shift from opium to heroin or from eating to injecting drugs by means of a hypodermic needle: a new form of ‘consumption’ based on a new and intensified form of packaged delivery.” It was curiously in being made more mild that tobacco became lethal.

The second innovation was the mechanization of cigarette production: before the 1880s, cigarettes were all rolled by hand, typically at a rate of five a minute. Though many sought ways to speed up production, it was James Albert Bonsack who invented the machine that would revolutionize cigarette production in 1881. Bonsack’s machine, which could churn out 20,000 cigarettes in 10 hours, was obtained on an exclusive contract by James B. Duke’s American Tobacco Company. With technological superiority ATC dominated global production until 1911, when it was broken up into four companies by the exercise of the Sherman Antitrust Act. These four firms—ATC, Liggett & Myers, R.J. Reynolds, P. Lorillard—along with Philip Morris, formed the oligopoly that would oversee the 20th-century boom in cigarette smoking.

They would be aided in their efforts by World War I: not only did wartime seriousness mute the comparatively more trivial concerns of anti-tobacco advocates (still not yet armed with scientific proof), but cigarettes were an easily “realizable desire” at a time when desires were not easily realized. Soldiers returning home after the war further found their new habit perfectly suited to routinized labor time. Whatever you think of them, cigars are an experience, not something you fit in between shifts. Cigarettes, by contrast, are an anywhere, anytime pleasure, something that can be done now to break up the monotony of the day. In the 1920s and ’30s, the cigarette “was frequently cited as respite and solace in an increasingly bureaucratized and industrialized world.” Though no one would make this glowing claim today, the uncomfortable truth is that there’s still nothing quite like the cigarette—save for its recently-developed electronic versions. The appeal and persistence of smoking is a function of capitalist alienation as much as it is the addictiveness of the nicotine molecule.

If the rhythms of capitalist society offered the soil for the rapid growth of cigarette consumption, and flue-curing and mechanization fashioned the seed, it was the nascent advertising industry that provided the fertilizer. Advertising was not simply used to sell cigarettes: thanks to unprecedented spending on advertising in proportion to overall expenditures and a willingness to push the boundaries of propriety and truth alike, the tobacco industry created modern advertising.

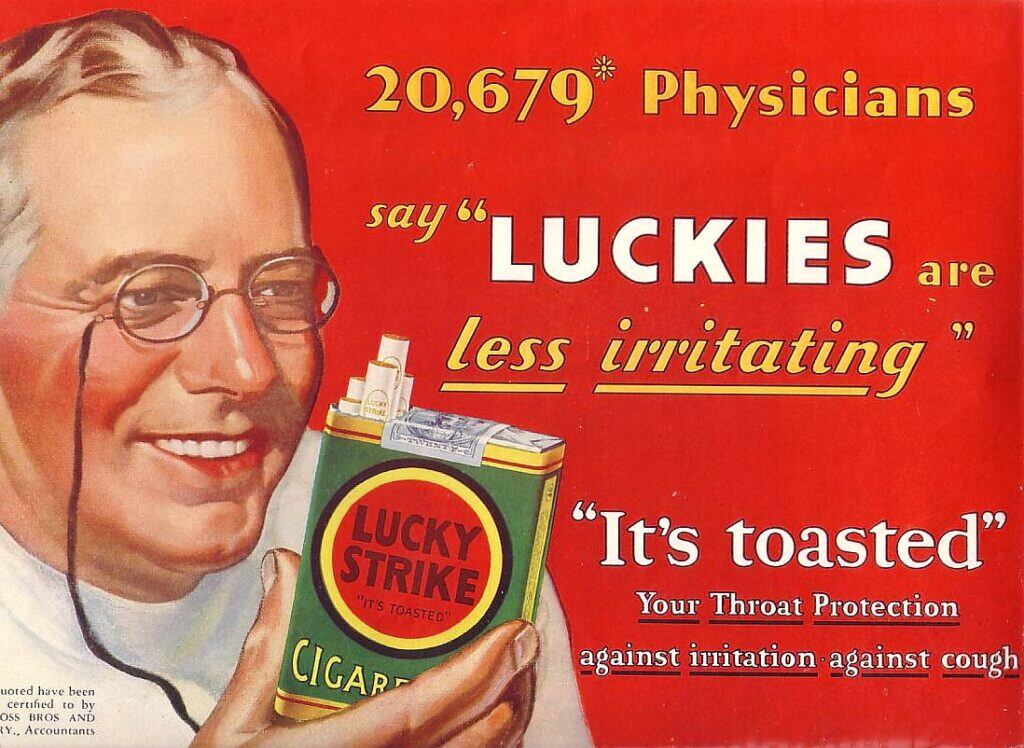

What is most remarkable about the “allure” meticulously shaped by cigarette advertising in the crucial interwar period was its fungibility. Cigarettes were masculine if you wanted to be manly, feminine if you wanted to be womanly, a virtual medicine if you wanted to be healthy, and a mysterious danger if you wanted to throw caution to the wind. Sometimes agencies didn’t even mind pursuing contradictory strategies: for instance, while touting the various health-promoting features of smoking (soothing the nerves, aiding digestion, providing a lift, etc.), cigarette advertisements also relied upon doctors’ testimonies to quell fears.

The industry was particularly interested in breaking the traditional taboo on women smoking, and their publicity henchmen employed two appalling measures to do so. The first was to ally the cigarette to the cause of suffrage and women’s empowerment more generally. Thanks to the machinations of public relations progenitor Edward Bernays, debutantes marched proudly in the 1929 New York City Easter parade lighting up their Lucky Strikes as “torches of freedom.” After this well-crafted stunt, women smokers were seen as “bringing about a new democracy of the road,” and by the late ’30s surveys showed that most women at college were smokers.

The second and, of course, contradictory tactic was to raise anxieties about a new modern female body image. In 1928, Lucky Strike got Amelia Earhart in an ad with the tagline: “For a Slender Figure—Reach for a Lucky Instead of a Sweet.” In addition to offending the National Confectioners Association, the campaign also drew fire from critics who claimed that they were marketing to children, which, of course, they absolutely were. Tobacco companies knew early on that lifelong smokers typically begin smoking before the age of 18, and while they couldn’t ever officially market to what the industry called “replacement smokers,” they have crossed about every line there is to cross (see: Joe Camel).

The success of cigarette advertising was resounding: in 1950, 90 percent of consumed tobacco was in the form of cigarettes, up from 5 percent in 1904. The cigarette was sociable even though it stunk; it represented autonomy even though it created dependence. As E. Ruth Pyrtle asked in 1930, “has there ever been in all history so colossal a standardizing process, such a vast demonstration of the sheeplike qualities of the human race as in the spread of the tobacco habit?” There probably hadn’t.

To say that the cigarette epidemic was “engineered” would, however, not be quite right, for even its creators were surprised by the dramatic cultural shift they were able to enact. New sociological and psychological tactics were in play, tactics now cynically accepted as the norm in the media world but which were baffling and terrifying at the time. Advertisers themselves “were concerned that extravagant claims, paid testimonials, and aggressive competitiveness” were threatening the legitimacy of advertising itself and sought to create internal norms to rein in certain excesses.

By 1950, however, they had to change up their strategy, and in such a way that assured that even the smallest twinge of moral feeling was repressed. Damning studies of the link between cigarettes and lung cancer had been published, and doctors were quitting smoking in droves. Tobacco advertisers finally sobered up after the no-holds-barred romp of the ’30s and ’40s and now turned their attention to a more somber, and in fact more sinister task: creating scientific controversy. The industry had to be seen as taking the purported risk seriously, while persistently upholding the position, “More research needed.” In 1953 Hill & Knowlton released their “Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers,” accepting “an interest in people’s health as a basic responsibility, paramount to every other consideration in our business” and announcing the formation of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee (TIRC) to study the problem.

The TIRC was, of course, no research committee, and its director, C.C. Little, was an industry shill. But under the close guidance of Hill & Knowlton, it succeeded in keeping cigarette sales rising through the ’50s and ’60s through the dissemination of “scientific” counter-information. As Allan Brandt writes in his masterful The Cigarette Century (a core source of information for this article):

Hill & Knowlton had served its tobacco clients with commitment and fidelity, and with great success. But the firm had also taken its clients across a critical moral barrier…. By making science fair game in the battle of public relations, the tobacco industry set a destructive precedent that would affect the future debate on subjects ranging from global warming to intelligent design. And by insinuating itself so significantly in the practice of journalism, Hill & Knowlton would compromise the legitimacy and authority of the very instruments upon which they depended.

But maintaining a position of public agnosticism on the dangers of smoking was more than just a marketing strategy. By the ’60s industry lawyers saw no other choice than to maintain this position or else incur legal risk. Big tobacco thus found itself in quite a pickle when the Federal Trade Commission, on the heels of a scathing Surgeon General’s report in 1964, demanded warning labels on all cigarette packages.

The tobacco industry proved as cunning in avoiding regulation as it had in advertising. When the FTC finally acted, the industry proposed its own favorable legislation to avoid the possibility of stricter regulations. Thus when the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act was passed in 1965, it prohibited states from requiring their own warning labels and imposed an ambiguous standardized warning: “Caution: Cigarette Smoking May Be Hazardous to Your Health.” (To this day, cigarette warning labels remain far weaker in the United States than in many other places: FDA initiatives to include terrifying pictures of corpses and cancerous lungs, which some evidence does suggest reduces people’s likelihood of picking up a cigarette, have been stymied by the industry.) This was more than just a successful watering-down of a known fact: by including a warning label on their product, a label that saddled them with no culpability, the tobacco industry created the cornerstone of a powerful legal argument to use in its own defense.

In 1983, attorney Marc Edell filed a complaint against four major tobacco companies on behalf of Rose Cipollone. Cipollone had been a smoker since the age of 16, and she would die of lung cancer less than a year into her suit. When the jury finally rendered a verdict on June 3rd, 1988, they awarded $400,000 to Rose’s husband Antonio Cipollone, marking the first successful judgment against Big Tobacco.

But the jury also ruled that Rose Cipollone was primarily responsible for her own death, and that the tobacco companies were not guilty of fraud and conspiracy. Edell had tried to demonstrate that Cipollone was addicted to cigarettes, but Americans weren’t yet ready to burden smokers with the heavily stigmatized term “addict.” Cipollone was no addict, said the industry lawyers: she knew very well the risks involved in smoking, and thus was ultimately responsible for her own death. She smoked for over 40 years: what did she expect?

This “assumption-of-risk” defense, used in all similar suits, was a carefully crafted one. The industry could not of course come out and admit that cigarettes were actually dangerous. Instead, they “contended that the ‘controversy’ regarding smoking and health was well-known and highly publicized; as a result, plaintiffs were well-informed of any ‘alleged’ risks.” The introduction of federally-mandated warning labels on all cigarette packs had finally shored up this defense. While deterring few smokers, these labels allowed industry lawyers to point to the package itself: who but a willful risk taker would look at this product and actually use it?

It’s worth meditating on the nature of this argument, because it is common across many domains. “No one knows for sure that X is dangerous. There is a debate about the harmfulness of X, but it’s important to remember that there are two sides to every debate, and we ought to consider both to be fair. That being said, since knowledge of the possible harms of X is widespread, any individual who engages in X must be held responsible for any harms that X causes.” This is not just an argument about smoking. It is an argument about the general responsibility of individuals for social ills, and it is pervasive under capitalism. It shifts blame onto victims even when we know for a fact that a powerful entity has spent giant sums of money trying to influence people’s choices, manipulating their perceptions of reality, and throwing doubt on scientific findings that might give people pause.

Disappointing as the outcome of the Cipollone case was, Edell at least scored one lasting victory: he had gotten his hands on some 300,000 internal tobacco industry documents, which the judge accepted, to the loud protest of the defense attorneys, into public record. These documents were the first breach of the industry’s defenses. They would be further weakened in 1990, when paralegal Merrell Williams released what would come to be known as the “Cigarette Papers,” some 4,000 pages of damning evidence on tobacco giant Brown & Williamson. Unsurprisingly, these documents demonstrated a radical discrepancy between industry statements and industry activity. Despite the 1980s insistence that nicotine had not proven to be addictive, companies had admitted internally for decades that it was. In 1963, the Vice President and general counsel of Brown & Williamson had noted that “we are… in the business of selling nicotine, an addictive drug.”

To many critics, the end of Big Tobacco seemed to be assured by the flood of damning information being made public, but the limits of the impact of this knowledge soon became clear in two stunning failures of corporate journalism. In 1994, when ABC’s broadcast news-magazine Day One released a story about how cigarette companies artificially “spike” their product with extra nicotine to keep people addicted, the network was promptly sued by Philip Morris. Despite the great likelihood of ABC’s exoneration, given the difficulty of proving libel, ABC settled its suit with Philip Morris and issued a public apology. Walt Disney Company was on the verge of buying ABC, and they wanted the suit settled before the deal went through.

Around the same time that ABC was settling, 60 Minutes was preparing to run its interview with Jeffrey Wigand, an industry whistleblower whose travails would later be depicted in the film, The Insider. With the Day One suit fresh in their minds, and in the final stages of a $5.4 billion merger with Westinghouse, CBS executives chose to kill the story. Thus were two of the most important public health stories of the 20th century squashed under the weight of giant corporations growing even bigger.

Having reached the limits of individual litigation and mainstream media reporting, anti-tobacco forces finally turned to mass litigation, where tobacco lawyers couldn’t as easily pin the blame on reckless individuals. Particularly effective were the battles of state attorney generals to recover Medicaid costs for tobacco-related diseases. Mississippi was the first to file such a suit in 1994. In an appeal to the rights of the taxpayers, a member of the team that filed the suit aptly noted, “the State of Mississippi has never smoked a cigarette.” Similar suits soon followed from Minnesota, West Virginia, Florida, and Massachusetts, and in 1997 tobacco executives agreed to a proposed “global settlement,” which would reimburse states to the tune of $365 billion.

Celebrations over the global settlement proved premature, as its enactment required congressional legislation. John McCain’s aggressive attempt to make good on the global settlement was tanked by millions spent on industry lobbying and advertising. The watered-down Master Settlement Agreement, functionally a new excise tax on cigarettes that inadvertently made states dependent on tobacco revenue, was finally passed in November 1998. As Richard Scruggs, a key player in the genesis of the global settlement, noted, “the perverse result of what we did was essentially put the states in bed with the tobacco companies.”

Cigarette consumption reached a high in the United States in the late ’70s at about 4000 cigarettes consumed annually per capita, and has dropped steadily since, with no precipitous drop after 1998 (the year the Master Settlement Agreement passed). By 2016, that number had dropped to 1016. The key turning point was not some new discovery about the harms of smoking but rather one about the harms of not smoking. The industry was able to blame the effects of smoking on individual smokers, but it couldn’t do the same for the victims of secondhand smoke. Anti-tobacco advocates quickly assumed this line of attack, and bans on smoking in public places proliferated. Despite some last ditch distraction efforts—including a planned publicity campaign to shift public health advocates’ attention away from smoking and toward AIDS—big tobacco knew that the good times were over. Knowing all it took to bring smoking into public spaces, the industry understood well the significance of its banishment from public spaces. As health consciousness took over American society—or more precisely, as health became a marker of class in America—cigarette smokers quickly became reviled, asocial creatures, unhealthy members of a backward working class. Cigarettes finally gained the stigma anti-tobacco advocates hoped for, and sales plummeted.

That being said, cigarettes are far and away the deadliest drug in existence, not in the Mad Men ’50s but today and for the foreseeable future. According to a recent Health and Human Services report, smoking kills 480,000 people in the United States every year. For reference, that’s “more than AIDS, alcohol, car accidents, illegal drugs, murders and suicides combined.” This means that cigarettes are still the leading cause of preventable deaths in the United States. Even more disturbingly, the American epidemic has been exported worldwide: the slow decrease in cigarette consumption in the developed world has been complemented by a sharp increase in the developing world. Today the fastest machines can produce 20,000 cigarettes in one minute, and regulations in rich countries certainly aren’t turning them off.

This is not simply a case of the “glamour” of American consumption practices being aped by third-world teenagers but rather one of very pointed efforts to crush foreign, state-run tobacco monopolies—which generally helped keep smoking prevalence down—in the name of “open markets.” While reducing cigarette consumption at home, the Reagan and Bush administrations both pushed for a liberalization of tobacco trade, a move rightly compared to the opium wars of the 19th century. Thanks to their successful efforts, it became clear early in the 1990s that growing cigarette consumption was undermining the marked gains in international public health—especially in China’s newly opened market—and the WHO developed the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in 1999 to deal with the problem.

The FCTC finally came into effect in 2005, obligating all participating countries to “implement strong evidence-based policies, including five key measures: high tobacco taxes, smoke-free public spaces, warning labels, comprehensive advertising bans, and support for stop smoking services.” The FCTC was ultimately silent on the problem of trade liberalization, but that didn’t stop British American Tobacco from calling the attempt to “foist” developed world health standards on the developing world a new “form of moral and cultural imperialism, based on assumptions that ‘west is best.’” Out of “respect for cultural diversity,” BAT opposed “calls for global regulation and standards” as a “‘one size fits all’” approach.

A recent study on the effectiveness of the FCTC comes to predictable conclusions: while reducing tobacco use in countries that have adopted the key demand-reduction measures (the developed world), it has not done much to reduce tobacco use in countries that have not adopted such measures (low- and middle-income countries preyed on by the tobacco industry). However, even in developed nations, smoking prevalence rates are drawn along class lines: in 2010, the overall smoking rate in China (28.1 percent ), which houses ⅓ of the world’s smokers, was less than that in West Virginia (28.6 percent ).

Brandt aptly illustrates the paradox at the heart of the cigarette tragedy:

It has been conservatively estimated that 100 million people around the world died from tobacco-related diseases in the twentieth century. Through the first half of that century, the health risks of smoking had yet to be scientifically demonstrated. In this century, in which we have known tobacco’s health effects from the first day, the death toll is predicted to be one billion.

This projection is largely predicated on the lack of regulatory structure in the developing world, but part of the problem here must be that a good number of people today are taking up smoking in full awareness of its destructive consequences. How do we make sense of this fatal insufficiency of knowledge?

As we have seen, the story of the cigarette is the story of the blurring of the line between advertising and reality, of the shaping of innermost desires by corporate memoranda, of the intentional obfuscation of the truth in scientific inquiry and in journalism, of the growing responsibility of individuals for social ills, of the breaking down of barriers by crises of overproduction, and, above all, of a pleasure perfectly suited to capitalism. Short and contained like a pop song; a meaning-giving ritual in the absence of meaningful structures; “an ersatz act which absorbs the increasing nervousness of civilized man.”

In Cigarettes are Sublime, Richard Klein argues that we ought to appreciate this attractiveness of the cigarette if we are to truly overcome it. He fears that the straightforward discouragement of anti-tobacco advocates, in ignoring the “sublime” aspect of smoking, does not actually discourage, and in fact:

…often accomplishes the opposite of what it intends, sometimes inures the habit, and perhaps initiates it. For many, where cigarettes are concerned, discouraging is a form of ensuring their continuing to smoke. For some, it may cause them to start.

Klein argues that “the moment of taking a cigarette allows one to open a parenthesis in the time of ordinary experience, a space and a time of heightened attention that give rise to a feeling of transcendence, evoked through the ritual of fire, smoke, cinder connecting hand, lungs, breath, and mouth.” He calls this experience “l’air du temps,” the meditative remembrance of situatedness and embodiment that punctuates the day through ritual exit.

Klein tends to focus on the meaning that is acquired through smoking, though many of his examples offer a darker view: an important point of reference for Klein, Jean-Paul Sartre also finds great meaning in the act of smoking, but describes this meaning in terms of “appropriative, destructive action.”

Tobacco is a symbol of “appropriated” being, since it is destroyed in the rhythm of my breathing, in a mode of “continuous destruction,” since it passes into me and its change in myself is manifested symbolically by the transformation of the consumed solid into smoke. The connection between the landscape seen while I was smoking and this little crematory sacrifice was such that as we have just seen, the tobacco symbolized the landscape. This means then that the act of destructively appropriating the tobacco was the symbolic equivalent of destructively appropriating the entire world. Across the tobacco which I was smoking was the world which was burning, which was going up in smoke, which was being reabsorbed into vapor so as to re-enter into me.

Perhaps beyond calming and meaning-making, it is this straightforwardly destructive element of cigarette smoking that is ultimately the source of its appeal. Following Klein’s logic, we should assume that people start smoking today not in spite of the health risks but because of them. Every cigarette puff is a daring “Fuck You” to the neoliberal ethic of self-care, at the same time that it is an internalization of the burning Earth in miniature. “L’air du temps,” as Klein seems to know, is also “la suffocation du temps,” the open parenthesis followed soon, with short breath in constricted lungs, by a closed parenthesis. People today smoke because they are nervous, and they smoke to lend sense to the day. But they also smoke because they are at the end.