How Should Values Influence Social Science Research?

Examining the difficult relationship between “politics” and scholarship.

I recently wrote about an incident in which a data scientist, David Shor, allegedly lost his job for tweeting about the efficacy of violent versus nonviolent protests. I certainly don’t think anyone should be fired over that—and whether he was actually fired because of the tweet remains unclear—but I mentioned in a parenthetical that I did not think highly of the academic research on protests that Shor was citing. The research, by Princeton political scientist Omar Wasow, looks at the effects of different kinds of protests in the 1960s, and Wasow’s takeaway point is that if protesters want to achieve their political goals, they need to be nonviolent, because violence “tends to work against their cause and interests, and mobilizes or becomes fodder for the opposition to grow its coalition.” My critique was not that I disagreed with Wasow’s empirical findings, but that I felt his research frames the issues badly, resulting in misleading scholarship that obscures more than it illuminates. I said that I thought it was “bad.”

My critique of Wasow’s research received some very negative feedback. VICE columnist Zeeshan Aleem suggested that I was advocating a form of anti-intellectualism, and “left intellectual discourse is going to fail in a very, very serious way if it deems research as ‘bad’ because it opens up a line of inquiry that might not jell with perceived political priorities.” New York contributing writer Jesse Singal asked: “What the fuck is happening with Nathan Robinson and Current Affairs?” And Wasow himself forcefully defended his work, affirming Aleem’s suggestion that I reject results that do not conform to my political priorities, saying that I made errors in my analysis, that I “do not care about facts at all,” that I misstate Martin Luther King’s beliefs, and that ultimately to “folks like Robinson, Black people appear to be useful only inasmuch as they serve him well.”

These charges are very serious, and deserve a thoughtful reply. I also admit that I did something wrong here, which certainly predisposed Wasow to be angry with me. I should not have waved away his research so quickly and casually in the article. What I wanted to do was give a very brief explanation of why the criticisms of Shor were not simply censorious social justice warriors trying to shut down scholarship that contained a finding they didn’t like. Instead, there were reasons why some activists felt his work was frustratingly incomplete on its own, or that the presentation of this single study outside of other contextualizing information was unhelpful and counterproductive. But if I was going to indict Wasow’s research I should certainly have been more thorough. A scholar has the right to feel insulted when his years of careful empirical work are simply scoffed at in an aside.

I think there is an opportunity here to productively discuss some important questions around the purposes of social science research, and how moral and political values should or should not guide the search for scientific truth. Even if you are not interested in a dispute between me and a professor at Princeton over a paper in the American Political Science Review, there is a much deeper debate here over what kinds of questions are worth studying, how we frame these questions, and how our choice of the questions we ask about the world influences our ultimate perceptions.

* * * *

Let me try to explain the basics of why Omar Wasow is mad at me. Wasow is a highly qualified and skilled political scientist, whose paper “Agenda Seeding: How 1960s Black Protests Moved Elites, Public Opinion and Voting” seeks to answer the question: How do the subordinate few persuade the dominant many? His paper looks at the efficacy of protest tactics, how different types of activism produce different types of political results. His central conclusion focuses on “violent” versus “nonviolent” protest, and he finds:

Evaluating black-led protests between 1960 and 1972, I find nonviolent activism, particularly when met with state or vigilante repression, drove media coverage, framing, congressional speech, and public opinion on civil rights. Counties proximate to nonviolent protests saw presidential Democratic vote share increase 1.6–2.5 percent. Protester-initiated violence, by contrast, helped move news agendas, frames, elite discourse, and public concern toward “social control.” In 1968… I find violent protests likely caused a 1.5–7.9 percent shift among whites toward Republicans and tipped the election.

So: violence by protesters “tipped the [1968] election to Richard Nixon over Hubert Humphrey” and “protester-initiated violence contributed to outcomes directly in opposition to the policy preferences of the protesters.” This is for reasons that will not surprise you: news coverage of violent protests is negative, elites react badly, white people become terrified and want someone who will restore Law And Order, etc. By contrast, nonviolent protests produce more positive coverage, public sympathy, etc. and there are fewer panicky white people driven into the arms of the Republican Party.

Now, here is something that might make you wonder why Wasow and I could possibly end up disagreeing so much: I don’t dispute the empirical truth of this finding. My argument wasn’t that Wasow’s paper is poorly-researched or that its math doesn’t add up or that it fails to prove the cause-and-effect relationship between protests and election results. In fact, let’s assume for the entire purpose of the discussion that it’s all accurate. It makes sense to me. It’s certainly a new finding that the difference between violent and nonviolent protests may have been so consequential that it could have literally changed a presidential election result. But I think it’s relatively uncontroversial to think that the white majority reacts with hostility and anger to violent protests by people of color, and that they become less sympathetic to protesters and their authoritarian instincts come out. Violence begets violence.

Why, then, did anyone object to this? Why could stating it possibly be controversial? How could well-done empirical research showing it not be worth doing?

The argument I made, albeit quickly and too dismissively, was as follows: by looking the effect of riots in isolation, we place outsized causal responsibility for the outcome on some of the least well-off, most oppressed people, and present their choices as “the thing that caused” a bad political outcome, when in fact their choices were only a very small part of a gigantic tangled web of causes. And by choosing to zero in on the decisions made by rioters, without looking at the causes/logic behind those decisions, we end up overlooking parties that are far more responsible for the ultimate political outcome. The end result is a misleading picture of reality, in which a comparatively minor thing—protester violence—is given outsized importance, and more time is spent critiquing the protesters than the thing they are protesting against.

Let me break down a few of my specific critiques. Essentially, Wasow’s framing of the situation is that in the 1960s, protesters had a choice between violence and nonviolence, and if more of them had chosen nonviolence, their interests would have been better served. But there are a few problems with this.

Conceiving of protesters goals’ in terms of electing Democrats and then judging protests by whether or not they do, in fact, elect Democrats.

Wasow’s conclusion is that “tactics matter” for protesters seeking to “assert their interests,” and that while “an ‘eye for an eye’ in response to violent repression may be moral… this research suggests it may not be strategic.” From a rigorous application of several statistical techniques, he concludes that “in [the] counterfactual scenario [in which 1960s Black protest was strictly nonviolent], the United States would have elected Hubert Humphrey, lead author of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” He also says that “the ‘transformative egalitarian coalition’ identified by Rustin (1965), King and Smith (2005) and others was fragile but, in the absence of violent protests,would likely have won the presidential election of 1968.”

But should the success of Hubert H. Humphrey be the metric by which we define the success of a movement, or the “political consequences of violent protest”? And should we attribute the failure of Humphrey’s campaign primarily to the choices of protesters? I’d like you to take a look at three passages from the book An American Melodrama: The Presidential Campaign of 1968, a thorough 1969 book on the election. The first is a statement from a Humphrey campaign manager about the weak position the campaign was in after the disaster of the Chicago convention:

Here was our situation right after Chicago… We had no money. We had no organizations. We were fifteen points behind in the polls. We did have a media plan, but we didn’t have the money to go with it. And we were going to have to change our ad agency anyway. The worst thing was that we didn’t have enough time. The candidate approved the campaign plan in Chicago on August 30. That was the Friday before Labor Day, which is the day the campaign begins, traditionally,. Instead of having three or four weeks to mount a campaign, we had three days. And so the candidate went on the road, and he was a disaster.

The second is about the way Humphrey betrayed black voters by embracing segregationist governor Lester Maddox:

Nothing that Humphret did in 1967 caused more distress and anger among the liberals and the blacks than a picture that was taken of him arm-in-arm with Lester Maddox, the abusively segregationist Governor of Georgia. Apparently this came about not through cynical political contrivance but on a sheer impulse of Humphrey’s. The next morning his press secretary, Norman Sherman, pointed out what a disastrous reaction there would be.

“What are you talking about? I never did that. I was just polite to him, that’s all,” said Humphrey.

“Yes, you did, Mr. Vice-President.”

“No, damn it, I did not.”

Sherman said nothing, but placed the New York Times in front of Humphrey. There on page one was the picture of Humphrey with Maddox.

“Gee,” said Humphrey after a minute, “I guess I did, at that.”

The third is about how Humphrey, who Wasow describes mainly as “the lead author of the 1964 Civil Rights Act” had actually become a symbol of the conservative wing of the Democratic Party:

Yet by 1967 the arch-disarmer [Humphrey] had turned into an arch-apologist for the war, who was given to trotting around Vietnam looking more than a little silly in olive-drab fatigues and a forage cap. The man whose name had been a by-word in the South for softness toward Negroes had taken to lecturing black groups about how the Irish and the Jews and even the Cubans had made it in America without Federal grants, so why couldn’t they? The wild-eyed reformer had become the natural champion of every conservative element in the Democratic Party.

Humphrey’s friends and apologists argue that he was trapped by his position as Vice-President. This is untenable. For one thing, his dicta, particularly on the war, went far beyond what solidarity with an Administration or loyalty to a President demanded. Again and again Humphrey insisted that he believed in the war. One should do him the credit of believing him.

Surely we are beginning to see a problem with the framing of the research, then. It is the job of protesters to elect this man, and if their actions do not elect him, they are behaving in a counterproductive and irrational manner. By zeroing on the variable of “how much you helped Hubert Humphrey in 1968,” Wasow does what the Democratic Party is still doing today, namely treating “having more members of the blue team than the red team in power” as the measure of the success of progressive organizing, no matter how reactionary the particular “blue” officials we elect might be. Personally I do not think a scholar who is trying to be neutral should treat Hubert Humphrey as the ambassador for a “transformative egalitarian coalition.” Treating Johnson-Humphrey as the political friends of the disenfranchised is perverse, especially given Vietnam—which astonishingly goes unmentioned in a paper about the causes of 1968 political outcomes, perhaps because it severely damages the case that electing Democrats is good. We also see here a bit of reinforcement of the idea that the Democratic Party does not need to earn people’s votes, that Hubert Humphrey was worth supporting even if he was chums with Lester Maddox because he was the “lesser evil.”

The narrow focus on the election of Humphrey also means not looking at other potential consequences of violent and nonviolent protest. For instance, it’s been suggested that the absence of uprisings in the 1970s actually meant there was less pressure against policies of economic austerity policies. Wasow concedes that there is scholarship suggesting that, separate from the 1968 election, violent protests may advance different kinds of protest goals such as catalyzing “increased investments in social policy and other re-distributive policies” to quell unrest. Ryan Cooper notes that “when Martin Luther King was assassinated, sparking days of chaos in many American cities, only a week later Congress passed the Fair Housing Act.” White people might have been more inclined to vote for Nixon, but Nixon also felt the need to expand affirmative action. There are many more outcomes than a single presidential election, and by seeing the ultimate end of “politics” as “which party gets elected to the presidency” we miss a whole host of ways in which protests could be effective or ineffective.

Conceiving of violence as if it is decided on tactically by committees rather than breaking out spontaneously once oppression reaches a boiling point.

When Wasow talks about the political effects of violence in 1968, he is specifically referring to “the expected allocation of electoral votes in the 1968 presidential election under the counterfactual scenario that [Martin Luther] King had not been assassinated on April 4, 1968, and 137 violent protests had not occurred in the immediate wake of his death.” It is worth thinking about the particular violent protests he’s talking about. They came about after Martin Luther King, the leading philosophical exponent of nonviolence in the country, was brutally murdered on a trip to Memphis in support of striking sanitation workers. A white supremacist had just killed the person who had been arguing the most strenuously that nonviolence was effective as well as moral. It’s easy to see how King’s death produced a wave of cynicism about nonviolence. From the perspective of uprising participants, King had been scrupulously dedicated to restraint, and what had it gotten him? Here’s Kathleen Neal Cleaver talking about the aftermath of the assassination:

“The murder of King changed the whole dynamic of the country. That is probably the single most significant event in terms of how the [Black] Panthers were perceived by the black community. Because once King was murdered in April ‘68, that kind of ended any public commitment to nonviolent change. It was like ‘Well we tried that, and that’s what happened.’ So even though there were many people, and many black people, who thought nonviolent change was a good thing and the best thing, nobody came out publicly and supported it. Because even nonviolent change [had been] violently rejected.”

Wasow does not talk about the kinds of raw emotions that people felt after King’s death. Instead, he suggests that the uprisings were a “choice” made by protesters, a choice that ended up hurting them at the ballot box, denying them their goal of having Hubert Humphrey rule over them. I do not think this is fair in its understanding of how the people who participated in these uprisings conceived of themselves. I suspect that if you had tried to explain to them that they were “hurting their goal” of electing Democrats they would have looked at you in astonishment. They already had a Democratic president, Lyndon Johnson, and he was forcing Black people by the hundreds of thousands to go and get shot and psychologically scarred in the jungles of Vietnam.

Here, for example, is Edward Vaughn, a Black Power activist at the time of the 1967 Detroit uprising, describing the feelings behind it:

“During the riots, the people who were looting or taking, the people who were in the streets, the people who were making the rebellion, by and large, were people who lived in the community, just average people. I came across a group of brothers, for example, who said they were just fed up and that they did not want to live like they had lived before, and every night they went out with their guns and they shot at police, shot at National Guardsmen, and of course, went back into their homes… Most of the people were just community people who just had a sense that they were fed up with everything and they decided that they would strike out, That was the way that they would strike back at the power structure… [I]t was the lack of power that caused the rebellions around the country. People did not see any hope for themselves… and I think the masses of people made a decision that they would do something, and I think they did. We felt that we had accomplished something, that the riots had paid off, that we finally had gotten the white community to listen to the gripes and to listen to some of the concerns that we had been expressing for many years… After the rebellion was over, there was a strong sense of brotherhood and sisterhood. We saw more and more sisters began to wear natural hairdos, more and more brothers began to wear their hair in the new natural styles. More and more people began to wear dashikis. We saw a very strong sense of camaraderie in the community—that was all very good for us. We enjoyed that feeling.”

What they didn’t see, of course, was more white electoral support for Humphrey, but how can a social scientist declare unilaterally that that was actually what the protesters wanted, that the dignity and solidarity gains Vaughn describes didn’t matter? Hubert Humphrey likely represented the continuation of things exactly as they were. If their grievances hadn’t been addressed under Johnson, why would electing Humphrey be helpful? The violence in 1967-68 occurred partly out of pure exasperation with a country that just proven that even if you are on your “best behavior” and “play nice” and are overflowing with sweetness and a love of Jesus, like King, you would still get a bullet in your head if you dared to challenge the white power structure. Wasow treats these protests as if they were the product of a committee sitting around trying to decide what the best way to get Humphrey to beat Nixon was, but for most participants, the “tactical” thinking was probably quite limited, and the decision to participate in violence was probably the result of a completely justified anger at a country that persistently denied Black humanity no matter what people did.

Placing protester violence at the center of a story that is about much, much more

I am not sure how applicable the politics of 1968 even are today, given what a unique and complicated time in American history the late 1960s were, and drawing lessons for contemporary activists from the era of Laugh-In and the Beatles seems like something we should be cautious about in general. But zeroing in on the Personal Choices of protesters in the aftermath of Martin Luther King’s assassination seems especially bad because the discourse around riots in this country has long placed blame on the rioters for things that happen as a result of them. (It has a “See what you made me do” quality.) It may sound intuitively logical to say “we should blame rioters for things they cause,” but it’s not: if we have a causal chain in which A causes B, and B and C combine to cause D, focusing on B might be arbitrary, or might be driven by people’s strong interest in not examining A and C. If the thing being “caused” has more than one precipitating factor, or the causal chain started long before the riots, the assignment of responsibility might not be justified.

That might sound confusing, so let me get more specific. Let’s say that we know from observation that if a city’s population is deprived of its rights for a long enough time, and its government is failing its basic functions, there is almost always a social upheaval, usually a violent one. And let’s say that we observe that when these violent upheavals occur, the authorities usually react with repressive measures, which precipitates more violence, which often spirals out of control.

Now let’s say, given these facts that I, a social scientist, decided to zero in on the question “Does the oppressed population’s choice to use violence ultimately make them worse off by encouraging greater repression?” and framed my work around discovering the answer to this. If I did this, there is a very strong sense in which I would be asking the wrong question and my research would give a misleading picture of reality. Of course, conservative newspapers would pick up my research in order to prove that people’s choice to be violent was ultimately making them worse off. But attention would be taken off far more important causes: why are we examining the choices of a population that reacts to oppression rather than exposing the circumstances that led to that reaction? Why aren’t deprivation and lack of services considered the chief “causes” of the ultimate spiral into violence? I, the researcher, may insist that all I am doing is presenting facts, and I do not mean to “blame” people for what they do, I am merely saying that what they do has consequences. But a person who reads my work will be missing crucial context, and I will not be making a useful contribution to public understanding of the social situation.

To give some more parallel examples: let us say that, during the Vietnam War in 1967, while Lyndon Johnson was dropping napalm on babies, I had chosen to publish a study showing that if the Viet Cong put down their guns and adopted nonviolent civil disobedience instead of resisting the Americans by force, there was a much higher statistical chance that Lyndon Johnson would stop depositing bombs on their villages. Or, perhaps during the Iraq War, I could have argued that if Iraqis waved American flags, they would be less likely to be shot by American troops. Or perhaps I could publish a study showing that Palestinians who don’t resent Israel end up better off. At the extreme end, what if, in 1860, the data had shown that enslaved people’s choice to be deferential made them better off than if they were defiant?

The expression that comes to mind here, of course, is “victim-blaming.” I think people who did these studies would loudly insist they are blaming nobody, but are merely pointing out facts. And the first thing we might say in response is: yes, this is true, you do not say you blame them, but by locating a particular party’s agency at the center of your narrative of what is going on, you are implicitly treating them as the most responsible entity. The research could be correct, in the sense that the statistical modelling and data-collection is scrupulous and accurate. But your work will be taken as the only relevant data necessary by people who wish to exonerate the oppressors and direct focus onto the decisions of the oppressed.

These are moral objections, and I think the instinct of researchers is to recoil at moral objections. This is the part where Zeeshan Aleem decided that I do not care about facts, and that I think science should serve political/moral ends rather than Pure Reason. Here’s the thing about this: it’s very complicated. Let’s say I tell you:

“Science should be independent of political considerations. Our understanding of the world should be guided by an independent pursuit of the facts wherever they may take us, not by ideology. It is not for scientists to think about the “political consequences” of their research. A scientist wants to know the truth. If other people misuse their work to promote bad ends, that is on those people, not on the scientists. Facts themselves are completely neutral.”

You might agree with this. It all sounds very nice. It would be nice if it worked. Unfortunately, a moment’s thought should tell us that things aren’t so simple and clear-cut. Truth is multi-faceted: there are multiple ways to look at issues, and many different variables to consider. “Facts” may be neutral in theory, but in practice they are chosen and selected by people who are not neutral.

I suspect you may be getting the jitters to hear me say this, because suggesting that there is an ethical component to the selection of facts suggests that there is “forbidden knowledge,” knowledge that we keep at arm’s length because we don’t like what we think they will do. This is a recipe for censorship, for curtailments of academic freedom. Who is to say what the Bad Facts are?

I don’t think there are inherently bad facts. But I do think there are inherently bad selections and presentations of facts. To take an extreme and controversial example (to which I am not comparing Wasow’s work, just using to illustrate an analogy), Charles Murray writes extensively about observed differences in behavior and “cognitive ability” across racial groups, but chooses not to talk about or think about the hideous multi-century history of racist terrorism that forms a significant part of the factual story. He selects facts that tell a certain narrative, and the problem is with the tale he is choosing to spin, and the way it emphasizes certain facts (which appear to show Black people as personally responsible for their own social outcomes) while obscuring or excluding others (the historical and structural factors that make this story a bunch of bullshit).

I think social scientists have to be honest about what they are doing when they are critiquing activists’ effectiveness. They choose which stories to tell and which ones not to tell. Someone who spins a story about protesters causing Democrats to lose the 1968 election is not telling a story about the way Lyndon Johnson’s disastrous escalation of the Vietnam War destroyed his popularity and made what could have been a relatively successful presidency a moral stain on American history. I dismissed Wasow’s research too hastily, and it was rude, but I do not think the story he has decided to tell is the one we need people to understand.

* * *

By saying that Wasow’s research could be bad “even if being empirically true,” then, I want to be clear: I was not saying that empirical truth doesn’t matter. But we select the truths we disclose. We make choices of emphasis: how much time do I spend talking about factor A versus factor B? Will I mention factor C? Activists object to those who spend more time critiquing activists than critiquing the injustices against which the activists are protesting.

Which brings us to Martin Luther King, who had a very serious problem with people who focus on rioters more than on the things they are rioting about. I mentioned this in my original article, and Wasow says I quoted King’s beliefs “selectively.” I want to be delicate here, because Wasow is Black and I am not and I do not wish to be the person who King-splains my Correct Interpretation of MLK to an academic of color. But I think Wasow and I are actually both quoting King incompletely, and that when we put the two parts of King’s views together, we get something powerfully insightful.

Essentially, there is a thing that always happens whenever a violent protest erupts and people want to consult MLK’s ghost for his opinion on the matter. Those who oppose the violence will cite King’s radical nonviolence, his insistence that violence begets violence and that nothing fruitful can come of riots. Then, those more sympathetic to the people committing violence will remind the first set of people that King called riots the “language of the unheard” and was careful to condemn the conditions that led to the riots just as much as he condemned the riots themselves. King quotes are tossed back and forth like a game of social justice table tennis, with everyone insisting he would have agreed with them were he alive today.

I mentioned King’s insistence that before we condemn riots we need to understand their causes. Wasow suggests this is selective by pointing out that while King did indeed forcefully defend riots, Wasow’s research fully validates King’s ultimate conclusion, which is that violent protests are futile and cause backlash. The exact point that King made over and over to advocates of violence, that it would hurt their goals and set back the movement, is one Wasow says he has rigorously proved empirically. He is frustrated with me, then, for quoting King in criticizing research that is ultimately exactly in line with King’s own perspective.

It’s true that I did not specifically mention that Martin Luther King was an advocate of nonviolence and produced philosophical arguments in favor of the same position for which Wasow produces empirical evidence. But I was not quoting King in order to suggest he condoned rioting; I think everyone knows where King stood on this. I was quoting him because King’s condemnations of rioting contain a hugely important caveat that I think is missing from a great deal of contemporary discussion around violence/nonviolence, including from Wasow’s paper.

In 1964, riots broke out in New York City after a black teenager was shot by a white cop. Here is how historian Philip Goduti describes what happened:

The New York Times reported that people were “shouting at policemen and white people, pulling fire alarms, breaking windows, and looting stores.” The riots were the results of the people speaking out against the death of fifteen-year-old James Powell, who was shot by Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan, a white police officer. The police sealed off a block in Harlem where over thirty people were arrested and five hundred police officers responded. The Times reported, “there was no estimate of the number injured. Scores of persons with bloodied heads were seen throughout the eight-block area… where most of the rioting occurred. Cars were beaten, glass bottles thrown, landing on civilians and police officers. There was a rumor that the police beat another African American, adding to the violence and racial tension already palpable. The crowds were yelling “killers” at the policemen after the officers went to help a young African American girl who was struck by a hit-and-run driver. The crowd continued yelling, “Killer cops must go. Police brutality must go.”

Martin Luther King, the nation’s leading advocate of nonviolence, was asked what he thought about this. And naturally, he condemned it: “The use of violence in our struggle is both impractical and immoral.” But he added:

“I must affirm that the important question confronting these communities and our nation as a whole is not merely that there be shallow rhetoric condemning lawlessness, but that there be an honest soul-searching analysis and evaluation of the environmental causes which have spawned the riots.”

This is consistently how King talked about violence. He always exhorted people frustrated with unjust conditions to be nonviolent, but what he didn’t do is put the actions of those frustrated people at the center of his analysis.

“I feel that violence will only create more social problems than they will solve. That in a real sense it is impracticable for the Negro to even think of mounting a violent revolution in the United States. So I will continue to condemn riots, and continue to say to my brothers and sisters that this is not the way. And continue to affirm that there is another way.

But at the same time, it is as necessary for me to be as vigorous in condemning the conditions which cause persons to feel that they must engage in riotous activities as it is for me to condemn riots. I think America must see that riots do not develop out of thin air. Certain conditions continue to exist in our society which must be condemned as vigorously as we condemn riots. But in the final analysis, a riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it that America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice, equality, and humanity. And so in a real sense our nation’s summers of riots are caused by our nation’s winters of delay. And as long as America postpones justice, we stand in the position of having these recurrences of violence and riots over and over again. Social justice and progress are the absolute guarantors of riot prevention. — from “The Other America”

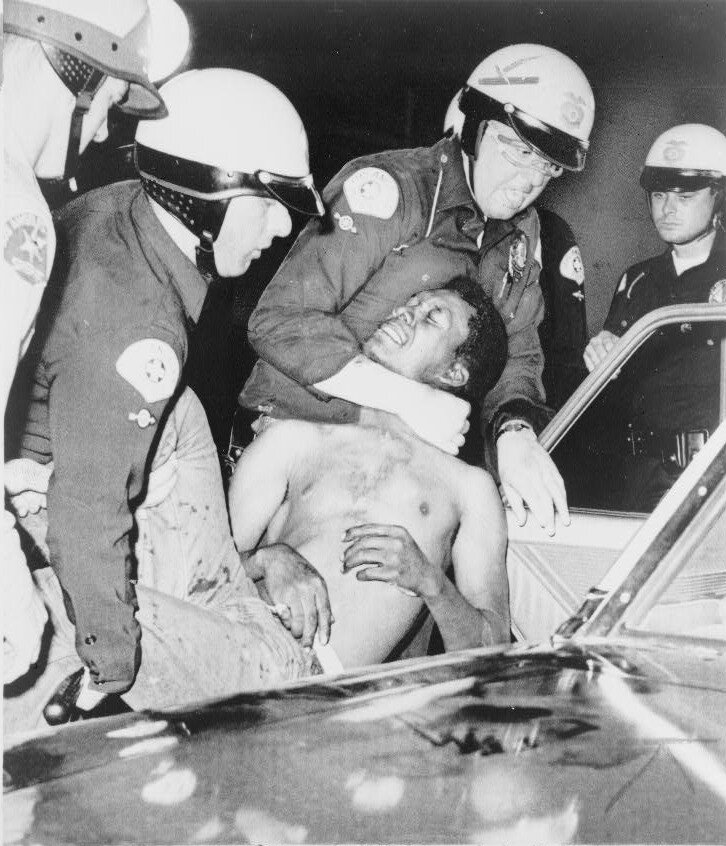

For me, the key phrase there is “as vigorous.” It is not enough to say “Yes, yes, of course social conditions produce riots et cetera, but let’s discuss what riots do.” If we are not spending as much time talking about the causes of riots as the consequences of riots, we are helping America ignore facts that it has consistently “failed to hear.” How many people have ever heard from a resident of Watts in 1965 about what led to the confrontations with police? Where are their voices? Here is a photo of a man being arrested during the Watts uprising:

Where is the discussion of the brutality of the arrests during the riots? To me it seems strange to pursue academic research around the question: “What could that man have done differently in order to better advance his goals and keep the police from being violent toward him?” As I understand King’s speech, that focus frustrated him, too. He condemned violence, but he understood that violence does not take place in a vacuum, that if a country is living up to its basic responsibilities to its citizens, they will not be tempted to burn the whole place to the ground.

* * * *

Wasow replied specifically to my objections and to those of others. He came to the conclusion that I only like Black people who are useful to me, which if true, is something I want to know about myself, because it is disturbing. So I’d like to go through the arguments he gives that led him to this conclusion. He says there are three primary errors: “treating prejudice as immovable, ignoring black agency and treating black leaders, thinkers & activists as monolithic.” Now, I do not think my criticisms of his work do these things, but let me see if I can fairly represent these replies.

Wasow explains what he means by “immovable prejudice” here:

Groups like African Americans & people with disabilities or AIDS have been subject to far-reaching discrimination over many, many years. If the bigotry is deep-seated, then attempts at persuasion are likely to fail… For example, in 1967 Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture) said “Dr. King’s policy was, if you are nonviolent, if you suffer, your opponent will see your suffering and will be moved to change his heart…” That’s very good. He only made one fallacious assumption. In order for nonviolence to work, your opponent must have a conscience. The United States has none.” Carmichael’s pessimism about racist attitudes could be supported by centuries of hard-won evidence.

But, Wasow says, Carmichael was mistaken, because the empirical evidence shows that racial attitudes among white people can be shifted, and protest can be very effective at causing that shift. Decisions by protesters thereby do matter and have political consequences.

I hope it won’t sound too rude if I say that this seems more like an argument against Stokely Carmichael than against me. Wasow seems here to be defending his empirical claim that differences in types of protest have consequences that shape politics, but I have not disputed the factual reality of his claim, only that the framing of the finding’s significance is misleading and unhelpful. I do not agree with Carmichael that the people of this country have no conscience and cannot improve, so the idea that I subscribe to “immovable prejudice” theory is false. I agree that protesters can move the public, and I think we have very strong evidence of that in the shifting public perception in favor of Black Lives Matter.

Second and thirdly, Wasow says that I ignore Black agency and treat Black people as monolithic. This critique is the most important. Here he elaborates:

Even people who are incarcerated under terrible, brutal circumstances have agency to resist domination. Any story that centers white supremacy so totally that black agency is erased from the story is itself ahistorical… More importantly, erasing black agency replicates a certain kind of profound disregard in which marginal groups are not seen as fully human and capable of independent thought and action even against often overwhelming constraints… If white domination and white backlash are the beginning, middle and end of the story, where do black agents of change fit in the story?

Wasow’s argument is that by criticizing him for focusing on the choices made by Black protesters, I am suggesting that Black people are subjected to history rather than making it themselves. I think here we have the crux of why Wasow is so deeply angry at what I said, because to him I was not just calling his research bad, I was advancing a line of argumentation that implicitly dehumanizes Black people. This is because, he says, I essentially think that white people are the ones whose decisions matter: to him, I have a crude picture of the world in which white people choose to oppress Black people, Black people’s responses are predetermined (some respond with violent protest, some do not), and then white people can choose how to respond to that violence. Because I suggested that the focus should be on the conditions that cause riots and the media/public/state response to that violence, rather than the choice of rioters to riot, I am seeing white people as the motor of history.

Here I would like to apologize to Wasow, because I believe any argument I made that seemed to suggest this was clearly badly framed on my part. I do not believe that protesters do not make choices. Nor do I see them as passive. By saying that there were “causes” to the Watts uprising, I do not mean to imply that the people who rioted in Watts were essentially like billiard balls, who do not decide where to go and what to do but whose trajectory is determined by whatever bumps into them. Instead, I am trying to emphasize that people’s choices occur within a context that is not their choice, that they “make their own history but not under circumstances of their own choosing,” that “the tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.” And by saying that the Watts rioting was not decided by a committee, but was a spontaneous act, I do not mean to suggest that people cannot decide how to react to a situation, but that decentralized decisions made by people in desperate and trying circumstances need to be understood empathetically and with a full appreciation of why and how those decisions were made.

Something interesting about the divide between Wasow and myself has to do with how we see ourselves and our roles. Neither of us seems to disagree on the necessity of racial justice protest movements. Wasow wishes protesters to succeed and so do I. But Wasow sees himself as contributing to an intra-protest conversation around tactics, while I am concerned about the conversation that goes on externally to the protests and the effect that certain framings have on that conversation. And one of the reasons Wasow is so frustrated with me is that I appear to be trying to lecture him on how to have an intra-Black conversation around Black protest.

I am reminded here of a different, but somewhat related, century-long intra-Black debate about whether “personal responsibility” and “bootstraps” rhetoric is helpful or harmful. This debate is found in the divide between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois, it is found in Michael Eric Dyson’s harsh critiques of Bill Cosby’s lectures to young Black men, it is found in Adolph Reed taking Barack Obama to task for “affirm[ing] a victim-blaming ‘tough love’ message that focuses on alleged behavioral pathologies in poor black communities.”

This debate, and many “left-right” debates about the social world, is in one way about the ancient sociological question of “structure versus agency.” Are our outcomes determined by the social structure in which we find ourselves or by the choices made by us as free individual agents? This question can become extremely contentious, because the “all agency” perspective (anyone can pick themselves up by their bootstraps) seems a cruel lie that blames people for a failure to overcome impossibly unfair barriers, while the “all structure” perspective seems to treat people as pure victims with no agency. When Wasow says that I deny Black agency, this is what he means: I am dehumanizing people by denying their power to change their circumstances. And when I say Wasow focuses too much on protester choices, I mean that he has neglected structure, reinforcing the idea that the most important thing is to get the oppressed to make better choices.

You will see, of course, as sociologists generally do, that both structure and agency matter and that the difficult question is just how much each one matters and in what ways. But because there are political implications to which one we emphasize, we need to think carefully about how we present things. Agency-focused stories do tend to help convince conservatives that they don’t need to worry about structure; the National Review, of course, happily cites Wasow’s research to tut at protesters for their bad decisions—and like Wasow does not feel the need to talk about the structures those decisions come out of.

One reason that I think Wasow and I differ so passionately, though, is because he sees me as intervening in a conversation that is not mine to engage in, and I see him as ignoring a conversation that he is engaged in whether he likes it or not. He doesn’t particularly like a suggestion that a Black scholar is attributing excessive agency to Black activists, but I feel that he’s not seeing the way the stories told by his scholarship will have important political consequences that it is irresponsible to ignore.

To go back to a hypothetical I mentioned before: let’s say there was a paper showing empirically that fewer bombs would be dropped on Iraq if the Iraqis were nonviolent. If an American academic put out that paper, I would suggest it was absurd. But what if it was put out by an Iraqi academic in Iraq, who saw it as part of the intra-Iraqi conversation about what to do about a fixed external circumstance? It might seem less absurd then, and the American (me) who warned that the paper would be fodder for Americans to blame the Iraqis for their misfortunes might be treated as a meddling outsider whose opinion was unwelcome. Wasow politely suggests that I should shut the hell up about agency and structure, and perhaps I should, but it remains that if the only story being told about protester agency and violence is Wasow’s, then many of the facts will be missing. In the Iraq example: the American dissident should perhaps not tell the Iraqi academic what to study, but the American should certainly work hard to show fellow Americans that the picture presented in that study is incomplete, and to fill in the gaps. The study may be useful as part of an in-group conversation among resisters on how to resist, but when it becomes a tool for the American media to treat “resister agency” as the relevant issue, we have to expose its limitations.

Whether my criticism of Wasow’s research is valid, then, depends in part on what you think that research is supposed to be doing. Is it an attempt to provide a tactical guide for protesters, by zeroing in on the one thing they can control? Or is it an attempt to provide a broad understanding of who has power and is responsible for what outcomes? If it’s the latter, it’s woefully misleading and incomplete, whereas if it’s the former, it’s doing exactly what King did, but with more statistical evidence, though I am not sure violence is “decided upon” the way Wasow suggests. Personally, I think there is a way to do both, by never leaving out the structural context in which agents’ decisions take place, and I think social scientists always ought to be asking the questions: “How is the story I am telling going to be used?” and “In what ways is the story I am telling presenting an incomplete picture of reality?”

* * * *

Let me end by coming back to the question of “politics” and academic research, because the central criticism of my own position on protest scholarship is that I supposedly believe “ideology” rather than “facts” should be the driver of academic inquiry, and that facts that do not serve the goals I like should be downplayed or suppressed. I hope you see that this is not, in fact, the divide between Wasow and myself, because both of us think of protest scholarship as having a purpose beyond the mere discovery of facts. We both think in terms of consequences: he wants to produce research that helps protesters decide which tactics to use, while I want to make sure academic research does not end up handing the right a stick with which to whack protesters while not actually offering constructive advice to protesters. Neither of us is concerned purely with “facts” divorced from “values.” The whole reason Wasow is choosing to study this particular question is that his values make him interested in it. He is guided by a commitment to racial justice, and his desire to uncover empirically the most expedient ends toward achieving that justice. This is good. It is not “unscholarly.”

Our debate is over whether the facts as he presents them end up being misleading and inhibiting the pursuit of the goal. It’s a matter of how we pick facts to assemble stories, and which of those stories are more or less accurate and useful. We are both grappling with extremely difficult questions, and I regret that my casual dismissal of Wasow’s work led us to such a heated conflict, because I do not think there are clear right or wrong answers here. Focus too much on structure and people become disempowered, dehumanized victims. Focus too much on agency and you become a bootstrapper who thinks people are responsible for crimes committed against them by others (while those others are let off the hook). In part, the differences between Wasow and myself do spring from differences in our identities: as a Black scholar he believes in examining and emphasizing Black agency, and as a white social critic I want to call white Americans to task for constantly shifting responsibility onto others without taking any themselves. I believe we are both engaged in the pursuit of facts and truth, guided by intense social commitments. And we both wrestle with that age-old question of the relationship between scholarship and human values, without either having reached a fully satisfactory answer.