J.K. Rowling and the Limits of Imagination

The creator of Harry Potter could imagine the most marvelous fictional universe in children’s literature—yet she can’t imagine the inner lives of transgender people or the radical expansion of political possibilities.

[content warning: sexual violence, transphobia]

Hagrid. Polyjuice Potion. Hogwarts. Diagon Alley. Platform 9 and ¾. The Dursleys. Butterbeer. Dementors. The Whomping Willow. Moaning Myrtle. The Golden Snitch. 75 wonderfully named spells from Wingardium Leviosa to Repelo Muggletum. A whole miraculous and intricate world, unfolding over 1,084,170 words, a world to which hundreds of millions of children speaking 80 different languages dreamed of being transported. And all from the mind of a single person, J.K. Rowling.

I do not think it is inaccurate to say that the Harry Potter series proved J.K. Rowling to be one of the most brilliantly imaginative writers who has yet lived. A lot of things you may have loved in childhood tend to look like shit once you are grown up. But the seven Potter books look more, not less, impressive to my adult self than they did to me as a child, because I’m a writer now and I know how painful and time-consuming it is to produce even a single page of really high-quality prose. The haters like Harold Bloom—who thought Rowling’s writing was cliche-ridden because characters sometimes “stretch their legs”— have never had a case. The bad reviews always sounded bitter, resentful, and frequently sexist.

You can shit on Harry Potter if you like, but those of us of a certain age remember the midnight release parties and we remember how quickly we devoured the new installment through a frenzied night. Who else has ever been able to produce this intoxicating effect on so many children with mere words? Will anyone else ever do anything like it? J.K. Rowling made a contribution to the culture that will stand for a long time.

But Rowling is also a bigot. Over the last few years, she has steadily turned off many of her fans by making increasingly harsh remarks about the transgender rights movement, culminating in an essay on her website in which she warned that trans activism is dangerous and offers cover to sexual predators. Actors in the Harry Potter films, along with famous Rowling fans like Stephen King, have distanced themselves from her or condemned her comments. Some fan websites have now taken Rowling’s information down, trying to find a way to enjoy the text while forgetting its writer. But “death of the author” is difficult when the author is alive and regularly tweeting offensive comments, discomforting those who are politically progressive but who were deeply affected by the Potter books as kids. Rowling’s essay on trans activists is an ugly thing: bitter, accusatory, cruel. All of the enchantment has vanished. As Zinnia Jones wrote at Gender Analysis:

In the absence of a byline, there would be nothing to indicate that this was produced by the creator of a beautiful fantasy world that captured the hearts of children and adults the world over. There is not a hint of transcendence, imagination, or humanist care for the well-being of others to be found here; it is a base and shameless exhibition of the worst tendencies of fear, ignorance, and dehumanization.

How did we get from the one place to the other? How did we go from the “beautiful fantasy world” to this exhibition of fear and dehumanization? Was she always like this? Why is she doing this? People who always detested the books can give fans a satisfied “I told you she sucked,” but this is far too simple. Rowling’s fiction is complex, thoughtful, deeply beloved. That has to be reconciled with any explanation of her ignorance on gender.

I.

I actually want to first spend a little bit of time on the achievements and appeal of the Harry Potter series, and what it has meant to millions of children and adults, because I think it’s actually necessary to understand what Rowling is capable of in order to take stock of what she isn’t capable of. I do not mean this as “she might be transphobic, but let’s talk about how great Harry Potter was.” What I want to discuss is the contrast between the greatness of Harry Potter and the narrowness of Rowling’s prejudices, and what this indicates about liberal ideology and how difficult the pursuit of social justice can be.

I went back to the series to try to remember exactly how Rowling hooks people so quickly, and one thing that surprised me was how unpredictable the first Harry Potter book is. We begin with Vernon Dursley, who is trying to have a normal day but sees a cat reading a map. Before we even get to Harry, who doesn’t really show up until chapter 2, we see Albus Dumbledore explaining the concept of lemon drops to Minerva McGonagall. I love this. It’s bold. A conventional writer would have begun with something like: “Harry Potter did not know he was special.” Rowling began: “Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much.” Rowling is often compared with Roald Dahl, but I went back and looked at James and the Giant Peach, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, The BFG, and George’s Marvelous Medicine. The first page of each introduces the main character—James, Charlie, Sophie, and George, respectively. Rowling does it differently. She tells you things that don’t make sense, so that you want to find out what they mean. (I suspect one reason so many publishers turned it down is that they quickly went “What the fuck is this about?” and shut the book. Publishers are very conservative.)

There is so much crammed into that first short volume. Harry’s failed attempts to be a normal boy in the world of Muggles, accidentally letting a boa constrictor loose from the zoo. The letters that pursue him. The entrance of Hagrid. Finding out about his parents. Amassing supplies at Diagon Alley. The Hogwarts Express, meeting Ron and Hermione, making an enemy of Malfoy, getting Sorted, meeting Dumbledore, an introduction to the whole range of classes and professors, plus Quidditch. Somehow in the second half she manages to fit in the entire Philosopher’s Stone story.

Why did the Harry Potter series succeed so well? Why do so many people love it? Well, because it has everything you could ever want in a piece of escapist fiction. The premise, stated in its simplest form, is genius: a boy who doesn’t know he’s a wizard. But from that premise, which was the first thing that popped into her head, she spun out an entire elaborate universe with 772 characters, and built up what starts off as a series of adventure stories (the first three books) into a grand, sweeping epic (the last four) about death, love, memory, friendship, power, and coming of age. Rowling deftly mixed together just the right ingredients: orphan protagonist (a must in children’s literature), boarding school story, humor, drama, mystery, thriller, plus almost every magical thing in the history of Western mythology and folklore. Giant spiders! Centaurs! Dragons! Giants! Ghosts! Goblins! Phoenixes! Werewolves! Gnomes! Creatures of Rowling’s own invention, like the terrifying soul-sucking Dementors. (This is just the beginning.) The characters are both complex and memorable. (Who can forget even secondary figures like Rita Skeeter, Gilderoy Lockhart, and Dolores Umbridge after meeting them?) Voldemort, the Shrieking Shack, the Forbidden Forest are all good nightmarish stuff, but Rowling is also funny (Harry is assigned Muggle Studies essays like “Explain Why Muggles Need Electricity” and “Witch Burning in the Fourteenth Century Was Completely Pointless — discuss”) and she peoples her world with eccentrics (Albus Dumbledore, when we first meet him: “Scars can come in handy. I have one myself above my left knee that is a perfect map of the London Underground.”) Revisiting the books I found myself laughing aloud at the silliest little details (a Muggle news reporter: “The nation’s owls have been behaving very unusually today…”)

Rowling also makes readers drool when she writes about food:

“He had never seen so many things he liked to eat on one table: roast beef, roast chicken, pork chops and lamb chops, sausages, bacon and steak, boiled potatoes, roast potatoes, fries, Yorkshire pudding, peas, carrots, gravy, ketchup, and, for some strange reason, peppermint humbugs.”

Everything is memorable in the books, from the lightning scar to the House colors, and I am sure that nearly anybody who doesn’t come into them with a sneering expectation of hating them can find some aspect of the books to enjoy. There are also endless “personalized” elements that allow children to imagine their own place in this special world, which is probably part of why so many children find them comforting. (Which House would you be in? What would your Patronus be? Your Boggart? What would you see in the mirror of Erised? What would the Amortentia potion smell like to you?) Personally, I never really cared about the plots (which is why I rather lost interest by books 6 and 7, which are heavy on exposition and got too complicated for my taste). I just wanted to spend time in the book’s universe, to ride on the Knight Bus and eat Bertie Botts’ Every Flavour Beans (“toast, coconut, baked bean, strawberry, curry, grass, coffee, sardine,” to name only a few).

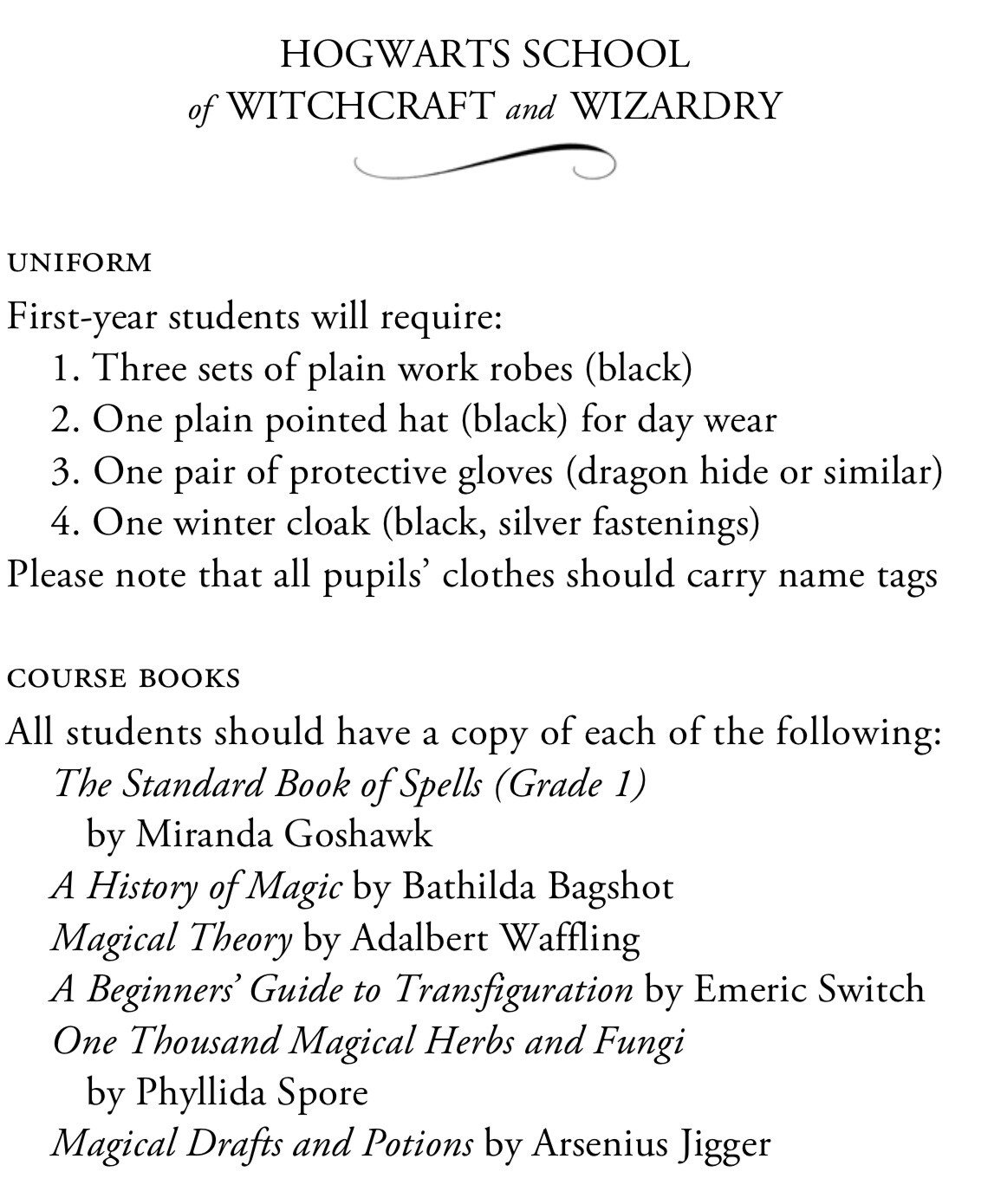

Rowling has a singular way of combining mundanity with magic, so that the wizarding world feels relatable on account of its absurd mixture of the typical and the utterly daft. I was never into “fantasy” literature as a child because its worlds felt too distant, and one of Rowling’s masterstrokes was to build hers in the nooks and crannies of our own. An ordinary wall in a train station becomes a potential portal to a secret platform. A fireplace might be a teleportation device, if you have a bit of floo powder. The British government has a secret Ministry of Magic along with its Ministry of Defence and Ministry of Housing. Rowling enchants not just ordinary things, but deeply boring and extremely British things (e.g. a Ford Anglia), and even her most enchanted things have elements that are bureaucratic, formalistic, and dry. Nowhere is that deployed to better effect than in the list of required school supplies Harry is sent in advance of his enrollment at Hogwarts:

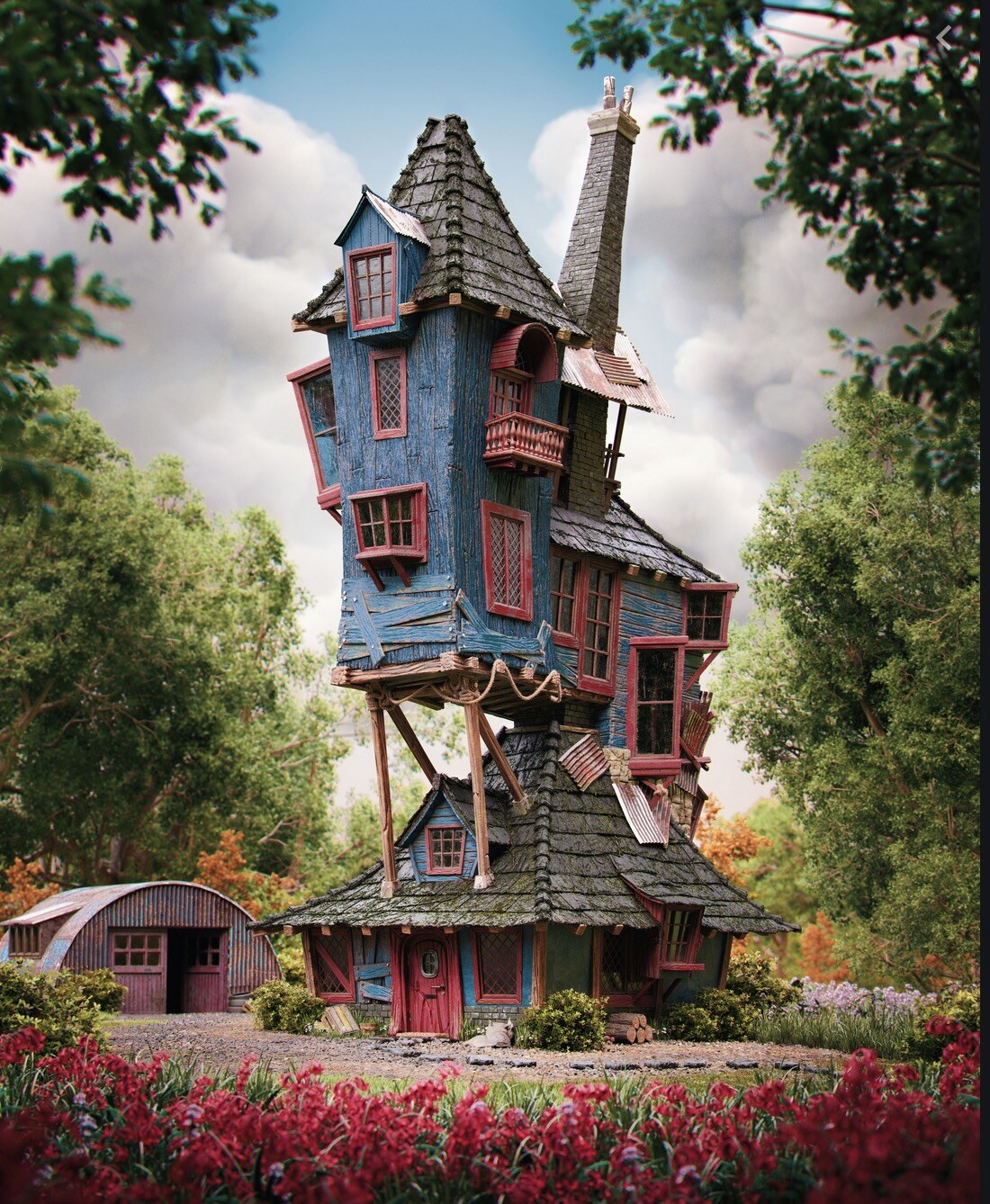

I defy you to tell me that isn’t perfect and hilarious. We’re so used to Harry Potter now that I don’t know if we still notice just how creative Rowling was. Fantastic Beasts and Where To Find Them is now the title of a shitty big-budget film franchise, so it’s easy to forget what a great name that is for a textbook at a wizardry school. In fact, just consider the number of things Rowling had to invent. Types of broomsticks (Nimbus Two Thousand, Firebolt, Comet Two Sixty). Names of Quidditch teams (Chudley Cannons, Quiberon Quafflepunchers, Caerphilly Catapults). Rules of Quidditch (the scoring system makes no sense, but that’s probably the point). Plants (Gillyweed, Bubotuber, Shrivelfig, Mimbulus mimbletonia). Potions (Skele-Gro, Polyjuice, Veritaserum). Magical objects (Invisibility Cloak, Marauder’s Map.) Wizard currency (Knuts, sickles, galleons). Wizard journalism (The Quibbler, The Daily Prophet). Offices of the bureaucracy (Department of Magical Accidents and Catastrophes, Department for the Regulation and Control of Magical Creatures.) Places (Little Whinging, Knockturn Alley, The Burrow.) The places are often unforgettable, as can be seen in the fan art they inspire:

And of course there are the endless little touches, like the fact that wizards move in photos, the cards that come with chocolate frogs, or the gnomes that inhabit the Weasley garden. And who can make a list like Rowling?

- “They left Zonko’s with their money bags considerably lighter than they had been on entering, but their pockets bulging with Dungbombs, Hiccup Sweets, Frog Spawn Soap, and a Nose-Biting Teacup apiece.”

- “Barrels of slimy stuff stood on the floor; jars of herbs, dried roots, and bright powders lined the walls; bundles of feathers, strings of fangs, and snarled claws hung from the ceiling. While Hagrid asked the man behind the counter for a supply of some basic potion ingredients for Harry, Harry himself examined silver unicorn horns at twenty-one Galleons each and minuscule, glittery-black beetle eyes (five Knuts a scoop).”

- “There were shops selling robes, shops selling telescopes and strange silver instruments Harry had never seen before, windows stacked with barrels of bat spleens and eels’ eyes, tottering piles of spell books, quills, and rolls of parchment, potion bottles, globes of the moon…”

- “What she did have were Bertie Bott’s Every Flavor Beans, Drooble’s Best Blowing Gum, Chocolate Frogs, Pumpkin Pasties, Cauldron Cakes, Licorice Wands, and a number of other strange things Harry had never seen in his life. Not wanting to miss anything, he got some of everything.”

Perhaps most impressively of all, Rowling is a true artisan of aptonyms, names that are just right for a thing. Slytherin. Hufflepuff. Possibly she’s the best at these since Charles Dickens. Possibly she’s even better at them than Charles Dickens. What names her people have! Cornelius Fudge, Filius Flitwick, Gellert Grindelwald, Bellatrix Lestrange, Mundungus Fletcher, Xenophilius Lovegood, Kingsley Shacklebolt, Flourish and Blotts, Pomona Sprout, Dedalus Diggle, Wilhelmina Grubbly-Plank, Nymphadora Tonks, Bathilda Bagshot, Argus Filch. The trick with these is sometimes obvious—severe, snake, snap, snipe: Severus Snape. Draco Malfoy—Dracula. Got a harsh “K” sound in it. Got a ffff sound. Mal: bad. Or Voldemort—V’s are threatening letters. Carving a v into something has a menace that carving a Q will never have. Mort: death. But there’s three letters of “evil” in there as well. Umbridge—obvious. And so on. You may think this sounds a lot like naming your villain Eli V. Badperson. But here’s an exercise: you try coming up with a character with a name that instantly forms a picture of them in another person’s mind. The first one I did was Ralph Thicketty, a rotund economist who throws up a lot. Utterly terrible. I was not made for the world of children’s literature.

(Sidenote: I assumed it must have been fun for foreign translators to have to render the Harry Potter universe into other languages, but actually I looked it up and not so much. Quite tedious and difficult actually, with extremely unsatisfying results.)

All of which is to say: J.K. Rowling’s talent as a writer is immense. She has a gift. And not only that, but she triumphed against considerable odds. Britain is a sexist, classist society and Rowling was a poor single mom. She couldn’t even publish under her actual name—her publisher asked her to use initials so that readers would not know she was a woman. Before all the online transphobia, Rowling herself was adored, in part because she seemed an example of a “meritocracy” actually functioning: a talented woman producing something actually good and then getting rightly acclaimed for it. Fans wanted to love J.K. Rowling. They did love J.K. Rowling.

This is a critical part of why so many of her readers feel so betrayed to see Rowling devolve into a Twitter personality who regularly says offensive things about transgender people. To have invented all of this… and then to become that? How disappointing. How sad. How typical. How distinctly non-magical. Rowling’s Twitter feed is mostly her reactions to children’s charming fan art (or her attempts at reactions). But then it alternates with something different, something gross. Something that instantly makes the magic disappear.

II.

Let us establish very clearly: J.K. Rowling is transphobic. This is beyond serious dispute.

As Julia Serano—a PhD biologist who has spent years patiently trying to clear up misconceptions and debunk anti-trans arguments, and who I will cite frequently because I think she is the single best source of clear explanations of the basics of sex and gender—explains, “transphobia,” like “homophobia” and “Islamophobia,” does not always refer to a phobia like agoraphobia or arachnophobia, though many people do have this kind of irrational aversion to trans people. Transphobia refers to a prejudice against transgender people, often manifested through “the belief or assumption that cis people’s gender identities, expressions, experiences, and embodiments are more natural and legitimate than those of trans people.” (Serano has a comprehensive glossary and dozens of explainer essays for those who wish to gain an understanding of what they are talking about before they try talking about it.)

Does J.K. Rowling exhibit this kind of transphobia? Absolutely. When she talks about gender politics, she is often indistinguishable from Ben Shapiro.

In her widely-criticized essay, Rowling says she is speaking up for women who oppose “allowing any man who says they identify as a woman into the women’s changing rooms” and that the “trans rights movement” is “offering cover to predators like few before it.” This is an incredibly dangerous thing to say, stigmatizing transgender people as predators and the enablers of predators. She cites no evidence to support it, because it’s simply bigotry. She tells the usual fear-mongering tales that conservative Republicans tell about the perils of having trans women in the bathroom:

When you throw open the doors of bathrooms and changing rooms to any man who believes or feels he’s a woman—and, as I’ve said, gender confirmation certificates may now be granted without any need for surgery or hormones—then you open the door to any and all men who wish to come inside.

As my colleague Adrian Rennix has written, this is ridiculous: people who wish to commit sex crimes in bathrooms do not have their gender checked at the door. A person does not have to “pass” as a woman to commit a crime in the ladies’ room, they just have to walk into the ladies’ room.

More importantly, she does not consider that her own framework for bathrooms, by wanting trans women to use the men’s room, will create the exact abuse situations that she says she is worried about—and every day instead of rarely. We have some data suggesting that forcing trans people to use the wrong bathroom increases their risk of being assaulted, which is what you’d expect. Why is the fear experienced by trans women forced to use a bathroom for the opposite gender not present in her framework? Because J.K. Rowling is transphobic, and trans women’s experiences are seen as less legitimate.

Furthermore, when we talk about what “throw open the doors” and “allow” actually means in practice, it means law. So to be clear, Rowling is saying that transgender women would be forced by law to use the men’s room. It is not clear how this would ever be enforced, but the only ways we can think of sound utterly horrible.

Rowling’s essay is maddening, in part because, a lot like “intellectual dark web” criticism of feminist and anti-racist politics (see, e.g, Steven Pinker), it pretends to be Reasonable and Empathetic but is nothing of the kind, distorting the opposing arguments and failing to actually engage with the other side’s writing or thinking. It is, as Dominique Sisley writes for Huck, “dogmatism dressed up as rationalism,” misrepresenting facts, making unsubstantiated claims, presenting unrepresentative anecdotes as data, and spreading pernicious myths:

She makes vague references to an “increasing number” of people detransitioning to their original sex and causing “irrevocable” damage to their bodies (all myths we, and many others, have previously debunked). In an attempt to paint her critics as irrational, Rowling makes emotional, sweeping statements that seem to have little grounding in reality, casting herself as a victim in a fight that she shouldn’t even have any place in. She mentions facing a tirade of online abuse for being “a TERF”—which includes being called a “bitch” and “Voldemort”—and uses the piece to conflate trans activists with incels and Donald Trump. She appears to disregard some of the vile language used by the more unhinged members of the TERF movement, who Rowling either follows or supports.

It’s quite clear that while Rowling insists she supports trans women, she fundamentally believes many of them are not actually women. Rowling backtracked when she “liked” a tweet calling trans women “men in dresses,” saying it had been an accident. This was perhaps plausible at first (I have liked tweets by accident before myself), but in her subsequent essay she talks about the problems she sees with letting “any man who believes or feels he’s a woman” be considered a woman, which is very straightforward: she thinks many who claim to be women are not in fact women. Rowling also posted a tweet insisting that “sex is real,” with the implication that many trans people are denying the reality of sex. (This is a very Shapiro-esque talking point.)

The implication here seems to be that while trans people think anyone who “feels” or “believes” they are a woman is a woman, in fact there is a thing called “sex” that determines it. Here, like Ben Shapiro, Rowling simply does not understand the argument being made, believing that trans people deny the facts of biological reality when in fact what they deny is the traditional way of categorizing those facts linguistically. As Natalie Wynn said in response to Shapiro, “It is not I who do not understand biology, it is you, Ben Shapiro, who does not understand language.” Gender and sex are complicated, but sex being “real” has nothing to do with the debate, since trans people acknowledge that chromosomal sex is real (though it is not actually a binary, “real” is a misleading/unhelpful term since all categorization schemes are constructed—reality is real but the terms we use to describe and understand it can be changed—and it is far more complicated than There Are Men And There Are Women). The thing this does is push the myth that transgender people are idiots who do not understand basic biology, when in fact many trans people have to understand and think more about the chemical makeup of the human body than cis people do. (Again, Serano has a PhD in biochemistry from Columbia and spent seventeen years researching genetics and evolutionary biology at Berkeley.) As trans writer Katy Montgomerie forcefully explained in response to Rowling:

Sex is real. I am a trans woman who knows hundreds of trans people and who is very active in the community, and I’ve never heard any trans person or expert say or imply otherwise even once. Trans people are often more keenly aware of sex characteristics than anyone else, having often spent their whole lives dealing with the dysphoria that their various sex characteristics cause them, and seeing how other people react to them. I, and almost every trans person I’ve talked to, have had to teach the doctors and nurses who aren’t experts how our biology works just to get basic healthcare. Often one of the main things that trans people want for the world is a better understanding of trans bodies and of biology.

But Rowling distorts these realities over and over throughout her essay, showing that she has no interest in being careful or fair. At one point she says: “The argument of many current trans activists is that if you don’t let a gender dysphoric teenager transition, they will kill themselves.” That makes it sound like an absolute. No, the argument made is that if you do not support teenagers when they state their gender preference, it can make their life a misery, leading to depression and possibly even suicide, which are the frequent results of misery.

A good deal of Rowling’s essay is devoted to the supposed giant problem of the “trans rights movement” capturing children and turning them into genders that they later decide do not fit them (and thus leading them to “detransition”). Remember how Serano discusses transphobia manifesting itself in giving legitimacy to the experience of cisgender people but not the experience of transgender people. Well, the “detransitioning” issue is exactly like that: focusing entirely on the small number of cases of those who end up cisgender, ignoring those who are happily trans.

Here’s another example of Rowling assuming transgender people must be crazy and wrong without listening to anything they are saying. Rowling discusses a paper by Lisa Littman on the subject of so-called “rapid onset gender dysphoria.” The paper was controversial, because it suggested children were turning transgender through a kind of peer pressure. Here’s how Rowling presents the facts:

Her paper caused a furore. She was accused of bias and of spreading misinformation about transgender people, subjected to a tsunami of abuse and a concerted campaign to discredit both her and her work. The journal took the paper offline and re-reviewed it before republishing it. However, her career took a similar hit to that suffered by Maya Forstater. Lisa Littman had dared challenge one of the central tenets of trans activism…

Rowling does something here that people often do when telling a story about the Social Justice Mob shutting down dissenting opinion, which is that she assumes that the critics must have been wrong without actually investigating what their criticisms were. Once again, we see how trans people are assumed to be crazy and anti-knowledge: those who accused Littman of spreading misinformation were clearly doing it because Littman had challenged their dogma, not because Littman hadn’t supported her controversial claims. Littman was “accused,” but were the accusers right? Here are detailed criticisms of Littman’s paper by Julia Serano, Brynn Tannehill, and Zinnia Jones. Surely the question is whether those critiques are accurate or not. But Rowling simply assumes they must have been a kind of hysterical angry irrationalism, because trans people are treated as unreasonable and guided by emotion/ideology instead of Reason. In fact, when the journal republished the article it was with corrections and revisions (and an apology for its errors), a fact Rowling is uninterested in telling her readers, because she selects her facts to make trans people look bad. (Of course, as happened after the retraction of a journal article defending colonialism, the apology and revisions will be treated as evidence that the journal “caved” to the “trans lobby,” rather than as evidence that trans people correctly pointed out methodological flaws.)

Rowling, then, is ignorant. She couldn’t be bothered to read an introductory blog post, let alone actually research the subject. Here she is explaining that while she has been begged repeatedly to actually talk to (and listen to) the people she’s talking about, she has made no serious effort to do so:

Again and again I’ve been told to ‘just meet some trans people.’ I have: in addition to a few younger people, who were all adorable, I happen to know a self-described transsexual woman who’s older than I am and wonderful.

Is this a bit? Is she joking? She is being asked to try to do some listening. Her conclusion is that young trans people are “adorable” and that the older trans woman she met is “wonderful.” Does she see that people will find this patronizing? Does she understand that the demand was not to see how cute trans people are, but to try to exhibit a greater understanding of those with experiences different than her own?

Near the conclusion of her essay, Rowling says she just wants “similar empathy, similar understanding, to be extended to the many millions of women whose sole crime is wanting their concerns to be heard without receiving threats and abuse.” Now, here I want to try to fulfill Rowling’s request for empathy, because it’s something I believe in. Rowling, toward the end of the essay, discusses her history of being violently abused. She talks about how sympathetic she is to transgender victims of violence by men, because she has felt the fear of male violence herself. The passage is moving and sensitive.

Unfortunately, immediately afterward, Rowling says she “believe[s] the majority of trans-identified people…pose zero threat to others” The “majority”? So what, like 40 percent of trans people might be a threat? Rowling then launches into her thing about throwing open the doors of bathrooms, and says that it is the “simple truth” despite having offered not a shred of evidence that this is an actual concern as opposed to a myth that is pushed by social conservatives to make people think of all trans people as potential predators.

I believe that Rowling believes her statements are only in the service of protecting women from violence. And she’s right that the abusive and violent comments she and other women receive are appalling, though she notes that the overwhelming public response to her wading into trans issues has been positive. (Which is some suggestive evidence that perhaps her “unpopular” opinion is in fact a highly popular prejudice, and it is trans people who actually have the “unpopular” perspective.)

People often do not notice their transphobia. They do not notice that they are applying different standards to trans people than they do to cis people. For instance, Serano points out that transgender people are often accused of reinforcing sexist stereotypes about women by associating the process of becoming a woman with femininity and embracing a “caricature.” But since the majority of cisgender people do this too, why do trans women get the blame?

Trans writers have carefully explained why what Rowling said is objectionable. In addition to Montgomerie’s piece, Zinnia Jones published a three-part series citing tons of peer-reviewed scientific literature. Do I think Rowling will read Jones’ careful explanation of how Rowling is misrepresenting statistics in order to present a picture of some giant national trend of children becoming transgender? Do I think she will bother to investigate the abuse that trans writers receive (here’s journalist Siobhan O’Leary on what she gets in just 24 hours) so that Rowling can fix her misperception that the online trans community is uniquely hostile? No, I think she is going to conclude that the existence of disagreement with her essay means that she must be telling Unspeakable Truths that No One Dares To Say. Shortly after publishing her post, Rowling became one of the most prominent signers of an open letter in Harper’s about supposed threats to free speech from leftist activists, which certainly doesn’t suggest she’s done much listening.

* * *

I know it’s a stupid question, but it does tend to cross our minds when we see those we once respected say indefensible things: how can someone who made something so wonderful produce writing so foul and stupid? The books she wrote were not just “good,” they required astonishing powers of thought and insight. Writing good characters requires a capacity for empathy, for getting inside the heads of many different kinds of people to understand how they think and feel. To make characters as vivid as she did, even though they are fantastical, you have to be able to ask: why does X person do what they do? What do things look like through their eyes?

Yet somehow Rowling cannot understand why trans people react with such hostility to her suggestion that self-identification is “offering cover to predators” and that only a “majority” of trans people pose no threat. Why?

I am fascinated by the idiocy of geniuses. Bobby Fischer and Garry Kasparov were two of the greatest players in the history of chess, but the former believed in wild anti-Semitic conspiracies and the latter thinks the Middle Ages didn’t happen. Noam Chomsky, who revolutionized linguistics and is possibly the most important living intellectual, cannot figure out the basics of how to use a Keurig, the world’s easiest coffee machine. Elon Musk… well, that case is different, he’s just quite stupid.

Part of it, then, is the incredibly banal fact that just because a person can do one thing very well doesn’t mean they can do anything else very well. I can edit a magazine well. I cannot write computer programs. The capacity to make up a lot of interesting wizards and the capacity to demonstrate basic empathy for transgender people are apparently quite different, and there is no reason to expect the two traits to coincide.

But a lack of awareness of the inner experiences of trans people is also not by chance. It is because we live in a deeply transphobic society, and when it comes to the topic plenty of otherwise sensible and intelligent people become little different from Donald Trump or Pat Robertson. (Actually, this is slightly unfair to Pat Robertson, who occasionally made better statements on transgender people than J.K. Rowling… though he soon reversed himself and lapsed back into his usual material.) Part of the problem, and this applies to transphobia, Islamophobia, and racism, is that people are still convinced that bigotry means “hate,” and that if they do not feel “hate” then they are not bigoted. But this is never how it has worked: except for hardcore white nationalists, racists have often claimed to care about all people. Martin Luther King was most frustrated by those who said they had his best interests at heart, and wanted to help but just disapproved of his methods. I was recently reading Langston Hughes’ memoir The Big Sea, and he discusses a wealthy white woman who served as his patron during the Harlem Renaissance. She simply adored him, but she also expected him to produce a very particular kind of writing that would capture the spirit of the “savage” and “African” that so entranced her about him. When he didn’t conform to her expectations, she cut him loose. She was a racist, it is obvious to any of us, but every word out of her mouth was about how important she felt it was to support Black literature and Black people, all the writers she loved and how wonderful their art was. I hear echoes of this when J.K. Rowling talks about the charming transsexual she met.

A big part of racism, like transphobia, is the refusal to see certain people as human to the same degree you see yourself as human. They are talked about, but not listened to. I’ve written over and over and over for the last few years about the staggering fact that when critics of “social justice” and “identity politics” write about these things, they don’t seem to take the time to read a single book by the people about whom they have such strong opinions. Renni Eddo-Lodge’s Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race is a superbly-written statement of the anti-racist case by a Black British woman, yet hardly any of the people who I see ranting about Identity Politics have ever picked it up and paid attention to its arguments.) Likewise, Serano’s Whipping Girl is a classic and highly readable transfeminist manifesto but I do not see it engaged with by those who have opinions on the equal rights of trans people. When Wynn patiently explained to Ben Shapiro what he didn’t understand about gender pronouns, did Shapiro apologize? Did he try to debate her or respond? Did he even acknowledge her existence whatsoever? (Hell, he’s even acknowledged my existence, and I’m far less famous than Wynn.) I think constantly of the devastating opening passage of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man:

I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination—indeed, everything and anything except me.

Transphobia and racism operate differently, but the marginalized always get shunted to, well, the margins. Writers like Serano, Jones, Montgomerie, and O’Leary have minuscule platforms compared to Rowling. In 2018, The Atlantic published a massive cover-story raising Concerns about transgender minors, presenting stories that could make transitioning seem dysfunctional and risky rather than a representative set of perspectives. Those who consider themselves Enlightened sympathizers to the rights of gender and sexual minorities can end up saying the most horribly dehumanizing and insulting things, and it’s extremely easy not to notice your blind spot when the people with the loudest voices all share it. The seeming “reasonableness” of Rowling’s patently unreasonable essay is a sad demonstration of just how far transgender people still are from winning the fight for social recognition.

III.

Having gone through the business of dissecting Rowling’s prejudices, let us return to the Wizarding World of Harry Potter. Once you understand just how irrational and hidebound Rowling’s thinking has been on the subject of gender, you may start to look at the Harry Potter books slightly differently. It is not just that you must now try to love the books while forgetting the author. Even within the books, certain things seem a bit strange.

For one thing, I hadn’t noticed until I went back to the books that Harry, Ron, and Hermione all become cops after leaving Hogwarts, joining the Department of Magical Law Enforcement. This involves, as far as one can tell, sending captive wizards to the prison of Azkaban, a place so bleak that many sentenced to it die of despair. Azkaban has long been guarded by Dementors, monstrous ghosts who drain people’s happiness and force them to relive their most traumatizing memories. At Azkaban this causes insanity (“Most go mad within weeks,” says Remus Lupin), though crimes as petty as “being an unregistered Animagus” are punishable with prison sentences. Thus torture for petty crime is accepted as routine in the wizarding world. A level of “Azkaban reform” evidently takes place during H-R-H’s tenure in the wizarding police, with dementors replaced with Aurors (wizard cops, like Harry and Ron). But Rowling also said of Azkaban’s island “those who entered to investigate refused afterwards to talk of what they had found inside, but the least frightening part of it was that the place was infested with dementors.” If the dementors are the least frightening part, what on earth have Harry, Ron, and Hermione chosen to spend their life doing? We do not find out much, but it is curious that instead of becoming professors, pro Quidditch players, newspaper editors, or apothecaries, our heroes all go into the law enforcement bureaucracy.

I am being somewhat facetious here. There is another aspect of the books that is more straightforwardly objectionable in a way that is actually important. I refer to Rowling’s treatment of slavery.

The wizarding world is served by an underclass of slaves called house elves, unpaid laborers who must strictly obey their “masters” and must punish themselves physically if they defy orders. It operates exactly like slavery: elves are property passed down with estates, and can only be freed by their masters. The Harry Potter Wiki says the elves “have no rights of their own and are viewed as servants without feeling or emotions,” yet Hogwarts itself under Dumbledore has a small army of them (H-R-H did not discover the elves’ existence until their fourth year of school, because they are kept out of view of the students). Kreacher, the house-elf Harry inherits from his uncle Sirius, uses the word “enslaved” to describe his condition, though Harry never frees his enslaved elf and as far as we can tell is still served by him at the end of the series.

Now, you may think I am unfairly applying real-world morality to a fantasy story here in presenting the house-elf system as a very brutal form of slavery. But Hermione Granger, encountering the elves, has exactly the same reaction.

“It’s slavery, that’s what it is!… Why doesn’t anyone do something about it?”

Hermione—who grew up in the ordinary, non-magical world—-is horrified by the fact that the wizards’ dirty work is done by slaves. She has the correct and expected moral reaction of a person from the contemporary world who enters a magical school only to find out it was built atop forced labor. Now, I’m very glad Rowling had Hermione react like this, because it should be a moment where the whole wizarding world is revealed to be much less obviously “good” than it seemed when Harry was excitedly riding the Hogwarts Express and eating Bertie Botts’ Beans. Hermione’s discovery of the slavery upon which Hogwarts functions, with the gentle Dumbledore apparently approving of it and hiding it, should have been a revelation that shook H-R-H to their core, and created a moral conflict central to the story.

That’s not what happens. Everyone except Hermione greets the slavery revelation with a resounding “Eh.” Hermione cannot believe this. She thinks she is going crazy. Her friends are good people, so how can they not see what an injustice is being done? She founds a group called the Society for the Promotion of Elfish Welfare. Nobody, not even the kindliest characters, is interested in joining. Ron laughs at it, refers to it as “Spew.” Hagrid says the elves enjoy their work. Hermione’s efforts to get anyone to care are completely futile.

But what’s disturbing is that Rowling seems to agree with the wizards that the slavery doesn’t matter very much. The house elves are portrayed as happy slaves who live to work. They rebuff Hermione’s attempts to free them. I quote again from the Harry Potter Wiki:

Despite the seemingly horrid lifestyle that house-elves endure, house-elves seem to actually enjoy being enslaved… house-elves will feel insulted if their master attempts to pay them, give them pensions, or reward their service with anything except kindness.

Hermione is portrayed in the books as a well-meaning but naive activist who “hurts the very ones she is trying to help,” and who simply doesn’t understand what she is meddling with. In fact, when a house elf is freed, it is seen as potentially disastrous; an elf called Winky slips into depression and alcoholism after leaving her master’s service.

One might try to excuse extremely fucked-up things as part of the “logic of a fantasy world,” but Rowling is straightforward: this is slavery, but the slaves enjoy being enslaved and resent efforts to free them. It’s concerning that Rowling shows children this scenario because the “happy slave” is a common illusion. Frederick Douglass writes in his memoir about how white people always assumed that slaves were content because they heard them singing and saw them dancing. But, he says, their songs were of sorrow, as anyone who listened closely would have realized. James Weldon Johnson writes of a Black friend whose white wife, a Louisiana native, told him she never realized “colored people” had any problems until he had told her. “They always seemed so happy!” she said. Richard Wright, in Black Boy, writes about the ways that under Jim Crow, Black people were forced to put on smiles and pretend to enjoy their oppression, lest they incur the wrath of white people.

I generally hesitate to say what J.K. Rowling “should have done,” because as I’ve mentioned, I am not a talented writer of children’s literary fiction. But here I think it is quite obvious what she should have done: she should have revealed that the house-elves’ supposed “enjoyment” of their servitude was false, that (as actually happens), they feigned enjoyment because they knew their masters did not want to think of themselves as cruel people. Rowling was right to show Hermione being rebuffed and treated as naive. But it is bizarre that she implies this because her slave-class was actually content, instead of simply mistrusting Hermione and fearing her intervention would make the situation worse. Books 5, 6, and 7 should have involved Hermione getting the elves to trust her to the point where they could admit their real feelings, and the wizards being surprised to find out that their elves have always despised them, and having to reckon with the fact that the “good-evil” distinction between themselves and Voldemort is not so obvious, because they themselves are oppressors. Instead, SPEW was simply dropped (though later in life Hermione apparently did work on house-elf labor condition regulations at the Ministry of Magic). Rowling said explicitly that she wanted Harry “to leave our world and find exactly the same problems in the wizarding world” such as “the intent to impose a hierarchy” and “this notion of purity,” but the problems are the existence of Bad Wizards with Nazi inclinations, not so much any deep flaws within the supposed Good Wizards.

I think there is real reason to be concerned about the way Rowling treats slavery, given that hundreds of millions of children have read these books during formative years of their lives, and plenty of people have drawn direct political inspiration from the books. I am certain that many fans get the impression that Hermione’s experience teaches a lesson. I quote from a fan’s essay on why Hermione was wrong:

If Hermione did her research well she would have easily realised that the majority of house elves are happy and that S.P.E.W would have offended them…. If I was Hermione when she was promoting this organisation for protecting house-elves, I would have focused more on stopping house-elf abuse, not attempting to free them.

A Potter fan on why Harry didn’t free his enslaved elf:

I know it is counter-intuitive but freedom is lethal for house elves. It is similar to how freeing caged birds is actually an inhumane act… They are not used to living for themselves and hence have lost the ability to do so… Every attempt Hermione made to help them was met with anger and disgust…. Now, I am not saying that it is right to enslave house-elves. It is not. But it is also not easy to undo centuries of behavioral training that these elves have undergone and this is something Harry realizes.

The fan quotes Sirius Black saying that “we can’t set [Kreacher] free,” in part because “the shock would kill him.”

Yes, yes, it’s just a book. But as I look back on it now I am disturbed that fans of J.K. Rowling find themselves literally repeating as true arguments that have been used for centuries to defend oppressive hierarchies as being “good for” the oppressed.

In Rowling’s treatment of slavery in the wizarding world (again, the word is used in the books, I’m not being extreme here), we see the unmistakable signs of Rowling’s personal liberal politics. The lesson Hermione learns is the one liberals are always telling the left: don’t try to radically change the system, you will make yourself absurd and fail. Instead, work for moderate, sensible reforms, like improving working conditions for the enslaved.

An author with more political intelligence would have written this very differently, as a story of the way the enchanted world of kindly wizards turned out to be much more morally ambiguous than it initially seemed. Instead, we get something akin to the way centrist Democrats view the world: the bad fascists (the Dark Lord and his Death Eaters) must be stopped, but we are the good ones. Of course, when you look more closely, you realize that many of the Good Ones support maintaining a class system through force, but that’s easy to miss if you are solely focused on the Manichean struggle between darkness and light.

Rowling is not a U.S. Democrat of course. But liberal Britain has its own buried sins. To me, Harry Potter always gives off a mild whiff of P.G. Wodehouse, with its funny aristocratic names, its manors and castles, its “old school tie,” and much like Wodehouse, there’s a strange obliviousness to the exploitation that has enabled this kind of luxury to develop. The British private school is a place that manufactures the ruling elite, and as George Orwell documented, despite the romance of “school stories,” in reality these are often brutal places. The refined splendor of castles and manors can only be supported by a highly unequal social structure. Rowling is against explicit racism—Voldemort is intended as a Hitler obsessed with blood purity—but like many liberals she focuses on that which is quite obviously evil and ignores that which is less obviously so, but is in many ways equally pernicious. What “house elf slavery” is to the wizarding private school, colonialism was in building the real-world British equivalent, and as Sunny Singh notes, Harry Potter inhabits a “sort of fuzzy liberal Blairite… storyworld based on a British history without Empire and slavery.” (As we’ve seen, this is not quite accurate: there is slavery, it’s just that none of the characters care about it.)

R.J. Quinn, in Jacobin, writes of other ways in which the political orthodoxies of our time are woven into the Potterverse:

“Magic,” as it is discussed in the Harry Potter universe, is a force that allows its wielder to have a profound and measurable impact without organizing, sacrificing, or indeed doing much of anything. JK Rowling presents her reader a fantasy world in which “being really good at homework” makes you a literal superhero…. Rowling’s neoliberal magic world is not a dark and dangerous place, but a comfortable retreat, where long-held myths—meritocracy, the assured benefits of elite education, the decisive power of facts and rightness—are not myths at all, but the very organizing forces of reality itself. In the world of Harry Potter, there is a linear relationship between how much of a nerd you are and how much real, worldly power you have.

Now here I think the gentleman doth grumble too much. This is not strictly accurate: Rowling’s world is very dangerous, people die there all the time, and Harry’s success comes from his character rather than his being “good at homework.” I do not think it is, strictly speaking, a tribute to nerds, and I do not think we need to sniff out the neoliberalism in every passage of fantasy fiction. But I do think we can criticize the books’ politics, because there are explicitly political storylines (the capture of a bureaucracy by a totalitarian racist, an activist campaign over working conditions, the highest aspiration of the main characters being to join the Department of Law Enforcement and throw bad guys in the torture-prison). And it’s true that the political messages Rowling puts in the books are, interpreted most generously, not very challenging to conventional wisdom (“the values of a nostalgic, conservative Little Britain,” one Guardian writer concluded). Even though Hermione knows the house-elves are enslaved, and believes in their freedom, SPEW’s highest aim is to “get an elf into the Department for the Regulation and Control of Magical Creatures, because they’re shockingly under-represented,” admittedly a bit of a neoliberal ambition. Rowling did not even have the courage to make Albus Dumbledore’s homosexuality explicit, preferring to retcon it in after the fact. Laurie Charles writes critically of Rowling’s habit of “shoehorning diversity into the canon and pretending it was always there.” I do not agree with Quinn’s implication that Harry Potter needed to be a socialist realist work in which Harry learns that the real magic comes from labor organizing, but Quinn is at least right that Rowling puts nothing in the books that could lead her readers to question the legitimacy of exclusive private school meritocracy and hierarchical social structures.

In discussing Rowling’s politics, I am not simply speculating or extrapolating from the text of the Harry Potter stories. She’s been very vocal about political issues on Twitter, and during Jeremy Corbyn’s tenure as Labour Leader, she was vocally hostile to having a radical socialist in charge of the party, saying that he was helping the Tories, destroying the Labour Party, and in fact that “Corbyn and his comrades will be delighted” if “Labour is decimated.” Because Corbyn is a kindly old man with a faint air of spaciness, some young lefties began referring to him as “Dumbledore.” This incensed Rowling and she swiftly poured cold water on it, using her authorial privilege to declare officially that Corbyn was not Dumbldore.

In her hostility toward Corbyn, Rowling displayed the same lack of curiosity and empathy that has so exasperated her trans critics. My friend Gautham Bhatia, in a beautiful essay for this magazine, writes of what Corbyn meant to him as a resident of Britain coming from a post-colonial country. Bhatia writes that Corbyn was different from every other British leader of his lifetime in seeming to care about the impact that British policies had on people who were not white:

[Corbyn] was an internationalist. He had spent his political life in solidarity with struggles for equality and justice all over the world. Often, these struggles had brought him into direct conflict with “Western” foreign policy—and therefore, by extension, against “the West.” And so—whether it was Libya or Ireland—he often stood alone in support of a cause, in the teeth of intense hostility. It must have been a lonely and dispiriting exercise. But if—as Thomas Geogheghan writes—“solidarity is the only love left in this country that dares not speak its name”—then gosh, did Jeremy speak it! How do you describe that feeling of finding, for the first time in your life, a politician who speaks—honestly and clearly—the convictions that you have always felt, and which you had resigned to never hearing articulated?

This internationalism was rare and it was valuable, and it would have meant that a Corbyn government could have pursued a more humane and just foreign policy than Labour had previously (New Labour, after all, plunged Britain into the criminal war in Iraq). It is sad that Rowling couldn’t see the importance of that.

Her comments on the Labour Party and attacks on its leadership may have done serious political damage: the 2017 British election was incredibly close, with Corbyn just a few thousand votes away from becoming Prime Minister. If only Rowling, supposedly a proud Labour supporter, had not spent month upon month trashing Corbyn, but had instead given his politics a chance, and had exhorted her 14 million followers to get involved in campaigning for the truly admirable slate of policies in the party manifesto. It is quite possible that we would not have had the conniving sociopath Boris Johnson come to power, nor had his disastrous coronavirus response.

Some of my fellow leftists groan about people who see politics through the lens of Harry Potter, although personally I think it’s rather charming that some members of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau see themselves as a kind of Dumbledore’s Army. I see little inherently wrong with using children’s literature as a reference point for understanding real things, whether Aesop’s Fables or Harry Potter. The problem is that while Rowling can imagine 50 different kinds of magical root for Professor Sprout’s Herbology course, she can’t imagine her way past myopic middle-class British values. This is a shame not just because it hurt the series as literature (the books would have been better with an actual plot about Dumbledore’s homosexuality, or an actual effort to expose the normalization of slavery in the wizarding world). It also means that many of us, as we grow up, have to leave these books behind, because to dwell too long in this world stunts our moral growth. As Laurie Charles comments:

Nobody deserves to have their childhood mythology stripped of its moral architecture in such a degrading way as our generation’s: the same author whose books taught us the meaning of courage and tolerance is now publicly behaving in patterns of cowardice and bigotry.

It is a genuine tragedy, because the Potter books are so rich, and could have been—should have been—truly inspiring pieces of literature. I still think, and will always think, that these books are a dazzling feat of human inventiveness. J.K. Rowling can imagine almost anything. She can imagine fantastic beasts, enchanted castles, oozing potions, explosive spells. But she cannot imagine her way to questioning the deepest injustices of our time, and she cannot imagine why people are offended when she says hurtful and ignorant things about marginalized people.

Many of the themes in this article are also discussed on the “Wizard Children” episode of the Current Affairs podcast.

Correction: This article originally stated that a controversial paper was written by “Leah Littman.” The paper was written by Lisa Littman. Leah Litman is a law professor who has been a guest on the Current Affairs podcast and whose name got mixed up in my mind. I apologize to Prof. Litman and regret the error.

Update: This article includes a block quote from Huck magazine. The quote included a sentence about Maya Forstater that has since been removed from the article being quoted. We have updated the quote to reflect the updated article.