Democratize the Federal Bureaucracy

The federal bureaucracy wields vast power—why are their leadership positions appointed instead of elected?

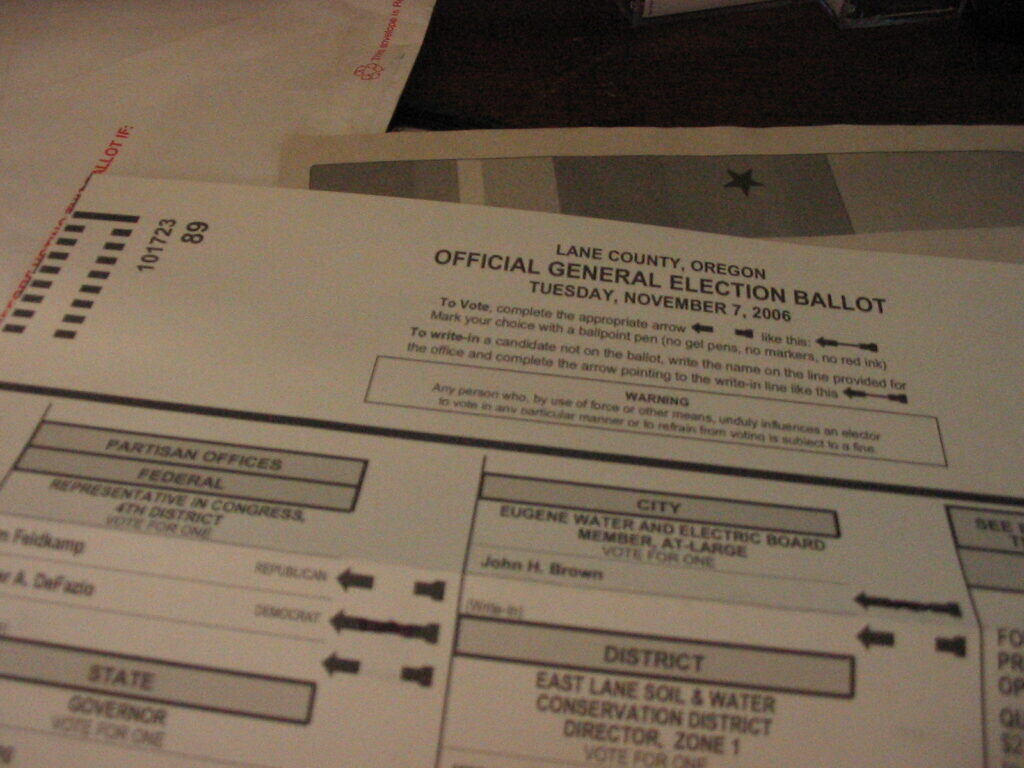

It’s November 5, 2024. You have grudgingly accepted that you have to vote for the Harris/Buttigieg presidential ticket to stop Tucker Carlson’s fascist plan to build a moat with sharks on the Southern Border. You’ve even sort of convinced yourself that you are voting for the Democrats, and not just against the GOP, because they’ve promised (really this time!) to sign the public option into law. You’re struggling with student loans, low pay, and credit card debt, and you’re not exactly thrilled at the prospect of a Harris presidency. On the other hand, you don’t feel entirely hopeless, because look at some of the other great people on the ballot! There’s Sara Nelson, president of the Association of Flight Attendants, running for Secretary of Labor! And Randi Weingarten, president of American Federation of Teachers, running for Secretary of Education! And Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen, running for the Director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau!

The federal bureaucracy is in trouble. Those of us who have been keeping track of what federal agencies have been up to under President Trump have been pretty struck by this administration’s naked pursuit of private interests at the expense of the public good. Federal agencies whose role is nominally to serve the public have been brazenly co-opted or internally sabotaged by their Trump-appointed leaders, a pattern that has repeated itself across almost every part of the federal bureaucracy. The Department of Education has been transformed into a state-backed soapbox for a billionaire whose main interest is touting private school vouchers. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has been impeded “from within” by its former Acting Director; it now prefers allowing predatory payday lenders to perpetuate poverty rather than to maintain minimal consumer lending regulations. The Secretary of Housing and Urban Development has nearly finished instituting a rule that will eliminate the regulations which once made it harder to racially segregate housing. The Post Office is being led into the ground by a handpicked Trump donor who has tens of millions invested in businesses that compete or work with the Post Office. The list goes on.

The action and inaction of these secretaries and agency leaders serves two purposes; first, by wrecking whatever actually useful work was being done by these agencies, they confirm the Republican narrative that the government is not effective; second, by dismantling regulations and oversight in a variety of sectors, they often end up saving their plutocrat backers some money.

When Democrats complain about the Trump administration’s changes to federal agencies, they often throw out the accusation that Trump is inappropriately “politicizing” the executive bureaucracy. This, however, is somewhat disingenuous. It’s not as if Democratic presidents don’t use political appointees at federal departments and agencies to advance their policy goals. To be fair, I prefer Democratic political appointees, because Democrats occasionally advance the public interest over plutocratic interests. It is the lesser evil, after all. But if Donald Trump’s presidency should teach us anything about politics and policy, it is that everything comes down to who wields power, and how much power they’re allowed to have. Neither the popular opinion of the majority, nor the specialized opinions of scientific and subject-matter experts, have any hard power to influence what these unelected decision-makers will do.

Let’s talk about the kind of power the federal executive bureaucracy has. We all learned in civics class that there’s a division of powers between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. However, in the modern U.S. state, the president has at their disposal a sprawling federal bureaucracy with significant quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial power. Originally, the framers of the U.S. Constitution probably expected the bureaucracy to be small and its procedures largely managed through Congress. But as the country grew, industrialized, and new ideas coalesced into the Progressive and New Deal periods, the bureaucracy expanded. Today, the federal bureaucracy is staffed by a professional civil service with over 3,000,000 employees, organized within fifteen cabinet departments and dozens of independent agencies and bureaus.

The academic consensus is that the modern state, with its social services and safety nets, actually requires this extensive and professionalized bureaucracy to function. The capture of legislative and judicial powers within the executive branch are a necessary evil, the argument goes, because the legislature doesn’t have the capacity and expertise to issue the sheer volume of legislation that would be required to allow the government to work. Therefore, the power to make rules and regulations that dictate how these agencies will operate—within the technical but vague bounds imposed by existing legislation and judicial decisions—has to be delegated to the agencies themselves.

The history of the U.S. federal bureaucracy would seem to confirm this view. Professionalization and anti-corruption reforms, largely instigated by progressives, coincided with the expansion of the federal bureaucracy after the New Deal. The Administrative Procedure Act (APA), which formalized the quasi-legislative powers of the bureaucracy, was actually a step forward for accountability, because it mandates a public comment period for new rules promulgated by federal agencies, and defines their quasi-judicial and legislative powers. Today, ensuring the accountability of the U.S. bureaucracy to the public it supposedly serves continues to be an ongoing battle. But despite what some on the left may say about technocrats, I submit that it is not the career civil servants that should bear the brunt of our ire. Rather, we should look to the way the leadership of these federal agencies is selected.

Heads of federal departments and agencies are known as “political appointees,” and for good reason: incoming presidential administrations, both Democratic and Republican, choose secretaries and agency heads who will serve their agenda and interests. Many Democrats view the bureaucracy as something that should be managed scientifically through data-driven policies. Though this management style has certain policy goals, it sees itself principally as executors of the genuine purpose of the various agencies and departments and not as policymakers making political and moral decisions. This “apolitical politicization” is sometimes preferable to Republican politicization that seeks to undo public services and harm minority rights. However, it can be damaging in agencies like the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) where the agency’s purpose itself is actively harmful. And in those agencies where Democratic leadership can lead to generally helpful results, such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), our means of selection of political appointees—i.e. the nascent executive branch more or less gets to pick whoever they want with the Senate’s rubber-stamp—allow for Republicans to dismantle what Democrats build in subsequent administrations.

Democratic Socialist Bureaucracy: A Radical Proposal

Our way of selecting political appointees must change if we want bureaucracy to function stably and in the public interest. When it comes to exercising accountability over an administration’s political appointees, our current methods are fundamentally weak. The president who makes the nominations is chosen in a deeply flawed electoral system where a multitude of different issues unrelated to the bureaucracy (e.g. economic performance and judicial nominees) are in play, and where none of the viable candidates may actually share the majority of the public’s views on the specific topics that fall under various agencies’ areas of responsibility. Ranked choice voting or majority runoff elections would not solve the problem either: the president is one officeholder, and it is practically impossible for that one officeholder to represent the majority opinion on every issue. In other words, electoral reforms to our existing presidential elections, however desirable for other reasons, will not solve this specific problem.

So, instead of struggling against the reality that the federal bureaucracy is politicized, let’s embrace it. We choose political appointees from the top-down. What if instead we chose political appointees from the bottom-up?

Domestic-facing cabinet departments and agencies should be democratized, and run by people elected to the position. The electorate would vote for what are now political appointees: the Secretaries, Deputy Secretaries, Assistant Secretaries, Under Secretaries, Administrators, Directors, and Chairpersons of departments and agencies. In larger departments, these elections could be done via proportional representation, with the requirement that the top vote-getters have to form a leadership team with a supermajority of electoral support. In smaller departments and agencies, with 3 or fewer appointee offices, the leadership could be selected by ranked choice voting.

There are two possible models for these bureaucratic leadership elections. First, under “national electoral bureaucracy,” every American can vote for each bureaucratic leadership team. However, if we imagine such a model being implemented without any accompanying changes to the current campaign finance and party system, this scheme could lead to some very concerning political consequences. National elections are an arms race because you have to reach a lot of voters, which takes a lot of cash; the more money you have, the more voters you can reach. Hence, without significant campaign finance reform including public financing, increasing the number of elections that are carried out on a national scale will mean more private and corporate PAC money being poured into campaigns. This will incentivize candidates to take positions friendly to corporations and the wealthy. Even if we implemented more proportional elections for the bureaucratic leadership candidates specifically, it is still likely that congressional and presidential elections would be run through the two-party system, and therefore candidates running for bureaucratic leadership would have very strong incentives to link up with one of the two main parties and to seek support from their corporate backers. Thus, it’s likely that the viable candidates for a given bureaucratic role will significantly mirror the positions of the main political parties. This electoral model is still better than the totally unaccountable appointment system we have currently—I think diluting the stakes of the presidential and congressional elections by allowing a national electorate to appoint these powerful agency positions would be better than nothing—but without other electoral and campaign finance reforms, it’s unclear whether it would straightforwardly lead to more policies that are in the public interest, given the corporate and elite cash investments that national elections attract.

The alternative to national electoral bureaucracy is stakeholder democracy. In the private sector, stakeholder democracy is a business governance model whereby stakeholders, including employees, consumers, and others with a vested interest in the company’s future, participate in the company’s decisions. We can imagine a version of this model in the public sector as well, and it may, despite its private-sector origins, avoid some of the negative political consequences of national electoral bureaucracy.

Take the Department of Education. In a stakeholder democracy model, the electorate would include public school teachers, parents, public university professors, student loan holders, school and university administrators, and the civil servants themselves. These individuals would vote for the Secretary, Deputy Secretary, and Under Secretary in single-seat elections via ranked choice voting.

Eligible voters for the director of Consumer Financial Protection Bureau would be, let’s say, consumer debt holders and civil servants. The Secretary of Labor would be chosen by unionized and nonunionized workers and civil servants. The Postal Service could even, potentially, become a full-scale worker democracy, since the Board of Governors model has been proven corruptible. Individuals living in public housing could vote for the Secretary of HUD.

In a bureaucracy run by stakeholder democracy, the electorate is limited to those who are affected by the department or agencies’ rules, regulations, and decisions. These individuals have a strong interest in the department’s activities, so they will be more engaged in the electoral process, more knowledgeable about policy differences, and better able to mobilize a necessary amount of the electorate for less money. Combined with a more proportionate electoral system, a stakeholder democracy model would encourage policy debate based on appeals to the interests of those impacted by the department. At a minimum, this system will decrease the sway that money and the two main parties have over policy, at least when compared to national electoral bureaucracy.

There are flaws to such a system—the administration of who gets to count as a stakeholder, what sort of documentation they would have to provide, and vigilance against stakeholder purges by elites—but a potential advantage of the principle of stakeholder democracy (albeit one that is not without its own practical difficulties), is the flexibility of its application. In some cases, such as the EPA, all Americans should be included in the electorate, as we all have a stake and are impacted by environmental policy. But arguably, most of the world is affected by U.S. environmental policy, so some voice of the international community should justifiably be included in rule-making. Similarly, if we insist on having borders, the voices of documented and undocumented immigrants should have some influence on rule-making decisions at DHS. Deciding how voices of non-citizens and ineligible voters could be taken into account, especially when they are a population at-risk, is an aspect of stakeholder democracy that would admittedly be tricky to hammer out in practice (as well as the business of verifying who has the eligibility to vote for which office). However, the principle of stakeholder democracy, applied successfully in one department or agency, can demonstrate that those impacted deserve to have their voices heard in decision-making processes, and may help expand the public’s understanding of democratic participation in a way that makes them more receptive to enfranchising previously-excluded people.

Under either version, Congress would still hold the power of the purse and ultimate law-giving authority, and the general public would still be able to comment when new rules are proposed. But rule-making and guidance would be issued by individuals directly elected by the constituents who are most impacted by the agency’s decisions.

Democratizing these agencies would reduce presidential power and ensure the quasi-legislative powers of the bureaucracy are exercised in the interests of those they are meant to serve. The federal bureaucracy currently provides the means for a single individual, the president, to wield massive and weakly-accountable power over the daily functioning of the entire country. It’s worth noting that the Trump administration uses the federal bureaucracy the way it does precisely because the administration’s desired policies are actually unpopular. At least 64 percent of parents report that they are completely or somewhat satisfied with their public school. A supermajority (65 percent) of Americans prefer diverse neighborhoods to homogeneity. Americans loathe payday lenders and a supermajority (70 percent) want more regulation on payday loans. And Americans love the USPS as it is with a near unanimous 91 percent approval rating.

Many of the Trump administration’s bad and unpopular policies would never pass in Congress;. however bad our system is, members of Congress still have to face reelection, which imposes some limits on how brazenly they can flout public opinion. However, the quasi-legislative powers of the executive allow for these deeply unpopular policies to be carried out behind the scenes without much accountability. Because the Departments of Labor, Education, and HUD are not incredibly visible to the general public (and therefore not the top priority for most voters in presidential elections), and because Congress does not have the capacity or interest to manage them, they are effectively unaccountable—or rather, accountable only to the president.

Some socialists may see a powerful president as a major boon for our goals, since they can force through political changes more quickly. But powerful presidents allow a country to be pushed sharply in either political direction; reposing such massive power in a single individual is a hugely dangerous risk. But by democratizing the bureaucracy, popular ideas on the Left can gain new purchase in policymaking. At the same time, by diluting the power of the presidency, socialists can both protect their hard-fought policies against sudden politicized backlash from a new administration, as well as potentially diminish public fears about socialists’ secret desire to set up authoritarian Marxist-Leninist regimes.

More important than leftist strategy, however, is that this institutional shift would empower citizens to make our public administration’s policies more accountable to those most impacted, who are often the least powerful. This fundamentally democratic change would limit the amount of damage future reactionary politicians could do. And perhaps, when citizens can rely on a bureaucracy that does not change drastically every 4-8 years, they would be able to see that our country is actually capable of providing vital services to its inhabitants, and our political imaginations would be unleashed.

What would be the obstacles to trying to implement this system? Well, for starters, it’s currently unconstitutional (but the constitution can be changed, and has been numerous times in the past!) That aside, getting traction for a proposal like this would also be politically very challenging, since the presidential executive will be extremely reluctant to loosen the tight grip it has over these departments and agencies, which have been a prime vehicle for the significant expansion of direct presidential power over the past decades. The best way to introduce this idea would be to start at a state level. If it can be demonstrated to be effective at the state level, then it can begin to gain public support.

Implementing an electoral bureaucracy at the state or municipal level may seem daunting. However, California already elects, by state-wide vote, the near equivalents of Secretaries of Education, Treasury, and Commerce, as well as the Attorney General. Illinois elects the Comptroller, Treasurer, Secretary of State, and Attorney General. New York City elects a Comptroller who plays a similar role to a treasurer. Though the duties of the federal Secretary of the Treasury are qualitatively different than a city treasurer, all of these examples demonstrate that there is precedent for direct election of bureaucratic leadership. These cases are helpful as researchers can look at these different methods of selection, compare them, and see whether policy better reflects voters’ interests when bureaucrats are elected.

Implementing the stakeholder model or a state-wide electoral model would be most easily accomplished in states with voter referendums that can enact constitutional amendments. In addition, the larger the state, the larger the bureaucracy. And the larger the bureaucracy, the more convincing that example might be for the rest of the country. A state like Massachusetts—which allows for constitutional amendment by voter referendum, has few state elected officials, and has a culture of political experimentation—may be a place to gain traction for bureaucratic elections.

Ultimately, however, we will need to take an imaginative leap to apply the principle of bureaucratic elections to the federal level. Whether through national electoral bureaucracy or stakeholder bureaucracy, increasing the accountability of the executive branch by diluting the president’s mandate is a necessary change to an over-centralized system.