How Do We Actually Build Solidarity?

“Solidarity” is a word that gets thrown around a lot on the left. But what does it really mean? And how do we take it from a concept to reality?

At the height of the COVID-19 lockdowns, solidarity took a hit. Pictures emerged daily of people flouting calls from scientists to wear masks, practice physical distancing, and stay indoors to protect vulnerable fellow citizens. A perpetual stream of videos show angry white shoppers throwing a tantrum for being asked to wear a mask. Anti-solidarity selfishness seems to have peaked with armed astroturf protesters storming state capitols to demand that businesses reopen and risk another deadly wave of coronavirus—and the tens of thousands of deaths that must accompany it, simply so people can get shitty bangs at Supercuts.

But then, in a remarkable proof of Newton’s third law of motion, we’ve seen an equal and opposite display of almost unimaginable solidarity in the uprisings that have followed the police lynching of George Floyd. Squads of armed thugs employed by state and federal government agencies have driven armored vehicles into the middle of these overwhelmingly peaceful uprisings (contrary to mainstream reports, the police have been primarily responsible for instigating violence). Cops have also tried to subdue peaceful protesters by firing tear gas, a chemical weapon banned by the Geneva Protocol, and “rubber” bullets, which are only slightly less hard and lethal than metal bullets. When that’s not enough, police have used batons, shields, and mace to terrorize non-violent protesters.

Hundreds of videos depicting police violence have emerged from the protests. The brutality has ranged from battering protesters with batons, pushing elderly people to the ground resulting in serious head injuries, breaking bones, shooting rubber bullets and tear gas canisters at protesters’ faces to blind them (several people have lost eyes), and at least one recorded death that may have resulted from tear gas-related asphyxiation, though a full autopsy report is pending. Grim images of injuries have been piling up on social media.

In response, protesters have rushed to each others’ aid, dousing faces of strangers with water to flush out the cops’ toxic chemicals. First-aid tents and supply tents with basic necessities popped up to freely hand out medical attention and food. Strangers have placed their bodies in front of others to shield them from police attacks. Seattle residents closed off a part of the city to police, calling the space Capitol Hill Organized Protest (CHOP), distributing free food, access to basic healthcare, and cultural events, though this work was marred by reports of violence in and around the area. Police forcibly dismantled CHOP on July 1 and made thirty-one arrests, and yet other mutual aid projects have popped up in cities throughout the country.

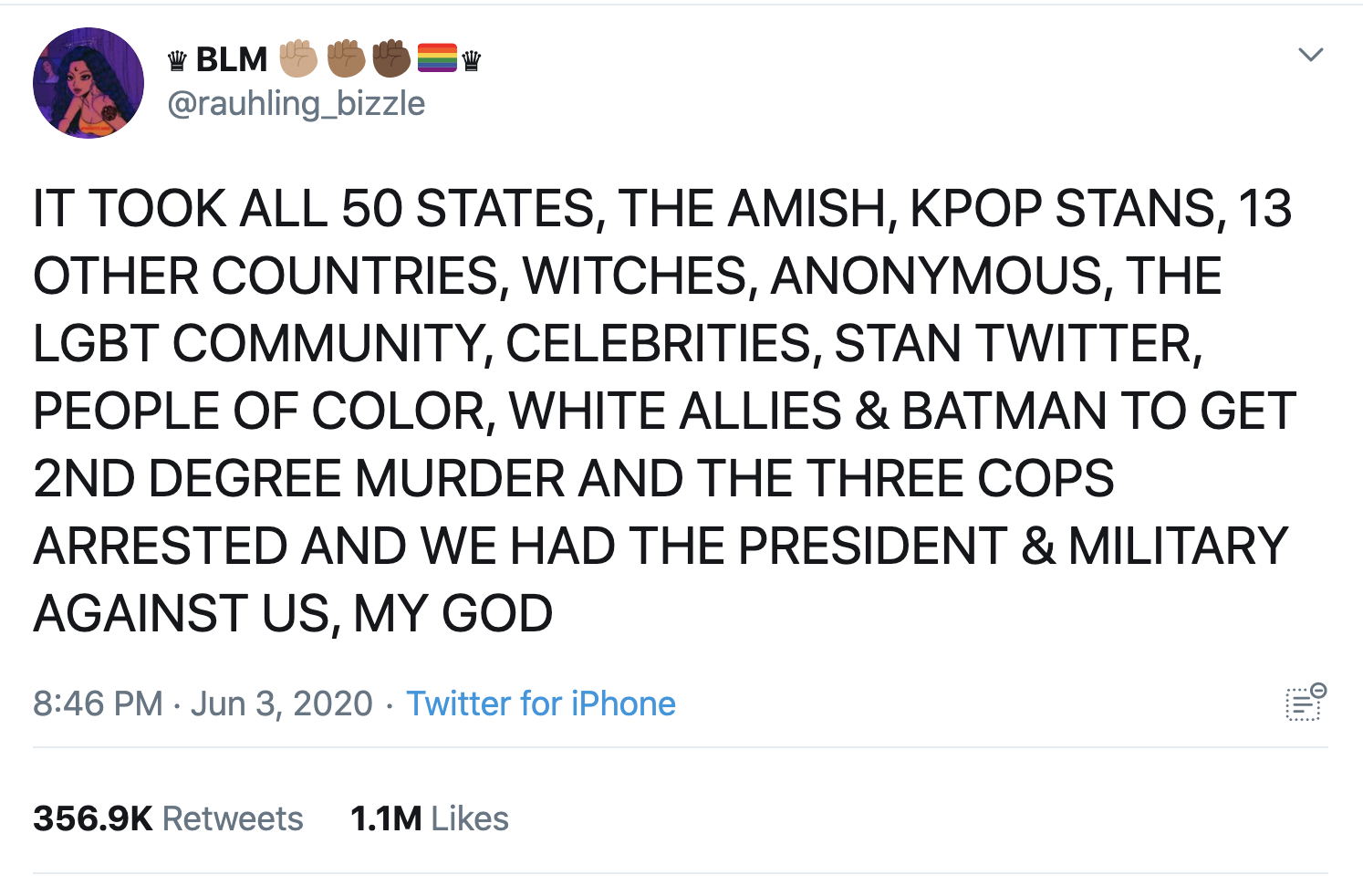

Such solidarity has spread beyond the street, and has made for some truly unexpected alliances.

In a world so full of atomized individuals frequently acting out anti-social competition, callous indifference, and even casual violence against one another, such displays of selfless solidarity inspire both awe and hope. It’s hard to look at the seemingly spontaneous and natural mutual aid practiced by protesters without feeling a surge of faith in our ability to confront the many existential challenges massing on the horizon. But it’s equally hard to look at the deadly cohesion of heavily-armed police units and determine which side will prevail in the long run. After all, we have also seen rather grotesque displays of solidarity between elected officials and police forces, as well as between the police and white nationalist groups.

While they are deeply inspiring, solidarity projects must be sustained beyond beautiful spectacle amidst flare-ups of righteous anger. They must also become a long-term strategic tool that the left cultivates outside the context of protests, demonstrations, and riots, one that is capable of holding together a long-term class project of egalitarian resistance in the face of what will surely be a chaotic century, full of aspiring authoritarians and crumbling political orders.

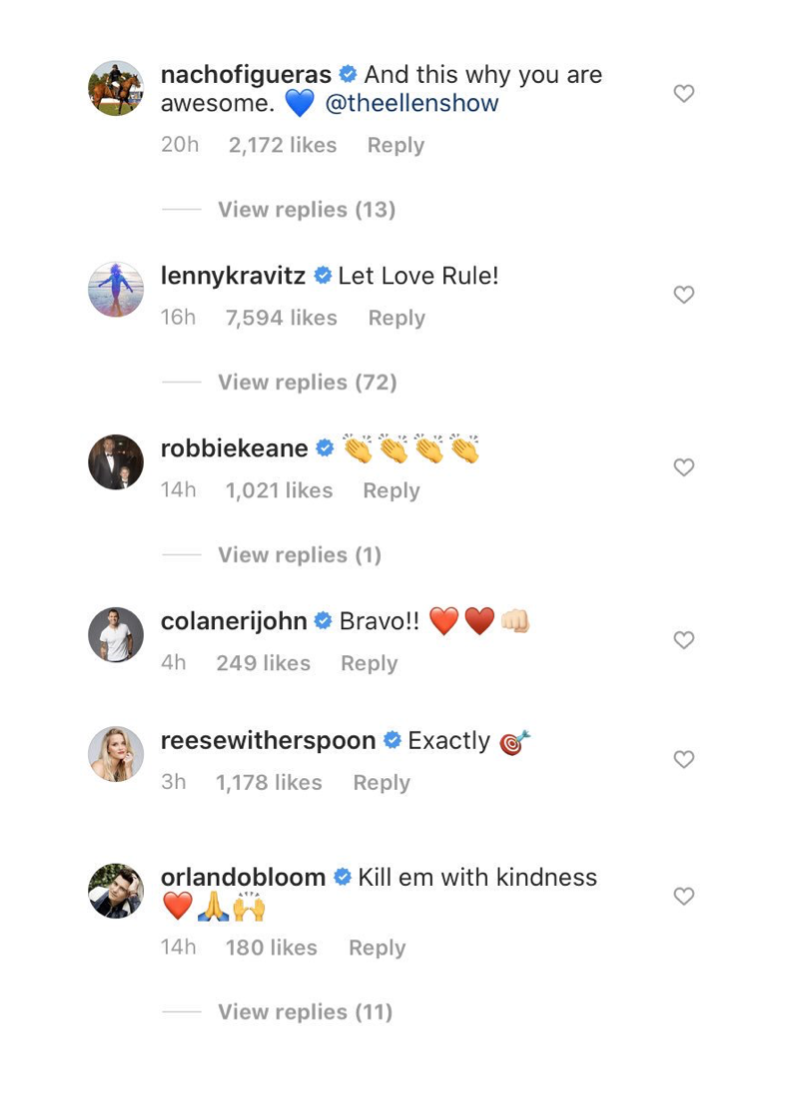

The people who protesters oppose have tremendous class solidarity. Rich people and their lackeys in the cultural industries they own—the classes who built and strive to maintain the conditions that led to this popular anger—enjoy a certain social cohesion conducive to a perverse “mutual aid.” There are many examples of this kind of class solidarity, but one very brazen example that got a lot of attention last fall was when noted asshole Ellen DeGeneres went to a football game with war criminal George W. Bush. After controversy erupted, particularly given Bush’s terrible LGBT record and DeGeneres’s self-promotion as an LGBT advocate, she put out an insufferable video praising herself for being so gracious, and dozens of rich celebrities hopped online to join DeGeneres in patting herself on the back:

While the ruling classes have lots of practice exercising solidarity with each other, they also are skilled at breaking down solidarity between different groups of working class and marginalized people, particularly through the instrumentalization of race. As Courtland Milloy put it succinctly in the Washington Post, “How did wealthy landowners thwart the efforts of enslaved Africans and European indentured servants to join forces in a common struggle for economic justice? Divide and conquer through the invention of race. Make the white servants feel superior to black slaves by virtue of skin color; manipulate poor whites into believing that any perceived gains by blacks had come at their expense.” One glaring recent example of this divide-and-conquer strategy was the concerted narrative shift by many prominent liberal and right-wing commentators to divide Black and white protests by blaming white “outside agitators” for any violence or property destruction. (This is not a new move, either: “white outside agitator” rhetoric was also used to attempt to delegitimize the Civil Rights movement).

Not only does blaming all “bad” forms of protest on supposed white outside agitators remove agency from Black organizers on the ground, all of whom are perfectly justified in burning down police stations and artifacts of gentrification in response to their long-endured repression, it also enables both liberals and fascists to justify militarizing the response while seeking to avoid charges of racism. Trump has used this justification as a means to potentially classify anyone affiliated with “antifa” as a terrorist and traitor. While it’s true that a small contingent of white nationalist “Boogaloo Boys” have reportedly been charged with stoking violence amid some protests to provoke a race war in their quest to establish the United States as a white ethnostate, such stories are more notable for their sensationalism than their frequency.

With narcissistic TV show hosts, war criminals, mayors, police, and cells of armed right-wing terrorists all showing disciplined group cohesion, we’re up against opponents with enviable solidarity. And the only way we will defeat the ruling class solidarity that keeps murdering black people, locking people up in cages, and keeping us all living precarious, overworked, unhealthy lives—not to mention destroying the habitability of the planet—is by building our own long-term projects of class solidarity.

Of course, that’s no revelation. Among the left, solidarity is very often held up as a virtue, to the point of cliche. But it is less commonly discussed as a particular strategic tool that must be deliberately and systematically cultivated. While spontaneous displays of solidarity are encouraging, these kinds of bonds will need to be sustained long-term, outside the street battles, if they are to hold workers together. The real difficulty in building class solidarity in the midst of a militarized, laissez-faire, social Darwinian culture has been woefully underestimated. The general understanding of how to build it and nurture it is too superficial given how important it truly is to achieving the aims of building long-term racial and economic equality.

Some of the first mass movements of the modern era, like those for abolition, women’s suffrage, and labor rights, started with solidarity between members. It wasn’t an afterthought. The causal relationship didn’t go “movement, then solidarity.” It was the reverse. Solidarity was the genesis.

If solidarity was absolutely essential to the success of popular movements, how did people build it? Part of it was due to the nature of the physical spaces in which they lived and worked. Abolitionists in increasingly dense cities could congregate together, and many former slaves had the chance to meet up and discuss the traumas and experiences of toiling in the fields. The kind of work done in new factories and coal mines required workers to collaborate closely—often away from the eyes and ears of bosses. Close collaboration often creates an esprit de corps, a sense of working together on a shared project in opposition to hostile forces.

Solidarity depends on the social cohesion that can be readily built when working in groups with a shared purpose, shared challenges, and shared opposition. An essay in Current Affairs lays out some excellent examples from social psychology research on how to build ingroup cohesion, which is basically a fancy term for solidarity without the explicit class connection. For example, in Muzafar Sherif’s Middle Grove experiment, researchers sought to pit groups of teenagers against each other, but the kids ultimately defied the artificial competition and cooperated with each other against the more powerful adults. Having a clear shared project, opponent, and physical space allowed in-group cohesion to flourish.

But creating these sorts of conditions today is not easy. That’s especially true in an era of social fragmentation and alienation, during a time in which corporations have gotten very effective at preventing workplace solidarity. Beginning in the 1970s with assaults on unions and the offshoring of manufacturing jobs, employers have developed complex systems and strategies to prevent employee solidarity. A whole industry of “unionbusters,” lawyers and consultants who aid companies in “union avoidance,” employ a deep bag of tricks. They use divide-and-conquer tactics, isolating employees from one another and attempting to pit them against each other, often along lines of race and ethnicity. They also use propaganda and deception to prevent workers from unionizing. Many jobs rely on irregular scheduling, which keeps work precarious and makes it difficult for hourly wage workers to get to know their coworkers and build lasting bonds with them. Managers seek to manufacture competition with rewards meant to pit workers against each other, or they’ll overwork and overstretch workers so they have no time to spend with friends. Or, they make conditions so miserable nobody wants to see anyone from work anyway.

Our living spaces, too, are designed to atomize: whether lonely apartments or single-family homes, the spaces we inhabit discourage building bonds and strong relationships with people outside our kin groups. (The age of coronavirus has only made this clearer). Think about your town: how many spaces are open to members of the public and don’t charge money to inhabit them? How many make it easy for people to congregate? Cities are almost entirely shaped by private real estate markets in which developers attempt to profit from the elimination of as much public space as possible. Only about a quarter of New York City is public green space, and about a third of London and a seventh of Shanghai.

Meanwhile, because we’re so drained from the many stresses of the world—unfair or nonexistent jobs, unaffordable healthcare, crushing debt, and existential crises like the global pandemic and ecological collapse—we spend a lot of our free time getting addicted to entertainment that’s meant to ensnare our attention. Around 164 million Americans play video games, and the World Health Organization considers “gaming disorder” as an illness that affects between 1 percent and 10 percent of gamers. This doesn’t mean that video games themselves are to blame, exactly, but that people are so unhappy that they lose themselves in deliberately addictive entertainment. Plus, many of the stories we consume are about lone heroes fighting against collective foes and reinforcing the individualistic myth of the ubermensch. On top of all this are the culture wars very competently manufactured by propaganda networks like Fox News, MSNBC, and talk radio. These attempt to sow division among workers based on surreal disagreements over things like saying “Merry Christmas,” believing the scientific fact of climate change, or wearing a mask to prevent the spread of a deadly pandemic.

For all these reasons and others, there aren’t as many of the same kinds of opportunities for building worker solidarity now as at the beginning of the modern labor movement. Our work is more alienating, our lives are more isolated, and cultural obstacles are more deeply ingrained. So if we can’t rely on close working conditions like the justice movements of the past, how can we build more long-term solidarity within the working class? How can we assemble forces capable of dismantling the big demonic systems now driving us toward collapse?

While we could spend a lot of time daydreaming about the perfect paths to utopian solidarity, there are a few activities that are not particularly difficult and can have outsize roles in building effective class solidarity. That is, they’ve got a big bang for the buck. The three activities below are already happening, but we’re still far from maximizing their potential. Putting more collective energy into the following areas could go much further toward building more real solidarity on the left.

1. Clubs

In the face of catastrophic, existential crises, it may appear naive to suggest starting a leisure club. But it’s hard to overstate how deeply social trust has declined and how vital trust is to building solidarity. Spending leisure time building rapport with people we’d like to bring into our movements is essential to rebuilding trust, and with it, solidarity. While a lot of energy goes to more direct political and community organizing (which is good), too little goes into organizing groups and events that are not directly utilitarian or explicitly geared toward a particular political outcome. Not everything we do for the cause must be predicated on achieving some specific end.

As history shows us, there’s a lot more we can be doing to build solidarity through a diversity of clubs and community groups. From the 19th century onward, networks of women’s clubs were essential in building relationships, solidarity, and standing in communities by hanging out and doing fun things. They had more “serious” purposes too: Black women played a critical role in organizing clubs to pursue antislavery and universal suffrage movements during this time. Later, women’s movements of the Progressive Era emerged from such clubs and ultimately won voting rights for women. (It shouldn’t go without noting that many of these clubs and the white women’s suffrage movement in general were often racist as hell.)

Book clubs, religious clubs, music clubs—or, uh, “bands”—knitting clubs, gun clubs, and even Fight Clubs (the kind that are not sweaty and vaguely fascist) are all ways to build class solidarity. This kind of thing is happening all over the place, though not nearly often enough (yet). In addition to clubs, projects like starting community gardens, community solar projects, housing coops, and other means of generating basic necessities in a cooperatively-owned and cooperatively-run way are another way to build solidarity. All these sorts of group leisure activities help build interpersonal solidarity that can then be directed toward more political purposes when the moments present themselves. The right wing knows this, and has many sorts of clubs that have often bolstered the in-group cohesion of their movements, whether it’s backwoods ethnonationalists LARPing as Vikings, groups of grown men who call themselves “Proud Boys” and “Boogaloo Boys” doing whatever it is those types of people do, or just some respectable suburban racists going down to the shooting range.

Of course, given that COVID-19 is unlikely to go away or be easily contained in the near future, and given the high likelihood that more such pandemics will continue to emerge due to our farming and development practices, organizing these sorts of clubs will be increasingly challenging. Figuring out how to enjoy them remotely or in ways that minimize exposure to infectious diseases is necessary. But since it appears the Black Lives Matter protests have not led to a spike in COVID infections, there is good evidence that people can congregate safely outdoors taking proper precautions.

2. Inter-movement Alliances

Nonprofits like to build coalitions and networks. But they tend to stay in their lanes: environmental groups create environmental coalitions, LGBT+ groups create LGBT+ coalitions, etc. DSA has a bunch of working groups all collaborating together (theoretically). But there’s a lot of room for groups from wildly different issues to be working more closely together, building more solidarity within and between their groups.

Here’s one illustration:

On the same day that the climate action group Extinction Rebellion (XR) held their Declaration Day in October 2018 in London, the Yellow Vest (YV) movement was born across the Channel. While YV has sometimes been caricatured in the media as opponents of climate action, this is a gross misunderstanding. The protests were in part a response to French President Macron’s implementation of a carbon tax that was ultimately regressive, harming workers for a problem overwhelmingly caused by the rich. But in fact, YV has shown support for more justice-based climate action and would be a valuable partner to XR in sharing tactics and building power.

A month after their Declaration Day, Extinction Rebellion launched a Rebellion Day in London. At the same time, Stand Up to Racism was holding an even larger event, a “national unity demonstration against fascism and racism.” Again, this was a missed opportunity for collaboration. Why were these groups in different parts of the city doing different demonstrations? They’re both aimed at building power to overthrow a violent ruling class. These groups and their battles are always portrayed in the media as fragmented, and even seen by many of their participants that way. But they’re not: ultimately, they’re just different manifestations of the same movement. One obstacle, of course, is also that these groups sometimes see themselves as siloed. XR, for instance, has caught flack for insisting on promoting themselves as “post-partisan” or non-political, which obviously hampers their ability to see themselves as part of a larger political movement.

If you’re curious what cross-issue collaboration might look like, try the movie Pride (2014), which dramatizes the true story of a coal miners’ union joining together with an LGBT rights group in solidarity and mutual effort. In the movie, the LGBT group goes out of their way to raise money for the coal miners, for no other reason than the fact that they believe in the miners’ cause. Even though some coal miners are openly homophobic, and significant cultural differences exist between the two groups, this one selfless act builds a foundation of trust. This facilitates more time spent together, which grows into mutual fondness, which creates the solidarity that allows both groups to achieve many of their goals, while simultaneously reaffirming for everyone a sense of shared humanity.

The right has long been engaged in a project of division: separating blue collar workers (particularly white men) from movements that conservative pundits like to describe as effete, effeminate, liberal, coastal SJWs. The culture wars, at their heart, intentionally fracture the working class along petty divisions to prevent worker solidarity, and have given rise to the myth (remarkably popular on the online left) that the “real” working class is white, straight, and anti-woke, when in fact the American working class tends to be ethnically diverse, and trans and disabled people are far more likely to be poor.

One classic example of a deliberately constructed anti-solidarity divide has been between extractive workers and environmentalists. While coal miners have had a huge historic role in building labor power, there’s a lot of cultural animosity between them and environmentalists today in the United States. While the environmental harms caused by extractive workers are certainly an issue, it’s really more of a cultural division stoked by elites, and not always those on the far right. One of Hillary Clinton’s more famous campaign gaffes was her callous comment about coal miners losing jobs (part of her long pattern of showing disdain toward workers).

But this extractive-environmentalist division is not necessary. Some groups like the BlueGreen Alliance have claimed to bridge the divide, but they have so far failed to connect with workers and grassroots greens (in part, I believe, because they lack a theory of power and a commitment to anticapitalism and, like XR, have tried to remain “non-political”). The process of building solidarity between seemingly disparate movements must start with one group reaching out, doing something selfless, spending time with each other to forge friendships, and helping each other build power. Imagine it: police and prison abolitionists working with Climate Justice Alliance; antiracists groups and firefighter unions; anarchists and K-pop stans. There are so many crossovers possible, and many have already happened during these recent demonstrations. It would be a shame not to continue building those networks and relationships, finding shared projects between them that outlast the current crisis. In some cases, it might become clear that vigorous actions will have to be ongoing to continually stoke the fires that forge such connections in the first place.

3. Stories

Something the left hasn’t been good at lately is building a mythology. Marx did a great job of telling a compelling story about how the world works, and the left is still (ironically) resting on his labor. The left has been so focused on getting the facts right and building theory based on difficult scholarly work that it has abdicated an essential facet of winning power: controlling and constructing narratives. This isn’t really the “control the narrative” Machiavellianism you hear in vapid Aaron Sorkin dialogue about manipulating voters or whatever, it’s about creating fictional stories that show the possibilities of leftist victory.

A study by Calvert W. Jones and Celia Paris found that fiction plays an incredibly important role in shaping peoples’ notions of what’s politically possible (and desirable). Fiction has an outsize role on what people believe to be true about the world, even when they know what they’re consuming is fictional.

People order their lives according to material realities, but also according to narratives and mythologies. Those on the right have a huge mythology built by the fact-free narratives constructed by Fox News, talk radio, and a vast YouTube network of Nazis and quasi-Nazis. The right-wing mythology is like a sprawling Marvel Cinematic Universe for the fearful lovers of hierarchy and authoritarianism (a description that might apply to the actual MCU.) Yet the far right also has a huge literary canon. Ayn Rand is probably the most famous example, but a recent piece in The New Republic details the vast fringe literature undergirding an apocalyptic right-wing mythology. Nor is the right’s influence limited to QAnon websites and self-published Amazon e-books. Last year, a Milosevic-defending genocide apologist won the Nobel prize for literature.

Even many mainstream films and stories pander to a right-wing view of the world. To name just one example, Batman is the story of a heroic billionaire beating up poor people. The Dark Knight Rises, the final iteration of Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy, features bad guy populists who sound suspiciously like Occupy Wall Street activists (OWS, incidentally, coincided with the movie’s filming in New York City), while an army of cops heroically run to the rescue.

Contrary to the right wing’s hysterical claims that the entertainment industry is too left-wing (to be fair, they might be right about it being “liberal”), the left doesn’t really have this. The literary world today, from low-brow to high-brow, tends to be either depoliticized, right-wing friendly, or (most frequently) some flavor of boring liberalism. It’s rare to see leftist values depicted in mainstream films or captured positively in literature.

Integral to building solidarity is a set of shared images, stories, characters, and archetypes—a mythology—around which people can bond, understand the world, and come together from different backgrounds to apply a shared sense of meaning and purpose to their lives. Dull grey reality, or even beautiful vibrant reality, isn’t enough. We need the frames of mythology around the vast confusing maelstrom of information and the random tragedies of the world to build relationships, meaning, and a sense of what is possible. There are some recent examples, whether V for Vendetta’s Guy Fawkes masks or Joker makeup, that provide a few stirrings of quasi-leftist mythic aesthetics. But it’s not nearly enough.

There is a lot of work to be done cultivating solidarity systematically so that it may be used as a strategic tool for building class power. But, perhaps more importantly, feeling solidarity is simply a vital part of being human. Building selfless bonds of camaraderie gives meaning, brings joy, and makes our time on earth more rich. Organizing clubs, alliances, and mythologies may be vital for building movements and ensuring the capacity for life to continue into the future, but they’re just as necessary for ensuring that life remains worth living. The increased isolation experienced by those of us in COVID lockdown reminds us how important solidarity is, but also how difficult it can be to build given our current physical circumstances. While much pain gathers on the horizon, and the future carries with it inevitable catastrophes, we can take heart that doing the work of solidarity is still extremely possible: and moreover, it’s what makes us human.