Since the age of four I have liked to be surrounded by books, but it wasn’t until college that I actually started amassing a “book collection.” It started as a single row above my desk, just stuff I bought for class and a few Kurt Vonnegut paperbacks brought from home. Over the next 10 years, the collection grew and grew until it became massively, comically unwieldy. Now it spans five rooms—my living room and bedroom at home, the two rooms of the Current Affairs office, and the lobby outside the office, which is not technically mine to put books in, but I have done it anyway because there is nowhere else for them to go. There is a strict divide between home books and office books: fiction at home, nonfiction at the office. There are hundreds upon hundreds, possibly in the thousands, and when I last moved they took 50 boxes and were by far the most difficult part of the move.

It is not that I have vast wealth to spend on books. It is that, for over a decade now, whenever I have had any extra money beyond that needed to pay the rent and for the coffee and protein bars that keep me alive, it has generally been spent on books. Maintain this habit for long enough and you, too, can have an impossibly inconvenient musty library that has to follow you wherever you move.

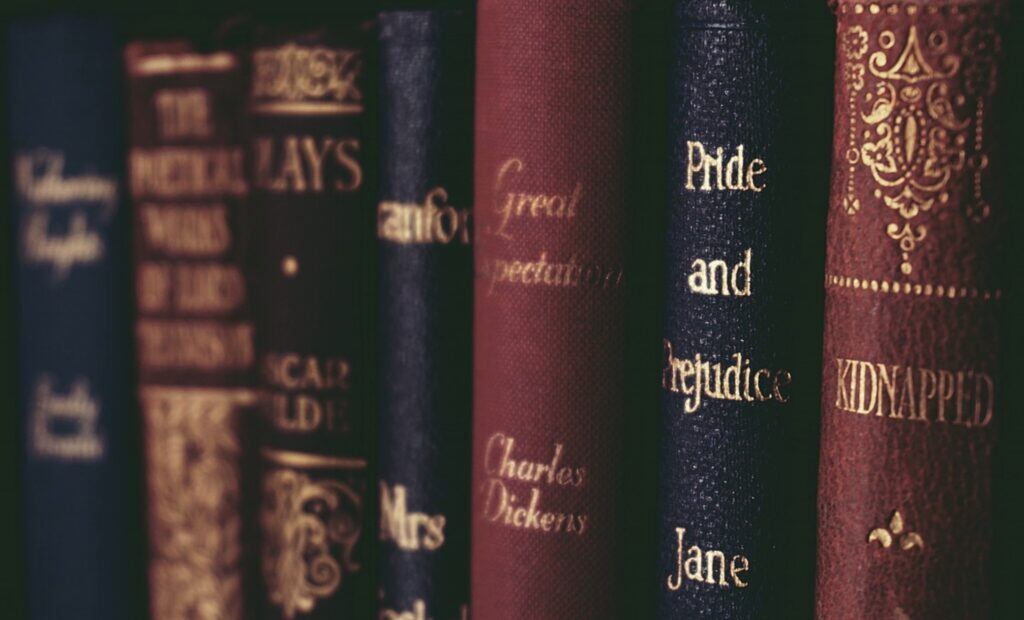

I swear I am not indiscriminate in my selection. I am extremely finicky and particular. But I am still not really a Book Collector. I do not want expensive or rare antiquarian books. I do not care about “first editions.” Cheaper is better, and one reason I’ve been able to accrue so many is that on AbeBooks you can get plenty of books for under $4 each including shipping. But I have idiosyncratic and exacting aesthetic standards. My ideal book is a plain red, green, brown, or blue hardcover with cloth binding and elegant but simple gilt lettering on the spine. I do not like paperback books. If I am sent a paperback by mistake, I send it back. And on hardcover books, I do not like dust jackets. The first thing I do when I get a book is to tear the dust jacket off and throw it away. Books should not be judged by the covers, and so my books must have no covers. This would horrify Book Collectors, I am sure, but I have no alternative. I used to keep all the dust jackets in a big tub, in case someday I needed them. But I was never going to need them, and I was tired of lugging the tub around. So into the bin they now go.

I don’t collect books for the mere sake of having a lot of books. I like the way a nice library looks and feels, but though my family will never believe it when I say this, I have practical reasons for collecting so many. They are not just any old random titles. They are an attempt to have access to the foundations of knowledge at my fingertips at all times, and I’ve picked the things I most wish to have nearby. I use the books all day every day.

“They are my slaves and have to obey my will,” Karl Marx said of his books, with some typically Marx-ish unpleasant hyperbole. I have a different relationship to my books. They are friends, colleagues, advisors, teachers, and adversaries. Having a lot of nonfiction books around is like having a panel of experts who can counsel you at any time on any subject. Having a lot of fiction books is like having shelves full of hundreds of portals to different imaginary worlds.

I estimate that it would take about a decade, at 200 pages a day, to get through all the books if I stopped amassing them tomorrow. Realistically, absent immortality, I am never going to get through them all. But this does not mean they are just “for show”—in fact, many of the books I have I’d rather nobody saw, because I don’t like to be asked questions about them or judged for my choices, which might in many cases be Questionable. The reason for having an unreadable quantity of books is that I never know quite what I am going to need or want at any given moment. My reading habits are erratic: I dip in and out of books like I am sampling fancy cheeses, hardly ever sitting through anything start to finish. It is a habit I have been judged harshly for by many peers, and probably rightly so. A secondary reason for the bulk is that I choose the library carefully so that it maps out what I think of as the scope of useful knowledge—or at least, knowledge useful for the projects I enjoy. My job is to write about politics from a left perspective, so the biggest part of the collection is books about socialism, capitalism, economics, and political theory. But there are sections on law, feminism, Black studies, history, philosophy, natural sciences, sociology, architecture, music, film, etc. My life is generally very disordered, and I am not naturally a person who organizes things, but I am very particular about where the books go.

I do not want to replicate a public library. I try to pick books that are fairly comprehensive or important, in order to actually minimize the number of books on any given subject. I have about 10 books on sociology, for instance, and I picked 10 books that, if you read them, would give you a pretty thorough understanding of sociology. Every book I buy, I buy because I think reading it will give me something. When a book turns out not to be very useful, I get rid of it. I am not a hoarder—though I cannot convince my family of this. I do not cling to books if they displease me. (I do, however, have a section called Satan’s Library, featuring all the right-wing books I have had to read over the years. Ben Shapiro and Ayn Rand are in there. It is a toxic bookshelf, and unfortunately it’s the first one you notice when you come in the Current Affairs office.) I do not want a library that grows infinitely. My books feel like they are currently approaching my ideal number: There’s a good selection on most subjects that interest me. I tell myself that once the library feels “right” I will stop growing it. I have told myself this before, of course, and it has not happened, but I do avoid gratuitously bloating it with books I don’t want. I recently had the opportunity to buy a complete set (48 volumes) of the Collected Works of Anthony Trollope at a reasonable price. It was gorgeous, and I like 19th century fiction. But 48 books by Anthony Trollope is too many. He is worth about one or two slots. To have dozens more books by such a minor writer—one my colleague Adrian Rennix, an expert on the novel, has described as “boring as fuck”—than by Tolstoy or Ursula Le Guin? Unforgivable. It violated the Logic of the Library. The set was not bought.

Strangely enough, I do not like bookshops much anymore. I like the idea of bookshops, of course, and there are some wonderful ones in New Orleans. (Dauphine Street Books, the best of them all—so crammed with books you could barely move, and with the obligatory bookshop cat—is sadly closing, another victim of the present economic disaster.) But I don’t like browsing bookshops because usually I know exactly what I want. I have a long list of books to buy, and I don’t especially enjoy spending time hunting for them.

When I do go to bookshops, I go to used book shops. This is not just because I am cheap, but because old books are better. (The best used bookstore I have ever been to, by the way, is Brattle Books in Boston, which is responsible for building a substantial part of my present collection.) Old books are better because they have histories. I say I don’t care about “first editions,” but I do like books that have clearly passed through generations of different hands. I was recently reading a book that contained a sentence like “depending on which way the present war turns out,” and it had been printed in 1942. Incredible that when the ink touched the pages, whether Hitler would win was an open question.

The older the book, the more remarkable it is to realize that hundreds of years of history have passed and somehow left the book intact, kept safe from events and the elements on shelf after shelf. The little notes and souvenirs you find in the front are the best, though all too rare. Sometimes the book will have come from an unexpected library—it spent 30 years at a high school in Ohio, for instance, and you wonder why they finally discarded it. I have occasionally gotten books that say they belonged to Eric Heffer, MP, a socialist Labour politician who amassed 12,000 books over his life, mostly on left politics. Heffer’s collection now floats around all over the place, and it’s fun to stumble on one of his.

I opened a 1905 edition of The Stories of Guy de Maupassant recently, and a pressed four-leaf clover fell out. Then another, and another. Seemingly every time this person found a four-leaf clover, they had pressed it in the pages of The Stories of Guy de Maupassant. Who did this? When? It could have been anyone, at any time in the last 115 years. When I bought a copy of The Open Society and Its Enemies by Karl Popper, I was startled when a series of family photographs fell out, depicting some children playing at Christmas, dated 1967. Why did these pictures end up in this book? It will forever be a mystery. Sometimes the books have been given as gifts, and are inscribed with the giver’s reasons for the choice. Usually the justification is unpersuasive, and you realize that this was a terrible idea for a gift and was probably quickly discarded. I recently opened up a copy of Felix Feneon’s Novels in Three Lines and found a postcard of a Rembrandt painting, sent from East Germany in 1964. The postcard is addressed to “W.G. Forrest, Wadham College, Oxford, ENGLAND” and reads:

Dear Mr Forrest,

Thanks for the letter and kind offer of a testimonial which I shall take up as the need arises. Meanwhile greetings from the hospitable G.D.R.

D.M. MacDermott

It’s quite easy to find who Forrest was, though MacDermott is a mystery, as is the means by which a 50-year-old postcard from a now-nonexistent country ended up in my book, which was published well after 1964. Did Forrest use it as a bookmark? It is a joy when these little mementos tumble from the pages.

If I am being honest, I am certain that a kind of intellectual insecurity has in part driven my compulsive collecting and devouring of books. I always feel ignorant, and the books help me feel as if, at the very least, I have the ability to end or reduce that ignorance standing beside me. I may not be knowledgeable myself, but the library is a kind of “second brain,” or an extension of myself, a place that contains everything I don’t yet know but hope to. Some of this is stuff I think I “ought to have read,” so you’ll find a lot of “classics” not because I want people to think I have read them (I try to hide these ones away so that people won’t think that) but because I want to remind myself what I would need to know in order to know what other people know. I am certain that some part of this comes from having attended elite universities while coming from a family that did not have college degrees. I always felt at these places as if there was some big secret that a lot of other people understood but I did not, and by tearing through books at a furious pace I felt I could possibly find out what it was—and hopefully destroy it, because I resented the existence of secret knowledge. This sounds quite mad, and I am not even sure if it’s true; I am bad at psychoanalyzing myself. But my obsessive collecting and reading must have some source.

It truly is an obsession, an addiction even. I spend much of each day thinking about books. I place a stack of them next to a big comfy chair and I dive into them and do not surface except to take meals, which I try to keep as brief and utilitarian as possible. This is one reason I almost never have writer’s block—reading a couple of good books should always be enough to stimulate at least one good idea for an article. In fact, I am cursed with too many ideas: I have a list of hundreds of subjects I’d like to write on and books I’d like to review, but if I write continuously from now until my demise I’ll never get to it all.

But it is not just a solitary passion. I love looking at other people’s bookshelves and talking about them. (In the Current Affairs Aviary, our Facebook discussion group, we currently have a post in which people are sharing pictures of their bookshelves. It is fun to note what our readers tend to have in common: always Naomi Klein, always Chomsky, and very often Carl Sagan. They are people of taste, the Current Affairs readers are.) I love getting recommendations, though I tend to hate getting books as gifts—as I say, I have an exact list of what’s next. Nothing is more satisfying than to talk to someone about a book.

What is so appealing about these things? Why is this format of information-delivery so peculiarly enticing? I think in part because books are a bit like going into an isolation tank and experiencing ESP. They cut you off from all distractions, and place the thoughts of another person—a person you have selected yourself out of all the possible people—inside your head. The writer does most of the work, but there is just enough left for you, who have to use your imagination in the act of reading. I do think they are the greatest technology yet invented—virtual reality could reach the point of perfectly emulating the world, and it would have nothing on reading, because part of the joy of reading is connecting so deeply with a single other person. (I’ve recently had the experience, after publishing my first real book, of having people I’ve never met feel very familiar with me because they’ve spent so much time with me talking to them in the form of the book.)

I’d like to think book collecting isn’t inherently shameful. I do have contempt for the rich people who buy books “by the foot,” usually old volumes of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books, in order to make themselves look like intellectuals. But if you choose your books deliberately, and they are all things you would read if you could—and fully intend to, if you should live forever—then a library is no worse than a closetful of clothes or a habit of going to restaurants or any other indulgence. Can one justify a big book collection? I do not know. I have to rationalize it to myself, though, because I could not stop if I tried. Being surrounded by books has become too important a part of who I am. I would feel lost and stupid without them. My books are comrades, and wherever I go they follow.