The Rot Of The St. Louis Elite Goes Far Deeper Than The “Gun Couple”

They were just a particularly striking symbol of a city built on grotesque racial and economic inequality.

On a Saturday in early March, an exclusive private all-girls academy in St. Louis, Missouri held its annual daddy-daughter dance. Unknown to guests or the Ritz-Carlton staff, a father-daughter pair broke quarantine to attend after being exposed to COVID-19 for days.

The deadly virus had, up until that point, only existed in the news for the St. Louis region. The elder sister of the girl who attended the dance was the area’s first confirmed COVID-19 case; she had just returned from studying abroad in Italy, at a time when the U.S. media was saturated with apocalyptic images of an Italian healthcare system under enormous strain. Videos of Italian nighttime balcony singing, replete with accordions and tambourines, became the bright point of quarantine solidarity, and everyone knew the virus was headed for Missouri since it had already hit New York, and was developing in Chicago. At first, local gatherings over 1,000 were canceled, then 100, then 10. Much of the Midwest held on to a sliver of hope that our lower-density region might fare better than the big cities. Maybe we could pull up the drawbridges, as St. Louis did during the 1918 Spanish influenza, and isolate from the rest of the world; maybe our rusty, hollowed-out downtown would form a rampart against the wave.

Asymptomatic, the elder sister landed in Chicago and boarded an Amtrak train to St. Louis. She quickly began to show symptoms, and on Thursday, two days before the dance, she “went to Mercy Hospital and was evaluated before being sent home to quarantine with her parents, who were not showing any signs of sickness.” She was tested, her Amtrak train was taken out of service to be cleaned, and a quarantine request from St. Louis County was, reportedly, issued that Thursday, March 5th. Her “presumed positive” case was widely reported on Friday.

Panic set in on Sunday, March 8th, as attendees of the dance—some of the richest families in St. Louis—were ordered by the County Executive to quarantine inside their $800,000 estates. The Ritz-Carlton shut down to sterilize its ballroom, bathrooms, and kitchen. Before the dance, the father was rumored to have visited Deer Creek Coffee near their house in Ladue—locally referred to as La-douche, one of the wealthiest zip codes in Missouri. The coffee shop was forced to publicly deny having served the father. St. Louis County Executive Dr. Sam Page, MD, held a press conference that underplayed the point: “From everything we can gather, the patient had conducted herself responsibly and maturely and she is to be commended for complying with the health department’s instructions.” He added, “The patient’s father did not act consistently with the health department’s instructions.”

The family’s attorney, Neil Bruntrager, materialized to dispute every detail: “These poor people are being pilloried and vilified,” he said. “They were being proactive. They were trying to deal with this problem.” Bruntrager, incidentally, was a well-paid legal representative of both STL Police Officer Jason Stockley, who murdered twenty-four-year-old Anthony Lamar Smith, and Officer Darren Wilson, who murdered Michael Brown.

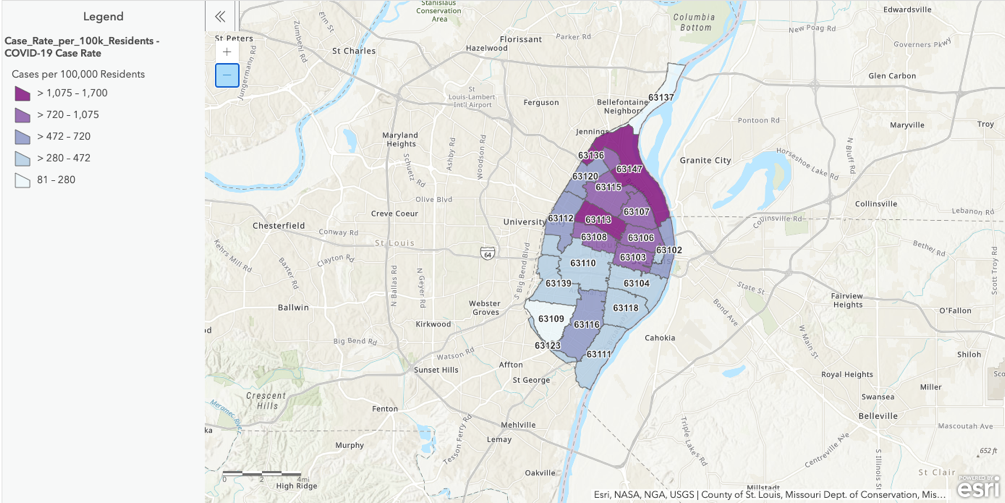

Starting with St. Louis’ white upper class, COVID-19 spread quickly to the working-class communities. So far, a disproportionate number of cases and deaths have been—much like the victims of police brutality—working-class Black St. Louisians.

Villa Duchesne, the private school that sponsored the daddy-daughter dance, is a lavish institution built like a castle in a leafy Frontenac neighborhood lined with mansions. Students drive luxury cars past the tennis courts to brick-laid lots near the verdant practice lawns for lacrosse and field hockey. With annual tuition ranging from six to twenty-three thousand, Villa is the third most expensive private school in St. Louis. Churchill Center & School is number one at thirty-five grand a year.

St. Louis school privatization began with the Catholic Church but has since moved on to be funded by a billionaire psychopath named Rex Sinquefield (Post-Dispatch reporter Tony Messenger writes, that Sinquefield wants to privatize St. Louis’ largest public asset, the airport, and uses a dummy organization called “Pedopolis” to lobby against Medicaid expansion). There are hundreds of private high schools in the county and city, private charters have a foothold, and the few public schools with proper funding are located in white, wealthy municipalities like Clayton and Ladue. The rest of the public education system is starved.

On top of looting the public system to finance exclusive private schools, the St. Louis aristocracy insists on continuing old-fashioned female purity traditions. Villa’s daddy-daughter dance is one example, but wealthy St. Louisians also participate in the Veiled Prophet Debutante Ball or the Archbishop’s Fleur-De-Lis Dance. The VP of the Veiled Prophet Ball is a hooded ruler from Khorassan who crowns a Queen of Love and Beauty once a year, and was originally used in 1877 as a strike crushing symbol during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The Fleur-De-Lis Dance has the Archbishop crowning the debutants because, historically, Catholics were kept out of the VP Society along with Jews, women, and anyone who wasn’t white.

The Villa fiasco confirmed suspicions that the rich white people of St. Louis don’t believe they live under the same law as everyone else, and possibly not even in the same civilization. St. Louis is one of the most segregated cities in America: on the south side of Delmar Boulevard, professors at Washington University and many white residents raise families in historic, oak shaded neighborhoods with old-timey gas lamps. North of Delmar, St. Louis’ Black community has endured hundreds of years of oppression. Most white St. Louisans don’t even know the highlights: the demolition of the failed Pruitt-Igoe public housing project in the 1970s; the racist destruction of Mill Creek Valley—a middle class Black suburb—to build Interstate Highway 40; the 1917 East St. Louis Riots, where uncounted hundreds (possibly thousands) of Black St. Louisans were killed and driven from their burning neighborhoods in what most historians would call a pogrom. These are rarely, if ever, taught in any school like the white private high school I attended, Christian Brothers College. I was fortunate to attend St. Roch, a fairly integrated elementary school near The Delmar Divide, but these events are never a part of the curriculum.

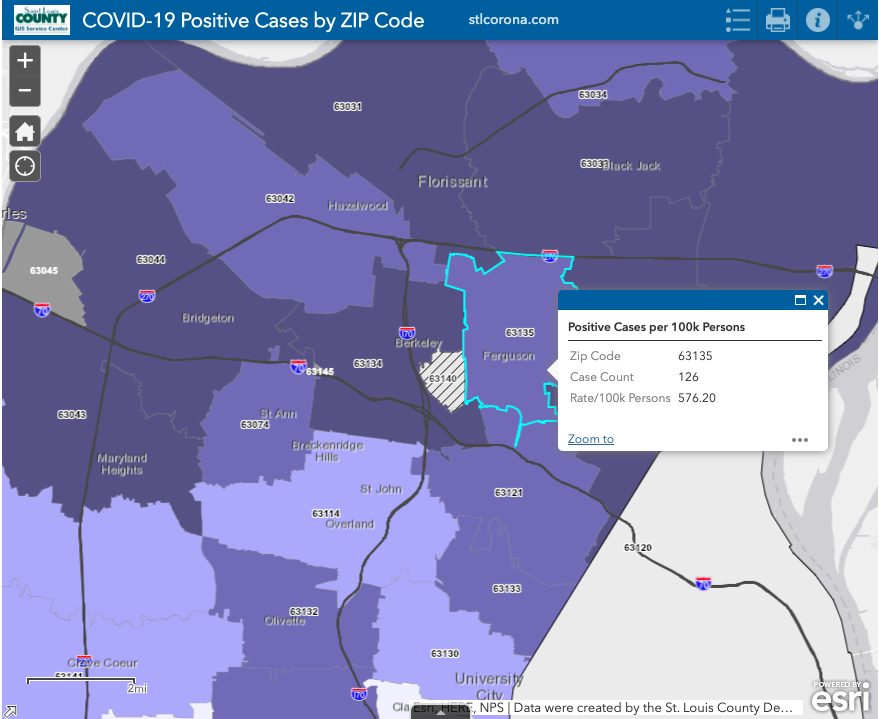

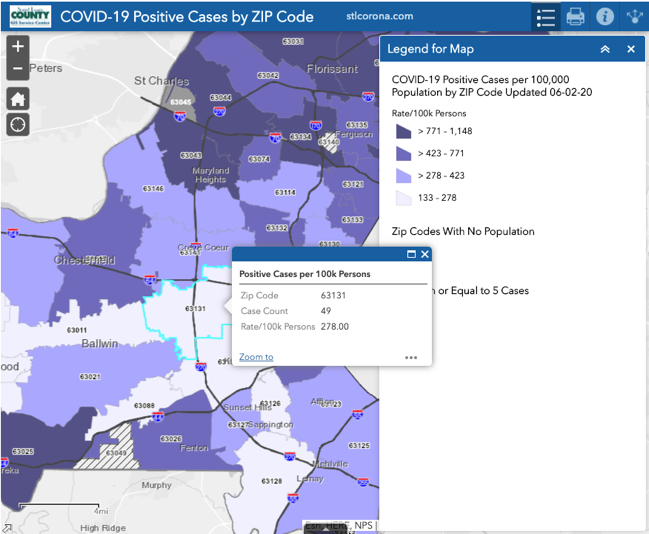

Just as you can overlay maps of household income with hot spots for lead paint, and chart payday loan offices on the dividing lines between white and Black neighborhoods; so can you overlay maps of COVID-19 and trace the jagged contours of segregation in St. Louis and other rust belt cities. As Colin Gordon, Walter Johnson, Jason Q. Purnell, and Jamala Rogers wrote in The Boston Review in May: “…in the city of St. Louis, African Americans account for 47 percent of the population, almost three quarters of COVID-19 cases, and it appears almost everyone who has died of the virus has been black.” Richer zip codes show lower infection rates as treatment and isolation is easier in gated private communities, but North St. Louis was written off the books long ago: “Many in black St. Louis point to the early 1970s as the beginning of the end for North City,” write Gordon et al. “In response to a 1973 RAND Corporation report, future United States congressman and Democratic presidential candidate Richard Gephardt introduced to the Board of Aldermen a motion declaring North St. Louis ‘an insignificant residential area not worthy of special maintenance effort.’” In neighborhoods like Northwood, Wellston, or Dellwood up by Ferguson—where people are more likely to be essential truck drivers, grocery store workers, and childcare professionals—the infection rate remains high.

As argued by the economic researcher Richard Rothstein in his 2017 book, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, these racial injustices are strategic. After the 1916 pogrom in East St. Louis, the Great Migration of Black people into St. Louis City accelerated. The downtown riverfront became dominated by former freed slaves and 1916 survivors while North St. Louis above Delmar also became predominantly Black. After World War II, all-Black towns like Kinloch and The Ville prospered as a kind of separate economic engine in the city where a Black couple could start and raise a family in an all-Black neighborhood, send them to an all-Black elementary school, high school, and then college at Harris-Stowe University—all without leaving North St. Louis. Black hospitals had previously been non-existent, but Homer G. Phillips Hospital trained doctors and nurses who served the community from the 1940s up to foreclosure in the 1970s.

Today there is not much left of Kinloch, North City, or The Ville. The area was transformed by deindustrialization and deliberate sabotage: the historic brick houses have fallen into a state of disrepair or are deconstructed because the bricks are worth more than the walls. Part of St. Louis’ red-lining strategy rests on the historic division between the city and the county; a line which exercises a distorting influence on everything from taxes to census data.

Combine these two districts, and the St. Louis population soars to 2.7 million—closer to the size of Houston or Phoenix. But because St. Louis has a million municipal divisions, it’s often ranked among smaller cities, and held to a lower standard, except when it comes to things like violence and STDs/STIs. In violence, poor health, and police funding, STL is always near the top.

In the weeks after the father-daughter dance, as the coronavirus spread, St. Louis County became Missouri’s most infected area. Ferguson has been particularly affected: and this is, of course, where Darren Wilson murdered Michael Brown.

Missouri’s Governor, Mike Parson, came to office after the former governor, Eric Greitens, was accused of blackmail. Greitens, a married man, allegedly invited a hair stylist he’d met over to his house, and then blindfolded her, bound her hands together, and photographed her naked body all without her consent, threatening to share the pictures if she ever went public with the “affair.” Compared to Greitens, who campaigned with fiery anti-Obama rhetoric and starred in a television ad firing a minigun, Parson portrays himself as a simple, boring Republican farmer.

At the beginning of May, against all public health advice, Parson was one of the first governors to lift the coronavirus lockdown. Even the blue islands in the sea of red Missouri—Kansas City, Columbia, and St. Louis—planned to reopen long before public health officials said it was safe.

One week later, the state made national news as bar-pools in the Lake of the Ozarks* filled up with “liberate Great Clips” types and partiers. Just as Missouri was found to be one of the states fudging its testing numbers, images of the Memorial Day Weekend at bars like Backwater Jack’s appeared to flout social distancing in favor of Fireball shots and Busch Lights. Following the example of the family who broke quarantine to attend the daddy-daughter dance at Villa Duchesne, the overwhelmingly white demographic at Shady Gator’s Cajun bar & grill displayed a big middle finger to the public. Horny, conservative suburbanites were tired of lockdown; they wanted the privileges of the rich.

That Saturday, COVID-19 racked up 250 new state cases. The liberal class defaulted to finger-wagging: Rachel Maddow pilloried the MAGA people behaving badly. (Katherine Cross, social critic and a PhD student at the University of Washington’s Information School, tweeted it best: “You are being set up to blame each other for the spread of COVID-19 to distract you from the deliberate failures of governments and corporations who’ve contributed far more to the pandemic.”)

It is never wise to fight political battles against parties, fun, or pools in the sun. In the backlash, Missouri’s simple country governor came out and mocked the idea that he’d use his power to stop the parties: “I’m not going to send the highway patrol out to monitor this.”

Not one week after the Ozark incident, the Minneapolis protest wave came to St. Louis. Overnight, Parson discovered he was perfectly comfortable deploying the National Guard to every city in his jurisdiction; he dispatched units at home, and sent some to Washington, D.C. for the first time since 1861. Squadrons of Black Hawk helicopters found their way to St. Louis. The mayor announced a curfew.

On May 28th, the Minneapolis police department burned to the ground, and by Sunday May 31st things were very tense in St. Louis. Protesters and police clashed, shop windows were broken and boarded up with plywood, a 7-11 burned, and 29-year-old Barry Perkins was caught in the gap between a FedEx semi truck’s containers during a shutdown demonstration on Interstate Highway 40. He dragged to death on that highway.

On Monday, June 1st, the Attorney General lied and said the city was releasing looters and rioters from jail without prosecution as COVID cases north of The Delmar Divide went up and up. The message was clear: The coronavirus reversal was short-lived. No matter how many rich people were out coughing on their pedicurist, downtown and North St. Louis went back to being dangerous hot zones in the minds of white St. Louis. Now the black neighborhoods were full of violent crime, looters, and the coronavirus.

It is almost too on-the-nose that the family who attended the Villa Duchesne dance chose Darren Wilson’s attorney to run interference for them; interference required because the rich didn’t want to miss a soirée. But St. Louis is a city of stark contrasts where gears of white supremacy and unjust division are a little more exposed, and a little more cartoonish with villains and heroes.

On Friday, June 26th, the St. Louis City Mayor Lyda Krewson took time out of a public Facebook Live briefing on the city’s coronavirus problem to read out the full names and addresses of Black Lives Matter activists. The activists had mailed her letters demanding police reform: “So they presented some papers to me about how they wanted the budget to be spent,” Krewson said, putting on reading glasses. “Here’s one that wants $50 million to go to Cure Violence, $75 million to go to affordable housing, $60 million to go to Health and Human Services and have zero go to the police. So that’s [REDACTED] who lives on [REDACTED] wants no police — no money going to police.”

Krewson claimed she didn’t know an alt-Right rally had drawn white supremacists to the city that night. There was a rally planned for Saturday, June 27th . The alt-Right and conservative Catholics were going to show up at the statue of St. Louis outside the public Art Museum and keep protesters from tearing it down. Not only were the neighborhood Proudboys activated, but the spectacle attracted freaked-out Right wingers from all over.

Mayor Krewson is a Democrat (i.e. center-right Republican adjusted for Missouri standards) and has now presided over three waves of protests met with militarized suppression, violent police kettleing still under litigation, tear gas, the suspicious deaths of Ferguson activists, and now doxxing.

On Sunday June 28th, to return fire for the Facebook Live incident, hundreds of protesters marched toward the mayor’s house to paint “RESIGN” on Lyda Krewson’s street. A couple of gun-swinging personal injury lawyers threatened the crowd outside their enormous mansion from behind a private gate.

Mark and Patricia McCloskey were memed into national news shortly after confronting the protest group. Neither wore shoes. A mostly-drunk pitcher of pink beverage sat on their veranda. Mark tucked his salmon Brook’s Brothers polo into his slacks for a Sunday in quarantine, and over his chubby belly, he rested an AR-15 which was in his hands long before the protestors opened the Portland Place gate. Contrary to some knee-jerk reporting, protesters did not break the gate down, it was open.

Patricia, taller than Mark with less trigger-discipline, wore a white and black hamburglar striped shirt with a large mustard stain on the shoulder. She defended her lawn with a small silver pistol pointed directly at protestors, finger on the trigger, marching and screaming about private property. The couple appeared inexperienced with their firearms, and the leaders of the unarmed protesters were forced to de-escalate the situation.

The scene created incredible images; a tense moment where the lawyers could have easily shot each other by accident, or worse, a protestor.

More absurd information about the McCloskeys followed the incident including a mile-long list of lawsuits carried out against fellow mansion owners in the neighborhood, trustees, family, and anyone foolish enough to do business with Mark and Patricia, or live behind them; “In 2013, [Mark] destroyed bee hives placed just outside of the mansion’s northern wall by the neighboring Jewish Central Reform Congregation and left a note saying he did it, and if the mess wasn’t cleaned up quickly he would seek a restraining order and attorneys fees. The congregation had planned to harvest the honey and pick apples from trees on its property for Rosh Hashanah.” “‘The children were crying in school,’ Rabbi Susan Talve said. ‘It was part of our curriculum.’”

The McCloskeys don’t represent St. Louis. They do represent an aspect of the St. Louis rich who have all the money, all the guns, the biggest stone houses full of expensive things, and remain five-alarm terrified of their neighbors peacefully protesting, calling for justice and a fairer city.

The protest crowds in St. Louis have been particularly massive because they’ve activated a network of organizers which was first developed in the wake of 2014. As one of the catalyst cities for the Black Lives Matter movement, St. Louis already has politicians, staff, and best-practices for controlling the street with peaceful demonstrations. Within days, a legal group called the ArchCity Defenders published a five-point list of demands including “Close The Workhouse.” The Workhouse is a Jim Crow relic of a prison where poor, mostly black, inmates are held in squalid, illegal conditions. Not because they’ve been convicted of a crime, but because they are awaiting trial and cannot afford bail.**

On Thursday, June 4th, hundreds of St. Louisans assembled in a big-box parking lot called the Brentwood Promenade. Haunted by a police helicopter overhead, and with the Brentwood stores boarded up lest someone loot the PetSmart, the protest crowd blocked traffic on the big roads nearby.

Most protesters knew nothing about the small plaque in the corner of the Brentwood Promenade. A small memorial there commemorates the African American neighborhood which many called home until the late 1990s, before the Trader Joe’s and Target went in. Like Mill Creek Valley in 1959 which was home to some 20,000 Black St. Louisans, minority neighborhoods in the city and county are erased in the name of big-box progress. It’s the most familiar pattern in St. Louis history: to build the Arch, the Black wharf neighborhoods that serviced the river docks were wiped clear. To build the Cardinals’ baseball stadium, St. Louis’ first Chinatown was demolished. In 1991 a St. Louis county municipality called Kirkwood voted to annex the mostly-Black Meacham Park*** and systematically pushed Black residents out. The failed Pruitt-Igoe housing projects remain a historic, unaddressed wound in the St. Louis Black community.

“Our purpose is to heal our community and build our community,” organizer and congressional candidate Cori Bush said in the Brentwood Promenade**** in front of the Target. Bush is running to unseat Lacy Clay—a do-nothing Democrat seat that the Clay family has held for decades, first Bill Clay and now Lacy. Cori is a nurse, a pastor, and an on-the-ground Ferguson activist who likely survived COVID-19, got pepper sprayed by the Florissant Police, had her car shot up, and got a slew of death threats for speaking against the gun lawyers, and that’s all within the last two months.

More signs of growth: On Tuesday, June 2nd, 2020, Ferguson elected its first Black female mayor. The Ferguson Report remains on the desk of every elected official, collecting dust, largely unimplemented, but new progressive candidates are organized and running for office. Tishaura Jones, my hero, is set to remain city treasurer; STL DSA endorsed candidate Megan Green is running for State Senate; it looks as though Cara Spencer will run to Lyda Krewson’s left for the mayor’s office.St. Louis has endured a hundred years of economic decline. Segregation holds the city back from ever being a better place, and the city leaders have committed untold evils against the communities that make St. Louis a beautiful, welcoming, creative place to live. For every Mark and Patricia, for every Lyda Krewson and rich family breaking quarantine, there are ten-thousand more living peacefully, working hard, building a better future. The toughest, bravest activists live and fight in St. Louis, and while some cities are having their first BLM marches, STL is decades into the game.

* The Lake of the Ozarks is a get-away for suburban Missourians; a vacation spot deep in MAGA country, about three hours from the city by car.

** As of July 17th, 2020, the St. Louis Board of Aldermen voted to close The Workhouse.

*** It’s a complicated story, but one resident of Meacham Park was Cookie Thornton who ended up embroiled with Kirkwood city hall for years. Feeling harassed, unjustly ticketed, and silenced, in February 2008 Cookie went to the city hall building and shot and killed six people, injured two, and was killed by the police.

**** A man in a pick-up truck was later arrested for driving through the crowd at the start of the protest, and as he sped away, loud pops were heard—later it was confirmed he shot a gun out the window without hitting anyone.

PHOTO: Armed homeowners Mark and Patricia McCloskey, stand in front their house along Portland Place confront protesters marching to St. Louis Mayor Lyda Krewson’s house in the Central West End of St. Louis. (Bill Greenblatt/ UPI)