Life in Revolutionary Times: Lessons From the 1960s

In the 1960s, people around the world fought for revolutionary change. What can we learn from them?

“We can’t afford a scenario where it comes down to Donald Trump with his nostalgia for the social order of the 1950s and Bernie Sanders with his nostalgia for the revolutionary politics of the 1960s.” — Pete Buttigieg, Feb. 25, 2020 (deleted tweet)

“There were times when I found Reverend Wright’s sermons a little over the top… Often, they sounded dated, as if he were channeling a college teach-in from 1968 rather than leading a prosperous congregation that included police commanders, celebrities, wealthy businesspeople, and the Chicago school superintendent.” — Barack Obama, A Promised Land

There was a period in my life around age 13—and now I can hardly believe I did this, but I did—when I would only listen to music recorded between 1965 and 1969. I was very strict about this. “Abbey Road” was okay, because even though it was released in 1970 it was recorded in 1969. “The Who Live At Leeds” was not okay, because while the songs on it were from the ’60s, the concert itself took place in February of 1970. A difficult case was Jimi Hendrix’s “Band of Gypsies“ album, which had been recorded at concerts held on New Year’s Eve 1969 and New Year’s Day 1970. Was it Sixties? Or was it Seventies?

This was, of course, bonkers. I have thankfully shed my obsessive youthful tendency, and come to appreciate the music of many eras and many lands. I now understand units of temporal measurement are an artificial human construct and that nothing magically changed on the day a seven displaced a six in the calendar. But it was not entirely arbitrary of me to select those particular five years out of the entire span of cosmic time. The ’60s, particularly the later ones, have a special place in the American collective memory. Those who grew up during the time often speak like some weird spell came over the world for a few years. “That time changed all of us, and scarred many,” Annie Gottlieb writes in Do You Believe in Magic? The Second Coming of the 60s Generation. “Between 1965 and 1970, all the mental and social structures we’d grown up with were trashed in an orgy of anguish and extravagance, political outrage and cosmic revelation, drugs ‘n’ sex ‘n’ rock ‘n’ roll.”

Gottlieb interviewed countless Baby Boomers who described themselves by saying things like “60s people are like an island, different from everyone around us” and “I feel like an exile in time.” SNCC activist Casey Hayden called her days in the movement a “holy time” that she has sometimes “longed for so profoundly.” Hunter S. Thompson likened the coming and going of the era’s zeitgeist to the cresting of a great wave, but warns those of us who want to understand that “no explanation, no mix of words or music or memories can touch that sense knowing that you were there and alive in that corner of time and the world.”

Certainly, a hell of a lot of things happened in the ’60s in very rapid succession, and many were profoundly different from anything Americans had seen happen before. After gliding through the staid Eisenhower era, the story goes, the country suddenly exploded, politically and culturally. Lenin’s observation that “there are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen” seems particularly applicable to those years, during which something new and often unprecedented was happening seemingly every week. SNCC, CORE, and SDS were challenging the existing racial economic hierarchy. Martin Luther King expanded his public demands to encompass not just civil rights but an end to American imperialism and capitalism. Students went on strike and occupied administration buildings. Groups like the Yippies and the Diggers pushed anarchistic and utopian alternatives through stunts and “happenings.” Women’s liberation, gay liberation, the American Indian Movement, the United Farmworkers—marginalized people decided they had had enough and organized themselves.

Any attempt to enumerate what happened in those few short years goes on and on. Vietnam. The environmental movement. The consumer movement. Love-ins, be-ins, freak-outs, and acid tests. Malcolm X, then the Black Panthers. The creation of Kwanzaa and “Black is Beautiful.” The Free Speech Movement, the Back to the Land Movement. The Mississippi Freedom Summer. The uprisings in Detroit and Los Angeles. The Young Lords and the Chicano movement. Student strikes and the occupation of administration buildings (“Two, three, many Columbias”). The spread of uprisings around the world, from the Movimiento Estudiantil in Mexico to the Prague Spring to May ‘68 in France. Film and literature were changing (e.g., the Latin American Boom, the French New Wave). LSD was horrifying the government with its potential to make people think new thoughts and “drop out” of decent society.

The stunning amount of musical innovation—Motown and “Sgt. Pepper” and Stax and folk-rock and heavy metal and proto-punk and “James Brown Live at the Apollo” and psychedelic pop; top 40 hits had fuzz guitars and Moog synthesizers and mellotrons and sitars. Could the chants of “Black Power,” the Panthers patrolling with semi-automatic weapons and berets, have been anticipated during the run of Leave it to Beaver (1957-63)? As Eldridge Cleaver put it in Soul on Ice, things had suddenly begun “deviating radically from the prevailing Hot-Dog-and-Malted-Milk norm of the bloodless, square, superficial, faceless, Sunday Morning atmosphere that was suffocating the nation’s soul.” It was something else, and you can easily tell why living through it may have been bewildering.

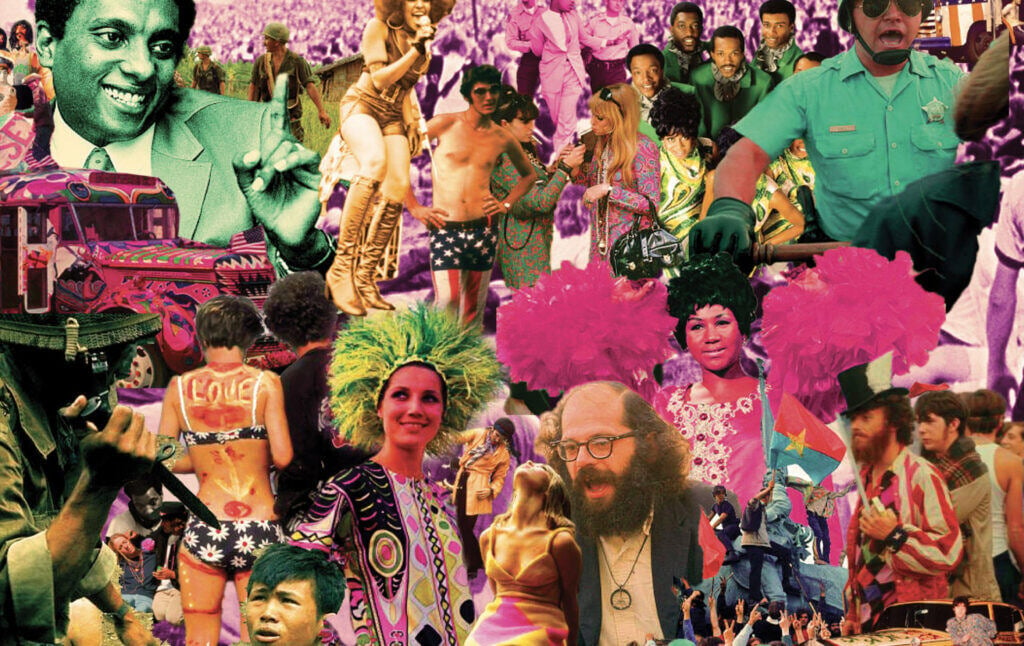

It is very difficult to write about the 1960s without lapsing into stock images and clichés and familiar names. This turbulent decade was transformational, there was social upheaval and generational conflict during which people questioned authority. The ’60s come to us as a collage and the collage is always the same: Allen Ginsburg, Martin Luther King, love beads, The Beatles, Walter Cronkite talking about the Tet offensive, riots in the streets, etc. It is the Boomer memory-stew seen in Forrest Gump, a succession of striking pictures with a groovy soundtrack. Since, as Thompson said, it is impossible to actually get an understanding of what it felt like to be alive at the time, those of us who didn’t live through it are left looking at a set of artifacts and trying to fathom the civilization that must have produced them.

Importantly, even to talk about “the 60s” or a “generation” obscures certain facts. For one thing, there is no such thing as “what it was like to be alive at the time,” because people’s experiences were so varied based on their position in society. The portion of Americans who were hanging out in the Haight-Ashbury district in San Francisco (which is about 10 blocks long in its entirety) or participating in the Freedom Rides, is vanishingly small. Hardly anyone was actually at the 1968 Democratic National Convention protests, which is one reason the Chicago police were able to brutalize the demonstrators with such impunity.

The ’60s are often talked about as if “everything changed” from the 1950s. But for many people, the Big Social Changes filtered down to the individual level only in scraps. Overheard conversations, snippets heard on the news, things seen briefly out a car window. My father, for instance, was working in an aircraft factory in the late ’50s and still working in an aircraft factory all through the ’60s. He remembers seeing hippie folk-rocker Donovan, pre-fame, out playing his guitar on the grass in Hatfield, England, when both were teens there. He had also vaguely known the future lead singer of The Zombies when they were at school. I believe this is the sum total of the interactions my dad had with the ’60s counterculture.

Some people’s ’60s (especially middle-class American white people who were not drafted, who could enjoy the Monterey Pop Festival and see light shows at the Fillmore) may have been worthy of nostalgia, but for those sent to Vietnam, their dominant memory from the period might be: being extremely frightened, watching friends die violently, or killing a stranger. (Of course, with “All Across The Watchtower” playing on the radio in the film version) For the people of Vietnam, the ’60s were not the slightest bit groovy. They were terrifying years in which the country was bombed to smithereens and a million people died. If you were an Indonesian communist in the mid-’60s, you would likely have been among the 500,000 to 1 million people murdered as part of an anti-left purge. If you were a Polish Jew in 1968, you may have been declared an enemy of the state and forced to leave the country, and if you were a Black resident of Zimbabwe (then absurdly named “Rhodesia” after the same British racist for whom the prestigious Rhodes Scholarships are named) or South Africa you may have been engaged in a difficult and perilous struggle against white supremacy.

But the wild divergence of individual experiences, the fact that a “social trend” used to define an era may be made by only a small percentage of people, does not mean we must avoid all generalizations, and what we truly cannot afford to do is talk about a mere turbulent time. “Turbulence” is liberal-speak; it suggests that the delicate social order was unbalanced and needed righting. The ’60s are best understood as a decade of uprising against an intolerable status quo, met with extreme violent resistance and backlash. The same thing happened over and over, in different permutations. The Black Panthers tried to build an independent Black revolutionary party that declined to moderate its demands for freedom. They were infiltrated, arrested, and sometimes murdered. Reformists in the Czech Republic attempted to democratize the country, and were crushed by the Soviet Union. Protesters in South Africa marched against apartheid, and were massacred by police. Cops tried to raid the Stonewall Inn and arrest its patrons for the crime of being gay, only to find that the patrons were disinclined to comply this time, and instead issued cries of “Gay Power!” and refused to be arrested, with men in drag fighting the police physically (and winning), in part by joining together in a can-can style kick line dance and kicking the cops while shouting “We are the Stonewall girls / We wear our hair in curls! / We don’t wear our underwear / To show our pubic hair!” to the tune of “Ta-Ra-Ra Boom-De-Ay.” (Yes, this happened.)

Sometimes they succeeded and sometimes they didn’t. The Stonewall uprising kept the police at bay, and stood at the beginning of a 50-year gay rights crusade that would end up bringing fully legal same-sex marriage to a homophobic country. The armed Black students who took over a building at Cornell helped bring about Black Studies departments in American universities. (Right-wing economist Thomas Sowell calls the armed uprising “the day Cornell died.”) The country is moderately less sexist and racist now, and while we must be careful to note that this is only true relatively speaking—i.e., because white patriarchy was so total in the 1950s—it happened because people made it happen. Men can wear long hair without getting pulled over and roughed up for it. The environmental movement got us an actual federal agency charged with environmental protection, while the consumer movement got us at least some government action to prevent the sale of unsafe and defective products.

For people like Pete Buttigieg and Barack Obama, the phrase “The ’60s” connotes chaos, a bit too much radicalism, things getting out of hand. They see only the collage: those crazy times when all that stuff was happening. Sometimes the ’60s are even spoken of as a time of excess democracy, when people got drunk on the idea of freedom and started going crazy. But we know better: Black Power, gay liberation, feminism, the New Left—they were good, actually. The ’60s radicals won and they lost—the Reagan Revolution destroyed some of their accomplishments and turned the clock back. But everything they did win made the country and the world better. They were on the right side.

When we see the ’60s this way, what it becomes is not a Turbulent Time Of Upheaval, but an unfinished revolution, a moment when a lot of people became idealistic and raised their expectations of what was possible and necessary, and started putting in incredibly hard and dangerous work in order to make their dreams come true. We know that, but many of us don’t think that much about it, because the ’60s have been sanitized and softened. The “I Have a Dream” speech is repeated so often in snippets, so cynically invoked by “colorblind” racists, that hardly anyone remembers that it praised the “marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community” and spat at “gradualism”:

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of Now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice.

Colorblind? King called for a militant, urgent, uncompromising fight for racial justice. He didn’t just demand integration, but economic equality: “the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.” He called for a permanent condition of dissatisfaction until “justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.” (And King was criticized by fellow activists for being too compromising.)

Those of us on the left need to start examining the movements of the ’60s closely, even if eventually the counterculture was subsumed into the culture and some of the organizations fell apart and some of the leaders sold out or turned conservative or became bitter. After all, what happened was a series of awakenings in which people began to think and act in new ways, to challenge that which was previously accepted. That was true of the civil rights movement, of course, a sudden shift from quiet resistance to white supremacy to loud and confrontational resistance. But it was also true on the cultural side. LSD genuinely did expand minds and make people think, despite the bad trips. The importation of Eastern spiritual traditions may, in retrospect, seem somewhat cheesy and even offensive (and the hippies’ casual appropriation of Native American clothes is often painful to look at today). Yet it was good for Americans to stop thinking of “Western Civilization” as the only culture with value.

The ’60s generation did create permanent political and cultural changes, and while it’s tempting to downplay the extent to which the United States has made moral progress (unequal country then, unequal country now), doing so risks understating the accomplishments of social movement participants. Some of the changes were remarkable in their rapidity. At the beginning, half of the country was literally an apartheid state. The atmosphere was unbelievably stifling and repressive. Lenny Bruce was arrested for saying that if we’d lost World War II “Truman would have been strung up by the balls”—to mention Harry Truman’s balls was considered a matter requiring state intervention! Abortion was a crime. Annie Gottlieb quotes a woman who distinctly remembers being told that she needed to stop smiling so much if she ever wanted to be married. But then, women who had been expected to obey their husbands suddenly decided to give a giant middle finger to the patriarchy. They did not actually “burn bras”—though at one protest they did throw some bras into a “Freedom Trash Can.” But they made new demands despite intense hostility and violence. (Think about the hostility that gender studies departments get even today and then imagine what it was like for those who were trying to create these departments in a country where spousal rape was legal in every state.)

I am probably not telling you anything you don’t know, but I do think we ought to contemplate it more. (Frequently the problem is not that people don’t know things but that they don’t think about them enough or work through their implications.) We should do this not merely for the purpose of being grateful to activists like Herbert Lee and Medgar Evers and Viola Liuzzo who died because they believed in equality, but because we, too, are people in a society that needs work, and they offer an example. Those that come out of the ’60s radical tradition like Jeremiah Wright and, well, Bernie Sanders—who was getting arrested at desegregation protests in his teens—have a sense of moral urgency and commitment that people like Buttigieg and Obama lack, which is part of why young people flocked to the Sanders campaign. It was fresh and new, because it was old.

I recently interviewed Lee Weiner, who was part of the Chicago 7, and was struck by how he did indeed seem like a person out of a different time. He had a pure and energetic idealism that was jarring. He wasn’t cynical, even thought he had no illusions. It did feel strangely dated. It did feel ’60s. But it also felt good. I wished more people were like that. I’ll take beautiful hippy dippy flower children over the doomsaying. ’60s leftism has a sincerity to it, the audacity to say words like love and mean them. Power to the people. Give peace a chance. They meant it. CORE leader Floyd McKissick declared: “1966 shall be remembered as the year we left our imposed status as Negroes and became Black Men.” This kind of transformative ambition (this year!) is audacious. But why settle for scraps? And why wait?

On the ground, it did appear as if things were changing overnight. Peter Berg of the radical Diggers collective recalls how it looked:

One day the doorman at the Village Gate was a guy in a coat and tie, complaining about a bunch of weirdos showing up. A couple of weeks later, it’s a new guy, only he’s wearing a beard, lots of jewelry, and a leather vest, and a leather pouch hanging on his side. It really felt like we were in the forefront of a massive social transformation. American society of the 1950s was being left behind. There was a lot of cracking of walls, and there was going to be a flood. But was it going to be up to the ankles, the knees, or the neck? It was a very exciting time.

Things did happen that seem almost unimaginable today. When the British Home Secretary (a Labour Party member) tried to give a talk at Oxford University, students tried to throw him in a fish pond in protest of the Vietnam war. In fact, the spread of radicalism to elite institutions was remarkable. Consider this exhortation produced by students at the Harvard design school during the 1969 student strike there:

Today a good part of the social order has been restored, and the university’s students are dutifully bound for McKinsey and Goldman Sachs. The students do not go on strike or stage armed takeovers of administration buildings.

It can be very rewarding to comb back through all the “’60s stuff” and try to see it with fresh eyes, to defamiliarize ourselves and appreciate it anew. For instance, I recently went back and listened to some of Pete Seeger’s live albums, the ones where the audience sings along. I used to find sing-a-longs cheesy. No longer. I tried to hear “We Shall Overcome” the way it sounded to the people singing it. When you do it that way, it can bring you to tears.

There’s a lot of rubbish from the ’60s, and some very bad ideas. The attraction to Mao and Castro among some leftists was, to say the least, unfortunate. The “White Panther Party” was a solidarity organization for its counterpart, not a white supremacist group, but that’s not something you want to have to explain at the beginning of every conversation. The drug culture produced some great art, but broke a lot of lives. I liked the Merry Pranksters’ colorfully-painted bus, but they seem to have done little but drop acid and hang out with the Grateful Dead. Timothy Leary seems like he was a goofball. When you read the announcement for 1967’s “Human Be-In” it’s impossible to take seriously:

A new concert of human relations being developed within the youthful underground must emerge, become conscious, and be shared so that a revolution of form can be filled with a Renaissance of compassion, awareness, and love.

Far out. But what the fuck does it mean? Still, I want to suggest that there’s value even in this. There’s something charming about it. It’s drivel, yes, but sweet drivel. I’m not going to make fun of people for being this idealistic, for believing that an actual renaissance of love could take place. I wish some people believed that today. Everyone I know seems to think we’re doomed. In the midst of the Cold War, there was just as much reason to believe the world was doomed, but a few people dared to be utopians and felt that not only could you make marginal improvements to the operation of the political system, but there could be a society-wide change in people’s entire consciousness. Consider the 1962 Port Huron Statement’s sincere utopianism:

Theoretic chaos has replaced the idealistic thinking of old—and, unable to reconstitute theoretic order, men have condemned idealism itself. Doubt has replaced hopefulness—and men act out a defeatism that is labeled realistic. The decline of utopia and hope is in fact one of the defining features of social life today. The reasons are various: the dreams of the older left were perverted by Stalinism and never re-created; the congressional stalemate makes men narrow their view of the possible; the specialization of human activity leaves little room for sweeping thought; the horrors of the twentieth century symbolized in the gas ovens and concentration camps and atom bombs, have blasted hopefulness. To be idealistic is to be considered apocalyptic, deluded. To have no serious aspirations, on the contrary, is to be “tough-minded.”

It’s a mistake to write off all stuff that feels dated, because some of it has great value and should be appreciated more. Take, for instance, the peace sign. It has utterly lost its meaning today. People might see it and think the word peace, but it certainly doesn’t conjure up the original aspirations of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament toward a world free of advanced weaponry where all nations lived in harmony. Instead, it’s so closely associated with cartoonish hippiedom that hardly anyone wears or displays it sincerely (save for the cartoonishly hippieish). British artist Gerald Holtom, who created the peace sign for the CND in 1958, during a moment of personal despair, combined the semaphore symbols for “N” and “D,” and was also inspired by the position of the peasant’s arms in Goya’s painting “The Third of May 1808,” which depicts the execution of Spanish resisters to the Napoleonic occupation.

The peace sign was immensely effective—everyone knows what it means. It may be one of the most well-designed logos a social movement has ever had. In fact, it’s too well-designed, because it became iconic, and having become iconic, it became vague. It does not mean to us what it meant in the 1960s, when it was fresh and seeing it might have made you think about how insane nuclear weapons are. But perhaps we ought to bring it back, proudly and without embarrassment. Perhaps all that language about changing consciousness, All You Need Is Love, “turn on, tune in, drop out”—well, maybe instead of cringing or laughing we can take it a little more seriously. Not that we should do it all again. (I’m not going Back To The Land, thank you very much, and I would have detested the mud-caked Woodstock experience—though I am persuaded by my Current Affairs colleague Garrison Lovely’s argument that America would be better off if more people did psychedelics). But we could be just a little bit inspired.

The visible manifestations of cultural and political change, the stuff you actually witness, can seem to occur by some magic force. That force is often spoken of in the passive voice—people were moved, the country was changed. The force’s origins and directions were murky. It seemed unguided. It was a mishmash of things that all happened all of a sudden and then seemed to slow down.

But it’s people who do things, not “spirits of the era,” and there are all sorts of forgotten individuals whose work we can look to and draw on for present-day inspiration. Richard Oakes of the American Indian Movement, for instance, organized the seizure and occupation of Alcatraz Island by a group of Indians, an occupation that lasted 19 months and successfully touched off a new indigenous rights movement. Oakes was 30 when he was shot to death by a white racist, and one important reason the ’60s movements “died” is that so many great potential leaders were literally murdered (see also: Fred Hampton). The achievement of Oakes and the AIM in holding out against a federal siege for so long (with the government cutting off power and water) should have made him a household name, but so many great projects and people from the time are forgotten.

I am always finding out about figures and actions I overlooked before; I only recently heard of Doris Derby, who co-founded the Free Southern Theater, which traveled around the South putting on free-admission all-Black productions of everything from Ossie Davis’ Purlie Victorious to Samuel Beckett’s Waitng for Godot in rural Black areas. Derby was from New York City, and to go into Mississippi as a young Black woman during Jim Crow to put on theatrical productions took idealism and courage. She may even have been called unpragmatic—surely voting rights came first, theater second? But the Free Southern Theater worked, and was popular wherever it went. It died in 1980—free tickets can’t keep a theater going, and the wealthy couldn’t give a shit about letting sharecroppers have great theater—at the beginning of the Reagan years and the end of so much that had been accomplished.

Underground newspapers and magazines and comics, G.I. coffee houses—there was even an independent leftist wire service, the Liberation News Service, to compete with the AP and give college newspapers an alternate source for national news stories. Some of the books of the New Left are still worth going back and reading, like Kwame Ture and Charles V. Hamilton’s Black Power and C. Wright Mills’ The Power Elite. I keep a bunch of out-of-print ’60s books around for inspiration. The New Left was intellectually rich, focusing primarily on race, gender, and economic justice but also critiquing culture, technology, and the bureaucratic structure of the university. Paul Goodman, forgotten today, was a utopian anarchist whose Growing Up Absurd caused many young people to start questioning the American Dream and demanding a more meaningful existence. Valerie Solanas is known today mostly for her art criticism (specifically, she shot Andy Warhol) but her SCUM [Society for Cutting Up Men] Manifesto is an extraordinary piece of writing that begins with the most memorable opening sentence for a manifesto since “a spectre is haunting Europe”:

Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and destroy the male sex.

It gets more aggressively radical from there. (Read it.)

Every time I open a leftist book published in the ’60s, I feel both refreshed and saddened. Saddened because the spirit of the times largely melted away, but refreshed at finding new comrades. I draw little bits of insight here and there. I don’t subscribe to Herbert Marcuse’s social analysis, but I always think about a point he makes in One-Dimensional Man about the way acronyms eliminate meaning—eventually we come to talk about the U.N. rather than the United Nations, which slowly turns our conception of it into a bureaucratic agency rather than a project to unite all nations. When Elizabeth Warren ran for president, one reason I was so cynical is that I remember a passage in Vine Deloria, Jr.’s 1969 Indian manifesto Custer Died For Your Sins about how remarkable it is that white people always have Cherokee grandmothers. Deloria is not the only one to notice the phenomenon itself, but he specifically notes the fact that the tribe is always Cherokee and it’s always a grandmother rather than a grandfather—Deloria speculates that this is because an “Indian princess” is romantic while an Indian man is still seen as savage. This is the tiniest scrap from a brilliant book, one I wish I’d been assigned rather than having to discover through personal curiosity about the ’60s. From Abbie Hoffman to Jane Jacobs to Murray Bookchin to Angela Davis, reading works by 60s idealists has sharpened my moral vision and turned me into a more cheerful and committed person.

Our task, 50 years after the end, is not to be nostalgic for the ’60s or to try to recreate them. They were a dark and violent time, and while there’s much to love in the clothes and music and movies, the Vietnam War was such an atrocity that it makes viewing the era through rose-colored day-glo granny glasses seem twisted. Depoliticized portrayals like Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time In Hollywood, which eliminates the dark side of the ’60s by literally imagining an alternate reality in which the Manson murders did not take place, miss all the stuff that matters. ’60s radicals did change their society for the better. They didn’t create a utopia, and many of their projects failed. But the country, and the world, were better off because of the work that hundreds of thousands of individuals put in, because of their creativity and their refusal to accept that the way things are is necessarily how they have to be.

Anyone who feels the need for more social transformation here and now should study the ’60s, not to see them through the haze of white Boomer nostalgia—times that happened and then ended and are not coming back—but as offering live and relevant lessons. The reduction of the ’60s to a collage of chaos has obscured what is most important about that time, namely that a lot of people woke up and started trying to remake their world. Their work should have been the beginning of something that it is our job to pick up and continue. We need to figure out what went wrong and what went right, and to understand that what went right can happen again, if we make it.

I have made a Spotify playlist to accompany this article, because it wouldn’t be a Sixties thing without a soundtrack, would it?