How Billionaires See Themselves

Reading the dreadful memoirs of the super-rich offers an illuminating look at their delusions.

Most billionaires stay out of the public eye. This makes sense, because according to polls, far more people distrust billionaires than admire them, and the overwhelming majority of the public want the government to seize a portion of billionaires’ wealth. It’s easy for anyone in possession of a billion dollars to make their name widely known, but evidently wealth without fame is preferred to fame without wealth (or the possibility of losing a small chunk of wealth).

Some billionaires, however, write books. These are some of the only documents that the ruling class has produced for the consumption of the masses. What is it they wish us to know?

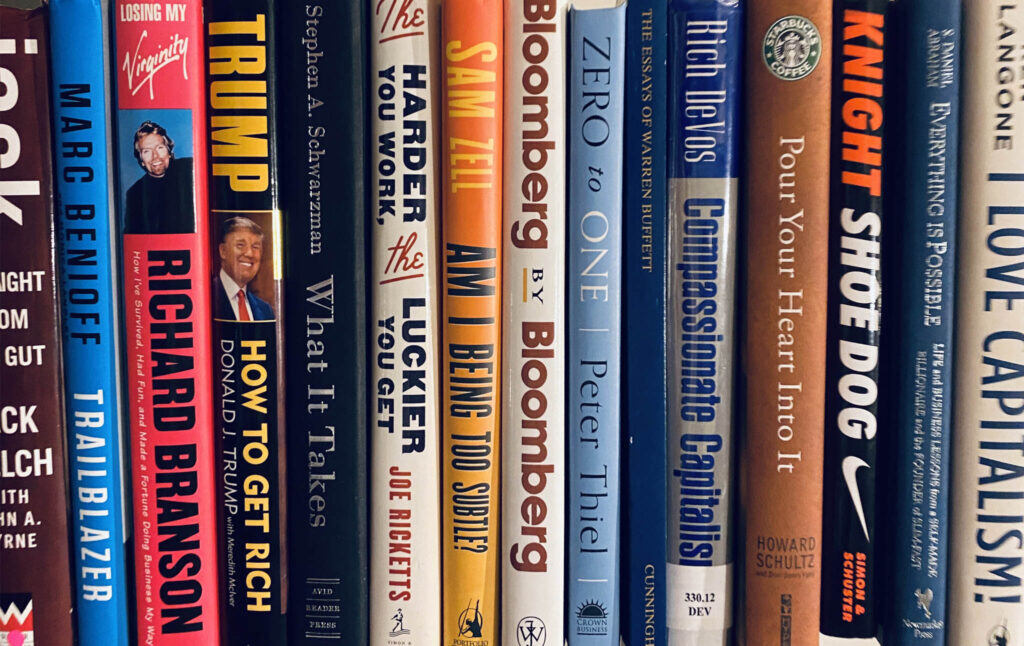

I have on my desk a stack of “billionaire books,” mostly memoirs. They include: Sam Zell’s Am I Being Too Subtle, Richard Branson’s Losing My Virginity, Richard DeVos’ Compassionate Capitalism, Charles Koch’s Good Profit, Ken Langone’s I Love Capitalism!, Stephen Schwarzman’s What It Takes, Peter Thiel’s Zero to One, Marc Benioff’s Trailblazer, Sam Walton’s Made in America, Joe Ricketts’ The Harder You Work, The Luckier You Get, and Michael Bloomberg’s Bloomberg by Bloomberg. (What a title. Bloomberg, whose company is Bloomberg L.P., also made his fortune on a device he invented called “the Bloomberg,” so it is clear he likes saying “Bloomberg.”)

What you may have noticed even from the titles of these books is that many billionaires are slightly defensive. Koch Industries, for instance, is significantly invested in fossil fuels and has been fined hundreds of millions of dollars for violations of environmental regulations. Charles Koch, however, wants us to know that he makes “good profit,” by which he means that he creates “value for others” rather than just enriching himself. Richard DeVos (Amway) and Marc Benioff (Salesforce) have actually both written books called Compassionate Capitalism. John Mackey (Whole Foods) called his Conscious Capitalism. “I am good,” they are saying. “I am not what you think. Please don’t hate me.” (The plea falls on deaf ears; to me, all of these books might as well be titled Expropriate Me.)

Some, like Ken Langone (Home Depot), are a little less concerned with appearances. Titling a book I Love Capitalism! is bold for a billionaire, since it invites the obvious reaction: “Yes, well, of course you do. It gave you a fucking billion dollars. If you were the king you would probably write a book called I Love Monarchy! but it wouldn’t tell us much about whether monarchy is good for anyone else.”

Langone, for his part, is refreshingly unabashed in his defense of having far more than the rest of us:

Should I follow the Bible? I’ll be honest: I’m not giving everything away. Why? Because I love this life! I love having nice houses and good people to help me. I love getting on my airplane instead of having to take my shoes off and wait in line to take a commercial flight. You want to accuse me of living well? I plead guilty… I don’t know if I would have done what I did or sacrificed the time I’ve sacrificed if I didn’t see something in it for me. If that’s greed, let the chips fall where they may…As I said, I’ve been rich and I’ve been poor, and rich is better.

Even Langone, however, insists that what he does is not about the money, and that money is last on his list of priorities. In fact, if there is a central recurring theme to billionaire literature, it is this: an insistence that what has made the billionaire rich is helping other people rather than helping themselves. The billionaire wants to explain to us that what might look like the steady hoarding of wealth and a feudalistic imbalance of power is, in fact, the product of defensible moral choices and a fair system. As Max Weber noted, “the fortunate is seldom satisfied with the fact of being fortunate” but wants to know that “he has a right to his good fortune,” and that it is “legitimate fortune.” Hence Joe Ricketts’ (Ameritrade) “the harder you work, the luckier you get.” It’s manifestly untrue, but it helps Ricketts avoid guilt over his luck and privilege.

Christianity has elaborate “theodicies:” attempts to account for the “problem of evil,” a.k.a. reconciling the existence of God with the fact the world is clearly unfair, since the most obvious other option is atheism. The rich have their own theodicies: attempts to account for the obvious unfairness of their own position and to find some explanation for the world being the way it is, because the most obvious other option is socialism.

No billionaire, as far as I’ve read, claims to have been enriched unjustly. They each acknowledge the role of luck in success, but they do not believe the game they won is fundamentally unfair. Each wants to tell us the story of how hard they worked, how it delivered benefits for people, and how obtaining a billion dollars was simply a pleasant side effect of their pursuits rather than the ultimate aim.

Interestingly, what’s implicit in this is that greed is not, in fact, good. A billionaire has to make the case that they did not simply want money (even if, as Langone says, it is nice to have money), because they recognize that pure selfishness is almost universally frowned upon. (Even Trump’s The Art of the Deal opens with the sentence: “I don’t do it for the money.”) In these books, each billionaire presents themselves as a moral person who cares about people other than themselves. The writing overflows with false modesty, as the billionaires tediously detail their philanthropic contributions so as to prove that they “give back.” And they tell us that while the money is nice, it is not why they do what they do. If we take them at their word, this means that the usual argument that high taxes reduce incentives is false. After all, every rich person says they don’t do it for the money, so presumably they would keep doing exactly the same thing if we took most of that money away.

Another way to legitimize their wealth is to justify the system by which it is accumulated in the first place. There is an underlying deep conviction that financial gain must be distributed according to some rational formula, that the Invisible Hand of Market Justice gives each his due:

- “Society rewards those who give it what it wants. That is why how much money people have earned is a rough measure of how much they gave society what it wanted—NOT how much they desired to make money. Look at what caused people to make a lot of money and you will see that usually it is in proportion to their production of what the society wanted and largely unrelated to their desire to make money. There are many people who have made a lot of money who never made making a lot of money their primary goal. Instead, they simply engaged in the work that they were doing, produced what society wanted, and got rich doing it” — Ray Dalio (Bridgewater)

- “In a truly free economy, for a business to survive and prosper in the long term it must develop and use its capabilities to create real, sustainable, superior value for its customers, for society, and for itself… The role of business in society is to help people improve their lives…. Profits are a measure of the value it creates for society.” — Charles Koch

- “This is what we know to be true: business is good because it creates value, it is ethical because it is based on voluntary exchange, it is noble because it can elevate our existence, and it is heroic because it lifts people out of poverty and creates prosperity.” —John Mackey

This last passage could serve as a kind of “capitalist catechism,” a statement of the core ideology that the billionaire “knows to be true.” Business creates value for society, and thus it is good. This has radical implications: it means not only that it is legitimate to make as much money as you can, but it could even mean that the more money you make, the better a person you are. If, as Dalio says, fortunes are distributed in proportion to the degree someone “gives society what it wants,” then the person with the most money has done the most to satisfy other people. Price is equal to value.

Even other billionaires, however, question the theory that the most socially beneficial people earn the most money. Peter Thiel confessed to business students that innovators do not actually tend to get rich. The people who get rich are monopolists: those who see an opportunity to control something that very large numbers of other people need, and who can eliminate competition. In fact, while Langone presents himself as the “co-founder of Home Depot,” which gives people a sense that he created something real from which they benefit, elsewhere in the book he reveals that one way he made a giant pile of money was simply by finding a way to gain control over an important patent for a widely-used laser component. The man who actually invented the component was unable to enforce his patent, so Langone set him up with a lawyer—in exchange for a piece of the rewards, which turned out to be substantial. The end result of this for “society” was that every time anyone purchased a device containing this laser component, it was more expensive, so that Ken Langone could reap indefinite benefits from a government-enforced monopoly on a piece of knowledge that he did not create.

Many billionaires do not seem to produce anything at all. Ray Dalio, for instance, runs a hedge fund, meaning he makes bets. Richard Branson is known for Virgin Mobile and Virgin Atlantic, but Losing My Virginity reveals how little Branson actually contributed to the ventures that were making him his fortune. For instance, when Branson was running Virgin Records, the label was constantly trying to scout out a hit artist. They found a gold mine in multi-instrumentalist Mike Oldfield, whose Tubular Bells was one of the best-selling albums of the 1970s. Branson did not write or produce Tubular Bells. He simply owned the company that put out the album.

Now your first instinct may be to think: “Well, but this is an important contribution. Branson connected the artist to the listeners. The record label doesn’t do nothing. The actual music is only one of the inputs into the ultimate product, an album.” But this theory wobbles a bit as we witness more of what Branson’s company was actually doing. For instance, in the early 1990s there was a bidding war for Janet Jackson, whose next album was widely expected to be a sure-fire hit. Branson wanted to win that war, because he believed having Jackson on the label would not only make them a bunch of money, but would also enhance Virgin’s reputation as a place for cool and trendy artists.

Branson won the war, put out Jackson’s album, and it was a huge hit. But note something: if Richard Branson and Virgin had not existed, nothing would have changed from the public’s perspective. Jackson was hugely popular and someone was going to put out her next album. Branson did not actually add any value. Nothing happened because of him, except that (1) Jackson’s albums said Virgin on them instead of another label and (2) the marketing strategy was possibly different than it would have been under a different label, but the consensus was that given Jackson’s popularity whichever label got the next album would have a hit on its hands no matter what (3) Jackson got slightly more money than she would have if the bidding war had one fewer participant.

This latter factor might make it seem like Branson helped Jackson. But that’s only the case if we assume the legitimacy of the capitalist system. In fact, the reason Jackson needed to go to a billionaire record label owner in the first place is that the billionaire record label owner controls the “means of production and distribution.” Having several record labels bid for her work allows the laborer (Jackson) to sell her labor at a higher price, but the whole reason she has to sell it at all is that she doesn’t have ownership of the means of production and distribution. Let us imagine an alternate situation in which those means were socialized; let’s say we have public recording studios like we have public libraries, and a public means of distribution (like, for example, an artist-owned Spotify). Here, the artist would benefit far more from a successful album, because there would be no Branson taking a cut.

In the book, it is not obvious that Richard Branson cares at all about music. In fact, he happens to know a guy named Simon who has taste in music, and that guy does the recruitment and discovery. When Branson talks, it is solely about how he can reap the fruit of other people’s talents: how can they find an artist that will make the label a lot of money? Often, these are artists that the label is almost certain will make it big eventually, but if the company can be the first to sign them, they will get the slice that would otherwise go to someone else. They are not lifting up unappreciated geniuses who would otherwise never get opportunities.

For a look at what “entrepreneurs” actually “innovate,” look at Nike founder Phil Knight. Nike is, first and foremost, a brand: a world-famous name and swoosh. But the woman who designed the swoosh logo, graphic artist Carolyn Davidson, was paid $35 for it (Knight later lied and said it was $75.) Knight didn’t even like the design when he saw it. In Shoe Dog, he says that when she showed him her proposed logos, “the theme seemed to be… fat lightning bolts? Chubby check marks? Morbidly obese squiggles? Her designs did evoke motion, of a kind, but also motion sickness. None spoke to me.” Eventually he accepted the swoosh because there were no alternatives. Likewise with the name: Knight wanted to call the company “Dimension Six,” but “Nike” came to one of his employees in a dream. When Knight heard it, he commented: “It’ll have to do… I don’t love it. Maybe it will grow on me.” (Years later, when the story was infamous, Knight did make a big show of giving Davidson some Nike shares.)

We might say, of course, that the Nike brand is not the core of Nike, that the shoes matter as well. But Knight did not invent a new kind of shoe. Instead, he simply noticed that Japanese shoes were high-quality and could be obtained cheaply. By being the first to import these superior foreign shoes, he was able to wring giant piles of money out of Americans for goods made by the Japanese. It was as if he was the first American to go to Mexico and “discover” the taco, and realized he could make a fortune because Mexicans hadn’t yet tried selling tacos to Americans.

Being “first” is a big part of how successful billionaires make their fortune. Mark Zuckerberg did not create the “best” social network. He just made one at the very moment when such a thing was possible but hadn’t happened yet. By being first, it’s possible to get large enough where “network effects” keep other entrants out of the market. It’s almost impossible to launch a competitor to Facebook or Twitter now, because they were the first to scoop everybody up. PayPal was not the most brilliant payment processor imaginable. But they came along when an online payment processor happened to be a thing people needed. Sam Zell talks in his memoir about the importance of the “first mover advantage.” When the 1996 Telecommunications Act eliminated restrictions on the number of radio stations that any one person could own, Zell started snapping up distressed radio stations around the country at bargain prices. Eventually he had a giant network of them that he sold to Clear Channel for $4.4 billion. Zell doesn’t indicate that he did anything to improve the radio stations, or even that he had any interest in radio. He just knew that radio stations could be sold for more than their existing prices. In other words, absolutely nothing might change about a company or an industry, but someone like Zell can swoop in and make a giant load of money from it.

The radio station case is an example of trying to control as much of something scarce as you can. There are a limited number of licensed radio stations, so Zell just tried to buy up what he knew other people would soon need and have to pay him for. There was no innovation. Just seeking power. Thiel’s Zero to One openly offers straightforward guidance to the smart capitalist: get a monopoly on something rather than invent something extremely socially useful that can be copied easily. Zell agrees, and has said that “the best thing to have in the world is a monopoly, and if you can’t have a monopoly, you want an oligarchy.”

Zell recalls another example of a time he cornered a market and made a fortune. He discovered that a small, troubled company named American Hawaii Cruises had a monopoly on cruise travel to Hawai’i, because U.S. law prohibited foreign-made ships from doing intra-U.S. travel. (Remember, “free trade” rhetoric is all a sham, the United States is a deeply protectionist country.) By buying the company, Zell was able to make sure that he was the one who profited, rather than someone else, but it wasn’t because he was so good at running the company. He calls himself the “chairman of everything and CEO of nothing,” and says he doesn’t “involve [himself] in the day to day.” His job is to simply figure out what to buy and then make somebody else run it. (This makes it somewhat funny that he has also said that “the 1 percent work harder” than everyone else and “should be emulated.”)

Zell infamously bought the Los Angeles Times, and demanded that journalists’ work should generate more revenue. “Fuck you,” he said to an Orlando Sentinel photographer who publicly confronted him about his belief that reporters needed to focus more on turning a profit than reporting the news. Did Zell’s increased focus on revenue end up creating more of it? No—after a year, the Los Angeles Times was plunged into bankruptcy, in one of the more well-known cases of a rich guy buying up a venerable newspaper and destroying it.

Bankrupting a popular newspaper hardly “fills a social need.” Some economic activity is nothing more than “rent seeking”—simply trying to collect money without increasing production or value. For example, if you put a fence along a river, and charge people entrance to swim in the river, you’ve contributed nothing to anyone. All you’ve done is extract wealth from people who could previously have used the river for free. A rich person is not necessarily rich because they created value. They might simply, as Marx suggested, have found a way to extract value from the labor of others. As in the case of Zell, they might even lessen the overall value of the labor itself. When we analyze what these men actually do, their social function begins to seem far more questionable.

*

We can also get some insight into how “privilege” works by looking at the ways that these men got their start. Most of them had happy upbringings, or at least did not experience devastating trauma or tragedy. They also had family support. When young Richard Branson wanted to buy a country manor house to start a recording studio, his parents gave him £2,500, and his Auntie Joyce gave him £7,500, the equivalent of around $180,000 USD today, with which he’s able to get Virgin Records going. In 1945, Sam Walton’s father-in-law loaned him $20,000 to buy a store. That’s equal to nearly $300,000 in today’s money. Walton ran the store successfully, bought another store, and slowly built the chain that would become Walmart. His children are now some of the richest people in the world. Walton, of course, calls his a “story about entrepreneurship, risk, and hard work,” the American dream fulfilled. But how likely was a Black person in 1940s Arkansas to have been able to get a giant loan from a rich in-law and sell to a white clientele? Walton won a rigged game. Walmart could not have been created by Black people no matter how hard they worked, and because “first mover” advantage is so important, the first superstore chain was always going to be run by a white person. We can see here a very clear example of how the racial wealth gap is passed down intergenerationally. Because no Black family had accumulated wealth in 1945, no Black person could compete with Sam Walton. Today, Sam Walton’s billionaire children sit on vast fortunes that were created under completely illegitimate conditions—and they think of it as an example of virtue being rewarded!

You can also see why it’s irrelevant to say that billionaires have “worked” for their money. In fact, it’s absolutely true that many of the super-rich work, and work hard. They come into the office early, leave late, neglect their families, and have few interests outside their business. In fact, one notable feature of these memoirs is that the billionaires seem to be utterly “uncultured.” I’m no snob, but you get the sense with many of them that the first time they ever read a book was when the ghostwriter handed them their own memoirs for proofreading. There’s a shocking lack of interest in literature, drama, art, music, dance, history, or anything aside from entrepreneurship. They are bores. I admit, however, that they pour themselves into their work.

But Marx once noted that it doesn’t matter how much a slave-driver works at being a slave-driver when it comes to assessing their function. Walton’s fortune was unearned no matter how hard he worked for it, because he built it under a set of unjust conditions that made his success possible. Likewise, those who stole and “developed” Native American land might have worked quite hard at it, but it doesn’t tell us whether their resulting gains are ill-gotten. (Thieves, too, can put in long hours.)

Another myth of the super-rich is that their rewards come because they have been willing to “take risks.” The capitalist, it is said, earns high returns because they have risked the possibility that they will not. But when you read their memoirs, you actually find that much of what capitalists do consists of trying to find propositions that are all upside, without any risk at all. Zell, for instance, talks about how he noticed before anyone else that mobile home parks were a fantastic investment. People who were in them were generally stuck in them and rarely left, you didn’t have to put much money into maintaining or improving them, and competition was limited by the fact that nobody in a house wanted a new mobile home park near them. So if you bought them, you gained the power to squeeze a great deal of money indefinitely out of residents. The “risk” was trivial.

I often hear defenders of capitalism say things like “well, if you socialists had ever had to meet a payroll you’d think differently” or “a socialist couldn’t run a taco truck.” (In my case this is true, as I do not know anything about making tacos.) But in working with our dedicated and brilliant staff to take Current Affairs from a tiny project operating out of my living room to a successful company with an office and global distribution, I’ve been able to see first-hand why capitalist talking points are false. Certainly, I understand that “founding” a company does not mean that you actually make the thing it produces by yourself. This is always done by a team of people who perform a lot of labor for little public credit.

Take risk, for example. I took no risk. Really, none. If the company ever failed, I wouldn’t be on the hook. I could just walk away and do something else. I didn’t put any money into it that I could lose; we funded ourselves at the start through Kickstarter. The only risk was that the first subscribers wouldn’t get their magazines. But there was no actual risk of that, because it was easy to make sure they did (my cofounder Oren Nimni and I bagged and labeled each and every magazine ourselves, by hand). Now, I made sure that I don’t own Current Affairs myself, that it is a collective enterprise. But if I had retained ownership, then after we hired staff I could have squeezed profits out of it without ever putting anything at risk, simply because I was the person who initially set it up. The reason billionaires make more money than everyone else at their company is that they have the power to demand it, not because they deserve it or worked the hardest or even (in most cases) did the innovating that made the company successful.

They also possess a different mindset than other people. Stephen Schwarzman (Blackstone) recalls a recurring disagreement he had with his father, who owned a small Philadelphia drug store called Schwarzman’s. Schwarzman the younger was constantly telling Schwarzman the elder that he should take the store regional or national. His dad simply couldn’t understand what the point would be.

“We could be huge,” the son says.

“I’m very happy and have a nice house. Have two cars. I have enough money to send you and your brothers to college. What more do I need?”

“It isn’t about what you need. It’s about wants,” says the son.

“I don’t want it. I don’t need it. That will not make me happy.”

In his book, Schwarzman says he shook his head, and couldn’t understand why his father turned down a “sure thing.” Later, he says he came to understand that you “can’t learn to be an entrepreneur.” Dad simply didn’t have the mindset.

Of course, Schwarzman’s dad comes out of this exchange looking perfectly reasonable, and his son still doesn’t grasp the point, even many decades later. It’s not just that money can’t buy happiness. It’s that once you have happiness, the further pursuit of money only detracts from it. But perhaps that’s not true for Stephen Schwarzman, whose lifestyle Vanity Fair describes as follows:

In 2007, he became synonymous with Wall Street excess when, on the eve of the financial crisis, he threw himself a 60th birthday party that featured Martin Short as the master of ceremonies; performances by Patti LaBelle and Rod Stewart; a meal of “lobster, filet mignon, and baked Alaska,” along with “an array of expensive wines”; “replicas of Schwarzman’s art collection” on the walls, “a full-length portrait of him by Andrew Festing, the president of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters”; around 350 guests, including Barbara Walters, Maria Bartiromo, Tina Brown, and Melania and Donald Trump; and a “large-scale replica of . . . Schwarzman’s Manhattan apartment.” Later that year, his culinary preferences—stone crabs that run $400, or $40 per claw—and low tolerance for noise pollution (“while sunning by the pool at his 11,000-square-foot home in Palm Beach, Fla., he complained . . . that an employee wasn’t wearing the proper black shoes with his uniform . . . [explaining] that he found the squeak of the rubber soles distracting”)—were revealed… For decades, Schwarzman, who’s worth an estimated $12.4 billion, has had to suffer through the ignorant public’s hurtful attacks on the private-equity industry and total lack of understanding about what a great public service it provides. Presumably, he wanted to throw himself a lavish 65th birthday party but had to consider the optics of it all, instead waiting until his 70th to celebrate himself at a soirée that included trapeze artists, live camels, acrobats, Mongolian soldiers, “a giant birthday cake in the shape of a Chinese temple,” and Gwen Stefani singing “Happy Birthday.”

Schwarzman, incidentally, is the one who compared Barack Obama’s attempt to slightly raise the top marginal tax rate to Hitler’s invasion of Poland.

The vast difference between the way billionaires think about the world and the way normal people do is one of the more fascinating aspects of these books. Michael Bloomberg begins Bloomberg by Bloomberg with the story of how he was fired by Salomon Brothers in the 1980s, and felt devastated. With his mere $10 million severance package, he says, “I was worried that Sue might be ashamed of my new, less visible status and concerned I couldn’t support the family.” Daniel Abraham (Slim-Fast) says of his childhood home: “When I say the house had fourteen rooms, it probably sounds as if we were rich. But we weren’t. Not at all. Houses were cheap then.” Sometimes it seems like they have been flattered for so long by those around them that they don’t notice how bizarre they sound, and how unusual and unnatural their greed and their aspirations really are.

This is even true in the case of Richard Branson, the “fun” billionaire who people like. (Blurbs from the back of Losing My Virginity, include Newsweek: “He wears his fame and money exceedingly well… he isn’t interested in power [and] just wants to have fun.” GQ: “he embodies America’s cherished mythology of the iconoclastic, swashbuckling entrepreneur.” Ivana Trump: “Richard is good-looking and very smart.”) In a jaw-dropping anecdote about his early days editing and publishing a magazine called Student, Branson relates how he discovered that his co-founder wanted to turn the business into a worker cooperative, and Branson saved the situation by lying and making his friend think the workers hated him:

[H]e had left a draft of a memo, which he was writing to the staff. It was a plan to get rid of me as publisher and editor, to take editorial and financial control of Student, and to turn it into a cooperative. I would become just part of the team, and everyone would share equally in the editorial direction of the magazine. I was shocked. I felt that Nik, my closest friend, was betraying me… I decided to bluff my way through the crisis… [If the staff were] undecided, then I could drive a wedge between Nik and the rest of them and cut Nik out.

[…] “Nik,” I said as we walked down the street, “a number of people have come up to me and said they’re unhappy with what you’re planning. [note: a lie] They don’t like the idea, but they’re too scared to tell you to your face.” Nik looked horrified.

“I don’t think it’s a good idea for you to stay here,” I went on. “You’re trying to undermine me and the whole of Student.”… Nik looked down at his feet.

“I’m sorry, Ricky,” he said. “It just seemed a better way to organize ourselves…” He trailed off.

“I’m sorry too, Nik.” … Nik left that day… I hate criticizing people who work with me… Ever since then I have always tried to avoid the issue by asking someone else to wield the ax.

Beyond telling glimpses like this one, outright psychopathic tendencies do not show up very often in these books. Most, after all, were produced with the aid of skilled ghostwriters whose job is to bury the nasty stuff. The only real way to get past the propaganda is to look beyond the primary sources and examine the facts. Marc Benioff fills his book with page after page about his values and how much his company cares about stakeholders rather than just making money, but shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic began, Salesforce announced that it was laying off 1,000 staff despite having just reported their strongest annual performance ever. Stephen Schwarzman talks proudly about a company he owns called Invitation Homes, which he presents as having given poor people access to good housing after the financial crisis. “I bet if I look up this company it will actually turn out that it does a bunch of shady shit and Schwarzman is an evil slumlord,” I thought as I read the passage. Sure enough, Reuters reported that “in interviews with scores of the company’s tenants in neighborhoods across the United States, the picture that emerges isn’t as much one of exceptional service as it is one of leaky pipes, vermin, toxic mold, nonfunctioning appliances and months-long waits for repairs.” A U.N. working group on human rights and transnational corporations even sent Schwarzman an angry letter denouncing the practices of his company:

Tenants told us that when they ask Invitation Homes to undertake ordinary repairs or maintenance, such as to address plumbing household insect problems, they are charged directly for any undertakings on top of their rent. They also reported that Invitation Homes—through an automated system—is quick to threaten eviction or file eviction notices due to late payment of rent or late of payment of fees (95 USD per incident), no matter the circumstances. If a tenant cannot pay the late fee and if Invitation Homes does not evict, that fee is added to the tenant’s rent. If in the following month the tenant can pay their rent but not the additional charge, the tenant may be evicted for partial payment of rent. When tenants choose to challenge the eviction with Invitation Homes they incur additional fees and penalties.

It is difficult to award a prize for “most evil billionaire” out of the group of 21st century robber barons whose literary output I sampled, but Schwarzman probably gets it for financing a life of utterly obscene luxury by jacking up poor people’s rent and throwing them out onto the street the moment they get behind (and throwing in some fees and penalties for good measure). Just utterly heinous. As the newspaper owner said to the photojournalist: fuck you.

* * *

Much of the behavior we see from billionaires comes from what I’ve come to call “the bifurcated philosophy of accumulation and distribution.” Or, less obnoxiously: it’s okay to be a sociopath when you’re getting the stuff so long as you’re a saint after you’ve got it. The idea is that the world of business is dog-eat-dog and you can be as Machiavellian as you like and don’t need to think about the consequences for anybody’s lives. But then you have to do philanthropy afterwards, because greed is bad. Andrew Carnegie, the O.G. robber baron, laid out the template in his popular Gospel of Wealth. Carnegie begins by justifying every kind of horrific inequality as being the natural order of things, which should be completely beyond question:

The contrast between the palace of the millionaire and the cottage of the laborer with us today measures the change which has come with civilization. This change, however, is not to be deplored, but welcomed…. Much better this great irregularity than universal squalor. It is beyond our power to alter, and, therefore, to be accepted and made the best of. It is a waste of time to criticize the inevitable… We accept and welcome, as conditions to which we must accommodate ourselves, great inequality of environment: the concentration of business, industrial and commercial, in the hands of a few essential to the future progress of the race. The Socialist or Anarchist who seeks to overturn present conditions is to be regarded attacking the foundation upon which civilization itself rests, for civilization took its start from the day when capable, industrious workman said to his incompetent and lazy fellow, “If thou dost not sow, thou shalt not reap,” and thus ended primitive Communism by separating the drones from the bees.

But Carnegie then lays out a theory of noblesse oblige: in return for benefiting from this system, “the duty of the man of wealth” is to “organiz[e] benefactions from which the masses of their fellows will derive benefit.” He will thus be “the mere trustee and agent for his poorer brethren, bringing to their service his superior wisdom, [doing better for them] than they would or could do for themselves.” Now, Carnegie is very particular about who he helps, condemning “indiscriminate charity” and saying that “it were better for mankind that the millions of the rich were thrown into the sea than so spent as to encourage the slothful, the drunken, and the unworthy,” and he is one of those people who says giving to panhandlers actually hurts them and is thus selfish and immoral. But Carnegie’s overall message is: it doesn’t matter how you enrich yourself if you are a “steward” of the public good afterward. Accumulate as you like, so long as you distribute according to the principles of justice.

Except, of course: philanthropy is just as selfish as endless wealth accumulation. A true benefactor of humankind sheds their wealth rather than handing it out in little drops to their pet causes. The philanthropist is no different from a feudal lord who doled out favors. The “unjust accumulation/just distribution” formula is just more ludicrous theodicy, with philanthropy a means of helping these guys rationalize having vastly more luxury and power than everyone else.

Billionaires tell themselves many things. They say that market price is value, meaning that if you’re making money you’re helping the world. They say that they are rewarded for risk and hard work, even though they don’t risk anything of value and people who work far harder than they do earn pittances. They say that they won a “free” contest, when they won a rigged one whose results have no legitimacy. (Is it mere coincidence that these are all white guys?) They say that they are “compassionate” in their capitalist practices but ultimately let the market determine their morality. They say they innovate and add value when they do nothing of the kind. Their justifications for their success crumble when touched. It’s interesting that the ruling class, with all of its resources, cannot mount any kind of persuasive defense of its own position. But to anyone who is secretly insecure, and wonders whether perhaps the people at the top are smarter and better and more hardworking, you will be reassured to know that they are not. You don’t have to take my word for it. It’s right there in their books.