The Tuttle Twins and the Case of the Really Bad Libertarian Propaganda

The Right gets ’em while they’re young.

Anyone with kids in their family knows that one of the great things about them is their bottomless gullibility. Until critical thinking abilities (sometimes) develop in later life, children will believe any hilariously phony lie you tell them, for example that a minor deity is so excited to get their disgusting baby teeth that they leave printed American currency for it, with the Treasury Secretary’s name on it. It’s the dumbest thing in the world, but I and probably you believed it for years.

Sadly, some would abuse this adorable nature of kids for sleazy purposes. There’s a whole genre of apocryphal quotations by leaders of authoritarian movements, saying some version of “Give me the child for seven years and I’ll give you the man,” meaning those formative early years can shape beliefs that endure through adulthood. Jesuit leaders, Lenin and others are alleged to have said similar lines, but regardless of the exact provenance, the point is clear enough.

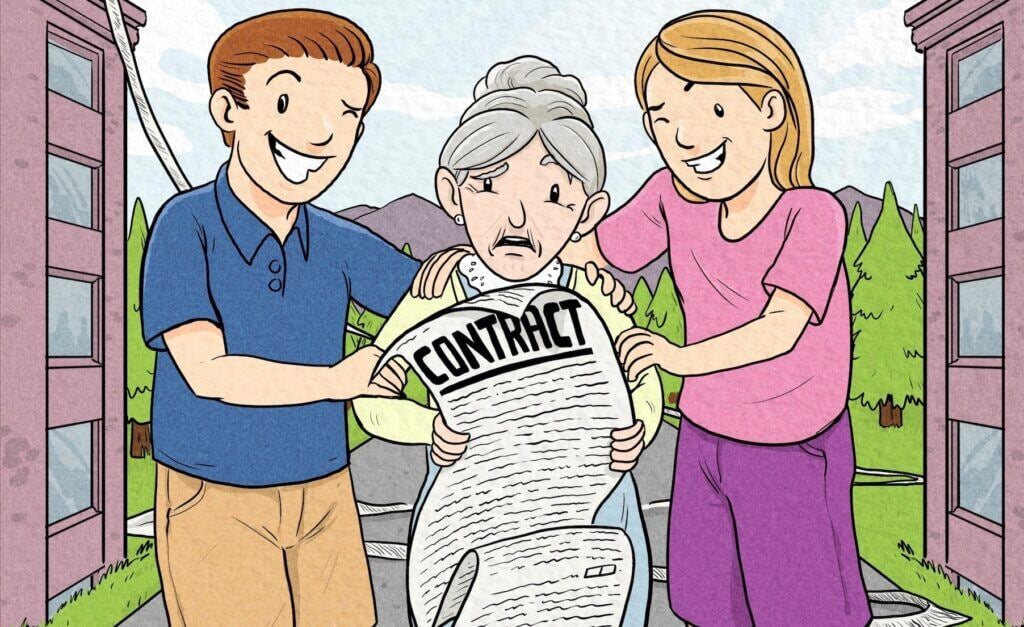

But Church and State are far from the only authoritarians seeing value in indoctrinating guileless kids. I learned this recently when the unscrupulous editor of a popular leftist magazine, let’s call it Present Developments, mailed me a large box of libertarian children’s lit known as the Tuttle Twins series, a series of illustrated stories and workbooks designed to teach youngsters the wonders of the free market. (You may have seen ads for it on Facebook.) Having now perused all 11 books in the special “Tuttle Twins combo pack,” I can confirm that it’s exactly as bad as you think it is.

From the Mouths of Babes

Each Tuttle Twins book is based on the lessons of a prominent intellectual from the libertarian right, like Friedrich von Hayek, Ayn Rand, or Ludwig von Mises, with a dedication to the figure and a small bio on their work at the end. The author is Connor Boyack, Utah resident, Brigham Young U grad, and president/founder of Libertas Institute, a free market think tank, which is great considering we only have about nine hundred of those. He claims, “In that capacity he has changed a significant number of laws in favor of personal freedom and free markets,” presumably when not writing abominable Ayn Rand propaganda for defenseless kids.

The first book in the series, The Tuttle Twins Learn About the Law, is based on the work of Frederic Bastiat. The twins themselves are a pair of earnest, curious kids, whose teacher assigns them to “ask a wise person to teach them about something very important,” which as an educator I can tell you is a great pedagogical technique. They go to their neighbor Fred, who takes them to his home library, with an incongruously lovingly rendered bookshelf with many recognizable libertarian titles, from Murray Rothbard to Ron Paul’s End the Fed to, somehow, Jeremy Scahill’s Dirty Wars.

Fred gives them Bastiat’s book The Law and summarizes the highlights, starting with “We have rights,” things we’re allowed to do “and nobody else is allowed to stop me.” “Like playing with my own toys?” asks a twin in incredibly natural dialogue. You can probably see where that’s going—in the minds of libertarians “my own toys” becomes large-scale property, like palm oil plantations and plastics factories. (POP QUIZ: What’s the difference between the relationship of a child to their toys and the relationship of a capitalist to a giant factory? ANSWER: big productive property confers economic power on its owners, to hire and fire people, and to shape market outcomes. If your toys were sentient beings and you could give them orders, your claim that nobody could tell you what to do with them would seem much less compelling!)

But the twins soon learn that their rights can be violated by “bad guys,” and some of these “bad guys” can be in government, doing things “a lot of people like” but that are bad. Stepping into his tomato garden, Fred observes that it would be wrong for a neighbor to take his tomatoes without asking, and then says it’s just as wrong for the government to take them and give them to the neighbor against Fred’s will, which is illustrated with a masked cop stealing a bag of produce for the poor, providing a valuable window into the feverish libertarian imagination. “Stealing is always wrong,” the kids write in their notebook, letting someone’s raised produce beds stand in for the tens of billions of dollars Mike Bloomberg hoards for vanity presidential campaigns while kids drink lead-tainted water in school and do KickStarters for their insulin. (The way libertarians make their reasoning persuasive is to always use examples that are completely different in scale; so “Would it be wrong for the government to tell you how to run your lemonade stand?” is treated as identical to “Would it be wrong for the government to tell you how to run your giant sulfur mine?” “Property” is used generically to describe both apples and factories, with the buried assumption that there are no relevant qualitative differences between these two types of things that affect the legitimacy of the state regulating them.)

Of course, the right has to recognize that to its regret, a social safety net is widely popular. People don’t wish to live in a society where the weak are left to die. So, as usual, personal charity is invoked as an effective substitute for government aid. We learn that Fred will “make meals for families when the dad loses his job.” How nice! But sadly “the government forces me to help people, too,” as in paying cruel taxes for Social Security and food stamps. Who knows why we’re made to do that! Maybe because the average length of unemployment in the US in January 2020 was 22 weeks, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which comes out to 462 missed meals per person, or 2,772 meals for the depicted family of six. Better get cooking, Fred! Or just pay your fucking taxes.

The kids learn this evil tax-funded social safety net is called “legal plunder,” and having read their Bastiat well, they give a jar of tomatoes to a neighbor (who is lightly implied to be poor), declaring “We wanted to share with you, and nobody else made us do it.” Take that, stupid Children’s Health Insurance Program!

Over the course of the many, many, many books in the series, the twins learn other lessons steeped in the hoary right-wing fever dream of the oppressed wealthy. In The Tuttle Twins and the Miraculous Pencil, the kids learn the staple economist story that “no one person knows how to make a pencil,” because all of its components are made in different places around the world, each with their own processes, workers, and inputs. The market efficiently organizes such activity through price signals driven by supply and demand. Much of this market worship is explained to the children by their elementary school teacher, Mrs. Miner, who is rendered as a Black woman. This is somewhat problematic, as women and people of color are famously underrepresented among the far right in general and the libertarian tendency in particular, and in fact African Americans are broadly more socialist than the wider US population. Something about the white, white Utah author’s having his far-right words come from the mouth of a working class woman of color is, shall we say, distasteful. (Or, shall we say repugnant valor-stealing turd polishing? I leave the reader Free to Choose!)

In The Tuttle Twins and the Road to Surfdom, dedicated to little-known selfless philanthropist Charles Koch, the Tuttle family is dismayed to find the road to their beach house is highly congested, and the stores nearby are closing down. “Ethan and Emily like playing at the beach, but they loved shopping at La Playa Lane.” The displeased vacationing white family soon learns that “a few years ago, voters approved a Master Transportation Plan,” which in addition to building a new road to another beach town nearby, bizarrely closed off the existing road. This is the kind of contrived parody of public planning that market fundamentalists imagine is to blame for capitalism’s problems.

The kids go to work with their uncle, an alleged journalist, and interviews soon show the Big Government Road has caused unintended consequences, from lowering home values on the old road to raising traffic near the new one, and the state used eminent domain to build the highway through a family dairy farm. Businesses closing on the family’s favorite beach can’t afford to move to the other beach town, Surfdom (ROFL), and the rents there are very high for businesses that can. This is blamed on central planning, when “a few people make decisions for everybody,” even though the story indicates there was a public vote.

This focus on unintended consequences caused by evil government central planning is much-favored on the right, but as I’ve covered before for this fine magazine, it oddly never features unpleasant side-effects from major decisions by centrally-planned commercial corporations. The monumental planning and logistical systems of Amazon, Wal-Mart, and Exxon-Mobil are always left off the hook. These sprawling corporate empires require very time-sensitive movements of literally millions of different products and inputs for making them, shipped around the world in intricate webs, and the companies’ incredible growth is a great, ongoing testament to the potential of central planning. But these commercial planning systems don’t arise in the books, and planning is only represented by contrived instances of government bungling. Weird! To be safe, the book also depicts “Individualism” with a rendering of two people shaking hands, and “Collectivism” as two hands shackled together, in case the dumb kids are just looking at the pictures.

Suffer the Children

Further adventures take the twins to the circus, where they become guest clowns and are soon caught up looking for the star attraction, a strongman predictably named Atlas, who has quit (shrugged). The tyrannical ringmaster had cut the strongman’s pay, and thinks the circus can carry on without him. Soon the kids discover being a clown “was actually pretty easy,” while Atlas labored hard working out, and indeed the entire circus also relies on him to build the tents, hang the tightropes and feed the animals—this apparently being a carnival without carnies.

The slothful clowns resent Atlas’s popularity and workplace perks, and spout evil egalitarian lies like “We all make this circus work together” and “We’re all just as important”—typical Marxist frauds of course. In time the kids learn “these clowns need to understand that some skills are more valuable than others…Atlas has talent that is harder to replace—and that’s why he’s more valuable.” The Russian organist pipes up and “remembers history,” saying the clowns’ seductive demands for equality “destroyed my Russia,” previously a lovely problemless place.

In the end the kids talk Atlas into returning to the circus, and he dramatically saves everyone when the pole supporting the Big Top starts to collapse, since it was installed poorly without the superman upon whom everything apparently depends. The ringmaster takes Atlas back and Everyone Learns Their Lesson.

Except author Boyack, apparently, because in his desire to insert adult libertarian literary references into his god-awful kids’ books he has rather badly mangled Rand’s point. Rand’s hit Atlas Shrugged depicts a world where CEOs are not just senior managers like usual, but also the engineers who design their headquarters and the scientists who develop new products. They are also depicted as highly attractive and have cool edgy sex. But when intrusive government regulators, who are not sexy but fat and gross, begin meddling, the elite capitalist innovators desert the world for “Galt’s Gulch,” and the world falls into destructive chaos without them.

But here Boyack has depicted the character Atlas as the cartoonishly indispensable figure, and in his eagerness to justify the cutesy use of the iconic name has made him into a worker at the circus, who quits after his pay is cut by the tyrannical ringmaster. While the book is as jammed as the others with pro-market economic vocabulary and stale right-wing life lessons, it seems to accidentally depict the leftist response to Rand’s capitalist supermen—it’s the workers who actually produce the goods and services we rely upon. The joyless Rand must be spinning in her grave, one hopes. The lesson of the book is properly understood as: capital depends upon labor, and if labor is withheld through a strike, the capitalist enterprise collapses. Let’s hope kids are smart enough to sniff out the socialism. (Although the circus setting is a bit poorly chosen, because if there is one place where a single individual’s act isn’t missed especially much, it’s the circus—if the Strongman performance is replaced with another trick by the lions, or two more minutes of clowns, who cares? If Atlas shrugged, would anybody notice?)

Similar blunders appear in The Tuttle Twins and the Messed Up Market, dedicated to arch-conservative Austrian School founder Ludwig von Mises, who so hated social democracy he wrote:

“It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aiming at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has, for the moment, saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history.”

(The quote does not appear in The Tuttle Twins and the Messed Up Market, surprisingly.)

In this fun episode, the kids come into three grand each when the family sells its theater business. The Twins decide to become creditors, extending microloans to other kids’ businesses. I’m sure we all had the same childhood experience.

Soon the kids have made a loan, although one that sadly betrays their banking amateurism, since it’s to a hardworking kid of color. (“Redlining” does not appear in the Glossary of Terms, although useful terms like Praxeology do make the cut.) Soon the twins have organized a Children’s Entrepreneur Market, held on a church’s grounds so Boyack can avoid issues of market access, which in reality is often controlled by platforms like Amazon or monopolists like the cell phone app stores. (Again, the entire reason libertarian logic is persuasive is because its examples all take place in a world of children’s lemonade stands, rather than in an actual adult marketplace were giant corporations dominate markets and have the power to crush new entrants immediately.)

The kids learn about incentives, opportunity cost and other Econ 101 basics, much of it from Mrs. Dobson, another of the women of color whom Boyack apparently enjoys using as mouthpieces for his overwhelmingly white boy school of thought. They speak approvingly with a young girl selling candied apples, who’s working hard because “I really want to earn money to help pay for my dad’s medicine. He’s sick and it costs a lot of money, so I want to help.” “That’s a really good incentive,” replies Mrs. Dobson.

But the market gets Messed Up when a kid undercuts everyone else’s sales with 25-cent brownies, a price point he can afford because his parents are paying him to be there—a “subsidy” as we say in the evil sciences. This attracts customers from the candy apple kid thanks to “unfair competition,” even though it’s happening because the kid is getting money from his parents, with Boyack apparently not realizing that the unfairness of spoiled kids getting inherited fortunes while everyone else struggles is another socialist argument. In fact, the story is a perfect example of a “free market” in operation; the other kids parents weren’t the government, they were private actors with a private fortune, and what we have actually seen is the tendency for concentrated private wealth to destroy the possibility of market competition.

The story then follows the reactionary canard of blaming all of capitalism’s numerous faults on government subsidies, e.g. a family had to close its arts studio business because the dirty city government put up a Community Recreational Center, which was subsidized and drew the business away. Of course, public goods like rec centers are mostly important for less wealthy people who aren’t getting money from their family—which the book just pretended to be against, because actually Boyack has absolutely no problem with independently wealthy people unfairly competing against those with less wealth.

But the poor market is dealt a deathblow when police arrive with the city manager, who—I shit you not—says: “Folks…children…I understand that you’re all just peacefully buying and selling things, but…” Horribly, the all-powerful authoritarian state requires business permits, and apparently every parent in town is so blunderingly inept they didn’t think of this while their kids were supposedly setting up a giant Kid Biz Fair. So, the manager declares “This market ends now.” In a moving, National Book Award-deserving passage, “The sound of small, chilly raindrops pattered through the market as police officers hovered over the families packing up their booths.” What a bunch of goose shit. Oh, and business licenses in Utah cost about $20-$50. (And the reason the state needs to charge people to do business is that the state the entity that bears the costs of enforcing property rights and creating the infrastructure for any commerce to take place at all.)

The Tuttle Twins books have reasonably appealing watercolor illustrations, and the typical low-watt visual gags of a bored illustrator—three kids at the market are drawn to resemble Alvin and the Chipmunks, Atlas has the logo of Rand’s Shrugged on his workout shirt, and there’s the meticulous rendering of the reactionary bookshelf at Neighbor Fred’s. The artist also produced campaign videos for Ron Paul’s 2012 presidential candidacy, in case you were thinking of letting him off the hook.

Free-to-Choose Your Own Adventure

Finally, there are the choose-your-story format books. These are similar to ones you may have read as a young person, written for teenage readers with fewer illustrations and clearly meant for the sprawling YA market. Adorably, the books aren’t “choose your own adventure” like the popular commercial books but “choose your own consequence,” because the Gummint and its Unintended Consequences.

In The Tuttle Twins and the Case of the Broken Window, the kids are in a high-stakes, end of season baseball game, with a tying run on base, apparently in the Cliché League. But Emily’s great at-bat destroys a priceless window in the local church, and we must choose: Run Away or Come Clean. Let’s be responsible socialists and Come Clean.

The church is insured, but once again Boyack thoughtlessly reminds us of capitalism’s shittiness when Father McGillivray observes the policy has a $5000 deductible, “and our rates will go up. We would prefer not to make a claim at all.” You might think that if it’s too expensive to use, what the fuck is the point of the insurance market at all, but that’s not the Tuttle Way. The kids’ family agrees to pay the deductible and have the kids work it off, which they do by having them intern for their Uncle Ben, who’s “got this YouTube news broadcast that’s pretty popular,” quite the pickup line.

Soon the kids are at their uncle’s rented offices in a poor part of town, and we learn the city’s planning to build a sports stadium—four of them, in fact. Folks, you may not believe this, but what’s the kids’ reaction to this incredibly plausible-sounding city plan? “‘And how are they going to pay for them?” Emily said. ‘Bingo,’ said Uncle Ben.” I probably should have included a content warning that your mind might be blown away by these market truths.

We learn the city is apparently planning to use eminent domain to demolish a poor neighborhood to build the stadiums, although the book treats this it like it’s a big mystery, when this kind of corporate-driven development plan is usually taken up in city council meetings, along with the bond issuances to Pay For It. But checking in with reality is not one of the available Consequences, which instead are Go to the Archives or Go to the Neighborhood. I’m hoping for some more natural-sounding dialogue, so let’s Go to the Neighborhood.

Boy, do I get it. “I don’t think this is the part of town you want to be alone in,” Ethan says. They encounter a girl on a stoop who we’re told has braided hair, who introduces herself as Shiana Douglass. She says “This is our house but the city men come and say we hafta move but we don’t wanna go because Mam says we like it here better than anyplace we been before.” The boy adds “we ain’t goin’” before their mother, “A large woman with a halo of hair sauntered out form inside” as “The two children peered around her backside, their white teeth flashing.”

Now folks, Boyack does not specifically say these people are African-American, and only later in some of the branching choose-your-storylines do you see illustrations confirming this, but you may have inferred it from the incredibly artful rendering of urban speech. The use of Douglass, and presumably the reference to the escaped slave and great public intellectual Frederick Douglass, is especially pitiful, since Douglass wrote: “Experience demonstrates that there may be a slavery of wages only a little less galling and crushing in its effects than chattel slavery, and this this slavery of wages must go down with the other…it is hard for labor…to cope with the tremendous power of capital in any contest for higher wages or improved condition.” Not exactly the Fountainhead!

And once again, we have Boyack speaking through women of color. Mrs. Douglass elaborates that “You need to understand, because my guess is you don’t come form this part of town, that the economics don’t support this ballpark idea at all.” The children explore the neighborhood, approaching a basketball court where “Rap blared,” when “A huge young man, glistening with sweat, stepped in front of them. He held the ball in a pair of meaty hands, dusty, as if covered with powdered sugar.” The young man, Carter, explains that the community resents white efforts to improve conditions, which only lead to urban renewal and demolition of black communities. Of course, African-American voters are heavily in favor of funding actual social democratic programs of social uplift, with 74% supporting Medicare for All and 76% favoring free college tuition. Boyack’s continuous clumsy use of black mouthpieces is pretty bizarre. Unrelatedly, did you know Utah is only 1.4% black?

The kids reflect on their privilege and how they can help the poor community develop economically, mostly by developing “trust.” Sadly, this storyline leads to the kids failing to stop the demolitions, but the story consequences vary widely, including the kids exposing unsustainable city budgeting, getting mixed up in a window-smashing and repair racket, stopping the redevelopment itself, or going to jail for their terrible crimes against windows. And yes, I looked through all the endings and none of them have illustrations of guillotines. Perhaps I can choose an adventure where I never become an economist, never meet Nathan Robinson, and thus never have to read these godforsaken joyless cow flops!

There are many more books in the series, I would estimate about nine hundred thousand more, but I will conclude this review by saying the Tuttle Twins series is among the most wretchedly contrived, grotesquely unethically indoctrinating, cliché-ridden heaps of steaming garbage I’ve ever had the misfortune to read. Written to bring young people into one of the most disgraceful political tendencies in the world before they have the critical thinking skills to recognize it, it is a hideous fraud and an ugly twisted farce.