Michigan’s Left

A few months back, my home state of Michigan was dragged under the country’s dizzying and bizarre circus lights, with all of a circus’ terrors and none of its thrills. Conservative protesters stormed the Capitol, some of them armed for what looked to be a strangely intense video game, demanding that we “reopen” as a deadly virus was still hulk-smashing its way through largely poor Black communities like mine. Most establishment figures saw the anti-lockdown protests as dangerously divisive at a time when, as Governor Whitmer stressed, “we are in this together.” But many on the left knew we didn’t have the luxury of rolling our eyes as examples of right wing outrage—some small and exaggerated, others worryingly large with the potential for Tea Party-style astroturf mobilization—continued to mount. As Ben Burgis correctly argues in Jacobin, if the left isn’t “prepared to fight for bold measures…much more sinister forces will flourish.”

Michigan has taken on strange symbolic power in recent years. Since shattering elite forecasts by breaking for Trump in 2016—the first time a Republican won here since 1988—my home state has periodically been shoved under the world’s sloppiest spotlight. And, I gotta say, the show stinks. For the better part of four years, the mainstream media has been wandering around Michigan’s suburbs and former industrial centers, dazed and confused, painting a portrait of an uncertain land torn apart by “suburban trench warfare.” Many moons and much ink have been wasted on an unbearable quest to unlock the supposed mysteries at the heart of the “Midwest sensibility.” It’s all poorly thought-out of course, and shows no interest in the Black and brown Midwesterners who have every reason to reject both parties as deeply unserious about addressing their material suffering. But this kind of reporting fits the pre-approved conclusions about plaid-covered midwesterns torn between their hatreds and their self-interests (as if hatreds aren’t an interest people fight to preserve).

Nationwide, unemployment is “literally off the charts,” with tens of millions filing for benefits as the country gallops toward a second Great Depression. Food insecurity is spiraling upward. Millions are needlessly losing medical coverage, exposing the obvious and cruel stupidity of attaching healthcare to private employment. While the Center for Disease Control’s new eviction moratorium will help to protect some tenants who are unable to pay rent, it won’t help tenants whose landlords cite other reasons for eviction, or who are thrown out in informal evictions that never see a courtroom. Housing advocates are predicting a “tsunami of evictions” if we don’t move swiftly, as Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor argues, to “cancel the rent.”

None of this is the natural result of economic collapse. Mass suffering is a choice, made every day by the people who rule the country and could do different things. We know because other countries exist and some of these different things are done in them. Instead of adopting “disastrous programs” where “money is not going” to the working-class communities “where it’s needed most,” as economist Joseph Stiglitz told Foreign Policy back in April, we could have “directly reimbursed businesses for maintaining their workforce during the shutdown, as was done in Europe.” As Vice reports, we also could have avoided the “uniquely American” “issue of healthcare” in which “people who lose their jobs are also losing their insurance” by adopting a Medicare for All style system present in other countries where no one has to ask themselves “‘Can I go to the doctor or not?’”

But because establishment media and political discourse is so polluted with garbled nonsense about what can and can’t be done, the choir of progressive voices must continue to rise and tell better stories about the “portal” this pandemic provides for remaking the world. The Michigan section of that choir is growing. Take groups like MI Covid Community, of which I am a member. Formed in the shadow of COVID-19, we’ve brought more than 100 grassroots organizations together under this single banner to connect people to mutual aid while also joining forces to make concrete demands on our political institutions. As my comrades Art Reyes and Betsy Coffia spelled out, at the exact moment the media was “fixed on the threatening actions” of a cartoonishly armed few, “another gathering [of thousands of] Michiganders was taking place” just as our Stay Home order was set to expire.

“Rather than fanning the flames of fear and division” write Reyes and Coffia, our democratically-run crew gathered online to share “stories, art and music, mutual aid resources” and demand that “policies provide real relief and keep all our communities safe.” Spanning eight hours on April 30, and marking the climax of a seven-day week of action, many of the ingredients of a basic egalitarian agenda were there, including an absolute right to things like healthcare, housing, water, and education “regardless of citizenship status or ability to pay,” and, of course, a habitable planet to enjoy them all. Thousands of people tuned in to hang out in our virtual auditorium of passionate and very cool leftists, with special cameos from progressive faves like Naomi Klein, Dr. Abdul El-Sayed, and Kerry Washington. Our goal was simple: to paint a picture of the world as it could be, and provide people a toolkit for hammering those demands into their elected officials. By the end of it all, our call to action led to thousands of petition signatures, emails, and tweets being sent to local officials, a stadium’s worth of bulletins highlighting our demands in bright and unmistakable colors.

These are all longstanding demands of the left anyhow. And our choir—of economic, immigrant, environmental, and racial justice organizations, to highlight just a few—come from communities across the state where they’ve spent years doing the thankless, grinding work of fighting for a better world. Thanks at least in part to public pressure and encouragement, Governor Whitmer has repeatedly extended the state of emergency. Meanwhile, our groups have continued to organize together in neighborhoods and communities across the state to fill the gaps in human need that wouldn’t exist in saner nations, while still pushing the state’s decision-makers to extend and deepen the meager relief provided up to this point. Our next challenge, and current subject of deliberation, will be to bring a little imagination to Michigan’s budget battle, because of course our state’s ghoulish Republican Senate Majority Leader is telling people on the brink of starvation and eviction that we must “suffer through” these hard times.

Luckily, the left has some ideas about strengthening the common good. We could, for instance, do reasonable things like snatch healthcare and housing and other basics out of the luxury goods aisle and place them in the public commons as one of the things you get for being a human. And while we haven’t won each and every one of our deepest egalitarian aspirations, alliances of everyday people in Michigan have flexed real muscle and won real victories by guarding against further abuse from the elite, and showing us all what a future governed by the priorities of everyday people might entail.

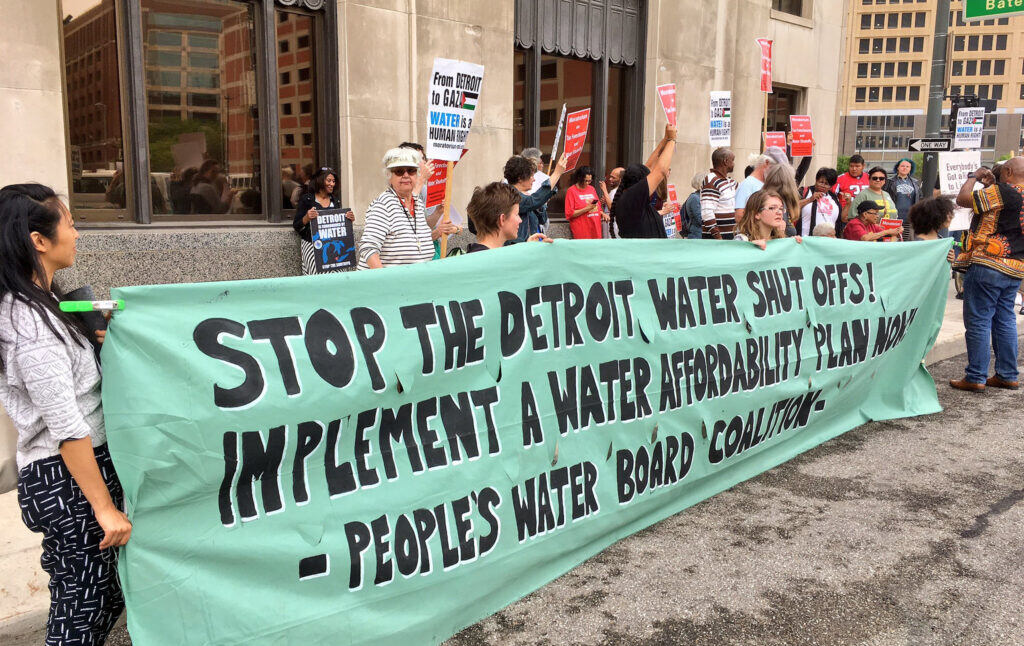

Take water. Over the last several years, Detroit has carried out more than 140,000 water shutoffs in spite of UN declarations that this constitutes “a violation of the most basic human rights” as well as widespread outcry that blocking the flow of water to poor families is unconscionable bullshit. As the pandemic sunk its teeth into Detroit, our “water warriors” successfully pushed the governor to halt and reverse shutoffs. Recently extended through the year, organizers and activists have dug their heels in for a fight to make the changes permanent. Monica Lewis-Patrick of We the People of Detroit put it potently when she urged popular movements to “make sure that every policy recommendation…becomes life. That it grows legs.”

“Those legs and arms,” she thundered, “are your legs and your arms…We’re not going to let this moment of harm and death and destruction define us.” Instead, “we’re gonna make it a catalytic moment that takes us from trauma to transformation.” Besides its role in extending the moratorium on water shutoffs, We the People of Detroit continues to fight for a basic water affordability plan and a public water utility that serves the needs of everyone instead of demanding ransom payments for basic necessities.

Because what kind of sociopathic society makes luxury items out of basic necessities? Early on in Michigan, as in many other corners of the country, a web of tenants’ rights groups rose to demand that no one be forced from their home because they’ve lost their job to the plague. Their first victory was a modest eviction moratorium. But they didn’t stop there. Organizers kept the fires of outrage burning, circulating petitions and staging car caravan protests until the governor extended the ban again and again. Though the state’s moratorium lapsed in July, and the city of Detroit’s expired August 15, activists I’ve spoken with are nowhere near relenting. Just the opposite: they are now carefully deliberating how to make the pandemic-related eviction bans permanent by cancelling rent altogether. In the meantime, organizations like Detroit Eviction Defense have experience blocking the path of dumpster trucks that get menacingly left outside of people’s homes before court-appointed goons arrive to throw people onto the street. Organizers I spoke with have looked to cities like New Orleans for inspiration, where dedicated, ordinary people jammed up eviction courts the day the city tried to restart them. Elsewhere, known Midwestern icons with Kansas City (KC) Tenants have been really flexing lately, disrupting eviction court proceedings and exposing cruel slumlord fraudsters. They also won a Tenants Bill of Rights late last year, which, among other things, “affirms tenants’ right to organize,” a critical protection as experts warn “an eviction crisis of biblical proportions” is about to rain down on our heads.

Detroit organizers are getting in on this. Thanks to a network of racial, environmental, immigrant, and disability justice advocates, a Detroiters’ Bill of Rights is making its way through the local arteries of power. If adopted by the city’s Charter Commission, the progressive policy package could strike an important blow against the city’s towering racial and economic inequality. Its demands are clear and bold, establishing an absolute right to things like food, water, housing, recreation, and transportation. It’s a powerful reminder of what’s possible as elected leaders everywhere shake their heads in anguish and pretend to be powerless in the face of disasters they absolutely have the power to address.

Michigan’s left is also making electoral noise. As The Intercept documents, our August primaries saw a strong chain of progressive wins. For the state legislature, Abraham Aiyash, a Sanders campaign surrogate, won the 4th district primary in Detroit to replace another Sanders veteran, former State Rep. Isaac Robinson, who died tragically of COVID-19. Over in another section of the city, the 7th district, former Jobs With Justice organizer Helena Scott also prevailed. And adding to the growing nationwide march of progressive prosecutors, reformers Karen MacDonald and Eli Savit won closely watched races against more establishment figures, while Victoria Burton-Harris ran a thoughtful and staunchly progressive campaign against longtime Wayne County prosecutor Kym Worthy, despite falling short. And lastly, and so very satisfyingly, Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib convincingly thumped her establishment-backed challenger, erasing any doubt that the Left has some staying power in a state that has so puzzled centrist observers. These are important victories. Not because they mean the revolution is finally nearing the gates, but because it reflects the left’s increasing potency in the land that birthed Reagan Democrats.

One of those prosecutorial races, in fact, was only the second most important showcase of progressive power in the region it took place in. Oakland County is one of Detroit’s wealthy suburbs. Karen McDonald won the primary there by running on increasingly mainstream leftist ideas like ending cash bail and no longer prosecuting marijuana possession.

When ProPublica broke the story of Grace, a 15-year-old student who was imprisoned for not doing her homework, one of the most forceful voices was Michigan Liberation, a group dedicated to building “a long-term movement” to transform the criminal punishment system. After they organized the first rally, communications director Marjon Parnham tells me, it was “just like a domino effect.” More rallies followed calling for Grace’s release, as more and more people were stirred with “the courage” to “do something.” In one especially courageous and kickass show of solidarity, Black Lives Matter in All Capacities, a group established by Black teenage girls that stepped into a prominent leadership role and “organized an overnight occupation outside of Oakland County Children’s Center,” where Grace was being held. For Parnham, it was a testament to the power of grassroots action. “If we would’ve had to wait for this person running” based on “what they may or may not do…oh, my goodness, can you imagine? We would be waiting forever.” It was the perfect split-screen lesson: on one, a progressive challenger is elevated by grassroots leaders to dislodge a status quo incumbent. On the other, that same grassroots movement demonstrates that they will be there every step of the way, prepared to move swiftly and aggressively if that challenger should fail to follow through. After nearly three months—and relentless public outcries of “how fucking dare you?”—Grace was released.

Grace’s story is just one infuriating window into a much wider reality. Michigan ranks near the top for coronavirus deaths behind bars. As Ricardo Hart, who’s incarcerated in Michigan, put it in a recent report, “There is no such thing as social distancing in Michigan prisons, only the death penalty.” Titled “I Don’t Want to Die in Prison,” the report pulls together firsthand testimony from hundreds of incarcerated Michiganders, and rightly concludes that the only appropriate response is rapid and dramatic decarceration, and the eventual abolition of a system that cages human beings.

We must be clear about this: both the virus and capitalism have the vast majority of us on a death march. And, as Arundhati Roy writes, “the pandemic” can be “a portal,” and we can decide to emerge from it and live differently. Imagine all the pie-in-the-sky we could have if our national priorities looked more like the demands of working-class communities across the country. Wherever possible, the left should be marching in to fill the void. The “how” of this isn’t a mystery. Jane McAlevey puts it plainly when she states that “only the slow and steady work of smart organizing” can save us. That means expanding our base by kindling and igniting the imaginations of everyday people in workplaces and neighborhoods everywhere we can, building unity and solidarity that can withstand the backlash of the super-wealthy and powerful. If we don’t, as Burgis notes, the most vile narratives will take root and blossom.

This is what nearly happened when the phony populist protests came to Michigan. A deadly pandemic is on the rise, the economy is totally sunk, and people are left to doggy-paddle through oceans of uncertainty. In that context, it makes perfect sense that some would object to only being given janky life rafts to float around on. Whatever the motives of the protesters, many people who are genuinely concerned about their material lives are looking for explanations. The right will enthusiastically provide them. It was the Michigan-based DeVos family (as in Trump’s public school-hating Education Secretary, Betsy DeVos) who funded institutions that helped bring those protests to life, representing a real core of diabolical economic power in the state that couldn’t care a lick about what happens to working people.

To be clear then: the real issue here isn’t that this pandemic, and its many avoidable horrors, has opened up new and hotly contested theatres of conflict. It’s the way the battle lines have been drawn and which side of it people find themselves on. In Michigan, we’ve been making the argument that, as another comrade Maria Ibarra-Frayre writes, “More is possible when we work together.” Not only to get people the things they immediately need, but to fight against the enormous forces of private power and their pals in public office who have made life so desperate for so many.

It’s important that we give them hell. As lefties often stress, the country’s ruling class has been warring against working-class people since this bloody story began. Take founding father John Jay, who reportedly loved saying, while no doubt thinking he was hot shit, “Those who own the country ought to govern it.” He meant it, and so do his ideological heirs.

As any hope that we can “return to normal” without simultaneously triggering enormous human suffering continues to fade far far away, the left desperately needs a persuasive answer for how we can secure people’s well-being without throwing them in front of the plague. In order to do that, we can’t pretend that those in executive suites and private villas have basically the same interests as those surviving off of food pantry rations or who ride the bus to work every day terrified that they won’t make it out alive. The ruins of market capitalism, and the horrific human costs of tying public fate to its whims and incentives, are all around us. And it has again made clear that our best shot at a sensible, humane world lies with everyday people demanding a full menu of social democratic policy.

This is why the Michigan example is important for the Left. As organizers here know too well, ours is one of the most viciously segregated states in the country. And with plenty of economic despair to go around, the ground is fertile for classic divide-and-conquer politics that drives deep wedges between communities that should be building lasting solidarity. After all, the multi-racial working class is rich with shared adversaries, but also with shared aspirations. The latter has become increasingly clear thanks to the tireless dedication of everyday organizers here, proving that people in the rustiest of states still have lively and kinetic imaginations, and that we can “go into difficult terrain” and raise “people’s expectations that their life can be better.” If only, as Reyes and Coffia write, we reject the “shadowy billionaires who seek to stoke fear and paranoia” and instead decide “to have each others’ backs.”