Why the Revolutionary Reporting of Rodolfo Walsh Matters Today

U.S. journalists could learn a lot from Walsh’s fearless coverage of the Argentine military junta.

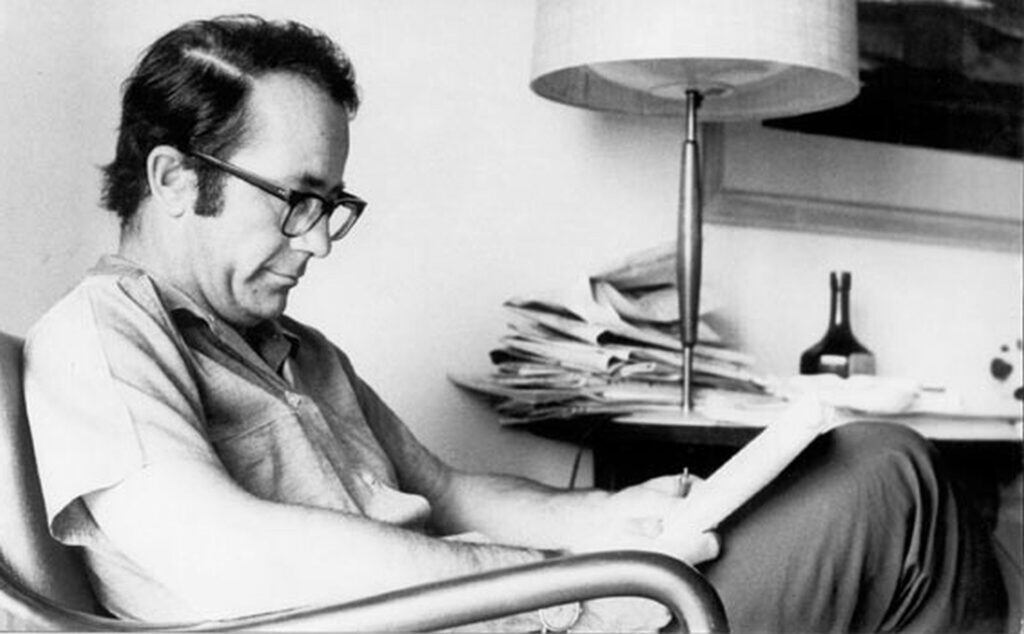

The final moments of Argentinian journalist Rodolfo Walsh’s life are gospel to anyone touched by his testament. They evoke his essence to an extent that seems excessively romantic to anyone with half a sense of reality. But by all accounts, both those of his admirers and the men sent to kill him, Walsh’s death happened how the legend says it happened:

On March 27, 1977, Walsh finished sending some mail in Buenos Aires and began walking down the Avenida Entre Rios. A few neighborhoods away, his daughter María Victoria (“Vicki” to friends and family), a reporter and officer of the Montoneros, a socialist guerrilla group fighting Argentina’s final military junta, had taken her own life at the end of a firefight with the army not six months earlier. In a letter Walsh wrote to his friends, he said her choice was a “mature, reasoned decision.” It was better for his daughter to die right there, he thought, than surrender to the “torture without limit” of the notoriously sadistic regime, which would disappear an estimated 30,000 people before its end—the vast majority of whom would never make it back home. Vicki was 26 when she died, on her own terms, after fighting for as long as possible.

So when soldiers from a nearby detention center approached Walsh, who had been an essential part of the Montoneros’ intelligence operations for years, and ordered him to surrender… well, he was his daughter’s father.

Walsh drew his pistol, ducked behind a tree, and shot it out with the soldiers as long as he could. He managed to hit one of his kidnappers, all but assuring he wouldn’t live long enough to see detention. Then came the answer, in machine gun fire, that put an end to his 50 years of life. His body was thrown into the back of a car and never seen again.

There’s a lot we’ll likely never know about Walsh’s end. We’ll never know if he was shot dead on the street or if he still clung to life as he was disappeared. We’ll never know what went through his head when those soldiers confronted him—if he thought about Vicki when it all went down.

But we do know what was in the mail.

Walsh’s last parcel held what proved to be his most famous work, his Open Letter From A Writer To The Military Junta. Over about a dozen pages, he lays bare the Argentine junta’s crimes with painstaking detail and powerful prose. It reads furious, like words from a man grieving his murdered child.

“By succumbing repeatedly to the argument that the end of killing guerrillas justifies all your means,” Walsh wrote, lashing at the junta, “you have arrived at a form of absolute, metaphysical torture that is unbounded by time: the original goal of obtaining information has been lost in the disturbed minds of those inflicting the torture. Instead, they have ceded to the impulse to pommel human substance to the point of breaking it and making it lose its dignity, which the executioner has lost, and which you yourselves have lost.”

Walsh was hardly the only reporter to condemn the junta’s murderous ways or face reprisal from its henchmen. But the Open Letter rails even more harshly against the government’s neoliberal economic policies, which Walsh calls “an even greater atrocity that is leading millions of human beings into misery.” The junta’s self-proclaimed National Reorganization Process ditched Peronist social welfare policies like nationalization and strengthening labor unions in favor of labor repression and deregulation. His invective predicts the arguments later employed by Naomi Klein in her 2007 book The Shock Doctrine, (which discusses Walsh at several points) as he accuses the junta of using the political crisis to cripple Argentina’s working class and labor movement to the benefit of the country’s oligarchs and international corporate interests. As Walsh writes:

“Over the course of one year, you have decreased the real wages of workers by 40 percent, reduced their contribution to the national income by 30 percent, and raised the number of hours per day a worker needs to put in to cover his cost of living from six to eighteen, thereby reviving forms of forced labor that cannot even be found in the last remnants of colonialism.

By freezing salaries with the butts of your rifles while prices rise at bayonet point, abolishing every form of collective protest, forbidding internal commissions and assemblies, extending workdays, raising unemployment to a record level of 9 percent and being sure to increase it with three hundred thousand new layoffs, you have brought labor relations back to the beginning of the Industrial Era. And when the workers have wanted to protest, you have called them subversives and kidnapped entire delegations of union representatives who sometimes turned up dead, and other times did not turn up at all.”

Walsh took these things down as a warning to the junta whose policies he rightly predicted would lead to its downfall, which came in 1983 following a disastrous attempt to win control of the Falkland Islands from the British. He disseminated the letter, which went unpublished in his frightened homeland and mostly unnoticed abroad, “with no hope of being heard, with the certainty of being persecuted, but faithful to the commitment I made long ago to bear witness during difficult times.” And then he died, leaving that work for his people.

The Open Letter is marked throughout with the proof that it is, at its core, a work of journalism, and recognizable as such to almost anyone. It makes its claims with clear, concise language, and substantiates them with statistics as accurate as one could ever expect in an environment where attempting to gather truth was a revolutionary act. But it is in The Open Letter’s peculiarities to a U.S. readership—specifically its polemical tone, its overtly political nature, and how it chooses to address a regime flagrantly ignoring the law—that its words become relevant decades later and thousands of miles away.

If The Open Letter appeared in the New York Times tomorrow, it would be ridiculed by serious journalists for its activist bent. But Walsh, and the lineage of Latin American writers that led to him, offer us an alternative to a media model utterly baffled in the face of growing right-wing authoritarianism. This is the superior blueprint for journalism that needs to respond to rising fascist currents in a government that controls the most prolific killing machine in the history of humanity.

Anyone striving to learn from Rodolfo Walsh inevitably has to reconcile his dual nature as “a rare man of words and action,” as Irish journalist Stephen Phelan put it. To simply call him a journalist and leave it at that would be neglectful, since his work as an outright revolutionary was at least as influential. This is the guy who spoiled the Bays of Pigs invasion during his time in Cuba, personally decoding CIA communications about the operation and relaying the information to Fidel Castro. While in Cuba, Walsh also helped launch the Prensa Latina to serve as a counterweight to the kind of capitalist media that spent the surrounding decades laundering CIA-backed right-wing coups of democratically-elected governments throughout the Americas. In Argentina, he spent years running intelligence for guerrillas. He died fighting that fight. Personally, I think having the context of just how committed Walsh was to the ideals his work defended does a lot to heighten his writing.

At a glance, it might seem harsh to compare the political climate of the United States in 2020 to Dirty War Argentina, but those distinctions melt away upon examination. Granted, there aren’t bodies washing up by the dozen in Canada the same way they used to wash up in Uruguay, but just about everything else tracks to some extent at least. We have disappearances of protestors into unmarked cars, we have executive-sanctioned death squads, we have concentration camps and lost children, stagnant wages, unrelieved economic suffering and a government that spews wild nonsense as a point of policy. If we call the thing Walsh wrote against an authoritarian regime, we must label this current government the same.

This American far-right movement hits every qualifier in Italian academic Umberto Eco’s political essay Ur-Facism, and seems poised to grow only more insane in the coming years. Faced with the challenge of covering it, American journalism has, at best, struggled, and at worst actively normalized profoundly un-normal happenings in search of its fabled neutral ground. As Current Affairs has argued before, it shouldn’t be that hard to avoid writing long-form profiles of fascists. Although, given the history of the U.S. press, this failure to understand the threat at hand shouldn’t be surprising.

As Dr. Pablo Calvi argues in his book Latin American Adventures in Literary Journalism, Argentina produced a reporter like Rodolfo Walsh, a journalist-revolutionary not dissimilar to José Martí in Cuba or Gabriel García Márquez in Colombia, because journalism in Latin America was forged in response to authoritarianism. The foundational text of Latin American literature and journalism—which are intertwined to a large extent because the push for literacy came after independence from Spain— is Domingo Sarmiento’s Facundo, or Civilization and Barbarism. The book was as much an attempt to accurately chronicle early 19th-century Argentina as it was an effort to galvanize opposition to caudillo (strongman) Juan Manuel de Rosas. While Argentina in Sarmiento’s time was not yet a nation state, it was then, like it was for Walsh, a place where the men with political power wielded it however they pleased, without regard to standards of law and morality.

It’s no coincidence, therefore, that Walsh earned his reputation as a master polemicist when he dug into every detail of a military massacre for what became his seminal work: Operation Massacre, a nonfiction novel that predates Truman Capote’s own In Cold Blood by a decade. Before 1956, Walsh was a fairly liberal chess aficionado who made his living writing short stories and the occasional article. But when the backlash to a failed coup of a coup spilled out into the streets of Buenos Aires, crossing his path along the way, what he witnessed changed him forever.

“I haven’t forgotten how, standing by the window blinds, I heard a recruit dying in the street who did not say ‘Long live the nation!’ but instead: ‘Don’t leave me here alone, you sons of bitches,’” Walsh wrote in the prologue to Operation Massacre. “After that, I don’t want to remember anything else—not the announcer’s voice at dawn reporting that eighteen civilians had been executed in Lanús, nor the wave of blood that flooded the country up until Valle’s death.”

According to Calvi, journalists south of the U.S. border learned to moralize in a way that might strike a Yankee reader as unobjective, because the ethical argument was often the most powerful one to be made when you lived under the thumb of a dictator. Calvi writes:

“Latin American literary journalism has always been imbued with a dominant political undertone, a progressive teleology, a sense of journalistic urgency, and a humane disgust for the aberrations committed by authoritarian regimes. These narratives have consistently expressed concerns for the dilemmas rooted in Latin American political instability, while displaying a moral vision aimed at the democratic establishment—sometimes its restoration—in the region. This mostly anti-authoritarian undertone has not only given the genre an ethical imprint but also resulted in a politically motivated stance that has defined the genre beyond its factual or aesthetic preoccupations… these stories can either be fully loaded with political undertones or plainly interpreted as a novelized historical record.”

Besides the penchant for moralization, Sarmiento also established the notion that a reporter could be a political operative as well. When he sought to portray characters like the strongman Rosas and his titular ally Juan Facundo Quiroga as barbaric, he did so at least partly to make liberal intellectuals like himself seem representative of his notion of civilization. Sarmiento had actually fought the caudillos of the pampas as a younger man, and was exiled to Chile for his part in the conflict. When the decentralized rule of military strongmen gave way to the Argentine Republic, Sarmiento served as its president from 1868-74. Martí would try to play that dual role of reporter and revolutionary in Cuba a generation later—as would Walsh a century thereafter, though neither ever held a political office.

Contrast aside, this isn’t to say that the history of the United States hasn’t been run through with enough violent repression, death squads, and authoritarianism to match Argentina’s. It has. It’s just that up here, the most brutal weapons of the social and political order were rarely wielded against the white male bourgeoisie that came to populate the nation’s fourth estate. Journalism in the U.S. had every reason to develop a more rigorous tradition of advocacy, but until recently almost nobody in America’s media establishment cared about people with a boot on their neck. The luminaries of that early landscape, reporters like Ida B. Wells and Nellie Bly, were pushing against a majority whose work served to uphold white male supremacy. So the horrors of slavery and Jim Crow were ignored or endorsed; the genocide of indigenous peoples was endlessly justified.

With those ideological demons rooted in American journalism, then defended as the neutral ground from which our notion of objectivity sprang, a frightening amount of 20th and 21st century reportage wound up fatally deferential to power. Taken in tandem with committed tilts against the left that went largely unexamined until Noam Chomsky and Edward Hermann’s book Manufacturing Consent began to dig into how market forces influence press coverage, what we get is a news media that treats its ideological opponents far differently than the players whose politics align with its governing corporate interests. It’s why Henry Kissinger, the man whose machinations brought despair to every corner of the world, and whose green light to the Argentine junta kickstarted the terror Walsh’s Open Letter protested, became a friend to so many media landed gentry like Ted Koppel and Marvin Kalb. It’s why the 2019 coup that ousted Evo Morales and massacred indigenous peoples in Bolivia was covered like a victory for democracy. It’s why an essay where U.S. Senator Tom Cotton said Trump should sic the army on protesters in major cities made it into the New York Times.

So today, when dealing with a government the press should grill for committing atrocities, or lying to the public, or sexually harassing staffers, the industry tends toward two dangerous strategies. One is to seek an illusory equilibrium where every action by the reactionary right has an analogue on the revolutionary left. This is the mode of operation that gives us the dreaded “bothsidesism” and endless false equivalencies that see actual Nazis equated with anti-fascists. It’s also responsible for the brain worms that made CNN pundit Van Jones say Trump “became President of the United States” when he said some stuff that wasn’t about deporting Ilhan Omar.

The other response by U.S. journalists to the chaos of our times is characterized by half measures. It is the endless hedging of language; the dancing around the kind of condemnations merited by forced hysterectomies. The litigation of when to use the term “concentration camp” and the million different ways to call Trump a liar without offending Pasadena wine-mom conservatives. Journalists’ few moral appeals, those desperate attempts to reproduce the “have you no decency?” moment, come off as bizarre by contrast because so many media man hours are wasted plotting the Northwest Passage to avoiding emotion.

In this sense, the “biases” of ostensibly objective American reporting seem somewhat similar to the work of a Walsh, a Martí, or a García Márquez. The difference is that camp of journalists made no claim to false neutrality. They strove for accuracy and independence as fiercely as any news gatherers, (Walsh himself once remarked “journalism is either free or it is a farce”) but they also wrote overtly for political effect. The Latin American revolutionary reporters—and more importantly, their readers—knew exactly where they stood and what they were doing.

But rather than state its allegiances outright, American media has used its self-proclaimed neutrality as a cover for the market forces and class allegiances that hold silent sway over newsrooms across the country. Occasionally, almost by accident, the system produces some sort of reckoning. But that show of justice rarely has any staying power. A particularly egregious actor like Trump might draw the sort of scrutiny that journalism biopics are made to deify, but for every condemnation of someone in power there are a dozen siren blasts of batshit crazy CIA propaganda. Nixon might go down, but Kissinger (I cannot emphasize enough how many reporters loved Kissinger) and J. Edgar Hoover and the poison systems that produce them keep sowing their salt. When nothing really changes, it’s no surprise that people begin to doubt the motives of the industry that calls itself the defender of democracy.

Recently there’s been something of a groundswell in the industry to refocus perspective in a way that would truly make American journalism a “voice of the voiceless,” as countless J-school professors and teary-eyed movie monologues have so often claimed it to be. Individual reporters like Ken Klippenstein, Aura Bodago and Robert Evans have embraced a style more reminiscent of Walsh than noted idiot Bob Woodward. This is the right move, and needs to be embraced on an institutional level.

Does that mean that every time people like Kissinger come up in an article the story should pause to note that they’re horrible people? That would rock, but probably no. Still, something as simple as an outlet allowing its reporters to be upfront about identifying as socialist (or just thinking imperialism is bad) and then continuing on with their work without having to contort around those beliefs to try and hold a job would reduce a lot of agita for readers and writers alike.

It’s hard to know what lessons Walsh’s work will teach to people who explore it. It’s possible to see his legacy as proof the written word can really be a force against abuse. Walsh’s name and work came up during prosecutions of Dirty War criminals decades later. The men who killed him were themselves arrested for the crime back in 2005. They’re sitting in prison right now.

But there’s even more in Walsh’s story that points to how inadequate reporting can be without direct action. If Walsh himself hadn’t understood that, April 17 would probably be a national holiday in a capitalist Cuba. Arumburu, the hand that moved all the evils in Operation Massacre, was brought to justice by the Montoneros in 1970, executed in retaliation for what his men did to Valle. The only trial he ever faced was run by the guerrillas who shot him in the head. Walsh’s final public act wasn’t publishing the Open Letter in defiance of the junta, it was firing a gun at its agents. Revolution, after all, is no dinner party.

Most journalists in the U.S. aspire to status and access, to the kind of prominence and security that comes with clawing your way to the highest rungs of an industry’s ladder. But to play that game well enough to advance that far means supplicating at the feet of empire, endlessly churning out P.R. for the powerful while deriding anything that challenges the prevailing order. Walsh showed us what it means to live a life in opposition to that power. As bloody as his end was, he left a legacy infinitely more respectable than legions of bootlicking reporters before or since. His example should be exalted as the ideal voice of the voiceless, a model for how to bear witness with your honor intact. Taking his example, a more oppositional and politically honest media class, unafraid to make an ethical point, drift into advocacy or even direct action, might not be such a compliant cog in this country’s imperial machine.