How To Pretend That You Are Smart

There is a difference between assertion and argument, but a lot of highly credentialed people do not notice when they’re just stating their prejudices rather than proving anything.

[content warning: racism]

Today we are going to look at two examples of men with PhDs from Harvard making asses of themselves without realizing it. We are going to see how things that are wrong, unproven, nonsensical, or bigoted are presented as insight, and Very Smart Men are often not actually very smart at all. That will probably not come as a surprise to you, but what I want to demonstrate here is how easy it is to disguise one’s unfounded opinions or prejudices as scholarly musings.

The two exhibits I have brought for today’s show-and-tell are “Cultural Difference” by Lawrence M. Mead, published in the social science journal Society, and “The Four Quadrants of Conformism” by Paul Graham. You may not have heard of these men, but they are prominent in their respective fields. Mead is an NYU politics professor credited as one of the “intellectual godfathers” of the “welfare to work” idea that Bill Clinton made law in the 1990s. Graham is a Silicon Valley startup guru and venture capitalist who has helped to “incubate” such companies as Dropbox, Reddit, and Airbnb, and has become controversial for his statements defending inequality and disparaging labor unions. (He is also the subject of the poem “Paul Graham Is Asking To Be Eaten” by sociologist Holly Wood.) I think it is useful to look at them both, even though they are quite different pieces of writing (one is a piece of racist trash, the other is just a piece of trash), because they both illustrate how confident credentialed people treat “saying things you believe” as synonymous with “proving those things to be true.”

They also are both good examples of a kind of fake social science, whereby you simply make unsubstantiated observations about human beings that confirm things people already believe, and the reader’s pre-existing feelings (their pre-judgments or “prejudices” if you will) are doing the work that evidence should be doing. I would argue that this kind of writing is extremely common and that we need to watch out for it because, if we share the prejudices of the author, we will end up believing things that may be totally untrue, and we will think we have read a good argument when we have in fact just been told that we were right all along.

Let us begin with Graham. Graham’s essay “The Four Quadrants of Conformism” is a defense of free speech against “conformists” who are stifling it.

Graham begins by arguing that there are four types of people in the world: “aggressively conventional-minded, passively conventional-minded, passively independent-minded, and aggressively independent-minded.” By this he means: there are those who are sticklers for the Rules and aggressively enforce them, those who follow the rules obediently but are not noisy about them, those who do not follow the rules but aren’t confrontational and those who do not follow the rules and aggressively challenge authority. He calls them, based on types of children one sees in a schoolyard, “tattletales,” “sheep,” “dreamy ones,” and “naughty ones,” respectively. Graham says that the four types are found across “most societies,” that what people are depends “more on their own personality than the beliefs present in their society,” and that “like four species of birds” they have “distinctive calls”:

- The call of the aggressively conventional-minded is “Crush <outgroup>!” (It’s rather alarming to see an exclamation point after a variable, but that’s the whole problem with the aggressively conventional-minded.)

- The call of the passively conventional-minded is “What will the neighbors think?”

- The call of the passively independent-minded is “To each his own.”

- And the call of the aggressively independent-minded is “Eppur si muove.“

Graham says that the plurality of people are the sheep, and that the “aggressively independent-minded” are the rare ones (of course, he says startup CEOs fall into this category). The “aggressively conventional-minded” are “responsible for a disproportionate amount of trouble in the world” and “a lot of the customs we’ve evolved since the Enlightenment have been designed to protect the rest of us from them.” Societies, he says, prosper “to the extent they have customs for keeping the conventional-minded at bay.” This is where he gets to free speech, or “freely debating all sorts of different ideas, even ones that are currently considered unacceptable, without any punishment for those who try them out to see if they work.”

Graham then argues that the conventional-minded are currently actively “shut[ing] down” free inquiry:

In the last few years, many of us have noticed that the customs protecting free inquiry have been weakened. Some say we’re overreacting — that they haven’t been weakened very much, or that they’ve been weakened in the service of a greater good. The latter I’ll dispose of immediately. When the conventional-minded get the upper hand, they always say it’s in the service of a greater good. It just happens to be a different, incompatible greater good each time. As for the former worry, that the independent-minded are being oversensitive, and that free inquiry hasn’t been shut down that much, you can’t judge that unless you are yourself independent-minded. You can’t know how much of the space of ideas is being lopped off unless you have them, and only the independent-minded have the ones at the edges. Precisely because of this, they tend to be very sensitive to changes in how freely one can explore ideas. They’re the canaries in this coalmine. The conventional-minded say, as they always do, that they don’t want to shut down the discussion of all ideas, just the bad ones. You’d think it would be obvious just from that sentence what a dangerous game they’re playing. But I’ll spell it out. There are two reasons why we need to be able to discuss even “bad” ideas.

The two reasons are (1) the standard John Stuart Mill argument that the only way to know you are right is to allow free and open questioning and (2) that “ideas are more closely related than they look” meaning that “if you restrict the discussion of some topics” then “the restrictions propagate back into any topic that yields implications in the forbidden ones.” Graham says that while universities used to be a sanctum for free debate, this is no longer the case:

In the past, the way the independent-minded protected themselves was to congregate in a handful of places — first in courts, and later in universities — where they could to some extent make their own rules. Places where people work with ideas tend to have customs protecting free inquiry, for the same reason wafer fabs have powerful air filters, or recording studios good sound insulation. For the last couple centuries at least, when the aggressively conventional-minded were on the rampage for whatever reason, universities were the safest places to be. That may not work this time though, due to the unfortunate fact that the latest wave of intolerance began in universities. It began in the mid 1980s, and by 2000 seemed to have died down, but it has recently flared up again with the arrival of social media. This seems, unfortunately, to have been an own goal by Silicon Valley. Though the people who run Silicon Valley are almost all independent-minded, they’ve handed the aggressively conventional-minded a tool such as they could only have dreamed of. On the other hand, perhaps the decline in the spirit of free inquiry within universities is as much the symptom of the departure of the independent-minded as the cause. People who would have become professors 50 years ago have other options now. Now they can become quants or start startups. You have to be independent-minded to succeed at either of those. If these people had been professors, they’d have put up a stiffer resistance on behalf of academic freedom. So perhaps the picture of the independent-minded fleeing declining universities is too gloomy. Perhaps the universities are declining because so many have already left.

So concludes Graham’s theory. As with most clever works of sophistry, it begins with things that are obvious, so as to seem reasonable, before sliding into claims that are highly contestable. So, yes, we know that people tend to follow social rules, see the Milgram experiment (and of course, every atrocity in history that has been tolerated by a passive majority). Graham’s own classifications and descriptions, however, are more dubious.He says that aggressive conformism is driven by a desire to “crush” an “outgroup.” Is that true? Do most societies really break down on these lines or is it something he just thinks? I have no idea, because here’s an important point about Graham’s theory: other than mentioning schoolchildren, he includes no examples or citations. (Generally when you hear people talking about “ingroups” and “outgroups,” your social scientific bullshit detector should start buzzing, because this can be used to suggest that people who criticize any group, such as rich people who do not pay their taxes, are simply “loyal to their political tribe” and irrationally resentful of the “outgroup.”)

So the social psychology of the piece is all unproven. But so is the free speech stuff: has there in fact been a narrowing of the ability to discuss ideas, or is there simply a perception that this has happened by people who use anecdotes as their data? Is there a recent trend toward greater restriction or has there always been the “manufacturing of consent”? Perhaps there is actually more lively debate now, on a broader range of topics, than ever before. (I see nearly everything imaginable being debated on social media.) Are the people who run Silicon Valley “independent-minded” or are they actually aggressively committed to preserving the existing economic status quo? Is it people like Graham who have less free speech or is it people whose politics threaten the interests of the wealthy and powerful? Did the “independent-minded” really used to take refuge in the “courts”? (What does this even mean? That judges used to care less about enforcing rules? They don’t care about rules now.) Do you really have to be “independent minded” to be a “quant” or do you just have to be good at math even if you are, say, an aggressive promoter of U.S. imperialism who applies their quantitative skills to helping the country build bigger and better death robots? Every single thing Graham says is completely unsubstantiated and vague, but he is speaking to people in Silicon Valley who think of themselves as smart and independent, and so perhaps doesn’t feel as if he has to back up his assertions about the smartness and independence of Silicon Valley types.

It’s hard to know what Graham is even talking about most of the time. What ideas does he think are not being debated? What restrictions have been put in place? What are some examples of things that are being affected by the inability to pursue certain lines of thinking? Which norms have eroded and in which institutions and to what degree and what consequences are imposed for Thinking The Forbidden Thoughts? How are we to evaluate whether there has been a loss to intellectual discourse without understanding what has been lost? Incredibly, Graham says that he had nine people review and give comments on his essay before he published it, including Yale sociologist Nicholas Christakis. Apparently not one of those people asked Graham “What the hell are you talking about? What is this referring to? Could you please buttress this with some examples?” This tells us a lot about the kind of bubble Graham must live in. (Warning to rich people: if you show your very bad piece of writing to lots of people and they tell you it is very good, remember that they have an incentive to flatter you and not point out your deficiencies, partly because you have the power to bestow favors upon them, and partly because they will assume that you must be smart if you’re rich and that if they don’t understand it’s surely just a sign of your superior genius.)

Graham’s actual reasoning is also very poor. For instance, he says that he will “dispose immediately” of the argument that limitations on free discussion are for a greater good. The way he “disposes of” this is by saying that when the “conventional-minded” get the upper hand, they always claim restrictions are for a greater good. How does this dispose of the argument? First, he has offered no proof that only the “conventional-minded” believe that certain topics should not be debated. I am quite independent-minded but I might be open to the position that not everything that is legally allowed to be discussed should be the subject of ongoing public debate (for instance, the question of whether slavery should be brought back), although Graham has defined his terms so that being open to seemingly any norms about the proper sphere of debate automatically makes you conventional-minded. This is why he is able to “dispose of it immediately”: because if you are on one side of the argument, he has already decided that you are conventional-minded and can be dismissed. Thus Graham does not actually need to evaluate the substantive question of whether or not the “greater good” is in fact being served. Anyone who says the greater good is being served is conventional-minded. You “cannot judge” unless you are “independent-minded,” so if you disagree with him you have only proved that you are a sheep. Case closed. (“You would always say this even if it were not true, therefore it is not true” is, by the way, fallacious. Ironically, Graham is known for once having created a little pyramidal diagram showing people how to produce more rational arguments.)

Paul Graham is a computer scientist, which theoretically involves having a good understanding of logic, and yet is capable of making arguments like: “When you accuse Silicon Valley of x, you’re implicitly saying x works well, which doesn’t seem smart if you’re against x.” That might make you go “Huh?” and it should. Graham seems to mean something like: if you are criticize Silicon Valley for some tendency it has, because Silicon Valley is successful, you are implicitly conceding that successful organizations have this tendency, therefore you are saying that a thing successful organizations do is bad, which is dumb. Now, you have probably noticed the flaw, which is using the term “works well” to cover both “is a feature of companies successful in a capitalist economy” and “is a good thing for humanity.” If I criticize, say, Airbnb for failing to ensure Black people have the equal ability to rent accommodations, or Uber for exploiting its drivers and crushing their attempts to improve the terms under which they work, I might indeed “implicitly” be saying that these practices work well for the owners of Uber and Airbnb, but I do not care what works for the owners of Uber and Airbnb. My guess is that Graham’s belief that his sentence is logical comes from his inability to conceive of value in any terms other than “market value.” To a normal human, it seems ludicrous to say that criticizing Silicon Valley is always “not smart” because you’re criticizing something that has been successful. But the rich are not normal humans. They are not held to the same standards of intellectual rigor as everyone else, because their wealth is assumed to be proof of their brains. (See Elon Musk: a portion of the public will never be persuaded that Musk is not a genius, no matter how many dumb and wrong statements he makes.)

Let us now turn to Lawrence Mead’s essay, which is much worse.

Mead attracted negative attention for an article he has just published in Society called “Poverty and Culture,” which argues that “attempts to attribute longterm poverty to social barriers, such as racial discrimination or lack of jobs, have failed” and the real reason for American poverty is that “racial minorities… all come from non-Western cultures where most people seek to adjust to outside conditions rather than seeking change” and “minorities—especially blacks and Hispanics—typically respond only weakly to chances to get ahead through education and work.” Now, this is from the abstract, and much as I would like to go through this article and examine how Mead supports his claims, thanks to the absurdity of academic publishing, it costs $39.95 to download the article. I am not going to pay that. Fortunately, Mead has been arguing this same thesis for several years in other articles, so I will go through one that looks as if it is almost exactly identical, called “Cultural Difference,” published two years ago in Society, and adapted from his 2019 book Burdens of Freedom: Cultural Difference and American Power, which I was able to obtain for free.

“Cultural Difference” is seven pages long, and its thesis is that the “culture” of “minorities, immigrants, and poor countries” is responsible for their relative lack of wealth. Let me give you a taste. Be warned: it’s extremely racist! (After you begin to get the idea, you might want to skip the rest.)

The United States is the world’s most individualist country, where most people approach life as a quest to achieve their personal goals. But most minority Americans and recent immigrants tend to adjust to the world as it is rather than seeking change.

… The most intractable issue in American politics has long been race. But we fail to understand it because the sameness assumption treats blacks as culturally no different from other people. No allowance is made for the fact that most blacks came from Africa, the most collective of all cultures, and then endured slavery and Jim Crow. So most of the group today has a relatively passive temperament compared to other groups. Most blacks still focus on immediate adjustment and not on long-term achievement. Blacks also suffer worse social problems, such as crime and unwed pregnancy, because historically they depended more on external authority to keep order, which is the non-Western manner. A free society lacks most of that structure. It assumes that people can keep themselves on the rails mostly without oversight, and that is not the style blacks brought to America. … If noticed at all, the relatively passive disposition of blacks is blamed entirely on the adversities they have suffered within America. Had they been more fairly treated, we assume, they would be more assertive. But if that were true, black social problems should have been worst under Jim Crow, then declined once the group gained equal rights in the 1960s. In fact, exactly the opposite happened. The decline of poor black society occurs largely after civil rights rather than before. The dismantling of Jim Crow social controls left the group unable to maintain its families and neighborhoods. Order has somewhat improved only since society recently tightened up on welfare and law enforcement. For a non-individualist culture, freedom is a greater threat than oppression… By and large, successful blacks are those who have abandoned the traditional black mindset and instead become individualist… Martin Luther King, Jr., led the fight for civil rights, yet he also said that, to seize their new opportunities, blacks themselves would have to display “assertive selfhood.”[2] To do that is a big change from the original culture of black America.… Of course, whether equal opportunity for minorities is achieved is still disputed, but neither side in that battle admits cultural difference as it should. Those who believe discrimination still exists assume blacks are already individualists who need only a fairer society to get ahead. That fails to credit the defeatism of many lower-income blacks, which undercuts efforts to help them. On the other side are moralists who reprove blacks for failing to assume responsibility for their own problems. But individual responsibility is a Western idea. It cannot become relevant to most blacks until more of the group becomes individualist. Both sides assume a sameness that is lacking.… Nobody is responsible for the black predicament at an individual level, neither whites nor blacks. It results simply from cultural conflict. Blacks’ main problem is no longer that they face discrimination but that society assumes an individualist style that is not native to the group. The black middle class shows that blacks can indeed make it, but first they have to become individualist, a burden than only nonwhites face.

In his book, Mead actually goes further and says that “blacks, like other non-Western groups, had depended heavily on external authority to keep social order. Jim Crow, however unjust, did provide that. But when poor Southern blacks moved to Northern cities, they lost that structure.”

Now, you may think to yourself “this sounds like it came straight out of The Daily Stormer.” And you would be right. In fact, this would have been considered racist even 50 years ago, back when America was even more racist than it is now. The infamous Moynihan Report on the pathologies of “The Negro Family” did not go as far as Mead, but when it was released in 1965, it pissed off civil rights leaders so much that the Johnson administration had to distance themselves from it.

And yet Mead is not on the fringes of American intellectual life. He holds a tenured professorship at NYU. His work has been published by the Brookings Institution and Princeton University Press. He has written for U.S. News & World Report, testified before Congress, consulted for federal, state, and local government agencies, been honored by the National Academy of Public Administration, and appeared numerous times on CSPAN.

Mead’s racist turn is not new, either. In his 1992 book The New Politics of Poverty, Mead argued that “if poor blacks functioned better, whites would show less resistance to living among them,” arguing that ending residential and educational segregation was “infinitely” less important than “functioning parents” and that “black communities lack resources today mainly because so few lower-income blacks work steadily…” But even though Mead has long been very obviously a white supremacist who thinks the “traditional black mindset” is responsible for Black poverty and white culture is responsible for white success, he has managed to maintain connections to respectable mainstream institutions including one of the most prestigious universities in the world.

The article is, of course, jaw-droppingly offensive. I can’t get over how appalling it is. He says that freedom is actually worse than oppression and that Jim Crow successfully created “social order” (there was no “social order” under Jim Crow, it was a regime of racial terrorism that lynched human beings for imaginary offenses. This is genocidal insanity, not “order.”) He reduces every racial inequality to “simply” a result of “cultural conflict.”

We can and should dismiss Mead’s racist article out of hand. NYU should not be employing this man. I do not think there is any serious need to respond to his arguments, which are about at the level of a 1950s pamphlet by the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

But it is also important to note that there aren’t any actual arguments in this article. One of the most remarkable aspects of Mead’s piece article is how completely lazy it is. Mead cites almost no sources to back up any of his claims. Over the entire passage explaining his theory of Black mindsets, Mead has exactly one footnote: the phrase from Martin Luther King is taken from a 2009 article in the New York Times Magazine. This means that everything he says is bare assertion, meaning that he’s not proving it, he’s just saying it.

One thing right-wingers often say about the left is that while we denounce things as racist, we do not deal with the actual case being made. Why, they say, do you simply say that this is bigoted, rather than showing that my case does not succeed? And I do think it is worth showing why we tend to wave stuff like this away: not just because it conflicts with our anti-racist values, but because it is utterly worthless as social science. Like the work of Charles Murray (whom Mead, of course, cites favorably), it is fake scholarship. It’s just this guy’s prejudices and emotions thinly disguised as academic research.

Consider what he says about the causes of poverty:

The long-term poor, however, are mostly black and Hispanic, and these groups have proven much less responsive to opportunity. Despite their low income, poor adults seldom work regularly, and they also suffer high crime, school failure, and disordered family lives, with parents usually splitting up or never marrying at all. A frequent reason is that fathers fail to work regularly and mothers give up on them. Experts assume that the poor, like blacks, are optimizers like the middle class, but fifty years after civil rights, that is no longer plausible. For decades the convention has been to blame nonwork and the other problems entirely on various inequities and “barriers” in the larger society. It has been taboo to cite the lifestyle of the poor themselves. Scholars spend their careers striving to find some new barrier. Recent research, for instance, stresses the damage done to early child development by low income. But no social cause explains well why poor adults so seldom work regularly. (Once again there are no citations to any research in this passage, even when Mead mentions “recent research.”)

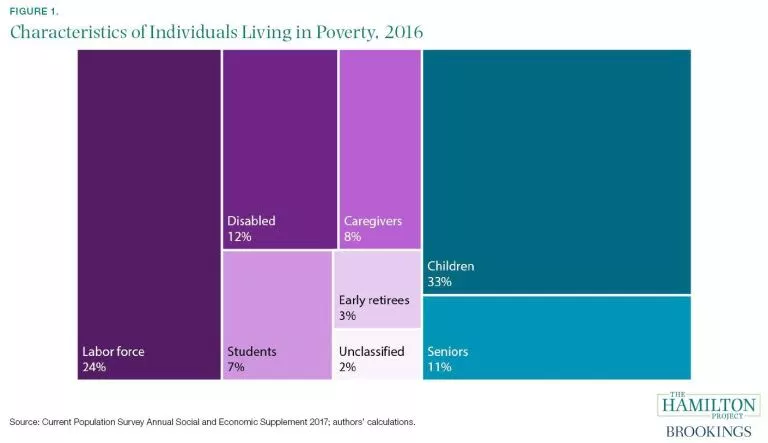

Mead has long been known for pushing the idea that there are plenty of jobs available, but that poor people simply refuse to work because of their attitudes, which is why his central policy idea was imposing work requirements for welfare benefits. Now, if you know anything about who the poor actually tend to be, you realize instantly why statements about “the lifestyle of the poor” causing poverty are absurd. Here’s some actual information:

As you can see, the majority of the poor are children, disabled people, old people, students, and caregivers. Matt Bruenig calculates that when you add to this those who already have full-time work and are poor, that covers 90% of those in poverty. So the poor are either people who can’t/shouldn’t be working, or who are already working. Mead’s argument that the poor are poor because they are work-shy, is divorced entirely from social reality, unless he makes clear that he means children aren’t doing enough child labor. Care-givers should also presumably leave those they care for to die instead of performing full-time unpaid work taking care of them.

We can see, then, that what Mead is doing is not actually scholarship, but storytelling. He is laying out what he believes the world to be like. Mead says things like “Western culture is moralistic. Most people internalize ideas of right and wrong as general principles that they expect themselves and others to observe.” What proof is there of this as a difference between Western and non-Western cultures? Mead cites none. When he says that “Africa” is “the most collective of all cultures” what the hell does he mean? Does he cite the work of a single anthropologist, economist, philosopher, sociologist, historian? No, of course not. He is thinking at the level of a child, whose entire understanding of the entire continent of Africa is that it is a place where there are “tribes.” (This is unfair to children, actually, many of whom are not yet racist.)

What is important to note is that racism isn’t just morally wrong. It’s also intellectually indefensible, and the people who offer racist stories about the world have no interest in actually examining it carefully. They are convinced that they know how things operate on the basis of hunches they have. So Mead, for instance, does not feel as if he has to reply to Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s work showing how government and banks prevented Black families from accumulating wealth in the form of houses that could be passed down intergenerationally. Mead believes that, without a single piece of data, he can simply assert that actually the problem is simply Black attitudes, drawn from “African” culture. (One side note here is that while Mead is clearly wrong in his generalizations about the “passive, collective” mindset and the “active, individualist” mindset, the premise of his work is that individualism is good and that therefore racial minorities need to embrace the cut-throat culture of the “West.” This actually involves a separate racist assumption, which is that it is non-white people who should adopt white culture rather than vice versa. Even if Mead’s gross generalizations about “collectivism” versus “individualism” were accurate, individualism needs to be justified, not just assumed to be superior because it is what white people do. Personally I think to the extent the United States is dominated by a culture of selfish individualism it is actually quite dysfunctional, and the task is not to force people to adopt those values so they can succeed, but to dismantle that value system.)

It would take me approximately 900 pages to disentangle every racist assumption and shoddy piece of reasoning in Mead’s brief article. There are about five problems built into every sentence. His whole theory breaks down immediately. Like many who talk about the “West” and “non-West,” Mead flounders when it comes to the economic success of China and the high incomes of Asian Americans, and has no idea how to fit Latin America into the West/non-West schema. Mexico, after all, is a majority-Catholic, Spanish-speaking country, yet racists need to find a way to portray Mexican immigrants as non-Western even though most are descended from a mixture of Europeans and indigeneous residents of the Western Hemisphere. All Mead can say is that “Mexicans and Central Americans… are much more tentative, poles apart from the confident temperament that formed America… with a ‘collective psyche… rooted in passivity and underachievement.’” Does he offer any proof? Of course not. He’s a racist. For racists, the only proof required is that the racist believes it.

I have placed these two essays together because in both, we see overconfident men passing off their gut feelings as scientific fact. Graham’s essay is on a very different subject than Mead’s, and is not saturated with outright racism. But it is similar in that its persuasive power rests on “asserting that things are true based on the fact that they seem true according to the author’s prejudices” rather than “proving things are true using factual support and careful reasoning.” I want to draw your attention to what is common between these two pieces of writing, because while most of us will probably wave away an essay like Mead’s, the actual reasoning in Graham’s is no better.

There is a principle in good writing: show, don’t tell. We have an internal slogan that we use a lot in editing Current Affairs articles: PWEB, which stands for Please With Examples Buttress. (It was originally Please Buttress With Examples, but was rearranged to create a more memorable and pronounceable acronym.) PWEB means: if you make some highly contestable assertion, you need to back it up. If you say, for example, that there has been an erosion of the ability of people to freely debate ideas, you need to prove that. If you say that “cultural attitudes” are the cause of a particular social inequality, especially when there is a vast scholarly literature showing other causal explanations, you need to offer more than just your general vague impressions of what people are like. You can’t just use confidence as a substitute for evidence.

Or rather, you can, which is the problem. The Graham-Mead style is present in newspapers, on television, and even in some academic journals. You will see it frequently in the columns of David Brooks and Thomas Friedman. The funny thing about it is that if these writers submitted their work as a freshman term paper, it would almost certainly get a C or below. The professor would angrily scribble: “PLEASE PROVIDE CITATIONS FOR YOUR CLAIMS” and “A LOT OF RESEARCH HAS BEEN DONE ON THIS—PLEASE GO BACK AND READ.” A lot of time in college is spent teaching students that they cannot simply expound their theories of the world without reference to any scholarly literature. But once you have your credentials, and have made your way into an intellectual sinecure, whether in academia, media, or as a rich guru whose opinions are valued because people think the rich are smart, you no longer need to follow the rules.

The lack of any standards is a serious problem, because it means that “all arguments are equal.” You can make an argument for anything. You cannot make an argument that is equally well-founded, but if nobody is holding arguments accountable for being well-founded, then the climate change denier and the climate scientist, since both wear ties and speak with certitude, both have equal credibility. The anti-racist, who cites data, and the racist, who cites the truth that comes from the gut, are both of them Pundits.

What we must do is be ruthlessly skeptical. It is important not to let overconfident jabberers get away with presenting themselves as sages, saviors, and scholars. They must be exposed. Scholarly journals that publish racist pseudoscience, thereby failing to meet the minimal standards we should expect of them, should be met with harsh public criticism (because free speech is good). We live in a culture where charlatans are treated as deep and serious thinkers, and we must use the right of “open debate” (which does, in fact, still exist) to ruthlessly criticize all that exists, being unafraid of conflict with the powers that be.