The Chomsky Position On Voting

It’s important to vote Democratic, but we should be under no illusions that voting Democratic will save us. Voting is a small part of our political lives.

Joe Biden is not a leftist. He has made this clear on multiple occasions; as a senator, he proudly self-identified as one of the most conservative Democrats; in his presidential campaign, he has explicitly stated that he rejects socialism; recently, he has repeatedly refused to endorse social democratic policies like Medicare For All and the urgently-needed Green New Deal. In the past year, Biden has shown little interest in courting the “Sanders wing” of the Democratic party, and I have documented at great length his dismal record and personal flaws.

Unfortunately, however, since Joe Biden won the primary, the only alternative to another four years of Donald Trump is a Biden presidency. Because another Trump term would cause so much human harm—the rapid acceleration of climate catastrophe, new ways of systematically brutalizing immigrants, a drive toward outright authoritarian measures of repression, escalation of the global nuclear threat, and the further takeover of the courts by an army of young right-wing judges—a Biden presidency has become urgently necessary. This is not because Biden himself is going to be an effective and progressive president, but because a Biden presidency is 1) an alternative to outright disaster 2) a precondition, a foundation, for necessary political changes.

It is obvious, then, that getting Joe Biden elected is important for the left, for reasons that have nothing whatsoever to do with Biden’s own politics. If Donald Trump is reelected, the chance of serious climate action dwindles to nothing, while there is at least a chance of compelling Biden to actually act on his climate platform. It will not be easy. At every turn the Democratic Party will try to compromise and take measures that are symbolic rather than substantive. But there is a conceivable strategy.

Understandably, many leftists are not terribly pleased by the prospect of having to vote for Joe Biden, a man who has shown contempt for them and their values, and has a documented history of predatory behavior towards women. But when voting is considered in terms of its consequences rather than as an expressive act, our personal opinions of Joe Biden become essentially irrelevant. If, under the circumstances we find ourselves in, a Biden presidency is a precondition for any form of left political success, and there are no other options, then we must try to bring it about. As Adolph Reed noted in 2016, “the overriding electoral objective now should be to maintain or expand political space for organizing, and a Trump presidency and Republican Congress would almost certainly undercut that objective in multiple ways, including intensified attacks on the rights of workers and the political power of their unions, on public goods and services, civil rights and liberties.” So “the primary national electoral objective for this November has to be defeating Trump. Period.”

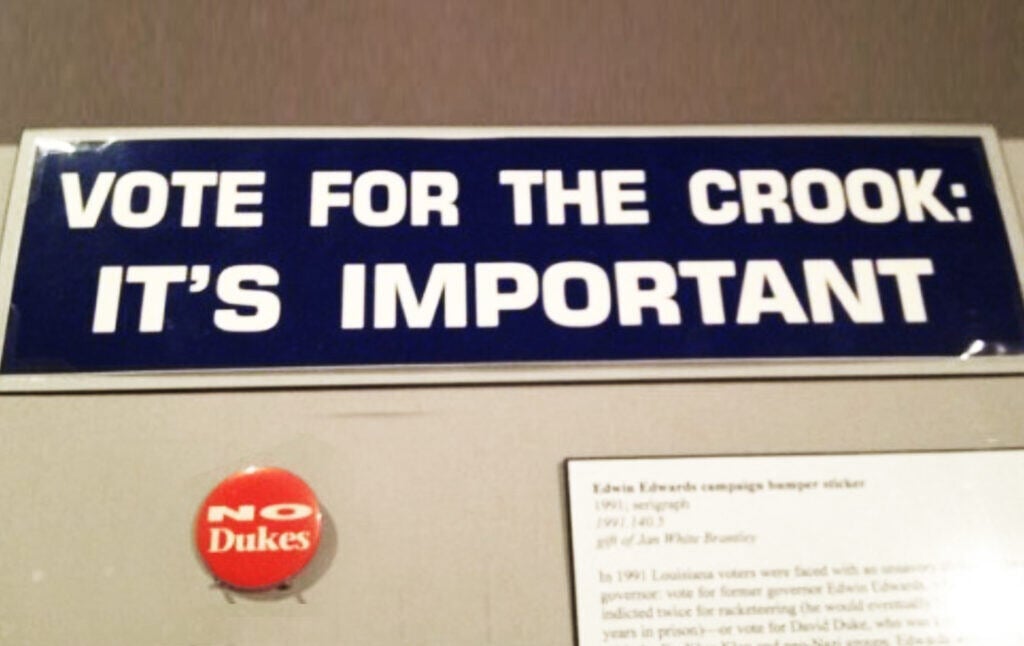

Reed used an illuminating comparison to explain why it was so important in 2016 to vote for Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump. In the 1991 Louisiana gubernatorial primary, the Republican candidate was former KKK Grand Wizard David Duke. The Democratic candidate was the infamously corrupt Edwin Edwards, who would ultimately end his career in prison on charges of racketeering, extortion, money laundering, mail fraud, and wire fraud. It’s hard to imagine anyone you could possibly trust less in public office than Edwin Edwards… except David Duke.

In that election, awful as the choices were, it was necessary to support Edwards. Bumper stickers read “Vote For The Crook: It’s Important.” Even incumbent Republican governor Buddy Roemer, who had originally been elected on an “Anyone But Edwards” platform, eventually endorsed Edwards. The priority of any sensible person, of course, was to keep an outright white supremacist from becoming the governor, and thankfully, Edwards did win, becoming the longest-serving governor in Louisiana history before ending up in the federal penitentiary. Reed used this example to show why voting for Clinton was so necessary in a race against Donald Trump, regardless of Clinton’s long record of terrible policies. “Vote for the lying neoliberal warmonger,” Reed said. “It’s important.” He, and many other famous leftists like Angela Davis, Noam Chomsky, and Cornel West, are saying the same thing this time around. “An anti-fascist vote for Biden is in no way an affirmation of Neoliberal politics,” West commented.

Some people on the left find this argument very difficult to stomach, though. In a recent conversation on the Bad Faith podcast, Briahna Joy Gray and Virgil Texas debated Chomsky about his stance. Gray and Texas voiced some common and understandable criticisms of the position. In response to the “vote Biden to stop Trump” argument, they and others ask questions like the following:

But if we are willing to vote for the Democrat no matter how awful they are, what incentive will the Democratic party have to ever get better? How are we ever going to get better candidates if we don’t have some standards? Is there really no one we wouldn’t support, if they were the “lesser evil”? Isn’t supporting “the lesser of two evils” still supporting evil? Why should I help someone get into office who has shown no willingness to support my policies, who feels entitled to my vote, who is not going to do anything to woo me? Surely I should make some demands of this person rather than indicating I will vote for them unconditionally. If you announce at the outset of a negotiation that you’re going to give the person what they want no matter what, you lose any power you have to influence them.

(Gray elaborates some of the points in “In Defense of Litmus Tests,” published in this magazine’s May-June issue.)

I’ll dive a little deeper into the particular conversation that Gray and Texas had with Chomsky shortly—how I think common ground can be found, and why it wasn’t. But to give my own response to these questions, let me say that while they are important, they can also seem strange if we examine how they would sound in other contexts. After all, think back to David Duke in 1991. Or the German election of 1932. Would it have seemed reasonable, faced with a Klan governorship, to ask: “But if I vote for Edwards, won’t I be incentivizing corruption? Isn’t the lesser evil still evil? Shouldn’t I demand Edwards stop being corrupt before I give him my vote?” The answers to these questions are: (1) maybe, but it doesn’t matter in the situation we’re currently in (2) yes (3) no, because if he declines to stop being corrupt, you’re still going to have to give him your vote, because the alternative is putting a Klansman in office, and “do unlikely thing X or I will help white supremacists win, or at least not work to stop them” is an insane threat to make.

The easy way to avoid being troubled by having to vote for people you loathe is to give less importance to the act of voting itself. Don’t treat voting as an expression of your deepest and truest values. Don’t let the decision about who to vote for be an agonizing moral question. Just look at the question of which outcome out of the ones available would be marginally more favorable, and vote to bring about that outcome. That doesn’t necessarily mean “Vote Blue No Matter Who” (if the Democrats had nominated David Duke, you might have to vote for some awful Republican). It just means: if faced with two bad candidates, forget for the moment about the virtues of the candidates themselves and look only at the consequences for the issues you care about. (This means that living in a swing state, where the potential consequences of a Trump win are much higher, makes the imperative to vote Democratic much greater than if you live in a state with an essentially foreordained outcome.)

Voting can have immensely important consequences—the narrow 2000 election put a warmongering lunatic in power and resulted in a colossal amount of unnecessary human suffering. But “the vote” itself is only a small part of our political activity and we shouldn’t spend too much time obsessing over it. The mainstream (I would call it “propagandistic”) view of political participation is that you participate in politics through voting. But instead, we’re better off thinking of voting as a harm-reduction chore we have to do every few years. (Reed compares it to cleaning the toilet—not pleasant but if you don’t hold your nose and get on with it the long-term consequences will be unbearable.) Most of our political energy should be focused elsewhere.

It’s also a mistake to think that the decision about whether or not to vote for Democrats in a general election can operate as an effective form of political pressure on Democrats. The mainstream Democratic Party does not see losing elections as a sign that it needs to do more to excite its left flank. John Kerry did not look at the 2000 election and think “My God, I need to work hard to appeal to Nader voters.” Hillary Clinton does not seem to regret choosing Tim Kaine instead of Bernie Sanders as her VP, even though that single decision may have made the difference between her winning and losing (along with a host of other factors). If Joe Biden loses this election, then assuming this country still has elections in four years, I guarantee you that centrists in the Democratic Party are not going to change their contemptuous attitude toward the left. One often gets the sense they are more interested in having someone to blame when they lose than in winning.

In my view, what is wrong with the position that “if you don’t threaten to withhold your vote, you will be stuck with a never-ending stream of bad candidates” is that it overemphasizes the role of “deciding who to vote for in the general election” as a tool of politics. One way to get better Democrats in general elections is to run better candidates and win primaries. Another would be to build an actually powerful left with the ability to coordinate mass direct action and shape the political landscape (and push to replace our system entirely if the opportunity arises). Publicly refusing to vote for Joe Biden in the general is not going to pressure him to debut Medicare For All as an October Surprise. We’re stuck with what we’ve got. That does not mean we’re stuck forever: Bernie still did very well in 2016 and 2020, and progressive candidates have been winning surprising victories in races around the country. But the general election vote itself is not how we effectively exercise pressure, in part because it would be unconscionable to actually go through with anything that made Donald Trump’s win more probable. The threat not to vote for Biden is either an empty one (a bluff) or an indefensible one (because it’s threatening to set the world on fire).

Let’s look at how some of these issues were hashed out on Bad Faith. Gray and Texas were skeptical of the argument that Biden’s terribleness is irrelevant to the question of whether to vote for him, while Chomsky has long advocated the position that the left should obviously vote for corporate Democrats in general elections—his reasoning being that even small differences between the two major parties have massive potential human consequences. But Chomsky also adds that we cannot see voting for Democrats as an act that is going to change the world. We have to understand that while election outcomes can be hugely significant for many millions of people, voting is mostly a spectacle, and if we see “deciding who to vote for” as a major part of our political activity, we are not going to bring about any significant progress.

As should be clear by now, I share Chomsky’s position on this, and have not seen any persuasive argument against it. It seems like basic common sense to me: vote for the candidate who will do the least harm, but voting in itself is a trivial act compared with the revolutionary organizing we should be undertaking and we’re not going to get better candidates until we do things other than vote.

The conversation between Chomsky, Gray, and Texas frustrated everyone involved, as these conversations often do. Essentially, for most of the hour, Gray and Texas asked variations of the same question, and Chomsky offered variations of the same answer. They appeared to think he was ignoring the question and he appeared to think they were ignoring the answer. But it’s worth examining what they asked, and what he said in response, and evaluating the two sides’ arguments.

All three agreed on the urgency of climate change, the problems with capitalism, and the need for social democratic programs. But, Gray asked:

“Why are we in a situation where we’re constantly being asked to choose between two options neither of which get us where we need to go?… Why is it that Joe Biden and the Democrats more broadly are rejecting these programs and what does that mean for our ability to effect change down the line without doing something that’s more radical, and valuing our votes enough to withhold them at some point under some conditions?”

She also pointed out that many people have good reason to be disillusioned with the two-party system. It is difficult, she said, to get people to care about climate change when they already have such serious problems in their lives and see no prospect of a Biden presidency doing much to make that better. She cited the example of Black voters who stayed home in Wisconsin in 2016, not because they had any love for Trump, but because they correctly understood that neither party was offering them a positive agenda worth getting behind. She pointed out that people are unlikely to want to be “shamed” about this disillusionment, and asked why voters owed the party their vote when surely, the responsibility lies with the Democratic Party for failing to offer up a compelling platform.

Chomsky’s response to these questions is that they are both important (for us as leftists generally) and beside the point (as regards the November election). In deciding what to do about the election, it does not matter why Joe Biden rejects the progressive left, any more than it mattered how the Democratic Party selected a criminal like Edwin Edwards to represent it. “The question that is on the ballot on November third,” as Chomsky said, is the reelection of Donald Trump. It is a simple up or down: do we want Trump to remain or do we want to get rid of him? If we do not vote for Biden, we are increasing Trump’s chances of winning. Saying that we will “withhold our vote” if Biden does not become more progressive, Chomsky says, amounts to saying “if you don’t put Medicare For All on your platform, I’m going to vote for Trump… If I don’t get what I want, I’m going to help the worst possible candidate into office—I think that’s crazy.”

Asking why Biden offers nothing that challenges the status quo is, Chomsky said, is tantamount to “asking why we live in a capitalist society that we’ve not been able to overthrow.” The reasons for the Democratic Party’s fealty to corporate interests have been extensively documented, but shifting the party is a long-term project of slowly taking back power within the party, and that project can’t be advanced by withholding one’s vote against Trump. In fact, because Trump’s reelection would mean “total cataclysm” for the climate, “all these other issues don’t arise” unless we defeat him. Chomsky emphasizes preventing the most catastrophic consequences of climate change as the central issue, and says that the difference between Trump and Biden on climate—one denies it outright and wants to destroy all progress made so far in slowing emissions, the other has an inadequate climate plan that aims for net-zero emissions by 2050—is significant enough to make electing Biden extremely important. This does not mean voting for Biden is a vote to solve the climate crisis; it means without Biden in office, there is no chance of solving the crisis.

Virgil Texas asked Chomsky why, if capitalism is causing ecological crises, “the real fight” isn’t against capitalist institutions rather than in favor of trying to push the Democratic Party toward reforms. The exchange went as follows:

TEXAS: If these capitalist institutions result in recurring ecological crisis, and existential ones, as they do, then isn’t the real fight against those institutions instead of a reform that maybe gets us over the hump in 30 years if it were possible to lobby those in power through activism, some kind of brokering, those who are beholden to the profit motive even if it destroys the environment?

CHOMSKY: Think for a second. Think about time scales. We have maybe a decade or two to deal with the environmental crisis. Is there the remotest chance that within a decade or two we’ll overthrow capitalism? It’s not even a dream, okay? So the point that you’re raising is basically irrelevant. Of course let’s work to try to overthrow capitalism. It’s not going to happen *snaps fingers* like that. There’s a lot of work involved. Meanwhile we have an imminent question: are we going to preserve the possibility for organized human society to survive? Are we going to preserve the possibility for us to work to overthrow capitalist institutions, or are we going to say “It’s hopeless, let’s quit.” I prefer the first. You’re calling for the second.

The important point here is that the question is not whether we attack capitalist institutions “instead of” reforms. The reforms are necessary in the short term; you fight like hell to force the ruling elite to stop destroying the earth as best you can even as you pursue larger long-term structural goals. What is true of climate is true of healthcare, too: obviously the ultimate goal in the United States would be a fully socialized medical system. Medicare For All is not such a system—it just socializes basic health insurance, not care. But it’s a step we must take because it’s within the realm of current political possibility. On climate, we are even more bound to working within the parameters of political reality, because there is an actual ticking clock and particular goals have to be met by particular times in order to minimize human suffering.

Gray and Texas note to Chomsky that for people who are struggling in their daily lives, climate may seem a somewhat abstract issue, and it may be hard to motivate them to get to the polls when the issue is something so detached from their daily reality. Chomsky replied that “as an activist, it is your job to make them care.” The point here is that the unimaginable suffering of future generations is something that people need to be made to give enough of a damn about to drag themselves to the polls, and because we have some faith that human beings, on average, tend to care a little bit about each other, the argument that preserving human civilization is a good thing should be able to be made persuasively. Admittedly, when people are dealing with the day-to-day challenges of economic immiseration and the resultant depression, it can be difficult to help them to imagine more long-term and seemingly abstract issues. None of this is easy.

This is part of why Chomsky argues that voting should be a relatively trivial part of one’s political life. It is, after all, mostly a spectacle. Take a few minutes, pull the lever, and return to activism and organizing. I don’t think he should have implied that voting is necessarily brief or easy and takes “10 minutes”—while the vast majority of people waited less than 30 minutes to vote in the last election, some waited hours, and the ones who do wait hours tend, as you’d sadly expect, to be poor people of color. There are already long lines for early voting around the country. That means that voting isn’t a completely trivial ask, at least not for everyone, but it’s still possible to say: even if voting involves a certain level of sacrifice and effort, the stakes of the election are clearly high enough to justify doing it. But the core argument here is still the same: we shouldn’t focus too much on voting or place too much faith in it. You do other political activities the vast majority of the time, and once in a while you go pull a lever.

Some have pointed out a tension in Chomsky’s position: on the one hand, he consistently describes voting as a relatively trivial act that we should not think too much about or spend much time on. On the other hand, he says the stakes of elections are incredibly high and that the future of “organized human life” and the fate of one’s grandchildren could depend on the outcome of the 2020 election. There’s no explicit contradiction between those two positions: voting can be extremely consequential, and it can be necessary to do it, but it can still be done (relatively) briefly and without much agonizing and deliberation. However, if the presidential election is so consequential, can we be justified in spending only the time on it that it takes to vote? Surely if we believe Trump imperils the future of Earth, we should not just be voting for Biden, but be phone-banking and knocking doors for him.

Well, I actually think it might well be true that we should be doing that, reluctant as I am to admit it. Climate change makes presidential elections increasingly consequential. The difference between, say, a 2nd Gerald Ford term and the Jimmy Carter presidency were not as large as one where Donald Trump is on the ballot and the window for climate action is closing. Likewise, a race with David Duke is vastly more urgent than a normal Louisiana gubernatorial race, and might morally require not just voting for Edwin Edwards but campaigning for him as well.

So, yes, it’s possible that even if the general rule is that presidential elections should occupy little of our time, in this election we should not just be voting for Biden but trying to get other people to as well. I actually asked Chomsky about this, and he said that he does believe it’s important to persuade as many people as possible, which is why at the age of 91 he is spending his time and energy trying to convince people to “vote against Trump” instead of sitting by a pool and hanging out with his grandkids. Note, though that that means the only serious debate is: is there a moral obligation to vote for Joe Biden, or is there a moral obligation to both vote for Joe Biden and campaign for Joe Biden?

No, I do not like that that is the question. I hate that that is the question. But here we are. We can ask other questions in a month, when this is over. Right now, the election predominates over everything else.

That fact explains one reason that Gray and Texas had such a frustrating time talking to Chomsky. They seemed exasperated that he kept repeating the same point about the election. After all, he admits that elections aren’t how you change the world, so why did he keep answering every question by referring to “the choice on November third”? Gray said at one point that we should assume most Bernie people would ultimately vote Biden, and wanted to know how we can fix the party if not by using the power to grant or withhold our votes.

There’s a reason Chomsky kept emphasizing next month’s choice in particular, though: right now, it is October. The November election is, right now, quite important. Once it is over, we are going to have one of two outcomes, and which outcome we get is going to be crucial in determining what we do next. Given that Trump’s reelection would be such a catastrophe, right now, at this point, it is worth spending an unusually significant amount of energy trying to prevent it, and to make sure people are all on the same page about the necessity of getting rid of Trump, so that we buy ourselves the time and space to do other political work.

But I think that Bad Faith’s listeners may have had a reasonable frustration: they want answers to the question: “Okay, but if we know Joe Biden won’t save us, what do we do instead? How do we embark on that long-term project of dismantling capitalist institutions? How are we going to pressure a Biden administration to move left? And if you shouldn’t focus on deciding who to vote for in a presidential election, what is an effective use of your time?”

This is where we must move decisively away from an obsession with the vote. Our task is to build independent left institutions, working class organizations, and social movements. How do we engage with Black and brown workers struggling to survive? We organize in the labor movement, and along the way we build the only working class institutions of real political consequence. We wage campaigns for community land trust housing or public housing. How do we break out of the seemingly ever-rightward drift of the political class? We build membership organizations with an explicit left orientation, like the DSA. We build independent left media organizations, like this magazine and a few other outlets, understanding the incredible power of the media in the process of the manufacture of consent. We take over stagnant conservative unions and member organizations, or found new activist organizations in their place, like the Sunrise Movement. More robust left movements exist outside the United States, such as the Landless Peasants Movement in Brazil and their heroic occupation of land and insistence on control of their own schools and institutions, or even European workers who wage mass strikes against centrist austerity.

Ultimately, any of the current or historical examples of organizing and social movement building will be unsatisfying because, as Chomsky points out, we have failed to overthrow global capitalism and continue to suffer under the rule of bosses. But one thing is evident: if we want to look toward electoral strategies for change, it had better be mass-based oppositional models like the Bernie campaign, not third-party protest candidacies or the threat of nonvoting. If we’re able to stage a revolution outside electoral means, we’ll need a more organized, radicalized, and aware public. And if electoral strategies do have a role to play, we’ll need to shift the balance of power and political landscape if we ever hope to win more than a handful of elections.

The question of how to win power does not have easy answers. What to do from now until November 3rd is, however, easy; what to do afterwards is much, much more complicated no matter who wins. But political activism is not an untested endeavor. We can study how social movements set goals and win them. We can look at examples of how power can be built steadily through mutual aid and how workers successfully unionize their companies. We can examine how activists are challenging water shut-offs in Detroit and how the Fight for 15 managed to get raises for millions upon millions of people across the country. We can look at how Sunrise activists successfully pressured Joe Biden to improve his climate platform (even if it doesn’t yet go far enough) and develop a plan for how to keep up that pressure, and the many other examples of the left successfully forcing politicians to adopt more progressive stances. We can learn from the Sanders campaign. We do not have to be hopeless, and we certainly can’t stop with getting Joe Biden elected, however necessary that might be.

Noam Chomsky’s view of electoral politics is, I believe, a sensible one. In fact, it’s not his; as he says, it’s the “traditional left view,” just one that we’ve lost clarity on. People mistakenly assume that by saying “vote against Trump,” Chomsky is putting too much stock in the power of voting and is insufficiently cynical about the Democratic Party. In fact, it’s completely the opposite: he puts very little stock in voting and is perhaps even more cynical about the Democrats than his critics, which is why he doesn’t think it’s surprising or interesting that Biden is offering the left almost nothing and the party is treating voters with contempt. The “traditional left view” he talks about is, roughly: we need to participate in elections, when they happen, and vote for the least harmful candidate. That’s common sense. But we should not see elections as the domain where we express our deepest political values, or give them an outsized role in our understanding of what politics is. Instead, we need to be working the rest of the time for the betterment of our world in different ways. Sometimes that involves running candidates in elections, and trying to improve the slate on offer—hence the Sanders campaign, AOC, the dozens of DSA elected officials around the country. But that’s only one part of what we do. We are also building institutions; unions, media organizations, pressure groups and political organizations. We are working slowly on building power, which cannot be done in general elections. That’s news to nobody, yet everyone’s attention is still fixated on national presidential politics to an unhealthy degree, to the neglect especially of state, local, and international politics.

I don’t think Chomsky, Gray, or Texas came out of their conversation happy, but I ultimately think their positions are closer than they realize, and I think leftists with common aspirations should be able to come together around the same basic approaches—that is, once they are made clear, and we all understand each other.