We Don’t Know Our Potential

A new book argues that socialism is necessary because innate differences in intelligence expose meritocracy as a sham. Socialism is indeed good, but this particular argument fails utterly.

Fredrik deBoer’s The Cult of Smart is a book about human potential: what we can all do and the conditions under which we can do it. I first read it nine months back—these days, that seems like a whole different life ago. The book was not out then; I had snagged a very early review copy, since I share the author’s publisher. I was utterly absorbed by it. It was a very strange book. It challenged my thinking. It raised difficult questions and posed somewhat surprising answers. It made me angry, but it was also right about a great many things. And it was extremely well-written. I chewed on it. And mulled. I didn’t quite know what to make of it.

Now that the book has finally come out, I look back on my past self, and I wonder why I didn’t see what is so immediately obvious to me now that it has come out: the central argument of the book is not just wrong, but wrong in the strongest possible sense of that term. It is based on fallacious reasoning. It is a mistake. An error. The whole argument falls apart completely the moment you touch it. Now, you can usually make an argument for almost anything, because so many arguments are based on subjective value judgments that are hard to prove or disprove. But unless you abandon the basic principles of logical inference, you can’t successfully make the argument of this book.

Let me do four things. First, let me give some context for The Cult of Smart to show why it’s important. Next, let me explain what its argument is. Third, let me show why that argument is such a failure. Finally, let me return to the world of nine months ago, so that I can show you why the failure wasn’t obvious to me the first time I read it, how the argument tempts people, and why I think it is so crucial for the left to understand how and why the argument is wrong.

I.

The best place to begin is with the seed and the soil. The Seed and the Soil was the working title of The Cult of Smart, and it was a good title, because it was mysterious yet accurate (the bastard money-grubbing publishers never let you go with your precious and poetic and wholly unsaleable mystery-titles). The seed is heredity. The soil is environment. An endless ongoing debate about human beings is about “nature versus nurture”: how much of who we are and what we are like is “innate”/“genetic”/“hereditary”/“nature” and how much is “external factors”/“environment”/“nurture”/“socially constructed.” We know that an apple seed cannot become an orange tree. It can only become an apple tree. But we also know that unless the seed is in healthy soil, and receives water, and all manner of other conditions are favorable to it, it will never be any kind of tree at all. Thus certain aspects of an apple tree are predetermined by the biological makeup of its seed. But other aspects are dependent on what happens to that seed.

What of us, then? We, too, have a seed, a genetic makeup that predetermines certain aspects of our physical selves. A human baby cannot grow into an adult elephant. My natural hair color and eye color have not changed since my birth. So how much of who we are is present in the seed? What is the result of what happens to us later? We know a child born to Chinese parents will, if they grow up in China, speak Chinese, and if they grow up in Germany, speak German. But we also know that a pig, raised in either country, will speak neither language. Thus language is a function of both our biology and our culture. We can say with some certainty that I was never going to grow up to be a professional basketball player, no matter how basketball-friendly the environment I was placed in from youth, because it just wasn’t in the genes. (Except: let us already notice that that last sentence, while it seems inarguably true, is, strictly speaking, false. My genes did not determine that I would not become a professional basketball player. My genes determined that I would not be tall. The requirements of professional success in basketball—a “social construct”—also determined the outcome, because basketball could operate differently in a way that would allow me to compete in it professionally—let’s say we lived in a society that had a League of 5’8’’ Lethargic Bookish Basketballers—I could have had the same genes but lived a sporting life, instead of an editorial one. This may seem like pedantry. It is not. It will be important in a moment.)

Many conservatives accuse the left of refusing to think about the questions of nature and nurture in a scientific way. They say that leftists believe human beings are a “blank slate” at birth; that who we are is entirely the product of the social world into which we are born. (I have shown before how the most prominent proponent of the “blank slate” critique, Steven Pinker, misrepresents left arguments almost every time he brings them up.) The subject of The Cult of Smart, what is called “intelligence,” is especially fraught. Some, like psychologist Jonathan Haidt, have called the left “IQ deniers” and “heritability deniers.” And over the whole debate hangs the shadow of racism.

In 1994, Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray published a book called The Bell Curve, which aroused considerable controversy, because it argued that Black people were, on average, genetically less intelligent than white people. Herrnstein and Murray began with the fact that there is an overall divergence between the scores of Black and white takers of IQ tests, and that this divergence has existed so long as the tests have been administered. (Although the gap is closing because Black people are increasing their IQs faster than white people are; from 1972 to 2002 Black people “gained 5 to 6 IQ score points more than whites did,” which should be enough to show you the racist genetic argument is garbage.) They then showed that IQ test scores are significantly “heritable,” which just means that your biological parents’ IQ test scores statistically tend to be good predictors of your own test scores, and concluded that the Black-white test score gap was at least partly genetic in its origin.

This upset a lot of people, for very good reason, because it is, well, extremely racist in the most literal sense of the term. But Herrnstein and Murray had a response to those who called them racist. They said that they were simply doing scientific research, not exercising value judgments about inferiority and superiority. Those judgments, they said, were being imposed on their research. They could not be said to be saying that Black people are inferior to white people, because they didn’t believe that a lack of intelligence made you inferior.

I imagine that your eyes may have rolled to the back of your head upon hearing that. But their argument was rather clever in a way, and for decades has provided a useful way for right-wingers to squirm out of racism charges. The Bell Curve is actually not mostly about racial differences in intelligence. That is only a single chapter. In fact, the book is ostensibly something else: a critique of intellectual meritocracy.

What Herrnstein and Murray said was this: genetic inequality in intelligence is not just racial. It exists across the population. It happens with white people too. Some are born destined to be “dumb,” some are born destined to be “smart,” and some are born somewhere in between. And while you can educate people a bit, the idea that any baby can be turned into a genius given the right supportive environment is unscientific and false.

Herrnstein and Murray’s book is in large part about the social consequences of this “fact.” They say that these days, high IQ people rule the world. We have what we think of as a “meritocracy,” whereby there is Equality of Opportunity and if you work really hard, you can rise to the top. In fact, say the authors, all that is going on is genetic sorting. The naturally smart kids are rising to the top and the naturally dumb kids, while being cruelly told they can succeed, are falling to the bottom. The result is that while there might be more “social mobility,” what is happening over time is the creation of a society hierarchically ordered by intelligence, with an elite, high-IQ ruling class and a poor, low-IQ underclass. They believe this situation will only grow worse over time, as the smarties intermarry and create more genetically superior super-babies and the dummies do the same and create even dumber offspring.

Herrnstein and Murray lament this. They lament it very deeply. They think it is a tragic state of affairs, this sham meritocracy that is in fact just the ordering of people by their genetic luck. They believe that the solution is to stop having a society stratified by intelligence, and instead to have one organized by Tradition, where people knew their places and stayed in them. They cite Aristotle and Thomas Jefferson, who believed that there was a natural order of people, and things should follow that natural order rather than having a high-IQ liberal elite in charge.

Coincidentally, the social order envisioned by Herrnstein and Murray seemed like it would probably be quite racist. (Thomas Jefferson’s conception of the hierarchy of human beings was explicitly so; he shared H&M’s perception that Black people were uneducated because they were Black and not because he employed a staff who would whip them if they touched a book.) All this talk about people knowing their places, as well as their belief that Black people were more likely to be “dumber” (they used the word dumber), combined with the fact that Murray wrote a second book on how European culture was objectively superior to African culture, makes it seem like their “non-IQ-based social order” would still have many of the exact features they lamented—truly, passionately lamented—in our present state of affairs. (Oftentimes, nostalgia for an Old Order rather than an Intellectual Meritocracy also has anti-Semitic and anti-Asian undertones as well as anti-Black ones, and the good old days were the days of quotas designed to keep student bodies WASPy.)

They were tricky, though, H&M. (The pseudoscholars, not the shop. The shop, as far as I know, is aboveboard.*) The Bell Curve did a few useful things for the conservative right. First, it attacked the “elite liberals” that conservatives think rule everything, by suggesting that their ideals of equal opportunity were a lie and they did not deserve their elite positions. Second, it reinforced the conservative belief that “human nature” tends to be fixed, and you might as well not try to do much to change society, instead you should just follow the Natural Order (which coincidentally happens to be an order in which the person making the argument will live a fantastic life and a lot of other people will have to shine that person’s shoes and make their soufflés). Herrnstein and Murray tried to prove that we should give up on attempting to make the education system fair. They suggested we had wasted billions of dollars since the 1960s pursuing the illusory promise of equal opportunity and we should basically stop trying. Finally, while Herrnstein and Murray insisted that they were simply making scientific observations rather than making value judgments—since if you think “intelligence” sounds normatively “good” and being “dumb” sounds “bad” then you’re an elitist who is part of the problem—they did provide a big pile of arguments that conveniently helped racists conclude that there is objective truth to the damaging racial stereotypes believed by many white people continuously since Thomas Jefferson’s day.

When I read The Bell Curve, I thought it was terrible and have written a careful rebuttal. But there was a tiny passage that stuck with me. Before they expound their vision for the Naturally Ordered society, Herrnstein and Murray make an interesting observation: they say that on the basis of their arguments about the causes of inequality, one could just as easily draw left-wing conclusions as right-wing ones. They admit that they themselves do not draw left-wing conclusions. But, they say, we could imagine a leftist saying something like the following:

(Please remember that this is not me the socialist speaking here, but a hypothetical socialist in whose mouth I am placing words.)

“I accept Herrnstein and Murray’s argument that genetics is a significant determinant of intelligence. I agree that intelligence is real and can be measured. I also agree with them that the fact intelligence differences are distributed genetically undermines the meritocracy’s claims to fairness, because it means that people cannot ever have equal opportunity. But I am not a conservative. I am a socialist. This means that while I accept your scientific conclusions I reject your prescriptions. To me, the fact that the intelligence hierarchy is unfair just shows that you cannot ever construct a just hierarchy. Liberals want to have a class of smart elites at the top but give everyone an equal chance at joining the club. In other words, there is still a Yale, but really smart poor kids get to go there. This is unfair, because you’ll just cluster all the genetically smart kids at Yale and leave the non-smart kids out in the cold. The conservative response to this is that we should return to the Good Old Days of Yale, before it started letting in Blacks and women, back when it was governed by tradition instead of the fallacy of merit. I, a socialist, do not share either of these conclusions. The solution is not replacing a hierarchy of talent with a hierarchy of Ancient Virtue and Noble Breeding. It’s the abolition of hierarchies! How about we don’t have small clubs like this at all? How about we give everyone the same right to participate in social decision-making, and we don’t ask them to prove themselves by any metric? It’s not who they know, it’s not what they know, the fact that they’re a person entitles them to the same dignity as any other person. Herrnstein and Murray were actually right in their position that smarts/IQ/intelligence is not a normative good. If you’re offended when they say that some people have less of it, that just means you have internalized the values of a system that says certain arbitrary capacities are Good. But this is as if we were in a society that values being able to toss the discus, and puts people in charge on the basis of whether they can toss the discus really far, and I point out that not everyone was born to toss a fucking discus, and then everyone gets offended that I’m disparaging people’s innate ability to compete at that greatest of all sports. Maybe if you shed your notion of what makes people good we could have a more reasonable debate about the genetics without it being loaded with a whole pile of implications about what the genetic findings—whatever they are—tell us about who is Inferior or Superior. The problem here is that there is a cult of discus ability worship. Who cares if discus abilities vary across the population, or even across racial groups? It’s a stupid measure!”

This argument will be a little bit of a mindfuck to some, because it’s not one anyone ever makes. When I read the Bell Curve I just thought it was rather funny; the weird theoretical “communist equivalent of the Bell Curve Argument,” would actually sound kind of compelling in certain respects, because while it would accept the bad science of Herrnstein and Murray it would use that bad science in the service of a radical conclusion that shared H&M’s hatred for liberal meritocracy but also rejected Thomas Jefferson’s idiotic bigotry.

“But of course it would ultimately be stupid,” I thought. “Because the case for egalitarian values doesn’t need to be built on bad science, and in fact, if we base the case that meritocracy is a cruel lie on the idea that human intelligence is real and genetically fixed, and then it later turns out that human intelligence is actually quite malleable through Hard Work, the case we’ve made against meritocracy will collapse and all we’ll have done is reinforce both right-wing stereotypes about human nature and the liberal belief that equality of opportunity is desirable if feasible. You’d give ammunition to the right and give nothing to the left that it did not already have, except an unfounded belief in genetic determinism.

“Good thing nobody makes this argument,” I thought. “It could sound extremely persuasive.” I should have added to that thought “…especially if made by a very good writer.” In any case, soon after finishing my article on The Bell Curve, I forgot the whole thing, including my own warning.

II.

Fredrik deBoer is a very good writer. He has written for this magazine, and obviously I believe anyone who writes for this magazine has writing talent. In fact, his work actually inspired me to pursue political writing in the first place, in 2014-2015, and may be the case that there wouldn’t be a Current Affairs if it weren’t for Fredrik deBoer. The Cult of Smart is his first book, and it’s well-constructed. The argument is clear. The sentences are crisp. It is pleasantly poetic here and there but also an argument grounded in statistics and facts. It has an uncompromising socialist radicalism and ends with a plea to liberate humankind from the shackles of capitalist oppression. Very much my sort of book, you’d expect.

But, oh my God. It’s the thing! It’s the thing! It’s the communist equivalent of the Bell Curve Argument. It’s a book-length case that intellectual inequality is demonstrably innate, therefore merit is a lie, therefore socialism is good. And of course, I agree that “merit” is a lie and socialism is good but since the first point is false for very clear reasons, those “therefores” never get to carry us logically to the egalitarian utopia.

Now, because the argument overlaps so closely with many parts of Herrnstein and Murray’s analysis, deBoer has been at great pains to emphasize over and over that he does not accept any of the racist bits of that book. You could construct The Communist Equivalent Of The Bell Curve Argument and accept the “racial IQ gap differences are genetic” piece of Herrnstein and Murray, because after all if you’re rejecting the normative value of intelligence then it’s no longer racist in your formula because the statistical conclusion is neutral rather than negative. (Or at least, this is what you say when every single person you try to explain this to goes “Uh, no, that sounds super racist actually.”) But deBoer firmly rejects the idea that racial IQ gaps are genetic. His argument is that white kids and Black kids are equally cursed by the genetic determinism that seals their intellectual fates at birth, and racial IQ score test gaps are environmental, the product of a racist society.

The actual structure of deBoer’s argument is laid out very well in a set of talking points he put out with the book. They’re not numbered in the original document but I’m going to number them here so we can follow the flow of the reasoning more easily:

- In the latter half of the 20th century the uneducated labor market collapsed and the only high-percentage path to economic security began to run through college.

- This coincided with a deepening fixation on education as the most important endeavor in human life (explicitly stated) and on intelligence as the sole criterion of human worth (implicit).

- However, only a third of American adults hold a bachelor’s degree, with many dropping out/failing out of high school and many more self-selecting out of college admissions.

- This is presumed to be a failure of teachers and their unions, leading to a full-throated neoliberal embrace of bad ideas like charter schools and private school vouchers.

- But those things can’t fix what’s wrong because they do not address the biggest part of academic ability, which is intrinsic/genetic predisposition.

- The described predisposition is about parentage, not race, describing why two individuals have unequal academic outcomes, not racial achievement gaps.

- The existence and power of genetic dispositions in academic ability have been demonstrated by literally hundreds of high-quality studies that replicate each other and that find again and again that genetic influence can explain .5 – .8 of the variation in educational metrics within the population.

- Intrinsic ability goes undiscussed because it is fallaciously associated with racist ideas about group differences in academic ability, and because it challenges the neoliberal paradigm for society—go to school and you too can be part of the professional managerial class.

- If intrinsic ability is real and powerful it means our current system cannot serve a majority of those within it; half of everyone will always be below average on educational metrics.

- What’s more, intrinsic ability undermines the very case for meritocracy itself: if we cannot determine our own position on the academic ladder, the moral argument that you get what you deserve falls away; no one can choose their genetic makeup.

- Instead of attempting to achieve equality of outcomes with bad school reform ideas, we should recognize that differences in intrinsic human abilities, of all kinds, makes the notion of just deserts in a capitalist economy absurd.

- We should thus replace the capitalist system, either through reform or revolution, with one that fights to ensure equality of outcomes through cash transfer and the distribution of power to the people.

You have to admit that it’s novel. And I, for one, accept points 1-4 completely, and so don’t think they need much discussion. I also accept point 12, Socialism Is Good, and if you removed the word “thus” I could sign onto it fully.

If we set aside the core structure of its argument, there is a lot of value in The Cult of Smart. DeBoer’s book is excellent at exposing the bad values that underlie much of the education system. He exposes the pernicious influence of the Gates Foundation and the charter school movement. He condemns those who treat certain academic fields (like Art History and Gender Studies) “as if they were worthless and their graduates deserving of economic hardship.” He questions the worth of increasing “social mobility,” a person’s ability to move up or down the hierarchical ladder. He even has long passages making the case for Medicare For All and universal free public college. (We love both around here.) The Cult of Smart has some real virtues when it talks about how absurd the college system has become. Think of the parents willing to risk prison to get their children into the University of Southern California, faking photos of them doing sports they’ve never played, etc. Every nasty word he says about Obama-era education policy, I hereby second.

There’s a quite lovely part of deBoer’s book at the end, when he’s moved away from all the stuff about innate ability and is expounding pure socialism. It is called “To Be A Person Under Socialism,” and it takes you through a hypothetical life you could live in a society built on solidarity rather than competition. I must quote it at length because it brought me great joy and it summarizes deBoer’s vision for how things ought to be different:

You are born, and at first socialism’s value is not apparent to you but to your parents. When they make the personal decision about whether or not to have a baby, they do so without the shadow of economic concerns weighing them down. They know that they will have access to the medical care necessary for pregnancy. They know they will enjoy the ability to remain close to home in the weeks and months following birth… In your early years, you attend a government-sponsored daycare center, and in time move on to a government-run preschool. You attend an elementary school that is much the same as schools are now—that is, government run, societally funded, and subject to the accountability of the local community. You learn the ABCs, the colors, counting to ten, the basics of American history (without the whitewashing), and science, and all of the things that we consider useful knowledge for a young child to learn. There is no standardized testing, as there is no neoliberal “reform” movement attempting to subject K–12 teachers to a state of constant surveillance. There is therefore no teaching to the test, and teachers are free to instruct you in whatever way they think is best to instill knowledge, skills, and values.The high school you enter is radically transformed from what it is today. The standards and requirements that are today a huge part of high school life are dramatically relaxed; aside from a few basic requirements in the major academic fields, you are largely free to choose your own curriculum. If you don’t want to take algebra II or chemistry, you don’t have to take them. Instead, you can pursue independent studies with teachers, or you can take advantage of expanded vocational and technical programs. Meanwhile, the current status of high school as a cauldron of intense and emotionally draining competition is gone. You do not have to look at your peers as competitors first. You do not get up every morning asking yourself how you will get ahead in the college admissions rat race. Because academic performance is no longer a means to secure a life at a particular income bracket, there is no class rank, no statewide standardized tests, no SAT. When you finish your high school career you judge it based not on how well you’ve prepared yourself for meritocratic existence but based on your experiences, your friendships, and your learning for your own sake. If you’d like, you can go straight into working in some productive capacity, knowing that your wellbeing is not dependent on whether or not you have a degree, and happy to feel no pressure to force yourself into more schooling. You don’t have to conform to the limited academic definitions of success, and you can choose to occupy yourself with something you are truly talented in, rather than straining to succeed in a world where your talents are marginal. You get to fit your pursuits to better match your abilities, without fearing that you are a loser for doing so. You may instead go to college, but the institution bears little resemblance to the college of today. For one, there are no competitive college admissions. Your application to college is no more complicated or fraught with implications than an application for a library card; you don’t even have to attach a high school transcript… This does not mean that everyone gets to do exactly what they want to do. Even in a fully socialized system, some people will be better at certain things than others, whether that’s being a singer or a research physicist. We as a society will have to carefully navigate the relationship between social need and ability. But all will be able to contribute something of value, as all humans have their own strengths. This is one of the most important, most humane changes of our socialist system: the definition of intelligence, and of what it means to be a worthwhile person, will expand. No longer will “smart” be the sole criterion of human worth, and no longer will worth be defined through the capitalist lens. You will find your niche, the unique way that you can contribute to and help society… Some will, no doubt, call this fantasy. They will say that such a society cannot exist. (They will ask how we’ll pay for it all, which is missing the point to an amusing degree.) They will say that we cannot generate sufficient resources to care for everyone even if we end inequality. To them, I would point to the incredible power of human ingenuity, to the immense leaps we’ve made in productivity and efficiency, and to the strength of our commitment to helping each other, even if that commitment is currently frayed by a zero-sum financial system. It’s true: not everyone can enjoy the lifestyle of the wealthy. There are insufficient resources to build everyone a private plane. I’m afraid you don’t get a Ferrari to go along with your housing and your health care. But you will find yourself enriched in the new world all the same, as you will define your worth not in material possessions but in the friendships you make, the children you raise, the experiences you enjoy. And that world— a world not of wealth but of social, emotional, and personal abundance— we can build that world today. This very day.

This is extraordinarily good, and I, too, dream about unleashing our ingenuity. (See the Conclusion, below.) DeBoer is clearly concerned, as Marx was, and the left is generally, with figuring out how to give people the conditions that make them meaningfully free. As a Marxist, deBoer is somewhat opposed on principle to whipping up those “recipes for the cookshops of the future” (a.k.a. “detailed workable plans for how socialist institutions can function”) and prefers to give us the “fishing after dinner, poetry at noon” stuff that Marx himself preferred. But though it would have been good to end with more than a reverie about the wonderful life that awaits us (and that we can build, though regrettably we are not told how), I admire the animating spirit here. It is humanistic. It appears to believe in people.

In fact, one reason deBoer gets grumpy is that critics often assume he is saying something he does not believe he is saying. For instance, he has controversially said that 12 year olds should be able to drop out of school. After all, if his Big Theory is right, some of them will just struggle there no matter what. Their best lives are elsewhere. DeBoer has written a response to those who criticize this proposal. He says that they want to keep the 12 year olds doing miserable work they hate and are bad at, instead of freeing them to pursue their own ends:

People want to know, what will they do with their lives? And the truth is that they’ll do what anyone might do with their lives. They might take long walks on the beach. They might devour books about Roman history. They might learn to fly a kite. They might help a parent take apart an old Firebird’s engine. They might get a chemistry set. They might ponder the night sky. They might pick apples. They might learn to butcher a pig. They might do many, many things, the many things that we as human beings do. The end of school does not mean the end of learning. It means the end of a particular kind of regimented, one-size-fits-all learning, the specific dynamics of which are the product of a completely idiosyncratic and directionless history that no one imagines as the only way to learn. It means the end of tests that test nothing and of A-B-C-D-F. It means liberation from the expectations of a system that no one would defend as perfect. Is dropping out at 12 the best thing for most kids? Of course not. The entire point is that most kids are not all kids. I think when people react violently to the idea of 12 year old dropouts, they are demonstrating their fealty to the Cult of Smart…

I think that’s charming. And of course I actually agree that there is excessive elevation of a particular narrow type of ability, and that skill at test-taking does not make you wise. I have very “anti-intellectual” instincts in a certain way; I am sympathetic to anyone who would prefer to have been born a duck. I also think that if a kid truly hates school, and has something they’d prefer doing, they shouldn’t have to continue, though I think the first task is to try to figure out why they hate it and make it better for them, and I don’t share deBoer’s belief that their reaction is likely due to their innate inabilities.

I must say, though, that I don’t think people who react with horror at his proposal to let 12-year-olds drop out are actually just showing fealty to a cult. I think they have a very real concern, which is that for someone who talks about what could happen “within our lifetimes,” he has not noticed that any “12-year-old dropouts” we can conceive of happening reasonably imminently would probably be very bad, since it would just shuffle the “not cut out for college” ones into their Amazon warehouse jobs. Notice that the 12-year-old dropouts above seem to live in the hypothetical socialist utopia, not in the 2020 United States. Theirs is a world where you can do anything, and you don’t have to be like anybody else, and if you want to spend your life building kites and flying them, that’s fine, because housing is free and so are food and healthcare, and kite-making materials are free for the grabbing down at the communal supplies warehouse. If you want to go back to school later, you can, because we have lifelong free classes on every subject accessible to all, and there’s no stigma to leaving school for a few years, so “dropping out” doesn’t mean what it does in our society. But we must be careful here: this is good if we do all of this. In the socialist dreamland to which we march ever forward, 12-year-old dropouts might not really present a problem (except for the problem of not teaching people critical things they need to know in order to participate in democracy and understand what is going on around them). On the other hand, if we let 12-year-olds leave existing schools now, we will just expand black market child labor.

There are probably 50 more thoughts and arguments from this book I could muse on. As I say, it’s highly original. But it is ultimately built around a core argument, and I want to deal with that main thread. DeBoer calls the book a “plea for the untalented,” and the gist of it is: Student abilities are substantially genetically inherited and therefore it is a fool’s errand to try to achieve equal educational outcomes. If that claim is not demonstrated to be true, we’re left without the centerpiece of his case against meritocracy, and therefore the case for our beautiful socialist utopia.

III.

I have asserted repeatedly that this argument will collapse when we touch it. Let me now show you exactly how it does.

First, to watch the house of cards start to wobble, have a look at the opening anecdotes from an article deBoer published in the Chronicle of Higher Education called “Some Students Are Smarter Than Others (And That’s Okay)” (writers don’t pick article titles, but deBoer wrote that he was pleased with this because it would “troll” people, i.e., upset them). DeBoer gets Chronicle readers to start thinking about the issues of the book by citing an experience he had teaching students:

As I approach the door to class, I notice that one of my students waiting outside is crying, while friends comfort her. I know better than to say anything to her directly; the last thing an emotional undergraduate wants is an instructor offering consolation. After class I caught up with one of her friends to check if everything was alright.

“It’s just first-year engineering,” she said. “Everybody cries.”

I was a little concerned, and a little curious, so I poked around a bit and talked with a grad student I knew in mechanical engineering. He told me that only one in three students who started as an engineering major would finish with the degree, and that early courses in the major were actually designed to be “weed out” classes, meant to compel students to drop the major and choose another. Why? Because the rigor of the engineering programs was so high that a large percentage of students was guaranteed to drop out eventually, and it was far better for them to do so early, before they had accumulated a lot of credits.

What had seemed like cruelty to me was, in fact, an act of mercy, an artifact of a pragmatic and necessary acknowledgment that not all students possess the underlying ability necessary to flourish in some fields. In time I would learn that many college classes, such as calculus and organic chemistry, function in much the same way. And I grew to think that rather than representing a failure of educators to do their jobs, these classes, which screen out students, perform a necessary if unfortunate function for colleges dedicated to training young people for their futures. Experiencing these moments as an educator, and observing many others as a student, deeply influenced my thoughts on how teaching does and should function in the real world.

[The pull quote on the article is: “What had seemed like cruelty to me was, in fact, an act of mercy.” We will return to this.]

Now, deBoer could have picked any moment that “deeply influenced” his thinking on how teaching functions. He picked this one. He tells us explicitly that it is illustrative. We are meant to draw an inference from it. How is that inference drawn? Watch:

- (Male) professor sees (female) student crying.

- Professor asks (2nd female) student why 1st was crying. Is told she is in first year engineering. Professor finds (male) student to explain what’s going on. He tells the professor the department is not just “rigorous” but actively tries to “weed out” students who do not “possess the underlying ability necessary to flourish” by “compel[ling]” students to drop out of the program and choose a different major sooner rather than later.

- Professor says that this data (female student in tears—though no first person testimony from her—plus explanation that she is in engineering and thus under extreme pressure from a program explicitly designed to encourage her to leave it), combined with other similar data, helped him form a conclusion: students have differing abilities. Some just can’t cut it. It’s impossible. No matter what, they will fail.

- THUS, it is better to knock these students off early. If 1/3 of program participants will ultimately drop out, it is far better that the 1/3 drop out on day one than for the dropouts to be spread over the course of years. If day one is a real motherfucker that makes you cry and feel stupid and incapable and want to give up all of your dreams and ambitions and go do something “easier” better suited to your dumb brain that couldn’t hack it with the big boys, this is not abuse. It is mercy. You are being given the opportunity to be your best self, by being shown that your ideas about what you could accomplish were wrong. You should be thanking them, really. Pain was inflicted upon you out of compassion. Sometimes you’ve got to be cruel to be kind.

I, um, I don’t know if you’ve noticed that there seems to be something a touch psychopathic in this. Given how people are very capable of constructing convenient rationalizations for cruelties that they also secretly relish inflicting (it hurts me more than it hurts you), we should be deeply, deeply skeptical of arguments that Actually, what seems like obvious transparent cruelty is really kindness, mercy, love. Actually Sweatshops Are Good. Actually We Needed To Nuke Those Civilians. This tends to be a right-wing position: the world requires cruelty in order to be just, and those who are too compassionate, whose hearts bleed too much are Hurting The Very People They Are Trying To Help. You spank the child for its own good, not because you like hitting children. Your class makes a young woman burst into tears, not because you want her to cry, but because she must cry and suffer so that she may prosper in her correct discipline of Art History or Gender Studies or Sociology rather than engineering, for which she is innately ill-suited.

Now it’s time for me to take a turn as the Professor, and the class we’re taking today is called Logical Inference 101. We begin with a pop quiz. Please answer the following question: from the fact that a student is crying and you are told the engineering program tries to weed out students quickly by making them cry, is it rational to infer that the engineering program probably is weeding out students based on innate ability?

If you answered “No, of course it fucking isn’t,” congratulations, you get to stay in the class. If you answered “Yes,” I’m sorry, you’re weeded out. You should major in rhetoric or something. Go cry about it.

Now, if you are a political conservative, when you encounter arguments about the moral necessity of hurting people, you may drift toward them without examining too closely whether they hold up under serious scrutiny. If, however, you are a person of leftist sympathies, or simply have a functioning moral compass (the two often amount to the same thing), you might wonder if there is an alternate possibility: perhaps the school system is actually just not serving its students very well.

What if the argument that the male student made, and that deBoer and the engineering department believe, is actually not true? What if it’s just a story they tell? Okay, based on the fact that 1/3 of engineering students will ultimately drop out, they think they should find that group early and dispose of them ruthlessly. But why are 1/3 of engineering students dropping out to begin with? “Well, because they don’t have what it takes.” And how exactly do you know that, might I ask? How do you know anything about the woman you saw crying in the hall, especially considering you never even spoke with her? (By the way, less than 20 percent of engineering students in this country are women, and if we were curious social scientists we might wonder whether this woman’s experience could tell us something about why that is. If we talked to her, we might find out!)

I’ve actually taught students myself before. Only briefly, and only as a TF doing a section, but I was good at it (false modesty is annoying; the kids like me, I liked them, and they learned a lot. There are millions of things I’m awful at but teaching suited me really well). I, too, have a representative anecdote from which I could extrapolate beyond what is justified. My anecdote is: the most brilliant student in my class was also the worst student. She was Black and from a working-class background. She had a unique mind. Let me tell you: you do not get to Harvard as a working-class Black student unless you are some kind of one-in-ten-zillion weird genius, because you are going to be competing against people who literally hired professionals to write their college essays for them, and whose parents bought a building for the school, or who have been taking private violin lessons from the world’s finest player since the age of three, or whatever else. This is one reason why critiques of affirmative action are so grotesque: they stigmatize Black students as illegitimate entrants when the opposite is the case. They are the students to whom the “intellectual meritocracy” most brutally applies. The more marginalized you are, the more you have to depend on your talent, rather than money, connections, and that unflappable self-confidence that comes with a ruling-class upbringing. A Harvard student who is Black and female and working-class? Yeah, she’s going to be extremely smart.

When my student wrote papers, they were always among the three or four best papers in the class. (Not the best papers; I am here to tell the truth, not elevate her to mythic status.) That is when she wrote papers. But oh dear God, the struggle to get the papers. It was comical, really, because we were both very similar in many ways. Disorganized, chaotic, chronic inability to get the assignments in on time. We used to laugh about it in office hours, because to me it was funny. She got a good grade from me, not because I “altered my expectations,” but because she learned a ton of stuff from the class and came to office hours not to beg for extensions (as some students did) but to engage with the stuff I said in the class. Who cared if the fucking papers were late? That’s just rule-following, and I wasn’t teaching a rule-following class, I was teaching knowledge, and my evaluation was based on whether you knew what I was teaching you.

That was my approach. It was not, however, the university’s. My student was in big-T trouble. Her grades in general were horrible. She was being threatened with expulsion if she didn’t shape up. This made her terribly stressed out and afraid, because she had worked incredibly hard to get where she was and to lose it would be devastating. No matter what, she was going to be left with a set of bad grades that would follow her into the job market. I could already see, to my horror, those subconscious words forming in the mind of a future employer looking at a resume: Couldn’t handle it. Would have been kinder to show her the door at the start.

And I want to scream, because it’s the literal inverse of the truth. What actually happened was an institution was too screwed up to actually nourish one of its most promising students. Instead of figuring out what she needed and giving it to her, it punished and scared her, making her perform even worse because of the pressure, and setting off a disastrous cycle. It’s such a joke to me when conservatives say college students are coddled. Coddled? You kidding me? They’ll give you a room full of cushions or five Deans For Inclusion, but as far as actually helping you learn stuff and keep your life together, you are as alone as you’ve ever been in your life up until that point.

I think many, many teachers have similar stories. I know David Graeber has one. A working-class woman in his graduate class at Yale was brilliant, but she just could not bring herself to fill out the registration forms. That may sound ridiculous to you, but I was actually the same: every single year I had to pay a huge penalty for submitting my registration forms months late. I managed to make it work by bribing my way out of the situation (by which I mean just paying the giant accumulating late fees), but Graeber’s story ends tragically: the student was kicked out of the program. Over some forms! In fact, Graeber says his own experiences in grad school were similar. He had a hard time despite having the makings of a great anthropologist:

As one of the few students of working-class origins in my own graduate program, I watched in dismay as professors first explained to me that they considered me the best student in my class—even, perhaps, in the department—and then threw up their hands claiming there was nothing that could be done as I languished with minimal support—or during many years none at all, working multiple jobs, as students whose parents were doctors, lawyers, and professors seemed to automatically mop up all the grants, fellowships, and student funding.

All of this is to say that as a leftist, rather than a conservative, your instinct when seeing the Crying Engineering Student should be: how is the engineering department doing its job so badly? Some students are always going to leave a program, because they lose interest, and yes, some may not “be able” to do the work (more on this shortly), but since we know that the number of ways in which our society makes it difficult for those who could do the work under the right conditions given the right support, we should probably ask first about how to create those conditions rather than to justify intentionally adding factors that will discourage them from succeeding. The conservative asks: what is wrong with this person that they are crying? The socialist asks: what are the causes of this person’s pain and how can we ameliorate them? Do we not think there is a chance that this “weeding out” process, which will inevitably be hardest on the students to whom the college environment generally is a difficult transition (those whose parents didn’t go to college) will not actually figure out who has the “aptitude” but will instead figure out who can do the best in the program as it is structured? The buried assumption is that the program as it is structured is the only way, or the best way, to teach engineering. Assumptions are not evidence, though. In fact, engineering programs are different across countries, and dropout rates vary widely. Levels of financial support, the culture of the program, and levels of preparation provided beforehand are all factors that might be at work. But we have to investigate that empirically.

So the first sign of trouble for the whole argument is that the illustrative anecdotes deBoer exhibits for us cannot and should not lead to the inferences that he drew, because they equally well support the exact opposite conclusion, which is that instead of figuring out what it would take to get as many interested students as possible through the engineering curriculum, the university is already operating on deBoer’s theory of Natural Aptitudes without having actually proved it.

I say they haven’t proved it because, as we are about to see, you can’t prove it. Let me tell you when we will have shown something about “fixed limits” on an aspiring engineer’s capacity to do the work: it will be when we have let that person take decades of completely free classes on engineering, taught by every conceivable pedagogical method, and we have no complicating factors in their lives that might make school harder (like having to survive under capitalism, or dealing with trauma, death, and divorce). When we have given students a boundlessly kind, supportive engineering program, that lasts as long as they need and is structured around them with as many of society’s resources as possible put toward its perfection, rather than a brutal one that tells them that 1/3 of their classmates are incapable, then maybe we will know their “natural capacity” for engineering. We will also have to have verified that this program isn’t misogynistic and that we have tried to fix elements that might cause certain students to be more likely to not want to participate.

But, no, even then we won’t know about “potential,” because it could still be that a few small misunderstandings of crucial concepts are blocking a given student from moving forward, but if they had gotten past those misunderstandings there was no fixed factor in their brain that meant they couldn’t continue. (The misunderstandings are not necessarily in themselves a fixed factor, because it could be that they could understand better if we knew a better way of presenting the information, but we don’t). And even in the case that society puts “as many of its resources as possible” toward teaching, we still don’t know if it could have done better, because “possible” will always be a political choice. I tell you what, how about this: when we have built an entire society around teaching Arthur Goldfarb of Altoona, PA to be the engineer he aspires to be, when literally every person’s every task is in some way in service of that goal, when every technological innovation is designed under a “help Arthur be an engineer” mandate, when Arthur tries his absolute best for 24 years but still can’t master the material, then let’s conclude that it was just not in Arthur’s genes. Except, of course, we won’t even be able to do it then. Because Arthur likely failed due to the pressure.

Here we approach the central fallacy that is at the heart of the book’s case, and will set the whole argument “collapsing like a flan in a cupboard,” to use a colorfully bizarre phrase of Eddie Izzard’s. The question is: by what method can you reach the conclusion that a distribution of inequality we see in our society is the “result” of “genes” “rather than” “environment”? And the answer is, you can’t, because it’s the wrong question.

Let’s talk about how social scientists have tried to examine “heredity.” It is not by understanding genetics. DeBoer admits that he is an amateur at the science of genetics itself. The argument is actually that you don’t have to understand genetics to understand that something has genetic causes, because you can statistically control for the environment. Here, listen to famous psychologist Eric Turkheimer, who is cited by DeBoer:

“…one can use straightforward statistical procedures to estimate the proportion of variability in complex outcomes that is associated with causally distant genes, all the while maintaining a state of near-perfect ignorance about the actual causal processes that connect genes to behavior.” (Emphasis mine, of course.)

In other words, if I see that across every civilization on earth, tall parents tend to have tall biological children, and this is true even when those children are separated from their biological parents at birth and raised with short parents, then after amassing a sufficiently satisfying body of evidence, and having considered all other possible explanations, I may conclude that height is, at least partly, a product of genes. Other post-birth factors might affect it (e.g., nutrition), and we might even admit that a great deal of variation in how tall you’re going to be is a product of your environment, but having tall parents still influences the chance of whether you’re going to be tall. Same with baldness. You can go bald for lots of reasons, but if biological families with lots of members keep producing bald children, no matter the environmental variations, and biological families without bald members seem never to produce bald members, safe bet there’s something in the genes. Same with skin tone. If people with darker skin produce darker-skinned babies, etc… And the argument is that you don’t have to know anything about genetics to know that it is genetics. Let the geneticists figure out the actual mechanism. The point is, we have isolated the area in which the cause lies.

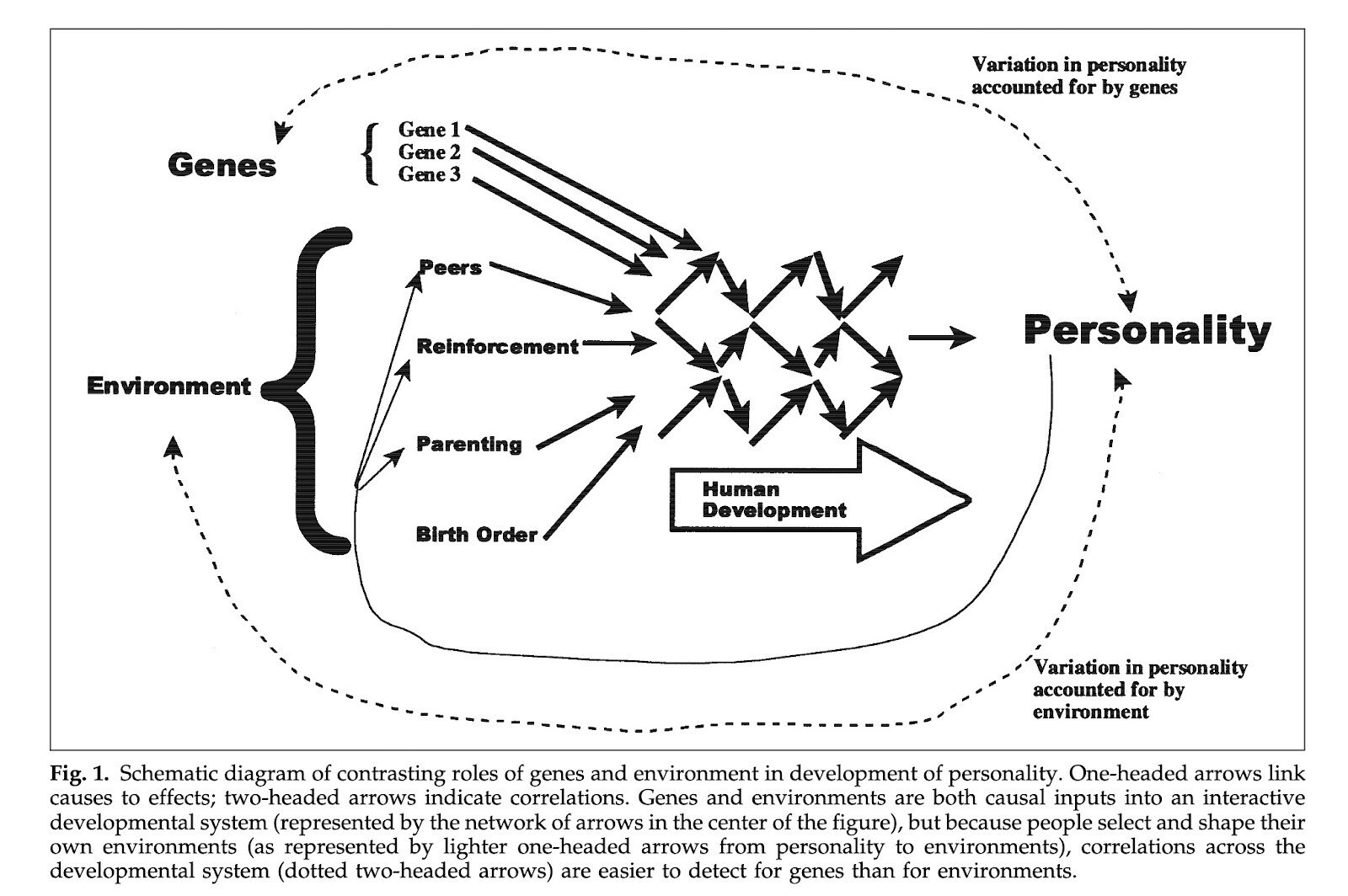

In practice, there are major debates about the degree to which we can, in fact, do this, because it is almost impossible to study changes in “environment” in precise ways, and serious behavioral geneticists admit how deeply difficult it is to actually draw hard conclusions because things influenced by genes then influence the environment, which in turn influences the display of things influenced by genes. See this diagram of the whole mess from Turkheimer:

The result is that it’s actually not useful to say things like “genes are responsible for 60 percent of your intelligence,” because when causes interact like this it is not meaningful to divide their relative contributions into percentages. See this diagram:  from Moore & Shenk: “The Heritability Fallacy“

from Moore & Shenk: “The Heritability Fallacy“

The Murray-Herrnstein/deBoer argument tries to apply the “heredity versus environment” framework to intelligence. IQ test scores, academic performance, etc., are strongly correlated between biological parents and children regardless of how those children are raised or whether they even spend five minutes of their lives around those parents. Take the child of high-IQ rich parents and place them with a low-IQ poor family (just saying “low IQ” makes me cringe, by the way, but I’m giving you the argument on its own terms before we put a firecracker in it and blow it to kingdom come). We have therefore controlled for environment, by trying kids in different environments and noting what doesn’t change, so we can’t say “poverty” causes IQ score gaps, and the mushy feelings-based left, who can’t handle Facts and Logic, are clinging to the insistence that poverty is the cause of educational testing gaps when actually it’s genes. (I am not going to dispute these findings for the purposes of examining the argument, because the central point here will be that even if the studies deBoer cites are accurate they do not lead to the conclusion he thinks they do. But I am not claiming that the heritability studies themselves are accurate.) Let us check whether the basic reasoning actually holds up, or whether it is mere Cupboard Flan. Let us return to our soil, and seeds.

Let’s take a particular closed environment: indoor plants. (I own no indoor plants. These are the hypothetical ones I would own if every plant I touched didn’t immediately die.) My baby cactus grows to one foot, my orchid grows to two feet. But maybe that was just those particular individuals. There will be variations if I get more. So I get lots more baby cacti of the same species. Lots more orchids, also of the same species. Always the same: one foot, two feet, give or take. I give them the same amount of water, the same amount of plant food, the same everything. Identical shared environments. One foot, two feet. The cactuses look weak. The orchids are thriving.

Now, I want to know whether the difference could be environmental in origin. So I vary the environmental influences: I change the amounts I water them, the amounts of plant food, the amounts of sunlight. But there are commonalities that persist across these environmental variations I try. I therefore conclude that the differences in height are heritable, thus genetic, and that the orchid is simply better suited to survival. A baby cactus cannot outgrow or outshine an orchid. They have a Nature.

But then I realize something: I have tried a number of environmental variations (more or less water) and concluded that they don’t matter. But these variations took place within a shared environment that was consistent across all of the experiments. I have not changed that shared underlying environment. What if I took them outside?

I take my plants outside. Something shocking happens. My orchid grows to the same height. My cactus now grows to the same height as my orchid! What?! Two feet, both plants, every time. It turns out my cactus loved having lots of sunshine, and my orchid had already topped out and didn’t benefit from any more sun. At a certain point, my orchid even wilts while my cactus endures. (It helped that I briefly forgot to water them, because as it turns out orchids and cacti require different amounts of watering). I bring a second baby cactus outside, totally forget to water it, and it grows to ten feet! Where will the damn thing stop?

What has happened to my theory? Two things: first, I have not lost the part of the theory that says biology has a role in determining plant height. Orchids and cacti do behave differently under the same circumstances, depending on those circumstances, and certain changes in circumstances will not alter that difference. What I have lost is the ability to look at the difference between the heights of the cactus and the orchid and say that the cactus is “predisposed” or “naturally” shorter than the orchid. If it is predisposition, it is predisposition given a particular shared environment; the background thing we have not varied. Actually, in a different and more conducive environment for the cactus—with the correct type of nourishment this time from its caretaker—the cactus was often taller than the orchid. It was a mistake of reasoning to conclude that orchids have an “innate” tendency to be taller than cacti. Only if you assume that the shared environment is unchangeable. And we can be misled by the fact that we did vary various environmental factors (water, food, etc) while missing that there was one big one that we were not varying.

DeBoer says: “As the environment is equalized, the importance of genetics grows.” He, too, cites plants: if you plant one in bad soil and one in good soil, the differences between them might be genetic or soil based. If you plant them in the same soil, the differences between them will be genetic. True, but remember what we’re talking about: the differences in outcome in particular, and the differences within a given shared environment. Change the equal environment for a different equal environment that affects both plants differently (trading indoors for outdoors) and your whole finding of capacity might go in the other direction.

Getting to humans. Suppose we see that some people are shy and tend not to talk in groups. Others are loud and tend to jabber. After observing a million people, across every culture, we find that jabberers are always the biological children of jabberers, and the meek are always the biological children of other meek people. Even if you switch the babies at birth! Having a meek person raised by a jabberer won’t make you into one, any more than a white child raised in a Black family would have their skin turn darker. We controlled for environment, by trying genetically similar children in different environments, and concluded that the environmental variation wasn’t causing the outcome.

So we conclude that whether a person is shy is genetic. And when the mushy gushy liberals say that no, environment matters, we laugh at them and say they are “blank slate” theorists who do not understand that human nature is fixed.

And yet: what if something happens to change the shared environment that was the same across every experiment? The thing we hadn’t varied. What if we introduce a new way of doing meetings that is supposed to make people feel comfortable speaking when they otherwise would not? (My one innovation in pedagogy was an attempt to make this happen.) What if we taught jabberers to step back a bit and encourage others to talk? What if we adopted a “progressive stack” that tried to make the conditions necessary for the “naturally” shy people to speak?

Let us say that in our hypothetical, a strange thing happened. First, by changing the structure of meetings, we changed the balance of who spoke. But there was more. After getting to speak in a low pressure environment a few times, the shy people tended to come into their own. The jabberers actually began to speak less than the formerly shy people, because the jabberers realized that shy people had interesting things to say, having spent more time listening. Or something; it doesn’t really matter what it is for the purpose of reaching the conclusion, which is: even though “eagerness to speak in meetings” was a 100 percent heritable trait in one society, in that it was completely predicted by who you were born to biologically, in a different society it was not heritable at all, meaning there was no statistical correlation whatsoever between a given trait possessed by your biological parents and the likeliness of possessing that trait in yourself.

What the hell?! How did something that obviously seemed genetic suddenly not seem genetic at all? Because the consequences of genetic variances can be environmentally determined. The emergence of a trait that is statistically “heritable” might be entirely caused by environmental influences. It might be true that some people are “born with the genetic predisposition to be shy within one environment” but that fact in and of itself doesn’t tell us a thing about whether they’ll be shy in all environments, because over the course of life in a given social environment, the naturally shy people, who were naturally shy because of a genetic cause, could all turn into jabberers. “Inherited shyness” may mean “inherited shyness within an environment that discourages participation,” but mean literally nothing in an environment that encourages participation.

It can actually be put even more starkly than that. The way “heritability” is calculated, “being circumcised” can be “heritable” because the likelihood of being circumcised is highly correlated with a chromosomal difference. As Noam Chomsky explains, the treatment of “heritability” in Murray and deBoer is an “elementary error” that results in making statements that sound scientific but are actually “meaningless”:

One conclusion drawn is that IQ is heritable; according to Bell Curve author Charles Murray, 60% heritable, which means that “60 percent of the I.Q. in any given person” is “heritable.” Murray’s statement is meaningless, but presumably he is intending to convey the idea that 60 percent of the I.Q. of a particular individual is determined by the genes. Many others have drawn the same conclusion, based on an elementary error that has been repeatedly pointed out, among others, by Robert Wright. He correctly observes that a trait can be highly heritable whatever its genetic component; say, 100% heritable with no genetic component…

We can see easily why “heritability” does not measure what’s “in” our genes. Take “intelligence,” and let’s assume we’re talking about IQ test scores. DeBoer notes the existence of the “Flynn effect,” a very interesting phenomenon whereby performance on IQ tests goes up every generation. In fact, over just 70 years, British children’s average scores rose by 14 IQ points. This effect is not attributed to changes in genetics over that time; it’s not that you have Smart Genes that your grandparents didn’t have. There are lots of different explanations posited (nutrition, interaction with technology, every generation building on the learning of the previous generation, etc.), but they are about the shared environment.

DeBoer doesn’t note, though, that this has very serious implications for his thesis. Ten generations from now, children with no important genetic differences from today’s generation could be scoring, on average, twice as high on the same tests as we took. Clone a person born in 1910, raise them in the contemporary world, and the clone will probably do much better on the same test than the original person who took it in the 1920s. Same genes, giant increase in intelligence. We do not have any idea how far this rise in IQ scores could go as the world continues to massively change around us.

If that’s true, though, it means that I do not necessarily have a genetic “inability” to do a particular thing simply because no matter how hard I work, here in 2020, I cannot master it. If I (meaning the genetic me) had been born 20 years later in a hugely different shared environment, I might be able to do it. James Flynn, for whom the Flynn effect was named, says that our IQs have risen over time because our society has put on “scientific spectacles,” and people now “reflexively organize information into abstract categories and discern complex relationships between concepts—the very skills that intelligence tests assess.” But the change has not come about due to genes, because our genes have not changed.

When we think about schools, we should see the implications. In a school that is “sink or swim,” that is, the test is given to you and we measure your performance, and everyone gets the same level of instruction, and everyone has had the same environmental background, those who have whatever genetic predisposition makes people “natural” test takers will do better. Those who lack these natural predispositions will fail. Scores will be highly heritable; that is to say, the genetic factors will be “coming out in the results.”

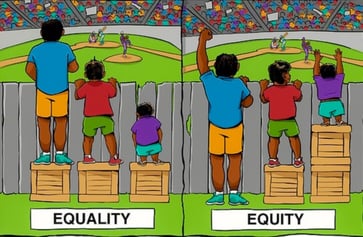

The implication for school policy is this: you will know nothing of whether there are natural inequalities of aptitude unless you have a system designed to focus on the least naturally school-inclined person (and you’ve developed human society as far as you can develop it, to see where the Flynn effect stops). The kids who do the worst must be given the best, or at least forms of instruction that better suit their talents. Now, you might say, “even if we gave everything we could, and even if the kids with the least genetic predisposition were given the most assistance, those with the genetic predisposition will always come out top.” Could be. But not necessarily. Could be that it levels off and at a certain roughly equal point everyone tops out. Could also be that it reverses. We are certainly not capable of proving this now, with our existing philosophy of schooling, which targets the creation of equality rather than equity (meaning giving everyone the same stuff rather than tailoring it to their individual needs).

The equality/equity illustration shows things well. Assume height variances are entirely the product of genetic factors (although of course it actually might well be the product of some kind of environmental injustice). If height is hereditary, “ability to see the game” is therefore also hereditary in the “Equality” (liberal meritocratic) situation. In the “Equity” (socialism) situation, ability to see the game is not hereditary, meaning that the variation is not predicted by genetics, since there IS no variation in people’s ability to see the game.

Actually, I hesitate to use this image, because I worry that it will lead some people to the exact conclusion I am trying to disabuse them of. You may look at this and think “the tall person has a natural genetic advantage but if we help the short person they can get to the same level” and indeed that’s part of the original message of the image. But even the term “natural genetic advantage” is mistaken, because as I say, the height differences could be environmentally caused even if hereditary. Consider the following situation:

A is a situation in which each person receives an unhealthy diet growing up. All of them become the same height. B is a situation in which people are given the average contemporary diet. C is one in which they all receive a nutritional supplement called “Nutri-Grow.” Now the interesting thing about Nutri-Grow is that if you’re the sort of person who would be short on the average contemporary diet, it makes you much taller. On the other hand, if you’re taller on the average contemporary diet, it makes you shorter. What we can see here is that it is not in fact accurate to say that the person on the left is “naturally” or “innately” taller. That was true given a particular set of environmental exposures. But change the nutrition and we flipped the outcome. If Diet B yields the order 1-2-3 and Diet C yields the order 3-2-1, and a diminished diet means everyone is equal and height isn’t hereditary at all (because genetic difference doesn’t explain variation in height, as there is no variation), then who is “naturally” or “innately” tallest? The answer is that the question isn’t meaningful, and the only genetic conclusion is, as Turkheimer says, that “people who are more similar genotypically tend to be more similar phenotypically” (that is true for Diet B and Diet C, though genotype did not affect the relevant phenotype in the starvation situation.

DeBoer knows everything I’m saying. He says explicitly: environments where everyone is treated identically will bring out genetic correlations, and he critiques the philosophy of “equal opportunity,” saying it doesn’t recognize individual different predispositions. But:

- Having a philosophy of equal opportunity does not actually result in real equal opportunity, as we see in the case of women and minority students who are systematically drummed out of STEM by subtly (or unsubtly) bigoted professors.

- Even if equal opportunity could and does exist, the correct conclusion is the opposite of what deBoer thinks. He thinks the “genetically caused” inequalities of outcome, which emerge within a system he believes will magnify those inequalities, reveal the upper limits of a student’s natural aptitude. They do nothing of the kind. All they show is that without building each student the personalized school system that fits them best, whatever small genetic differences exist (which may have nothing whatsoever to do with intellectual capacity) will determine the rank order of “aptitude.”

This is one reason that the Bell Curve’s racist arguments are racist. Chomsky pointed out in response to the book that actually, finding that IQ is “heritable,” and even finding very strong correlations to the bundle of random traits we lump together as “race,” in and of itself, is consistent with the hypothesis that Black people are all genetically born with superhumanly high IQs. It could just be that superhuman intelligence can also be stamped out in given environmental conditions, such as a racist society. My chaotic brilliant student might be an individual example of some “genetically natural super-intelligence” clashing with the structure of the society in which she exists; the very magnitude of her “natural” intelligence might have resulted in her being ranked a failure, if hypothetically the social environment she was in was not actually set up to identify intelligence but rather the most naturally diligent automatons who are good at getting their work in on time.

Obviously, because race is a social construct, I do not believe that there are actually any intelligence differences that can occur because of your race, but the point here is that, like a cactus might have greater potential height in one environment but look “genetically predisposed to shortness” in a different environment, a racist society in which people are treated differently from birth on the basis of racial categories is a huge variable that you can’t actually “control for,” and thus you can’t at all draw conclusions about what the differences between people would be if you lived in a nonracist society.

I am not critiquing deBoer there, who rejects racist arguments about intelligence. But what he doesn’t see is that he’s using the same faulty reasoning himself. If we have a school system that punishes those who think in different ways (and fine, assume it’s technically because of some gene), and doesn’t provide them with the support they need to succeed, then the fact that the biological children of people who failed in school tend to fail in school does not tell us that they will fail in all schools, just that they will fail in ours, because of the ways our schools and societies are constructed. In fact, for all we know, outcomes could not only be equalized, but reversed, if we built a library on every corner in poor neighborhoods and staffed every library with brilliant, kind, funny people who would make learning a joy for anyone who stepped in the door.

Now, note, because this is important: by saying that there could hypothetically be a genetic source of an observed inequality that a different environment could change, I am not saying that the genetic source is a “diminished” intelligence that could be “compensated for” some other way, by providing “help.” No, the claim is far stronger than that: as I say, it could be an increased intelligence. An extraordinary-sounding thing about behavioral genetics, which deBoer cites, is that every observed human behavior is “heritable,” which just means that “on average, people who start out more similar genetically wind up more similar phenotypically.” So, owning a dog is heritable, but if you lived before the domestication of the dog, you could have had the same genes but not owned a dog.

So you have to critically examine every part of not only what the school system is doing, but also every part of a person’s life that could be transforming some extremely minor heritable factor into a giant full-blown difference in outcomes. To see whether you could achieve equal outcomes when there are heritable traits affecting the outcome, you do not equalize the environment, you make it unequal in the opposite direction by giving those with the heritable trait the things they most need.

DeBoer knows that while we say we do this, we do not in fact do it. The American public school system, as he has acknowledged, is not a place that cares about tailoring itself to the needs of each individual child. Our institutions with their ideology of “meritocratic equality” (where the rules of the game apply equally to all and we apply the same test to see who succeeds and who fails), have no actual interest in trying to achieve academic “outcome equality” (where the rules do not apply equally to all, it’s to each according to their need, because we want everyone to pass the test). In a system based on the latter principle, if a chunk of kids were consistently unable to pass the test no matter what, you might conclude it was hopeless. But we’re a long way from “no matter what.” As deBoer knows full well, our school system often just tries to sort people by whether they possess desirable traits for future work in the capitalist superstructure, instead of taking seriously the challenge of helping everyone succeed academically.

Another way of putting this is: DeBoer says that we have a competitive system that rewards those who possess aptitude. And the people with the most intelligence are supposed to win and take their place in the intellectual hierarchy. (All of this is gross oversimplification of how the world actually works, by the way, but nevermind that for now.) But, he says, the competition is unfair, because not every student can be equally intelligent, due to their genes. But he is wrong. This is conservative folk wisdom, not valid scientific inference. The reason they might not be able to be “equally intelligent” might actually be due to the combination of some small genetic thing with the false equality of the meritocratic teaching system, which says it tries to teach but largely just tests for whatever traits are already possessed. It might well be that all students could reach an equal standard of “intelligence” if the teaching system was built around solidarity rather than competition. DeBoer says, roughly, smash the meritocratic hierarchy, the natural abilities are obvious and we cannot change them. But there is another way to be a socialist here, by saying “smash the meritocratic hierarchy, natural abilities are not obvious and the current system assumes some people will fall short of the top rather than everyone reaching it at once.” We will not be able to make statements about our capacities until we have tried socialism.

Here, let me drift a little bit into speculation, and say some things I am less sure of but that I think are provocative and interesting. All of this may mean that capitalist realism is hampering the advancement of behavioral genetics. Remember the parable about the fish who doesn’t know what water is? Well, capitalism is the water. We look at all the things that could be creating differences in students’ measured intelligence: family structure, poverty, etc. Well, but what if we’re doing what I did with my plants, and keeping them inside? Perhaps taking them outdoors and watering them properly—i.e., transitioning to a post-capitalist economy and schooling based on post-capitalist values—would radically alter the heritability of various traits, the way creating means of equal participation alters the heritability of jabbering. If indeed the search for how to unleash human potential has been affected by the assumption that “capitalism is held constant,” it is a good example of how economic systems and the ideology they produce can shape the direction of science, and vindicates Marx and Gramsci.