Biden’s Election Is Not A Mandate For Centrism

The painful, floundering ordeal of centrist Joe Biden’s win is not, in fact, a great case for his (lack of) politics.

Earlier this year, Nation columnist Katha Pollitt was criticized for saying that she would vote for Joe Biden over Donald Trump even if Biden “boiled babies and ate them.” Biden had recently been accused of sexual assault by a former Senate staffer, and Pollitt argued that the truth of the allegations was irrelevant to whether Biden should win the presidential election, since “taking back the White House is that important.”

After Biden won the primary, I was forced to agree with Pollitt that the overriding importance of ousting Donald Trump meant that shameful and even criminal behavior on Biden’s part had to be set aside temporarily in the context of the election. (Although I understand my colleague Briahna Joy Gray’s worry that if we announce beforehand that baby-eating is not disqualifying, future baby-eaters will feel no disincentive to continue their pursuits.) Likewise, strictly speaking, David Sedaris is right that a general election is a menu with only two dishes on it, one of which is a “plate of shit with broken glass in it” (the Republican Party), although I think the analogy tends to disguise just how bad the other “menu option” can be. I voted for Joe Biden because I am realistic: I understand that while “being a warm body who is not Donald Trump” is a very low standard, it is true that in an election with only two possible outcomes I would vote for anybody who wasn’t quite as bad as Trump.

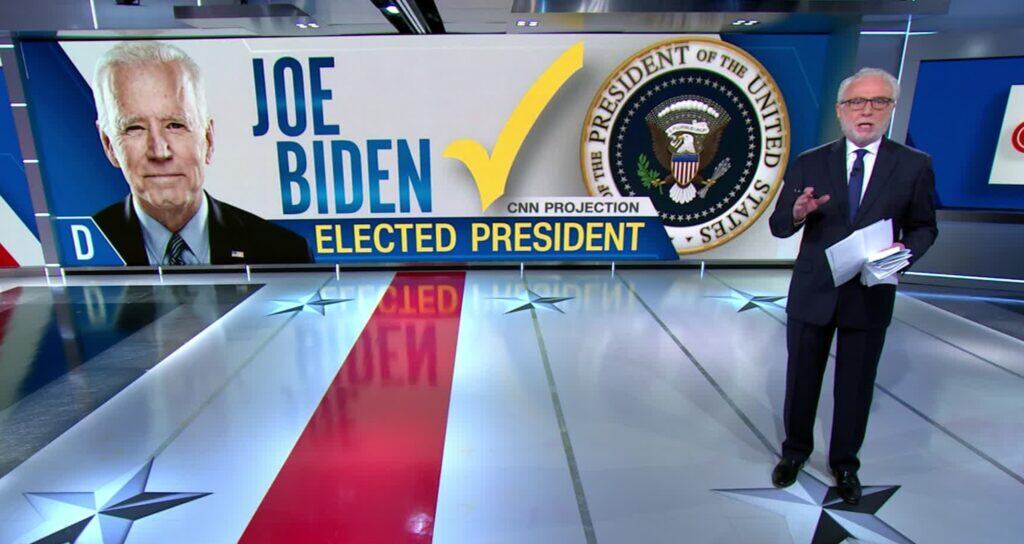

Now Joe Biden has won, and I am a bit relieved. But already, those who agree with Joe Biden’s conservative Democratic politics are arguing that Biden’s win is proof that voters endorse and want centrism. Republican governor Larry Hogan of Maryland says that Biden has a “mandate for moderation” and that the election clearly shows voters “desperately want” elected officials who work on “bipartisan, common-sense solutions.” Charles Blow of the New York Times says that Biden won partly “because he espoused many of the same centrist policies and positioning” as Barack Obama.

At the most elementary level, the logic here does not work. Democrats spent the whole year telling progressives that no matter how much they disliked Joe Biden, they needed to choke down their vomit and pull the lever for him, because the stakes of a second Trump term were too high. Leftists listened; far fewer voted for the Green Party than the number of right-leaning people who voted Libertarian, a difference that may well have helped put Biden over the top. We fell in line, because we understood that voting for Biden was not an endorsement of his values and ideas (or his past), but a harm-reduction measure aimed at ousting Trump by whatever distasteful means necessary.

If plenty of us voted Biden, then, because “a ham sandwich would be better than Donald Trump,” Biden’s victory proves absolutely nothing about the kind of politics voters actually want. Biden squeaked in by uncomfortably small margins in many critical states. Lots of people who voted for him did not like him. I recently overheard a snatch of conversation between two middle-aged men in a cafe, one of whom voted for Biden because he liked Biden and one of whom voted for Biden because he hated Trump. The second man mentioned to the first that the Democratic Party had sold out working people, and the first thought that this was too cynical, and talked about how much worse the Republicans were. Conversations like this occurred all across the country leading up to election day, and from the election result alone, it’s impossible to tell how many voters were like the first man and how many were like the second.

Of course, everyone is inclined to see the election as confirmation of their own pre-existing political beliefs. Being a leftist, I look at the fact that Florida passed a $15 minimum wage at the same time as voting for Trump as confirmation that Democrats have a lot of work to do when it comes to regaining some portions of the working class. Centrist Democrats, however, immediately started blaming progressives for the party’s losses in Congressional races. The centrists’ theory is that even if losing candidates did not personally campaign on ideas like Medicare For All and defunding the police, the fact that leftists put these ideas into the discourse successfully allowed Republicans to paint Democrats as a party of radical socialists.

The fact that everyone will see the election through the lenses of their own ideology does not mean that all interpretations are equally irrational; it’s still quite possible for one analysis to be substantially more grounded in facts than another. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has vigorously disputed the idea that the election in any way indicted progressive ideas. She’s noted that Medicare For All cosponsors in swing districts won reelection. (Brian Kahn of Gizmodo notes that Green New Deal cosponsors did very well, too.) Of course, there’s plenty of polling (even from Fox) showing that progressive policies play well among the general public, who generally want higher taxes on the rich and government healthcare.

The “people crave centrism” narrative crumbles when confronted with facts. Here, the New York Times’ Astead Herndon asks Conor Lamb, a moderate member of Congress from Pennsylvania, to respond to the polling:

In the Democratic primary, even as progressive candidates lost, polling showed that their issues remained popular among Democrats. Even things like single-payer health insurance or things like the Green New Deal. What’s your response to that?

At the end of the day, it’s individual candidates that have to win races, and then work with their fellow officeholders to pass bills into law and change people’s lives. So you can tell me all the polling you want, but you have to win elections. And I’ve now been through three very difficult elections in a Republican-leaning district, with the president personally campaigning against me. And I can tell you that people are not clamoring for the two policies that you just asked about. So, that’s just what probably separates a winner from a loser in a district like mine.

“You can tell me all the polling you want” should be understood to mean “I do not care what the best available data tells us about what the public actually wants me to do in office.” Lamb sees the fact that his elections were “difficult” but he still won them as proof that he is correct to run away from the Green New Deal and Medicare For All. But that’s not obviously the case. He might be right that his district is just too conservative, and if he promised a big climate infrastructure bill, it would sink him. But we might equally well conclude from the evidence he has provided (none) that he is having difficulties in part because he is not offering his voters compelling solutions to the problems of climate change and the high cost of healthcare. Ryan Grim has compiled data showing that Democratic candidates’ vote share in swing districts tends to diminish as they move right. I know Lamb, with his stated commitment to ignoring data, would probably laugh at this, because it goes against the conventional wisdom about how you win voters. (Move right, and then if you lose, move further to the right.) But what if the conventional wisdom is actually faulty? The possibility must be considered, especially as we see democratic socialists running successful campaigns by rejecting it, and instead going on the untested principle: “What if we picked our positions on the basis of what was right rather than what we thought was expedient and then worked to try to persuade people of that right thing even if it was ‘radical’?”

To those of us on the left, it is extremely frustrating to see the sensible social democratic policies we believe in described as a kind of toxic extremism that will ruin the Democratic Party’s electoral fortunes. This is partly, as I say, because that is the opposite of what we can tell from the actual polls, which people like Lamb simply have to ignore. But it is also frustrating because the Green New Deal and Medicare for All are not extreme. They are pragmatic. When I see someone like Mitt Romney on television pledging to fight against the GND, I do not see a “realist.” I see someone who is completely delusional. What, after all, is his plan for dealing with climate change? Is someone going to ask him what he believes the alternative to the Green New Deal is, and why he believes it would match the scale of the problem we face? How does he propose to ensure that people don’t have to worry about money when they go to the doctor? Why does he think that the kinds of single-payer insurance systems that work effectively around the world are somehow a crazy idea? Why do we need a for-profit private insurance industry hoovering up people’s money instead of having it go directly toward paying for their care? Centrist politics are not actually “reasonable.” They are deeply unreasonable, and once we understand that, we are far less likely to think they should naturally prevail at the ballot box. Why would a lack of ambition to solve serious problems be more persuasive to voters than effective (if ambitious) policies designed and endorsed by some of the world’s top economists?

Larry Hogan, in his op-ed about the “moderate mandate,” says that while “placating the far-left base” was an “effective campaign strategy” for Biden, it must be abandoned now that Biden pledges to be a “unifier” president. Instead, he must be committed to “bipartisanship.” It is, first, delusional to think that Biden tried to placate the far-left base during his campaign—if deliberately attacking Medicare For All and the Green New Deal and repeatedly insisting you’ll preserve fracking is “placating the left,” I’m not sure what it would look like to run from the left. But it’s also important to be clear what Republicans like Hogan mean by “unify.” It’s easy to nod and agree when they speak of “sensible, bipartisan” solutions, and being a president for all the country instead of just the blue states, etc. Being sensible is good. Unity is good. But ultimately, any understanding of political reality has to begin with the realization that Republicans do not want to do anything that will repair some of the most serious problems with the status quo. They do not want climate legislation. If they were to grudgingly let it through, it would only be because they’d managed to guarantee something utterly ineffectual. This is because a serious response to climate change is going to be expensive and is going to have to take on the fossil fuel industry. It’s also going to have to be radically economically progressive, because if the costs of addressing climate change fall disproportionately on the working class, there will be popular revolt (as there was in France with the gilets-jaunes protests).

Already, there are troubling signs that the Biden administration is going to accept the logic that “the best way to attract mass support is to do as little as possible.” Republicans are being looked at for Cabinet posts. The Biden transition team’s “priorities” website leaves off a number of promises that were made during the campaign—notably, it does not yet promise any rollback of Donald Trump’s cruel immigration policies, which should be a Day 1 item. In Washington, it is so hard to do anything big and ambitious that it will be very tempting for the Biden administration to convince itself that the American public actually doesn’t want the administration to do anything ambitious. We must fight that myth, in part because unless Biden changes the country in ways that are visible in people’s lives, Trumpism may be back soon with a vengeance.

A lot of nonsense is going to be said in the next months and years, and we must fight back against it. The first bad talking point is that centrism has been vindicated or endorsed. It has not, and Democrats need to shed this dangerous delusion sooner rather than later.