A Guide For High School Students On How To Avoid Propaganda

It is extremely difficult to tell the frauds and charlatans from the truth-tellers. Be vigilant and learn to think critically.

In the 14 years since I graduated high school, one of the most important things I have realized is just how difficult it is to figure out what is true, and how easy it is to accidentally find yourself believing something completely false. When we read history, sometimes we wonder how people of other times could have believed things that seemed obviously absurd. Until shockingly recently it was believed that babies did not feel pain. Romans believed drinking gladiator blood could cure epilepsy. Sometimes, charismatic leaders can convince ordinary people of ludicrous and terrifying delusions. Cult leader Jim Jones persuaded hundreds of his followers that they needed to move to a remote outpost in Guyana and kill themselves with poisoned fruit juice. Hitler, of course, got perfectly normal Germans to believe that they had an obligation to exterminate millions of their fellow citizens in order to somehow “purify” their country.

It would be nice to think that we ourselves are smarter, that we could never end up being so delusional. But anyone can be fooled, for a very obvious reason: most of our knowledge isn’t arrived at rationally. We develop our understandings of the world through trusting what other people are telling us. That does not just go for religious believers. All of us have to have “faith” that we are being told the truth, because it is impossible for us to prove all the things we need to believe. George Orwell noted that most people believe the Earth is round not because they have personally deduced it to be the case, but because they have been taught it. Orwell said that if we encountered a Flat Earther who asked us to prove it, many people would struggle. Orwell himself was somewhat confident he could deal with a Flat Earther, but less sure he could take on someone who argued, say, that the moon is a flat disc. Orwell concluded that:

It will be seen that my reasons for thinking that the earth is round are rather precarious ones. Yet this is an exceptionally elementary piece of information. On most other questions I should have to fall back on the expert much earlier, and would be less able to test his pronouncements. And much the greater part of our knowledge is at this level. It does not rest on reasoning or on experiment, but on authority. And how can it be otherwise, when the range of knowledge is so vast that the expert himself is an ignoramus as soon as he strays away from his own speciality? Most people, if asked to prove that the earth is round, would not even bother to produce the rather weak arguments I have outlined above. They would start off by saying that ’everyone knows’ the earth to be round, and if pressed further, would become angry.

Orwell was not here making a claim that there is any doubt about the shape of the Earth. Instead, he was making a point about the ordinary person’s necessary reliance upon authority. We ourselves cannot simultaneously be astronomers, statisticians, historians, chemists, doctors, journalists, geographers, economists, and climate scientists, so we must all rely on experts to be telling us the truth.

It sounds perfectly reasonable to trust that an expert knows what they’re talking about. A climate scientist knows more about the climate than I do, so if I don’t know the science, surely it’s reasonable for me to defer to the verdicts of those who do know. But what if I read two works by two people who both claim to be climate scientists, and they disagree with each other? Unless I take a few years off and try to get a PhD-level understanding of the subject, how am I to know which of them is right?

The problem is that when you’re not an expert, you need to defer to the experts, but you can’t always know who the experts really are without yourself being one. If two people show up and tell you they are doctors, and each says the other is a quack and a fraud, what test will you use to figure out which one is the quack? We know that throughout history, plenty of the people in any society who were looked to as authorities turned out to be completely wrong. Should the average person have listened to them or ignored them? It’s a very serious dilemma, one that is not easy to resolve.

In practice, people end up believing strongly in a lot of things they only half-understand, because they’ve heard it from a person they trust. You’ve probably seen this happen many, many times during the COVID-19 pandemic. You’ll hear one person say that masks don’t work. Another person will say that of course masks work, there are studies. The first person will say that a doctor told them that the studies are badly done, and the Surgeon General said masks aren’t effective. Or how about vaccines? Just recently, I overheard a conversation in a coffee shop that went like this:

Person 1: I’m not going to take a vaccine, they’re saying they don’t know if it’s safe.

Person 2: I’ll take a vaccine, but Fauci says it has to be done properly, I’ll believe it’s safe when he says it’s safe.

Person 1: I don’t know about Fauci, he said we didn’t need to worry about the virus to begin with. [True.]

People have to figure out who they can trust, and it’s not easy, especially when lots of frauds are trying to pass themselves off as experts, so a lot of arguments between people are about who to trust and what grounds we have for trusting them. In this magazine, I have shown how many highly-credentialed and widely-cited people (psychologists, philosophers, economists, legal scholars, and computer scientists) can make completely bogus arguments that often look superficially reasonable. An “environmentalist” whose book is put out by a major mainstream publisher will turn out to be distorting basic climate science research. A podcaster dubbed “the cool kids’ philosopher” by the respectable New York Times will turn out to be dishonest and ignorant. The respectable New York Times itself will publish totally misleading propaganda and treat undemocratic autocrats as the saviors of democracy. A Nobel Prize-winning president who appears brilliant and inspiring will turn out to be oblivious and vacuous. A smiling, charming vice president will turn out to be a serial liar. Expert pollsters will turn out to be making stuff up as they go along, witty, debonair public intellectuals will turn out to be racists who don’t have a clue what they’re talking about, astute, prize-winning reporters will use utterly distorted facts in support of dubious theses, and professional-looking think tanks will turn out to be completely untrustworthy.

Personally, I am sympathetic to people who end up believing things that are very wrong, because I know how huge a task it is to sift through the barrage of information we receive and pick out what’s right and what’s not. (Worse still, some of the most reliable scholarly material is extremely difficult and expensive to access.) I’m on the left, but I actually get why there are people who trust Donald Trump. Trump lies constantly, but so does Biden. Fox News often pushes dishonest nonsense, but so does the nation’s Paper of Record. Often everybody on either side of a dispute is making claims they can’t support. (Critics of the New York Times’ “1619 Project,” for instance, are frequently wrong (and the project itself is very valuable), but the project’s creators, too, have not been scrupulous. The New York Post’s reporting on Hunter Biden’s emails appears to have been poorly fact-checked, but so were claims that the Post’s reporting is “Russian disinformation.”) Never assume that just because one side of a dispute is wrong, the other side is right. Everyone could be wrong.

This does not mean that some sources are not relatively more reliable. The New York Times is not Natural News. The Wall Street Journal is not InfoWars. It does mean, however, that you can be misled wherever you go, that true words can be spoken on Fox and false ones by winners of the Pulitzer Prize. We can’t be so cynical as to write off “the news” as too biased and untrustworthy to bother trying to parse, because ignorance of the world around us is also not an option. What we have to do is be vigilant and learn critical thinking, to demand that claims be substantiated and examine the evidence and arguments for ourselves. When we see a headline accusing a foreign country of doing something nefarious, we need to think about what it is they’re being accused of doing, who is making the accusation, and whether it holds up. From World War I to the Iraq War, the American public has been led to support horrific foreign policy blunders by treating the words of its government and its newspapers as if they are true, so we have an moral obligation to become “intellectual anarchists”: demand that every authority justify itself before you accept it.

“I can’t tell when you’re telling the truth.”

“I’m not.”

“How do I know anything you’ve said is…”

“You don’t.”

—Frank Zappa, Uncle Meat

The right-wing video website PragerU has been phenomenally successful at getting millions upon millions of people to watch its 5-minute videos on political and economic subjects. Their videos are slick and professional, and hosted by charismatic pundits. They present themselves as offering pure factual information, and include links to sources so that you can check whether what they say is true. They may well appear trustworthy if you don’t know anything about them (you might even assume they are an actual university, which they are not—this alone borders on fraud). But they’re propaganda. They are not just “conservative.” They are trying to take the world as it actually is and filter it in a way that will give you a completely wrong and false understanding of what things are really like and what is going on. They are fucking with your head, psychologically manipulating you through extremely clever tactics.

That’s why it’s so insidious that PragerU is now infiltrating public schools, encouraging teachers to use their videos in the classroom as part of their ongoing project to slowly turn millennials conservative. Teachers are not necessarily explaining to students that they should be extremely wary of every single claim they hear in a PragerU video; the Huffington Post reported that students in one school were simply being told to watch the videos and summarize their points. There is research showing that just being exposed to a point of view in the media can make one more likely to believe it, because we tend to trust things we read. So it’s quite likely that putting PragerU videos in schools will indeed turn students at least a bit more conservative, if the videos aren’t contextualized and presented as part of an exercise in studying different types of propaganda.

It’s very important, then, that high school students learn how to think critically and demolish bad talking points. There is an extremely well-funded conservative effort to mold young minds, and because the left doesn’t have any money to counteract that effort, we rely on having sharp and engaged thinkers. Learn how to spot manipulation so that you can keep yourself from being manipulated—resisting this is a “putting your own mask on first” exercise—and then help others avoid being hoodwinked.

To see how this is done, let’s look at four recent PragerU videos (they were the four most recent at the time I started writing this, though since the site adds new videos frequently they are no longer) and see how they make their cases, why they’re persuasive, and how to figure out that they’re wrong.

1. Free the Freelancers

In this video, Patrice Onwuka of the Independent Women’s Forum discusses legislative pushes to give workers currently classified as “freelancers” access to employment benefits like healthcare and paid time off. She focuses on California’s controversial Assembly Bill 5, which required companies to treat workers as employees (and pay minimum wages and benefits) if the work the workers do is part of the company’s core business and the company exerts certain kinds of control over the worker. The law was passed in an effort to prevent companies from “misclassifying” employees as contractors in order to get out of their legal wage and benefit obligations, but some large “gig economy” companies have refused to abide by it. Uber, Lyft, DoorDash and others then spent hundreds of millions of dollars to ensure the passage of Proposition 22, which now explicitly exempts them from the law. (DoorDash gave restaurants millions of “Yes on Prop 22” bags and Uber deluged California drivers with pro-Prop 22 messages.)

Onwuka says the issue here is “freedom.” (When you hear the word “freedom” used to justify something, the siren on your Euphemism Detector should immediately start blaring. It’s not that freedom isn’t important or real, but that it’s a very easy word to throw around in support of things that don’t necessarily look much like freedom at all.) Onwuka says Assembly Bill 5 came about in part because of the “influence the unions have over California politics.” She says that it will lead to “fewer jobs and fewer people employed,” and that it was “authored by a former union boss,” assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez. “They love their freedom,” Onwuka says of freelance workers, citing numerous statistics showing that freelance workers enjoy not having a boss, getting to set their own hours, and do not want to return to traditional employment relationships. She says that without the “flexibility” that Uber and Lyft drivers currently enjoy, there will be fewer jobs, higher prices, and fewer cars available for customers. She concludes that “flexibility, freedom, and opportunity is the bright future of the American worker unless policies like AB5 get in the way.”

How should we evaluate Onwuka’s argument? First, let’s note that we know Onwuka is not fair-minded, because she does not give a chance for the supporters of the bill to make their case in their own words. She plucks a single controversial quote by assemblywoman Gonzalez—she said these freelance gigs weren’t “good jobs” and elsewhere called them “feudalism”—who is described as an ex “union boss” (subtle choices of descriptor are made to influence your perception). Of course, it’s not surprising that there are a bunch of polls showing that freelancers like being their own boss—I wouldn’t want to have a real job, either; jobs suck, bosses suck. The real question, which is not asked, is: how many freelancers, if you ask them, believe they should be provided with healthcare benefits, paid sick time, and a minimum wage? You should be very suspicious that poll results on the question “do you like being free to choose your hours” were reported, but poll results on the question “do you want basic employment rights” were not.

In the “facts and sources” section, Onwuka’s claim that hundreds of thousands of jobs will be lost links to a site called “Labor Pains: Because Being In A Union Can Be Painful.” According to the site:

A new report from the Berkeley Research Group found that “forcing app-based delivery and rideshare drivers to become employees would result in eliminating 900,000 jobs, reducing the number of drivers needed in California by 80 to 90 percent.”

Losing 90 percent of all rideshare drivers would be huge. How on earth did the Berkeley Research Group (neutral-sounding organization) come up with this number? If you click the link, you will be taken to a very brief summary of the BRG’s findings. It says that “based on the latest available data prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, requiring drivers to become full-time employees will reduce the number of needed drivers from more than 1,000,000 to less than 100,000.” But how do we know this is true? How did they calculate it? The report tells us that increased labor costs will result in increased prices, which will result in lower usage of the services. But why do they believe 90% of drivers will lose their jobs? All the summary says is that this is “the results of our in-depth research and economic modeling.” But what research? What modeling? The summary tells us nothing.

I was curious to see if I could find out where this extremely high number was coming from. I found a press release on the industry-funded “Yes on 22” page touting the Berkeley Research Group analysis. It, too, only contained a link to the summary, not to the actual report. But it contained contact information, so I emailed Yes on 22’s press person as well as one of the authors of the report. I asked how I could find the actual report, not just a summary listing its conclusions. The Yes on 22 person said I should talk to the report co-author, William Hamm. The report author said I should talk to the Yes on 22 person. The Yes on 22 person then offered to arrange a call with Hamm.

Hamm and I spoke on the phone. Without my asking, he told me that while he was being paid by Yes on 22, his analysis was completely independent. This was interesting, because in the press release, it did not say that the research had been funded by the campaign (and thus by the industry). It was presented as if it was independent research. Pretty huge conflict of interest not to note.

I asked Hamm how he arrived at the conclusion that 90 percent of all rideshare jobs in California would be lost if AB5 was put in effect. He reiterated what is available in the report, that prices would go up as a result and jobs would be lost. This, of course, does not answer the question, and I asked him how specifically he estimated the change in demand for rideshare services that will occur. He said that in the report they use an estimate of “demand elasticity” from this report on rideshare economics by the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs. But while he gave me an account of the theory of how it would happen, he did not tell me the actual math that led him to conclude 90 percent of drivers would lose their jobs. Interestingly, he did say that by “drivers” he meant “anyone who did a ride for a rideshare app in a given year,” meaning that many of the drivers who would “lose their jobs” might have barely ever used the platforms.

But it wasn’t very easy to assess the claims being made without being able to scrutinize the actual model and figure out where the numbers were coming from, so I asked Hamm to send me the report. He refused, saying that the report was the property of the Yes on 22 campaign, for whom it had been prepared. So I replied to the Yes on 22 spokesperson and asked him for the report. I never heard back.

It is more than a little fishy that Yes on 22 has not disclosed more about how its paid consultant produced this exorbitant figure. We might suspect, though we cannot prove without seeing it, that the report is not very well done, and that its industry funding severely biased its results to come out in accordance with the message the industry wanted to send on Prop 22. Either way: surely nobody who wants to discuss these issues seriously can cite statistics whose origins are this murky. Without knowing methods, how are we supposed to know we are being told the truth? We’re supposed to trust that secret industry-funded research would never be biased toward industry-favored conclusions?

There’s a core lesson here for those who want to resist propaganda: always check sources. Examine them closely. Statistics do not pop out of thin air. They are created on the basis of data and methods, and they are only as good as the data fed into them and the methods used.

Unfortunately, there are problems with the existing legislative fixes for the problem of employers declining to pay benefits. Vox Media, which supported AB5, then laid off a bunch of freelancers, because it didn’t want to have to classify them as employees. Onwuka cites this as proof the bill is a bad idea, but it actually shows us what’s difficult about trying to regulate away the injustices endemic to capitalism. The right is not wrong that profit-seeking companies often respond to attempts to improve workers’ situations by screwing over workers in new ways. This is because companies do not operate in the interests of workers, but rather in the interests of owners. Freelancers may be frustrated that they lose work after legislation like this passes, but it’s important to understand that it’s the companies who do not want to give their workers what they are entitled to. This is why, however, it’s ultimately not possible to fix these problems without public or worker ownership.

Prop 22 passed, exempting Uber and Lyft from having to pay their workers the benefits that other companies have to pay. The massive spending campaign by the tech companies paid off. (It’s worth noting that if paid campaigns mold public opinion, and money is unequally distributed, democracy is inherently a sham.) We therefore don’t know what the economic consequences of treating rideshare drivers as workers would have been. But we will soon have lessons from elsewhere around the world: France, the United Kingdom, and Spain have required these companies to treat their workers as workers rather than contractors. We should watch these countries closely. If rideshare businesses survive and workers end up better off, then this will show that the arguments made by the companies are simply an effort to protect their bottom lines. Certainly, though, we can expect that PragerU will find every statistic it can to show that the reforms have “hurt the very people they are trying to help.”

2. They Say Scandinavia But They Mean Venezuela

In this video, commentator Debbie D’Souza (who was born in Venezuela) argues that contemporary socialists want to replicate Venezuela’s economic catastrophe in the United States, but dishonestly suggest that they want a Nordic-style social democracy instead. “The American left keeps telling us they want to take us to Stockholm,” D’Souza says, “but its policies point in the direction of Caracas.”

D’Souza’s video is much less sophisticated and persuasive than Onwuka’s, and thus does not need as much time spent on it. In fact, very little evidence is provided for her position. She does not quote socialists. She does not go through the Bernie Sanders 2020 platform and show that it corresponds to Nicolas Maduro’s legislative agenda. That’s because if she talked about the actual policies socialists are advocating (Medicare for All, a Green New Deal, paid family leave, workplace democracy), the Venezuela comparison would be laughable.

How does she do it, then? Well, there are a few familiar tricks that are pulled by conservatives when talking about Nordic countries. Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Denmark present difficulties for conservatives, because these countries are prosperous but also have “big government” programs and a strong welfare state, which destroys the conservative argument that “big government” kills the economy. (Norway, for instance, has far more public ownership than Venezuela!) Leftists like Bernie Sanders point to these countries to show that government-provided universal healthcare is not a pipe dream but a very feasible reality. D’Souza does not respond to that. Instead, she gives a common conservative talking point: actually, these countries are far more “capitalist” than Sanders will admit. This is because “most have private healthcare and education options,” they “don’t have a government-set minimum wage,” and it’s “easy to start a business.”

All of this is extremely misleading, and I’ve gone into more detail about why in a long review of a book on socialism by Dinesh D’Souza (who is married to Debbie D’Souza and makes similar arguments). They’re deliberately leaving out critical information. She doesn’t tell you that private schools are virtually nonexistent in Finland’s excellent education system. Or that the reason there are no minimum wages is that unions are so strong that minimum wages are unnecessary. Or that whether it is “easy to start a business” has nothing to do with socialism. She says these countries are “capitalist in wealth creation, socialist in wealth distribution,” without noting the huge role the state plays in the economy itself.

So D’Souza’s case only holds up because she selectively presents information calculated to mislead you. Why does she think socialists want America to look like “Venezuela”? Her only two arguments are that (1) in the Nordic countries, there are large Value Added Taxes, while the American left favors wealth and income taxes and (2) Venezuela introduced gun control. These are weak arguments. First, if the argument is that socialist policies will turn the American economy into the Venezuelan economy, gun control is essentially an irrelevant feature (Australia’s gun control policies are strict, too.) On taxes, it is hard to even grasp D’Souza’s point. The Nordic countries do indeed have higher wealth, income, and inheritance taxes than we do, not just a VAT. There is just no evidence whatsoever that more taxes create a Venezuela-style economic crisis. There is, however, evidence that social democratic policies are correlated with happiness.

3. How To Steal An Election: Mail-In Ballots

In this video, Eric Eggers of the Government Accountability Institute argues that mail-in balloting offers an opportunity for fraud and produces election results that cannot be trusted. This is an example of a video that uses a genuine issue to lead viewers to an erroneous conclusion, and may now have serious consequences for our democracy.

Eggers says that while absentee balloting (where voters must request a ballot) is fine, “universal mail-in balloting” (where ballots are sent out to all registered voters) is subject to a number of problems, and voters have “very good reasons to be concerned” about it. He says that “bureaucratic incompetence” will result in ballots not being counted, citing “serious snafus” in prior elections. For example, he says, in Wisconsin, more than 23,000 primary ballots were thrown out because they were not filled out correctly. Ballots have been mailed to voters who have died. In Virginia, approximately half a million absentee ballots were reportedly sent with some incorrect information. In Wisconsin, 1,600 ballots were found after the election, too late to be counted. Eggers cites New York Times reporting from 2012 that warned of possible problems with mail-in ballots:

“Votes cast by mail are less likely to be counted, more likely to be compromised and more likely to be contested than those cast in a voting booth… Election officials reject almost 2 percent of ballots cast by mail, double the rate for in-person voting… While fraud in voting by mail is far less common than innocent errors, it is vastly more prevalent than the in-person voting fraud that has attracted far more attention, election administrators say. There are, of course, significant advantages to voting by mail. It makes life easier for the harried, the disabled and the elderly. It is cheaper to administer, makes for shorter lines on election days and allows voters more time to think about ballots that list many races. By mailing ballots, those away from home can vote… [But v]oters in nursing homes can be subjected to subtle pressure, outright intimidation or fraud. The secrecy of their voting is easily compromised. And their ballots can be intercepted both coming and going.”

Eggers comments: “Under the best of circumstances, the bureaucracy struggles with mail in balloting. Under less than the best of circumstances, that’s not a scenario we want to face.” He says that there will be long delays in certifying a result and that “the longer it takes, the less legitimate an election seems.” The incidents he has cited are just “the mistakes we know about,” implying that there may be many others. He says there is “shoddy security” and implies (as in the title of the video) that the more mail-in ballots, the more likely an election is to be stolen.

It is important to draw a distinction here between the facts Eggers cites and the conclusions he draws from those facts. It is indeed the case, as the New York Times reported in 2012, that there are some unique difficulties with mail-in ballots. Getting ballots in the hands of the right people can be hard given how many move or die. Getting them all back in time is hard. When voters have to fill out forms themselves, they are likely to make errors. When there is no guarantee of a “secret ballot” in a voting booth, people may be subject to pressure on how to vote by their employers or their families. Sometimes ballots get lost completely. In this election, there were plenty of ballots that did not get to their destination on time, in part seemingly because of negligence by the USPS.

But there are, as the New York Times notes (and Eggers chooses not to), significant upsides. Mail-in ballots also make voting much more accessible. During a pandemic, there may be reasons that we are okay with making the trade-off of having ballots take longer to collect and count. It’s true that if you want to make sure your vote counts, you should probably vote in person, because mail-in ballots are more likely to be rejected (although note that in that Times story it’s a 2 percent rejection rate versus 1 percent).

Eggers takes the evidence that there are logistical problems with mail-in balloting and uses this to imply that we fundamentally should not trust the results of mail-in elections, and even that they are likely to be stolen. This cannot be concluded from the facts provided. The idea that if it takes a long time to count the ballots, the election “seems less legitimate” is Eggers’ conclusion, but it’s not one we have to draw. He cites the 2000 election as an example. But the 2000 election wasn’t illegitimate because it took a long time to figure out who won. It was illegitimate because they didn’t conduct a full and fair recount, meaning that the wrong guy was probably given the presidency. Legitimacy is assured not by being quick, but by being careful.

Essentially, Eggers is using the fact that bureaucracies have problems sometimes to lead us to the conclusion that there are probably far more problems than we know about and the election will probably be stolen. But we need to keep these ideas distinct. The line “these are only the problems we know about” invites us to speculate wildly, but we shouldn’t. We should speculate only on the basis of what seems likely. (One reason a conspiracy to steal an election doesn’t seem very likely is that it would take a highly coordinated, secretive, and professional effort to assume the identities of many thousands of voters, and elected officials are barely competent enough to run their own campaigns, let alone pull off highly skilled acts of fraud.)

What Eggers is doing is not helping us rationally understand the issues with contemporary American elections. Instead, he is just sowing unsubstantiated doubts based on whatever instances he can find (a pet once got a ballot!) so that if Donald Trump loses, he can more effectively argue that the election was probably stolen. If Eggers was trying to rationally evaluate the chances of an election being stolen, he would discuss what would be necessary in order for something like this to happen. But saying “well, we don’t know, could be worse than we think!” is just a way of undermining people’s confidence in their democracy without justification.

4. Where Do You Want To Live: Red State or Blue State

FreedomWorks economist Stephen Moore argues in this video that “red state America is prospering, and blue state America is in meltdown.” He argues that there is an exodus from majority-Democratic states to majority-Republican states. Red states, he says, offer “low taxes, light regulation, tough-on-crime policing, and worker freedom” while blue states are characterized by “high taxes, heavy regulation, high minimum wages, and mandatory union membership.” Moore makes four central points:

- States like California, Illinois, and New York are losing population while states like Florida, Texas, and Tennessee are gaining residents.

- Red states have low taxes and your money goes further—he cites a study showing that $100 has $111 of purchasing power in Tennessee and only $89 in New Jersey.

- The cities with the highest murder rates have Democratic mayors, and there has been unrest in Democratic-run cities like Portland and Seattle.

- Blue states have had the most serious coronavirus outbreaks, and a New Yorker was far more likely to die of the disease than someone who lived in Texas. [Since the video was made, red state COVID-19 deaths have massively shot up and now ⅔ of deaths are in red states.]

Let’s first notice something a bit peculiar. I think comparing “blue states” and “red states” is a bit of a silly exercise, especially because as a leftist I am almost equally cynical about Andrew Cuomo as Ron DeSantis. But if we did want to do this, wouldn’t the first thing to do be to look at statistics on poverty, health, longevity, school quality, air/water quality, and levels of life satisfaction? Why do you think Moore doesn’t talk about those things? Aren’t they the first place to start a comparison?

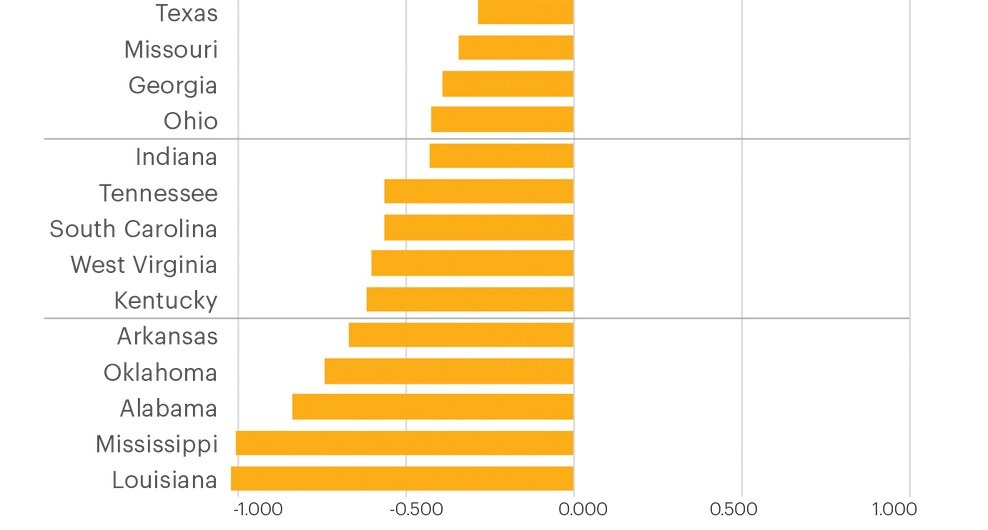

Well, I think you know why Moore doesn’t talk about those, and it’s because the most severe poverty, the worst schools, the slowest recovery from the recession, the poorest health, and the worst environmental quality is in Republican-voting states. The top 5 states with the best school systems? Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Vermont. The wealthiest states? Maryland, New Jersey, and Hawaii. The poorest? West Virginia, Mississippi and Arkansas. The states with the worst health outcomes in the country? Look:

Now, I am not trying to do the obnoxious blue state thing of treating the South as backward and poor and deserving of its fate. What I am pointing out is that Stephen Moore is manipulating you by choosing only the statistics that make red states look like great places to live and ignoring the ones that do not make them look good.

This is an important example of how you can “lie without saying anything false.” Moore’s statistics are not wrong. He cites reputable sources to show that people in the blue states pay more state taxes. But he chooses not to reveal that people actually get something for their tax dollars: better public health programs, better schools, better pollution control.

What about the exodus? Well, it’s complicated. About as many New Yorkers moved to New Jersey, Pennsylvania, California, and Connecticut as to Texas, Florida, and North Carolina. And more Californians move to Washington or Oregon than move to Texas. It’s not so much that they’re fleeing to red states as that they’re fleeing to more affordable places with less density. The cost of living in New York City and California is high, in part because so many people want to live in these places and those people tend to be wealthy, which squeezes people out. Imagine if there was an exclusive club that had an extremely long line to get in. The proprietor of a comparatively empty, less luxurious club next door might start seeing people flee the line, but it would be a bit shameless for that proprietor to say “Ah, see, the fact that people are choosing my club over the popular club proves they no longer want to go to it.”

Again, I should emphasize: I am not saying California and New York are better than Texas or Louisiana. I personally would much rather live in Texas or Louisiana, though it is in spite of their right-wing policies rather than because of them. (I would gladly pay more in taxes for some better infrastructure.) The point here is only that Stephen Moore presents himself as telling you about a trend and showing you some statistical facts, but he is distorting reality through presenting it selectively.

As for violent crime: you could very easily cherry-pick different statistics that tell a different story. The three states with the lowest violent crime rates in the country are Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire. Louisiana, Arkansas, and Alabama, on the other hand, have extremely high crime rates. (As for coronavirus, as I say, I’m not going to defend Andrew Cuomo, but Republican leaders have consistently treated basic public health measures as as unacceptable intrusions on American freedom, and I’d just note that communist governments in Cuba and Vietnam have had under 200 COVID-19 deaths between them rather than over 200,000.)

Vermont, by the way, does fantastically on quality-of-life metrics, so if we’re going by correlations, (aka if we’re using Moore’s standards), those states with politics that tend toward Bernie Sanders-style socialism clearly end up being the best governed. In fact, set aside U.S. states and look at countries around the world, and you’ll find that those who have more of the policies favored by socialists (workplace democracy, the public provision of goods and services, strong trade unions, political democracy) tend to score better on a variety of important measurements of social success.

Now, the real world tends to be complicated, and the story isn’t as simple as “Democrats good, Republicans bad.” But you need to see how facts can be selected and omitted in order to tell a story that supports the speaker’s ideological preconceptions. I can do that, and so can Moore.

We have seen, then, how an argument can be made for a position that uses real, reputable facts and sources but is actually “propaganda,” by which I mean that it cares more about persuading you to hold a political position than about giving you an accurate understanding of reality. We saw Onwuka decline to present the other side’s case and throw out iffy statistics produced by the very people whose economic interests are at stake. We saw D’Souza leave out critical information about the nature of Nordic governments, and decline to explain what the American left’s actual policy positions are. We saw Eggers take legitimate logistical difficulties that come with running elections and use this to try to raise the worry that we should doubt any result even if we have no evidence of fraud or misconduct. And we saw Moore ignore the success of social democracies around the world, and instead pick and choose his favorite things about red states in order to bury all the icky stuff about poverty, bad health, and poor schools.

Hopefully you see, then, how this stuff works. It’s a bit like magic tricks: what appears to be the case is not what is actually the case, and the “magician” (in this case, the pundit) is pulling careful maneuvers to make sure you do not see what they are doing in order to mislead you.

Let’s note, too, that there are all kinds of deft little touches that help to create the veneer of credibility. Onwuka is from the “Independent Women’s Forum” and Eggers is from the “Government Accountability Institute.” These organizations sound neutral, but they are actually right-wing; the IWF was originally formed to defend Clarence Thomas from sexual harassment charges and the GAI was founded by Steve Bannon and is closely associated with Breitbart. Moore presents himself as a mere “economist” but when you look him up, you’ll find that he has a record of making positively deranged statements on climate change (suggesting that climate change is a “scam” pushed by climate scientists as part of a conspiracy to obtain research grant money).

Always carefully look up the experts you are hearing from, then. Scrutinize their records. Scrutinize their organizations. They will often come from organizations with benign-sounding names that suggest trustworthiness and objectivity. (Say, for example, “Current Affairs.”) You need to use your judgment and be very careful.

What can you do about the problem of expertise? It’s not always possible to evaluate a study to determine whether it has been well-conducted. You’re going to have to trust that certain experts know what they’re talking about on matters where you are simply less informed than them. What you need to do is try to test whether the experts appear to be honest and forthright, by looking closely at the parts of what they say that you do understand and seeing whether they hold up.

For example: I was not in a position to evaluate whether the Prop 22 job loss study’s numbers were valid. I am not an economist, and I did not have access to the data or methods. But even as a layperson I could notice a few things: first, the study was funded by Uber, DoorDash, Lyft, and others. The researcher they hired was “independent” but he admitted to me that he had been paid by the campaign. We know that the tobacco industry funded “independent” researchers to sow doubt about the health consequences of smoking cigarettes. So we should be wary about industry-funded research.

This is not because we should be “conspiracy theorists.” It’s because of a basic economic fact: a corporation has a strong incentive, in fact arguably an obligation, to lie. Free market economist Milton Friedman said that the only “social responsibility” a business has is to increase its profits. Well, a tobacco company’s profits come from cigarettes. If the industry has reason to believe that if cigarettes are understood to be mass killers, they will be regulated, then under Friedman’s framework, the industry has a social obligation to do whatever it can to distort public perception. Not only is it not bad to hire fake experts and smear real scientific researchers, but it has an obligation to do so! This is why the fossil fuel industry has worked so hard to throw doubt on climate science. If the public understood the climate consequences of fossil fuel use, vast amounts of oil might have to be left in the ground, a massive financial loss for the companies. It is thus their duty to try to trick us.

I recently interviewed former Cigna insurance company executive Wendell Potter, who said that the major health insurance companies deliberately tried to mislead the public about the quality of healthcare systems in other countries. They didn’t do this because they have an intrinsic desire to make Americans unaware of how much worse their healthcare is and thus suffer unnecessarily. They did it because they work for companies whose profits depend on the maintenance of the system in its current form, and thus it is their job to proactively try to make sure nothing happens to destroy that system. Potter was very blunt about what the companies do and the way that amoral profit-seeking is used to justify outright mendacity:

I know how much money is spent to hire PR firms to work with linguists, to work with a lot of different people to come up with just the right words and phrases to manipulate public opinion and to come up with campaigns that are designed to scare people away from any kinds of proposals to create a system that’s not like ours…. the work that my colleagues and I did was to really make the term “single-payer,” for example, very toxic so that Democrats in Congress would shy away from it… .you know that if you want to get a bonus, if you want to get stock options, if you want to get a raise, you have to impress your superiors, you have to do your part to help the company achieve its ultimate objective, which is to meet Wall Street’s profit expectations.

Of course, the fact that something comes out of a CEO’s mouth doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s false. It means only that we should be suspicious, because if the truth was ever something that contradicted their self-interest, it would be their job not to tell us the truth. So, for example, the restaurant industry always says that increasing the minimum wage will have devastating effects on employment, regardless of whether this is true or not. Theoretically, Uber and Lyft are far more likely to launch a publicity campaign insisting a piece of legislation will hurt their employees if the legislation would hurt their shareholders than if it would hurt their employees, because it is their shareholders whose interests matter to the company’s executives. Albert Hirschman, in The Rhetoric of Reaction, pointed out that for hundreds of years, conservatives have always argued that any given social reform is going to fail and hurt people, and that they say this regardless of whether it has any factual basis, because their opposition to social reform is not empirically grounded. That doesn’t mean they’re wrong (a regulation could result in fewer jobs) but that we have to investigate the question carefully before accepting their arguments.

We should therefore be suspicious of the Prop 22 study because we understand the interests that produced it. We should grow more suspicious when the makers of the study decline to release detailed information about the methods or data, preventing us from evaluating how its shocking headline statistic was arrived at. After all, if the number wasn’t obtained through dubious and biased methods, why wouldn’t they show us how it was produced? That would, after all, make it far more persuasive. And if they are interested in persuading us, and believe their number is accurate, surely they would want to give us the tools to independently evaluate it.

So sometimes you are not able to check whether a source is accurate or not, but you can check whether it can be trusted. Eric Eggers, the vote by mail guy, was quoted in a story about voter fraud saying that 170 Ohio voters in one Congressional district had their birthdates listed as either 1900 or 1800. The Cincinnati Enquirer looked into the matter and found that before 1974, the state didn’t require voters to list their birthdate, and those voters had their birthdates entered automatically as 1800 or 1900. Eggers, responding to the Enquirer, said “Why voter rolls are inaccurate is irrelevant… The point is that they are inaccurate.” But Eggers was trying to give people the impression that this inaccuracy should cause people to suspect fraud. Of course it matters why the rolls are technically inaccurate. If the explanation is a harmless one, Eggers is creating suspicion for no reason.

Eggers, then, is seizing on small, explicable, unavoidable discrepancies in order to call entire elections ino question. This shows he is not honest and can’t be trusted. One important point to remember is that you only need to catch someone once not being forthright in order to call all their other assertions into question. For example, environmental commentator Michael Shellenberger wrote a book arguing that many claims of climate activists are wrong and exaggerated. I haven’t finished the book yet, but I have already found Shellenberger telling a huge whopper about climate science, insisting that California’s wildfires have nothing to do with climate change when this is false. The fact we’ve seen him willing to tell even one egregious lie makes his entire book untrustworthy, and means nobody should believe a word of it until they’ve checked all his sources and independently verified every statement.

So: you need to look closely. Oftentimes, it is not obvious at first why something is wrong. You have to think about it for a while to spot the sophistry (arguments that sound reasonable but are actually deceptive and fallacious). Do not assume that just because you can’t come up with a good answer to a point right now, it must be correct. Be a skeptic.

The world does not get better unless people work to make it better, and they can’t do that unless they know what is real and escape from dangerous delusions. We have a moral responsibility to be intelligent. Look at the footnotes. Follow them and see where they go. Find out how people can lie with statistics and then teach yourself to spot the tricks in the wild. And always remember that nobody is too smart to end up believing something stupid—not even you.