Magic and Capitalism

Katie Jane Fernelius on the meme of magic, the sincerity of its deceit, and what we’re too eager to believe.

In 2015, the CW premiered a new reality competition show filmed in front of a live audience at the Rio Hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada. It was a familiar format: each episode chronicled performers eager to show off their talent in front of a panel of judges.

Typically, the talent-show-as-TV genre asks the judges to assess whether the contestant has “got it”: the charisma, the voice, the capability of being developed into a commodity. But Penn & Teller: Fool Us is different. The conceit of the show is simple. Prestidigitators, illusionists, mentalists, and magicians perform a trick on stage. Then, judges Penn Jillette and Teller attempt to figure out how that trick was done. Using vague language and verbal sleight-of-hand, they offer up their theory to the audience. More often than not, their theory is correct. (Behind the scenes, several magicians verify the tricks’ procedural elements, independent of the judges.) But if Penn and Teller are wrong, then the magician wins a trophy, and an opportunity to open for them in Vegas. Most of us in the audience, both in the theater and at home, are none the wiser about the trick’s mechanics despite Penn and Teller’s evasive explanations. As witnesses, we are there to be fooled.

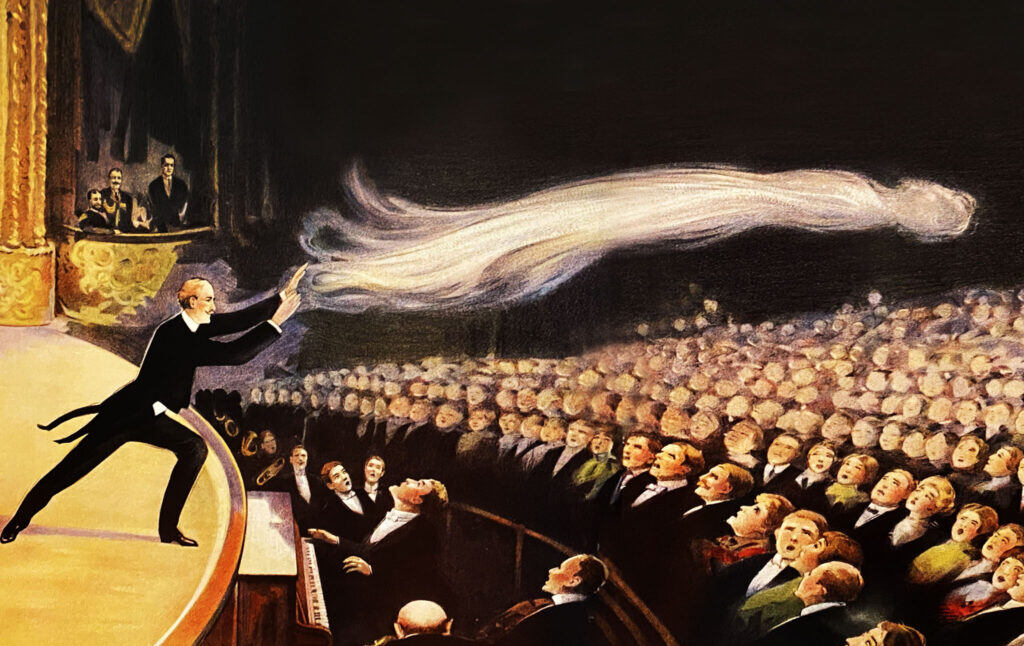

This is part of what makes stage magic such a strange art. It rests on a tacit agreement to be fooled, to be lied to. We enjoy the show with a wink, having consented to the pretense and well aware of our role in the game.

To be a magician is to play a character. My sense is that magicians are not attempting to swindle anyone out of their money, and few if any nurture a genuine belief in the occult. But they may enjoy the playful make-believe of doing so.

While magic is often confined to specific contexts—children’s birthday parties, dinner theaters, and hotel casinos—it was a pastime in my house, practiced like a cello and solved like a Rubik’s cube. My dad is a magician. He can make coins spill out of my ear, produce felt balls under copper cups, teleport a card from the middle of the deck to the top, and tear safety pins through a handkerchief without leaving holes.

To grow up in a magic home was to grow up in a church of the peculiar. Our bookshelves were bloated with what felt like hundreds of books on magic. Magician-writers like Eugene Burger, Juan Tamariz, and Roberto Giobbi were as canonical to us as Dickens and Proust and Shakespeare. We ordered Bicycle playing cards in bulk so my dad could always carry a fresh deck in his pocket. For a while, his vanity license plate even read “LEGERD ????,” a play on legerdemain, from the French for sleight of hand.

When I tell friends that my dad is a magician, they usually make jokes about G.O.B., the goofy character from the sitcom Arrested Development. An enthusiastic practitioner of magic, G.O.B. insists that what he does are illusions, not tricks, although he is atrocious at both. Eventually, he founds the Alliance of Magicians and adopts the slogan, “We Demand To Be Taken Seriously.”

Although my dad isn’t pitiful like G.O.B., he does take magic seriously. A devoted student of Jeff McBride’s Mystery School, he completed workshops on escaping straitjackets and has developed philosophies of magic. Before the pandemic, my dad spent most weekends hanging out with other magicians at the Magic Castle in Los Angeles. He is also a member of the International Brotherhood of Magicians, whose name and emblem evoke the aesthetic of 20th century trade unions, which gives it a certain gravitas.

I realize that taking stage magic seriously can feel silly. It can be misinterpreted as saying “magic is real,” as if the illusions and tricks are real ones, and really happening.

Nor does it help that the term is used so expansively. When it’s not gaudy entertainment, magic can be a marketing ploy, an anthropological designation, a practice of the occult, or an accusation of political dissidence.

These various usages evidence the difficulty of extricating our understanding of magic from religion and social life and trade. Popular histories of magic, like the 1998 PBS documentary “Art of Magic,” lump all of these practices under one big umbrella, blurring together their unique histories, influences, and politics.

While it may be tempting to reduce magic to a straight lineage from theater acts of the Italian Renaissance to a stage magician like Lance Burton, magic is best understood as a meme, which is to say a form repeated under diverse conditions and contexts, propagating but always changing.

The entertainment magic that one can expect on Penn & Teller: Fool Us is the close-up sort. Cards, coins, cups and balls. Women sawed in half. Doves appearing and tigers disappearing out of thin air. Endless handkerchiefs, escapes out of straitjackets, and levitation. But the term also signals a broader feeling of enchantment even without the performance of illusion or sleight-of-hand. Think of the magic of Christmastime or of Disney. Highly produced effects designed to delight, as much as it is to bewitch us into spending money.

Other rituals from around the world, like dancing for rain or séances with the dead, might trigger similar feelings of enchantment. Calling such practices magic typically carries a different implication. It suggests a literalness to the enchantment and can delegitimize these practices as mere superstition, implying an inferiority to cold, hard Western facts.

In medieval and early modern Europe, magicians were often associated with barbarians or “the Orient.” (In reality, some of their magical practices emerged from early European pagan religions as much as from outside influence.) Magic was seen as deceptive, opening practicants to charges of heresy and eventual persecution in a Europe dominated by Christianity. During the European wars of religion, an estimated 30,000 alleged witches and magical practitioners were executed. In 1584, Reginald Scott published Discoverie of Witchcraft to demystify the “folly” of what might otherwise be attributed to the devil; magic was merely sleight-of-hand, he claimed. But this did not put an end to persecution, just as explaining the science behind evolution hasn’t yet convinced creationists that the Earth is billions of years old. As historian and priest David Collins puts it, “…the witch trials were born of power plays by religious and secular forces that wanted to gain greater control over religious and civil communities.” Magic was a way for authorities to name a threat and reassert a Christian Europe in contrast to it.

In the late 19th century—anthropology’s earliest days, which were tied up in a knot of post-Enlightenment philosophies, Victorian cultural values, empire, and colonial violence—“scholars classified magic, religion, and science in different categories, corresponding to progressive ‘stages’ of cultural complexity, with magic attached to ideas of archaism and childlike irrationality,” explains social anthropologist Matteo Benussi. 19th century anthropologists documented “newly discovered” communities in Africa, South America, and the Pacific Islands as living artifacts of the past, arrested in evolutionary development, rather than contemporaneous societies. Magic may not have been seen as a threat by anthropologists in the same way that it was viewed as a threat by earlier religious authorities, but it once again became a category against which to define Western civilization.

Today, a robust and thorough scholarship on the diverse “magical” practices of the Global South understands and recontextualizes such practices in the non-Western world as sophisticated and legitimate traditions, and as profoundly modern ways of navigating cross-cultural relationships within a colonial and capitalist context. What Western institutions mischaracterized as magic was often what it simply deemed illegible and confusing, like endowing inanimate objects with spiritual character.

But of course, such superstition figures into contemporary, hegemonic Western culture, write anthropologists Brian Moeran and Timothy de Waal Malefyt:

The modern world is no less mysterious, more rational, knowable, predictable, and thus ultimately manipulable, than the premodern world. Magic has not declined, to be replaced by science, bureaucracy, law, and power. Rather, modern societies thrive on glamour (an old Scottish word, gramyre, originally meaning ‘magic,’ ‘enchantment,’ or ‘spell’), deception, illusory feats, ritual, symbolism, drama, theatricality, fake news, and tweets.

Moeran and Malefyt seek to correct early anthropologists’ condescending and othering treatment of magic by presenting a litany of examples of magic in capitalism. Many makeup slogans evoke transformation (“Because you’re worth it”, etc). Moeran and Malefyt also compare the World Economic Forum at Davos to an assembly of magi called together to fulfill the ambiguous and weighty mission of “improv[ing] the state of the world.” Magic, they argue, is as much in the structure of capitalism as it is in its effects. After all, what is the stock market if not a collection of projections and superstitions about the future?

Today, it is hard to think of stage and close-up magicians as particularly powerful, or as alien, subversive, or damaging forces in our culture. Magicians perform in packed theaters under multi-million dollar contracts; they win seasons of America’s Got Talent; they rack in ad-money as influencers on Instagram and TikTok. Rather than agitate for criminal trials and stake burnings, self-respecting people now pay good money to go to magic shows and be fooled.

English professor Sianne Ngai names the feelings and judgments we experience when we witness magic tricks today—delight, suspicion, the cognitive “turning of wheels,” and disbelief at our own belief—as “the intersection of ‘calculation and enchantment.’”

Although magic is not Ngai’s object of study, it is threaded throughout her new book Theory of the Gimmick. Ngai defines gimmicks—a broad category that includes cartoon Rube Goldberg machines, the credit system, and ridiculously staged canapés of fine-dining—as an aesthetic category of late capitalism that people tend to view as both working too hard and not enough, because it simultaneously reveals and obfuscates how value is produced in a capitalist world. The gimmick thus reflects “the basic laws of capitalist production and its abstractions as these saturate everyday life.”

A gimmick, Ngai writes, can be “an invitation to playful sociality around an object of suspicion”:

What we seek from magic performances […] is a way to distance ourselves from an illusion while enjoying it simultaneously. A way to make the illusion transparent as an illusion—exposing its process, its technique or its ‘trickwork’—without questioning its effectivity or ability to enchant.

Histories of magic note that rapid discoveries and inventions at the turn of the last century, like electricity, germ theory, radio waves, or the expansion of rail and telegraph lines created a new terrain for reality. “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” the late science-fiction author Arthur C. Clarke famously wrote. Indeed, invisible forces like germs could make us ill. Machines could catch and project sound. Cities could harbor electrical currents to light up a street. In the late 19th and early 20th century, it became possible to move and communicate more rapidly than ever before.

Modern magicians were often early adopters of new technologies in order to produce this kind of enchantment. George Méliès, for instance, was an early innovator in cinema and professed illusionist who created some of film’s earliest special effects like substitution splices. During the height of spiritualism, magician Samuel John Davey staged séances in which ghostwriting would appear on previously blank slates, leading audiences to believe that a spirit had communicated with them. (He’d later explain his trickery in an effort to debunk spiritualism as a movement.) Wolfgang von Kempelen, a Hungarian inventor, devised what he called the Mechanical Turk, an automaton adept at chess. In actuality, the machine was operated by a human hiding inside. These charlatans help explain why magicians are so often lumped in with scam artists and con men. The extent to which there can be “playful sociality,” in the words of Ngai, depends a lot on who the magician is and how they are framing what they are doing.

Take the magic-peddlers at Theranos, for instance. Starting in 2003, Elizabeth Holmes and Sunny Balwani claimed to have concocted a technology that could quickly diagnose a wide array of health conditions from just a prick of blood. The company’s actual method was shrouded in secrecy. As Nick Bilton writes in Vanity Fair, “Holmes largely forbade her employees from communicating with one another about what they were working on—a culture that resulted in a rare form of executive omniscience.” But the truth was that the technology did not work, and the claim that it did was entirely an illusion.

Undeterred by this detail, Holmes nevertheless pitched her magic technology to Walgreens, the nationwide chain of wellness clinics and stores. As Buzzfeed News noted, a government report would later determine that “Holmes told her employees to put Theranos’s equipment in the room where they were collecting blood samples from the executives—but instead of processing the blood on the Theranos machines, employees secretly ran some tests on outside lab equipment.” As with the Mechanical Turk, unseen human labor was hiding within the machine. This sleight-of-hand trick bilked hundreds of millions of dollars from Silicon Valley venture capitalists, who might have not signed up to be fooled, but were eager to believe.

This is instructive when we consider what is both appealing and uncomfortable about magic: we want clear expectations about who is fooling whom. This might explain why a show like Penn & Teller: Fool Us is so satisfying—it is unambiguously sincere in its deceit.

Magic offers us “the realization that things are not always what they seem to be,” writes magician and teacher Eugene Burger. This is true whether it’s compelling sleight-of-hand or the elaborate illusions of a start-up. Understanding magic in this way, as Burger does, teaches us that “The world of experience must be approached with an alertness of mind, and it must be examined carefully and even critically, if we are to avoid being deceived by our neighbors.”

The fact is that we are deceived, constantly—by claims about the stock market and how it works, by the accepted pretense that wealthy and successful people are brilliant and their technology works if all the right people believe it works. We want to believe; we want to wonder. We want the world to be magical, no matter how facts-oriented we may have decided we are. And that’s part of how magic endures: as deception, belief, and ritual; sometimes a craft, other times a curse, and, in 21st century capitalism, a gimmick that makes us buy and accept.

At its core, magic stages social relationships and exposes their power to define what is real and what is not. In its most destructive interpretation, it can justify the dismissal, and sometimes destruction, of whole communities. But in its most constructive form, magic permits us to play with cause and effect, to make-believe that reality could be otherwise. It compels us to ask: how do we fool each other? And how do we allow ourselves to be fooled?