Obama’s Words

Revisiting the 44th president’s speeches helps us understand why his politics were so limited, and what we need instead.

I did not agree with much that Christopher Hitchens said during this century, but in 2008 he made an observation about Barack Obama that has stayed with me for years. Commenting on the fact that millions of people watched Obama’s famous “race speech,” Hitchens said: “Ask any one of them if they can quote two words of it… There’s not a single memorable phrase in it… One of the most boring speeches ever made.” I was taken aback when I first heard Hitchens say it—at the time I was not as cynical about Obama as I would one day become. The race speech, “A More Perfect Union,” was called at the time a “tour de force,” the crowning speech of Obama’s career at that point, and compared with the greatest speeches of Abraham Lincoln. It was considered a turning point in his campaign, and spawned an entire book of commentary.

The speech is still of historical interest; in it, Obama addressed the “controversial remarks” of his firebrand pastor, Rev. Jeremiah Wright (“God damn America for treating our citizens as less than human!”—the networks often just played the first three words). Obama attempted to explain to white Americans why Black Americans like Wright might be angry, while distancing himself from that anger and condemning Wright’s remarks as “racially charged at a time when we need to come together.” It was an exercise in tightrope-walking in which Obama tried to express pride in his Black identity without appearing, it seems, too radical in challenging the status quo. Obama encouraged Black Americans to “[embrace] the burdens of our past without becoming victims” and encouraged white Americans to “acknowledge that what ails the African American community does not just exist in the minds of Black people” so that together we may “move beyond some of our old racial wounds” and end “a politics that breeds division and conflict and cynicism.” Obama succeeded in defusing the controversy, and the speech attracted bipartisan praise, not just from progressive and progressive-ish people like Barbara Ehrenreich, Tom Hayden, and Jon Stewart, but from hardcore right-wingers like Newt Gingrich, Mike Huckabee, and even Charles Murray.

Yet when I heard Hitchens’ comment, I realized he was right that I couldn’t remember a word of the speech, and I doubted anyone else could either. And, looking back, isn’t it a little odd that there could be such unanimous praise for a speech on a topic so controversial as race? If Charles Murray, a white supremacist, liked it, could there have been anything in it that aggressively challenged white supremacy?

In fact, though there is a consensus that Obama was a great speech-maker, I can remember hardly anything he said during his rise to power or his time in office. I remember that kumbaya stuff from the 2004 convention about how there is “no red America or blue America but only the United States of America” (which was as false then as now: there is indeed a red America and a blue America and they often want to tear each other’s faces off.) I remember him saying that the Cambridge police “acted stupidly” in arresting Henry Louis Gates, Jr. on his own doorstep, before inviting the arresting officer to come and have a beer with him and Gates at the White House. I remember Obama saying in 2008 that we would hopefully look back on his nomination as “the moment when the rise of the oceans began to slow and our planet began to heal,” then I remember him in 2018 suggesting the fossil fuel industry should be more grateful for his work: “Suddenly America’s the biggest oil and gas producer—that was me, people!” But I do not remember too much else.

* * * *

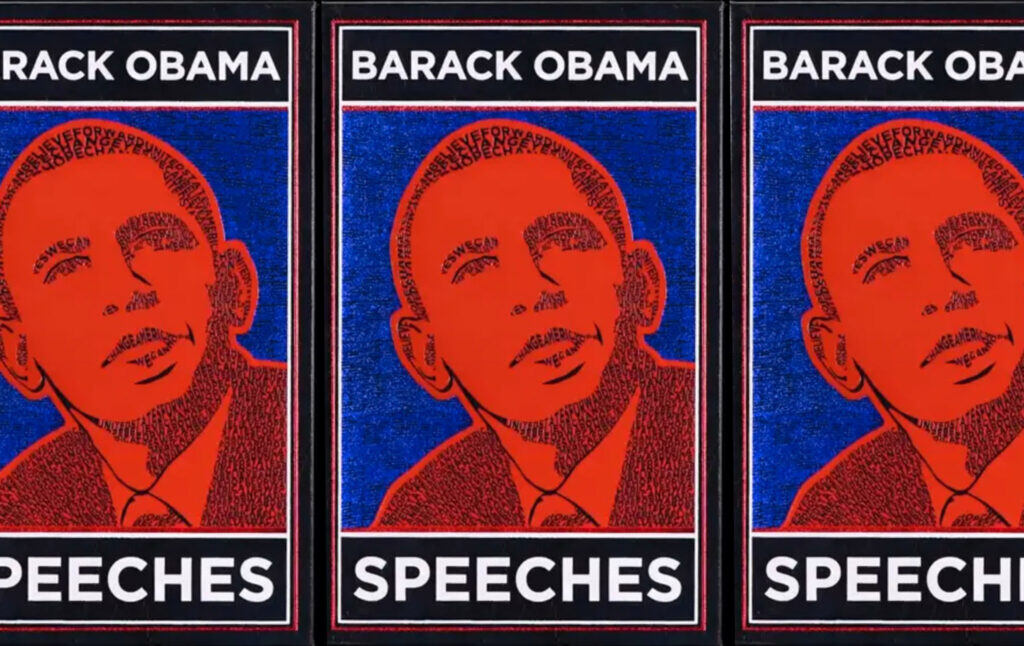

I have on my desk a 670-page leather-bound collection of Barack Obama’s speeches called, simply, Speeches, newly published from Canterbury Classics. It is a luxurious collectible volume. On the cover, a stylized portrait of Obama based on the Shepard Fairey poster is made from words like “Believe,” “Hope,” “Forward,” “Change,” and “United States.” (His right eyebrow spells “Yes We Can.”) It has gilt edges and a sewn-in ribbon bookmark. If someone in your life adores Barack Obama, it would make an excellent gift.

It also affords a useful opportunity to look back over Obama’s words, to try to appreciate them as a unified body of work, and to remember what we forgot and why we forgot it.

The first thing to note about Obama’s speeches is that Hitchens is right that the language wasn’t memorable, but he was wrong that they were boring. In fact, Obama was a deeply compelling speechmaker. He could be funny one moment and heartfelt the next. He incorporated history, personal stories, Biblical references, statistics, and deep appeals to people’s innermost values and aspirations. He was compulsively charismatic and watchable. John Kerry is boring. Barack Obama made people laugh, weep, and want to cross hot coals for him. Rereading the speeches, I could not help but be moved. Obama’s eulogy for the Rev. Clementa Pinckney—shot down with eight other Black worshipers by a white supremacist—and his speech at a Sandy Hook prayer vigil are sincere, unpretentious, and beautiful tributes to the dead, perfectly calibrated to the occasion.

But a president is not just supposed to be a consoler-in-chief. The president is also a maker of policy given an immense amount of power and influence and tasked with solving social problems and influencing the direction of events. The president has to do politics. And here is where rereading Obama’s speeches immediately reminds you what made his eight years in office so exasperating. Obama did not like doing politics. He wanted to end politics. He believed politics was divisive. He aspired to unify the country around shared values and to end partisan division, which he saw as a giant misunderstanding among people whose passionate feelings had made them overlook the fact of their common humanity.

This was present in his “no red America, no blue America” speech, and it was in his speech upon winning election to the senate, which said that “what this campaign has been about” is “set[ting] aside the scorched earth politics, the slash and burn politics of the past,” in favor of “practical common sense solutions.” It was a core part of his pitch when he first announced his presidential exploratory committee in 2007:

It’s not the magnitude of our problems that concerns me the most. It’s the smallness of our politics. America’s faced big problems before. But today, our leaders in Washington seem incapable of working together in a practical, common sense way. Politics has become bitter and partisan, so gummed up by money and influence, that we can’t tackle the big problems that demand solutions.

The language recurred over and over. In 2010, during the fight over healthcare, Obama was insisting that “if we’re going to solve the great challenges of our time… we’re going to have to care less about scoring points and more about solving problems.” We need to “come together around our common interests” and “disagree without being disagreeable.” We must end “the petty grievances and false promises, the recriminations and worn-out dogmas.”

The enemy, then, was not the power of the ruling class, but “dogma” and “scoring points.” But Obama was often very vague: which dogmas specifically are “worn out”? What is an example of a petty grievance? What are people bitter about? When Obama says we must “put aside matters of party for the good of the country” what are those matters? Why are people in parties to begin with? There’s something a bit patronizing underlying all this, because it treats those who are “partisan” as if they are irrational, that while they are petty and fail to see the big picture, Obama stands above it all, gazing down on the world and seeing that the “recriminations” are unwarranted.

One reason this is so bothersome is that, while Obama took great pains to “subtweet” his targets, rarely saying who he was actually talking about, as a leftist I know he was referring in part to the things I believe and care about. In 2006, for example, in an address on “faith and politics,” Obama gave an example of what he meant by divisive politics. He said that during his senate campaign, he had received a message from a doctor strongly opposed to abortion. The doctor noted that on Obama’s campaign website, it said the candidate promised to “fight right-wing ideologues who want to take away a woman’s right to choose.” The doctor objected, saying that he resented being called a right-wing ideologue merely for his strong moral stance against abortion, and that while he did not ask Obama to oppose abortion, he wished Obama would use “fair-minded words.”

“I felt a pang of shame,” Obama said. While the text was “standard Democratic Party boilerplate language,” people like the doctor are looking for a “deeper, fuller conversation about religion.” “The next day I changed the language on my website,” Obama commented, and said a prayer that he “might extend the same presumption of good faith to others that the doctor had extended to me.”

Here we can see why progressives were destined to be disappointed with Obama. Missing from his address is any explanation of why a woman’s right to choose is important. The doctor did not, in fact, do any work himself to be empathetic and understand the other side. The doctor was aggrieved on his own behalf, and Obama was ashamed that he had hurt the doctor’s feelings. But why is it, after all, that those on the left fight so hard to preserve the right to abortion? It’s because “taking away the right to choose” is not just an abstraction; criminalizing abortion means throwing poor women in jail. The doctor might resent being called an ideologue, and perhaps that word in particular isn’t right. (Personally I think it’s more accurate to say “right-wingers who will happily inflict suffering on the poorest to enforce their perverse idea of what it means to ‘care about life.’”) But why are we required to show we care about the doctor while the doctor isn’t required to show that he cares about the people who will be hurt by his favored policies?

This is an example of how “not taking sides” often does implicitly take sides. Obama’s disavowal of partisanship wasn’t just naive, it was false, because it involved treating one perspective as worthier of consideration. We could see this in his comments on Israel-Palestine. Here, Obama took great pains to insist that he sought only to help bring peace between two people who both wanted the same things, i.e. for their children to live in peace and prosperity. He would make sure to always explain why both Judaism and Islam were great traditions, and why people of faith had more in common than that which divided them, and would tut at Israel over settlement expansion and tut at Palestinians over terrorism. But there was a one-sidedness underneath the rhetoric. Palestinians were told that they “must abandon violence” because “resistance through violence and killing is wrong and it does not succeed.” Israelis, however, were not told that killing is wrong and they must abandon violence, even though they are responsible for the bulk of the violence including the mass murder of civilians. Furthermore, Obama promises that he will “maintain Israel’s qualitative military edge,” by making “our advanced technologies available to our Israeli allies, and that “despite tough fiscal times, we’ve increased foreign military financing to record levels” including “additional support…for the Iron Dome anti-rocket system.”) Do Palestinians, too, get record levels of new military funding? (Note that when Obama says “tough fiscal times,” he means that he was pushing cuts to Social Security and Medicare at home, meaning that military aid to Israel was more important than domestic social spending.)

Kindness to one party can be cruelty to another. Consider this passage on national security:

Some of the unity we felt after 9/11 has dissipated. We can argue all we want about who’s to blame for this, but I’m not interested in the past. I know that all of us love this country… [There is a] false choice between protecting our people and upholding our values. Let’s leave behind the fear and division, and do what it takes to defend our nation and forge a more hopeful future.

Now, the Bush administration committed one of the most hideous crimes in recent American history. The “post-9/11 unity” Obama is speaking of positively here was in part a jingoistic and Islamophobic national hysteria that produced two catastrophic wars. To say that we should not discuss “who is to blame” is to implicitly exonerate wrongdoing, or at least to sweep it under the rug. Obama said he didn’t want to prosecute Bush-era torturers because he wanted to “look forward, not backward.” To see the absurdity of this, we can imagine how it would sound for any other crime. In cases of murder or sexual assault, would it be neutral and fair-minded to say that we were “not interested in the past”? Or would it be taking a side? (In fact, instead of prosecuting torturers, Obama decided to prosecute the CIA official who leaked evidence of the torture program.)

It is easy to sustain the rhetoric about common values and aspirations only when you speak at the most abstract level possible and say things that nobody could possibly disagree with. In fact, one of the reasons Obama’s speeches are inspiring and people like them is that they are carefully crafted to say almost nothing objectionable: “We want to pass on a country that’s safe… We believe in a compassionate America.” There is an interesting exercise one can do with political speeches where you invert the statement and see if anyone could reasonably hold the contrary position. Are there those who would claim to be supporters of an unsafe, non-compassionate America? I believe in a better future for all. Well, does anyone believe otherwise? I believe in a free and prosperous country, as opposed to those who believe that freedom is bad and poverty is good. The whole question is what words like “better,” “compassion,” “freedom,” and “prosperity” actually mean, because definitions vary. Yes, it is possible to say that “we all” believe our children should be free. But for some people, freedom means that a company should be able to pay you $3.00 an hour if they can get you to agree to it. Some believe “compassion” means not making people “dependent” by helping them when they are struggling. The positive nature of the abstraction is agreed upon, but its content is highly contested.

Obama’s speeches frequently attack imaginary enemies. “We reject the belief that America must choose between caring for the generation that built this country and investing in the generation that will build its future,” he says. Or, he goes after those who are “skeptical of the possibilities that our children can enjoy a better future than we had.” There are “some who question the scale of our ambitions, who suggest that our system cannot tolerate too many big plans.” Are there? Who? When did they say these things? Obama does draw some stark lines between himself and Those Who Differ, but he always restricts himself to the narrowest possible group of crazies or bigots. He is extremely cautious and wants to include as wide a swath of people as possible in the category of Those Who Must Come Together Around Practical Solutions And The Common Good. (It doesn’t include David Duke, but it does include homophobic megachurch pastor Rick Warren, whom Obama chose to give the invocation at his inauguration.)

Over and over, Obama laments that we differ, without grappling with why we differ. Israel and Palestine are in conflict. Is this because of a misunderstanding? Or is it because many Israelis believe they are divinely entitled to the land that Palestinians occupy, and Palestinians are resisting displacement by a militarily stronger power? If two parties are angry with one another, until you get at the root of their disagreement, you can’t resolve it in a just manner, because one might be right and the other might be wrong, or do not share equal measures of blame. If you just say “look, clearly we disagree, why don’t we tone down the bitterness and reach a compromise?” you might be demanding something very unfair, if one party was wronged. So, for example, Obama laments that we “continue to spin our wheels with the old education debates” that pit “teachers unions against reformers.” But the argument that the teachers unions make is that “reformers” are often privatizers who do not actually value ensuring that teachers’ labor rights are protected and whose plans will ultimately dismantle the public school system. Are they right? The “old debates” will persist until they are resolved. They can’t be transcended or set aside.

Obama was frustrating because he stubbornly refused to understand that his project of being a unifier was doomed to fail not because people were “too locked into partisanship and bitterness” but because it failed to actually grasp the causes of that partisanship and bitterness. In one speech later in his presidency, he says that while he knows some think it is “ironic” that a president committed to bridging divides has overseen their expansion, he still has faith in the American people, he still believes we can be our better selves, etc., etc. Essentially, he saw himself as trying to heal us as we tore ourselves apart. What was annoying about his stubborn maintenance of this stance is that Obama was not self-critical. He did not wonder if perhaps simply calling for an end to bitterness was actually an insult destined to make people more even more bitter.

In order to try to appeal to everyone, Obama laced his speeches with endless “buts,” which is one reason they’re difficult to remember. He qualified everything to the point of saying nothing. Every time it feels as if he’s going to make a strong statement, he quickly points out that those who disagree also have a point.

- The economic crisis was “a consequence of greed and irresponsibility on the part of some, but also our collective failure to make hard choices and prepare the nation for a new age.”

- “I believe in vigorous enforcement of our nondiscrimination laws. But I also believe that a transformation of conscience and a genuine commitment to diversity on the part of the nation’s CEOS could bring about quicker results than a battalion of lawyers.”

- “Living testimony to the moral force of non-violence. But as a head of state sworn to protect and defend rny nation, I cannot be guided by [King and Gandhi] alone.”

We are a strong country, but a just one. We are proud, but we are humble. We are peace-loving, but we are tough-minded. We condemn greed, but we reward success. We are cautious, but we are bold. This explains why Obama could appeal to anti-racists and Charles Murray alike. He said things nobody could disagree with, and when he said things people could disagree with, he instantly followed them up with qualifications. Lest anyone think him a pacifist in a speech praising Gandhi, he insisted he would not be guided by Gandhi alone. Lest anyone think he planned to bring the boot of the law down on discriminating companies, he made clear he believed more in the moral transformation of CEOs. Lest anyone think he was just blaming Wall Street, he also blamed “our collective failures” for the 2007-08 catastrophe.

Obama quickly found out why this mindset, which could produce inspiring speeches on the campaign trail, could only lead to political failure. If, in a two-party negotiation, one party wants to win at all costs and the other’s goal is merely to reach a harmonious agreement, the resulting compromise will favor the ruthless party. A tug of war between right and left requires a left, but under Obama, Republicans weren’t really being opposed by a Democrat, they were being opposed by a moderator, who was uncomfortable with anything that seemed like ideology/rancor/divisiveness.

It’s sad to read how many of these speeches are spent pleading with the American public to see how reasonable of a deal Obama is offering the Republicans. He promises he will “seek the best ideas from either party” despite knowing full well that the Republicans have only one idea, which is to drown the government in the bathtub, end democracy, and let the country be run by corporations. He comes across as positively obsessed with reducing the deficit, and constantly talks about the need to massively reduce government spending, begging the right to give him a few tax hikes in exchange. He insists he has promised the “lowest level of annual domestic spending since Dwight Eiesenhower was president,” and knows we need to make “tough choices” including cutting “$2 in spending for every dollar in new revenues.” He swears that he disagrees with “some in my own party” who oppose his “modest adjustments to programs like Medicare.” He says he has pledged a spending freeze that will “require painful cuts.” Reducing the deficit, he says, should be a bipartisan issue because “math is not partisan” so “the reality of our fiscal challenge is not subject to interpretation.” (In fact, this is false.) And he simply can’t understand why Republicans won’t meet him halfway when he has been so reasonable and promised to slash government programs and give so much away.

Republicans, of course, understood that Obama had gotten himself into a huge pickle by promising to be a unifier. It meant that he had promised not to fight very hard, because if he started to fight, he would look like a hypocrite, since political fights are the things he said he didn’t believe in. And since Obama’s entire pitch was that he was against hypocrisy and in favor of good-faith dialogue, the more that he would need to “act like a partisan” in order to win, the more he would erode his own brand and betray his highest aspirations. Going to Washington and promising you’re not going to be partisan is like walking onto the schoolyard and announcing loudly that you believe in Gandhian nonresistance and if anyone hits you, you will not hit back. It is positively inviting a pummeling.

So Republicans knew they could steamroll Obama because he had told them they could. But leftists also knew that he had disdain for them, because he was constantly treating our “partisanship” as just as much of a problem as right-wing “partisanship.” Nobody on our side likes to be told that vigorous insistence on the right to choose is just as much of an obstacle to social flourishing as the vigorous insistence that abortion should be prosecuted as murder.

But Obama did not just treat “both sides” as part of the problem. He also embraced many deeply conservative positions, whether out of sincere personal conviction or his unshakable belief in the principle of “balance.” There is, of course, the deficit hysteria, and it’s alarming to see Obama saying he is “pleased that Congress supported my request to restore the pay as-you-go rule.” But there’s so much more. On immigration he talked of the need “to secure borders and enforce our laws” (which meant, for him, mass deportation) and boasts that he is putting more “boots on the Southern border than at any time in our history and reducing crossings to their lowest levels in 40 years.” He says the government “should do more to promote marriage and encourage fatherhood,” and used a discomforting amount of “personal responsibility” rhetoric in hectoring people to make better choices and not expect the welfare state to help them. He is proud that “we’ve imposed the toughest sanctions ever on the Iranian regime,” even though these sanctions restrict ordinary Iranians’ access to food and medicine. In response to the calls of many progressives for single-payer healthcare, Obama says:

There are some who’ve suggested scrapping our system of private insurance and replacing it with a government-run health care system. And though many other countries have such a system, in America it would be neither practical nor realistic.

He doesn’t say why it would be “neither practical nor realistic” but does mention not wanting to empower “government bureaucrats” and elsewhere suggested that the parasitic private insurance insurance industry should be preserved because it creates jobs.

The conservatism is also evident in what Obama leaves out of his speeches. Though there are occasional references to unions as a positive thing, he rarely speaks of labor rights. During his first presidential campaign he promised to support the Employee Free Choice Act, which would have made it much easier to unionize, but he quickly went silent on it and then abandoned it altogether.

Obama does sometimes talk about climate change, which he admits rhetorically is real and urgent (we must “roll back the specter of a warming planet,” an odd way of putting it), but it’s clearly a secondary issue, and he usually just refers to the need for a “clean energy future.” Worse, Obama’s pathological need to be balanced means he is constantly insisting on the need for an “all of the above” energy future that embraces fossil fuels. Instead of condemning the fossil fuel industry for lying about climate science for years and running a business that depends on destruction for its profits, he boasts that he “opened millions of new acres for oil and gas exploration,” and promises that his administration will “keep cutting red tape and speeding up new oil and gas permits.” He encourages Congress to “get together [and] pursue a bipartisan, market-based solution to climate change,” as if there can possibly be a “bipartisan” solution found when the opposing party’s beliefs on climate change range from “it’s a hoax” to “people can just move.” Nowhere is the absurdity of a “getting everyone together to compromise” approach more absurd than on the issue of climate change, where the continued profits of fossil fuel companies depend on continuing to make the problem worse. This may be one reason why Obama was reluctant to wade into the issue.

Throughout Obama’s speeches, he appears a sincere and good-hearted person who wants the best for Americans and is honestly trying to grapple with the challenges of being a “president for everybody.” But I am reluctant to give him much of a break, in part because he was not always willing to be honest about what he was doing. Obama appointed a climate change-denying BP scientist to his Department of Energy, and despite boasting in one of his speeches that he “helped forge an accord in Copenhagen that—for the first time—commits all major economies to reduce their emissions,” his administration actually severely undermined the Copenhagen talks. If Obama had been willing to say openly, “I believe in deportation, I believe that sometimes it is okay to kill children with drones, and I believe that whistleblowers should be prosecuted,” I might actually respect him more. But because he knew these positions would be unpalatable, he often made false promises, like saying he would operate “the most transparent administration ever.” It is hard to fully accept as credible someone who was unwilling to be frank about what they were doing.

Sometimes, then, Obama’s speeches are a sincere statement of a naive position, and sometimes they are nefarious in burying the reality of what his government actually accomplished. They are often emotionally touching, particularly when they tell people’s stories, but they never have much fight in them. In one speech, for instance, he tells a story of a 104-year-old woman who waits hours to vote because she still “believes at 104 that her life counts and her vote counts.” I am inspired by that but I am also angry, and he should have been angry too, because making a 104-year-old woman stand in line for hours is criminal. He should have named and shamed those responsible for putting that woman through that ordeal. (I am reminded here of the “inspiring” stories in local news about how a group of people has gotten together to pay for the medical treatment of a coworker whose treatment should have been free to begin with.)

There are also the frustrating little neoliberal touches, the celebration of “competition” and “choice” without closely examining what those things mean in practice. Obama talks of the importance of science and math teachers, but not the importance of art and music teachers, and reinforces the idea that the job of school is to prepare students to compete against other countries, against which we are falling behind, when the job of school is to prepare you to be a thoughtful person who has a good life. Jobs are spoken of as a good thing in and of themselves, as if the purpose of life is to work for someone. And Obama proudly speaks of the Affordable Care Act as if it were designed to solve the healthcare affordability problem once and for all, when its basic structure is partly responsible for its failure to solve the problem. (The fact that a person has to affirmatively buy insurance rather than being insured automatically means that a lot of people have ended up uninsured who should not be.) He talks a great deal about markets and incentives and not nearly enough about what people have a right to expect.

What Kind Of Politics Do We Need?

Why go back through and scrutinize Obama’s speeches now? Why criticize him long after he’s gone, especially when Donald Trump is far worse and getting rid of Trump is such an urgent priority? Because we need to understand what was wrong with Obama’s politics in order to understand how to do better next time. Joe Biden, if he wins, will probably exhibit many of the same tendencies that made Obama’s tenure so disappointing—in fact, Biden will likely be much worse. We will need to offer something better, and we need to understand what that looks like. During Obama’s presidency, we on the left constantly argued with Obama’s defenders, who insisted that he was a serious progressive but unable, due to political circumstances beyond his control, to achieve as much as he had hoped. Because Republicans are so intransigent and ruthless, the excuse was plausible on its face.

But it’s very clear just from reading his words that Obama’s core ideology was not progressivism. He would probably have been reluctant to identify himself as being “on the left,” since even to say he was part of “blue America” would have admitted that such a thing existed. Obama was ashamed to even say that he would fight to protect a woman’s right to choose from attacks by right-wing ideologues. Of course he wasn’t fighting hard but losing; he saw fighting as the problem!

Many of those in my generation of leftists grew deeply disillusioned during Obama’s time in office. Occupy Wall Street developed under Obama, in part as an expression of that frustration, and Obama is a major reason why so many young people were attracted to Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. Obama wanted to be a healer, and we didn’t want a healer, we wanted a brawler, someone who would kick Republicans in the teeth. Sanders had previously tussled with Obama over Obama’s plans to cut USPS deliveries and Social Security, and in him we saw somebody who would fight hard for social democracy and not compromise his values.

We’ve seen the same thing in Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who takes a far more confrontational approach with the right. Contrast Obama’s embarrassment at having been too aggressive on abortion rights with a recent AOC tweet on the hypocrisy of pro-lifers:

“Just to be clear: there is nothing “pro-life” about denying people comprehensive sexual education, making birth control harder to access, forcing others to give birth against their will, and stripping them of healthcare and food assistance afterwards.”

That’s the kind of person I want in office: someone who doesn’t take shit. Obama often talked generally about Wall Street abuses of power, about the “lobbyists and special interests, who too often hijack the agenda by leveraging campaign money and connections.” But he was reluctant to name names, to confront anyone directly. (AOC grills bank execs until they squirm.) He was a nice man, but I don’t want a nice man, I want a grumpy SOB like Bernie who will show the correct amount of indignation toward those who hoard wealth while others are being evicted and losing their healthcare by the millions. And I don’t want to keep hearing excuses about why things can’t be done, but a determination to build the kind of political movement that will get them done. We young socialists love AOC and Bernie because they set ambitious goals rather than incremental ones, and they do not prematurely capitulate. There is a misconception that this approach is impractical and idealistic. In fact, it is far more likely to yield political success than Obama’s “pragmatic” approach, which does not grasp how power is built. Ironically, in pursuing political goals, it is far more pragmatic to be a radical than a conciliator.

* * * *

Obama’s speeches are padded with uplifting fluff. He is constantly talking about our “journey” and our “future,” how far we’ve traveled and the distance we’ve yet to go, and drizzles everything with what Sarah Palin derisively called “that hopey changey stuff.” His first inaugural address ends like this:

In the face of our common dangers, in this winter of our hardship, let us remember these timeless words. With hope and virtue, let us brave once more the icy currents, and endure what storms may come. Let it be said by our children’s children that when we were tested we refused to let this journey end, that we did not turn back nor did we falter; and with eyes fixed on the horizon and God’s grace upon us, we carried forth that great gift of freedom and delivered it safely to future generations.

This sort of thing can fill the heart. It can feel good. But it can also be said by anyone of any political persuasion. It needs content.

Unfortunately, when Obama did give content to his words, it often helped the right. Like Bill Clinton, he talked of low taxes, cutting spending, charterizing schools, free trade, tough sanctions, secure borders, etc. When Democrats do this, they essentially concede that the conservative stance is correct, and end up getting into a (crazy) argument with the right over things like who will lower your taxes more and who is the true heir of Ronald Reagan. (Obama, of course, liked to say that Republicans were betraying the spirit of Reagan while he was honoring it.)

I’ve written before about the political dead end of using right-wing assumptions to make supposedly progressive points. We saw another example of this is in the debate between Kamala Harris and Mike Pence, who ended up competing over which of them loves fracking more. Instead of sticking up for environmentalists, Harris essentially accepted that the conservative stance was right. The way to kick Mike Pence’s ass on the Green New Deal is not to insist you don’t support it, but to point out that he is a nitwit who doesn’t understand the first thing about how the program works. The way to go after conservatives on taxes is to point out that taxes make us wealthier, not poorer, by paying for stuff that makes us better off, rather than taking the Harris-Biden approach of insisting that anyone making less than $400,000 doesn’t have to worry about their taxes going up.

We need politicians who are willing to come out swinging for left values, who are willing to defend taxes, immigration, government spending, welfare programs, etc. as good things. Obama tried to appease the right by insisting that he was cutting more spending and imposing more sanctions than any previous president. Screw that! Tell them where they can stick their austerity. We demand a government that actually ensures people have a basic standard of living for all, and if we have to tax rich people through the nose to get that done, we’re going to do it.

I do think it’s important to put Obama in context and try to be as sympathetic to him as possible. It is quite clear that one reason he was reluctant to be too aggressive is that he was trying to succeed as a Black president in a racist country. Obama was attempting something that had never been done before, and he clearly felt he needed to be as wholesome and all-American as possible. If he had said “the Founding Fathers were immoral and the Constitution is an illegitimate document” he could never have risen to the presidency.

But it’s also clear by this point that there is no “inner radical” in Obama, and that he believes wholeheartedly in the possibility that the American meritocracy could be fair. I believe Obama’s ideology is a sincere one, in that he genuinely still does not see politics as a clash of irreconcilable interests. He hammered the same themes in his final speech as president that he did early in his career: that Americans are one people whose disagreements should not tear them apart. By the end, I was extremely tired of it. I can’t accept that it is moral to decline to criticize Donald Trump with the same level of intensity that Trump is willing to criticize Obama. I don’t think being “above the fray” is either possible or acceptable. As we’ve seen, Obama was in practice simply conservative on many issues, unwilling to take on the private insurance industry or the fossil fuel industry or increase the rights of unions. He fully subscribed to right-wing “deficit panic,” and saw getting along with people as more important than getting justice. We can understand why Obama might have held this perspective, and even be inspired by him, while understanding that his approach to politics simply will not achieve the kind of “change” he promised. Obama’s words are well-crafted and well-delivered, but they are often just pleasant words in a time that calls for real actions.

Bonus: Your Very Own Obama Speech Mad Lib

After reading 670 pages of Obama’s speeches, and seeing the themes that recur over and over, you will be able to put together an Obama Speech of your own. Here is mine:

I come to you tonight to affirm the continued existence of [universally-agreed upon Good Thing 1]. There are those who say that [Good Thing 1] is dead. They say [Good Thing 1] is getting worse and that that is good. Well, I dare to believe that it isn’t good. That we can still [pleasant abstraction 1]. That we can [pleasant abstraction 2]. I am a product of such a [pleasant abstraction 1], and I have met people around this country who have [pleasantly abstracted] that [pleasant abstraction 1]. People like [cute but generic girl’s name], a [number between 6 and 11, the cute ages]-year old in [middle American city] who has a [bad thing going on]. When I met [girl’s name], she told me that she hoped she could vote for me. I told her that would be voter fraud! But we need more like [girl’s name]. Yes, we do. And we see them, in places from [small middle American city] to [small middle American city] to [honestly just make up a plausible name for a small middle American city]. We know that these people share a common [pleasant abstraction 3], forged from a shared [pleasant abstraction 4] It is a [pleasant abstraction 3] that burned in [slave-owning American president] as he [accomplished thing he’s famous for that wasn’t owning slaves], and in the soldiers who [participated in specific WWII event, no other wars allowed]. It is the [pleasant abstraction 3] that gave [relatable description of Obama as a child] the [pleasant abstraction 5] to [pleasant abstraction 6] when people told him it couldn’t be [pleasantly abstracted]. And you proved him right. Now, I don’t say there aren’t [less pleasant but not exactly negative abstraction]s. Our [less pleasant but not exactly negative abstraction]s are many, and they are great. Nor do I say that it will be easy to meet them. We’re gonna have to [euphemism for killing poor people]. We’re gonna have to [word that sounds mature and respectable in the abstract but in practice also means killing poor people]. We’re gonna have to cut [vague, weaselly adjective for important federal programs] and give [oppressive ally] a hundred billion dollars worth of new [horrifying weapons that will be deployed against civilians]. We’re gonna have to not investigate some [quaint synonym for “people”] who [verb for an act of barbaric personal cruelty] some [quaint synonym for “people”]. No one ever said this would be easy, but we’ve shown that we’re willing to [pleasant abstraction 7] for the sake of that [pleasant abstraction 1], and that we will keep moving [direction] when they tell us we should go [different direction]. Together, though, we can create a [Good Thing 2] for all of us. We can dare to believe that the [negative abstraction] is [inverse of the negative abstraction], that there can be [social goal required for the preservation of our planet] AND a thriving [industry that is actively destroying our planet], that we can cut the size of [political concept] even as we expand the size of our [plural body part]. We do not scale back our [characteristic that is often treated as desirable under capitalism but is in practice highly unpleasant]. We believe in [political concept], but we also [pleasant abstraction 8]. There are some who say it is not possible to give [Republican talking-point] a [Democratic talking-point word salad]. We dare to say that these people are wrong. But at the end of the day, we are all [nationalist phrase]. There are no [members of the party that is actively trying to preserve their political power even if they have to destroy democracy to do it]. There are no [members of the party that wrings their hands over the first party but also is actively trying to preserve their own political power even if they have to destroy the left to do it]. There is only [pleasant abstraction 9], and the [pleasant abstraction 9] we can agree on. [STEM cliche] has no party affiliation, [noble abstraction that can never be reached through compromise and negotiation] has no congressional district. All of us together are ourselves, and together we will [word salad about travel]toward a [vague adjective] tomorrow. Our history tells us we are many people who are also one. [Corny Latin motto]. The [noun related to travel] is difficult. But it is worth [verb related to travel], if you have [pleasant abstraction 1]. Thank you, and [uncomfortably religious statement for a country that technically enjoys the separation of church and state and does not want to investigate that conflict at all because it would be “divisive.”].

My latest book, American Monstrosity: Donald Trump—How We Got Him and How To Stop Him, is now available from OR Books.