Smells Like Team Spirit

A personal essay about childhood, popularity, trailer parks, and the meaning of class.

Content Warning: racial slurs.

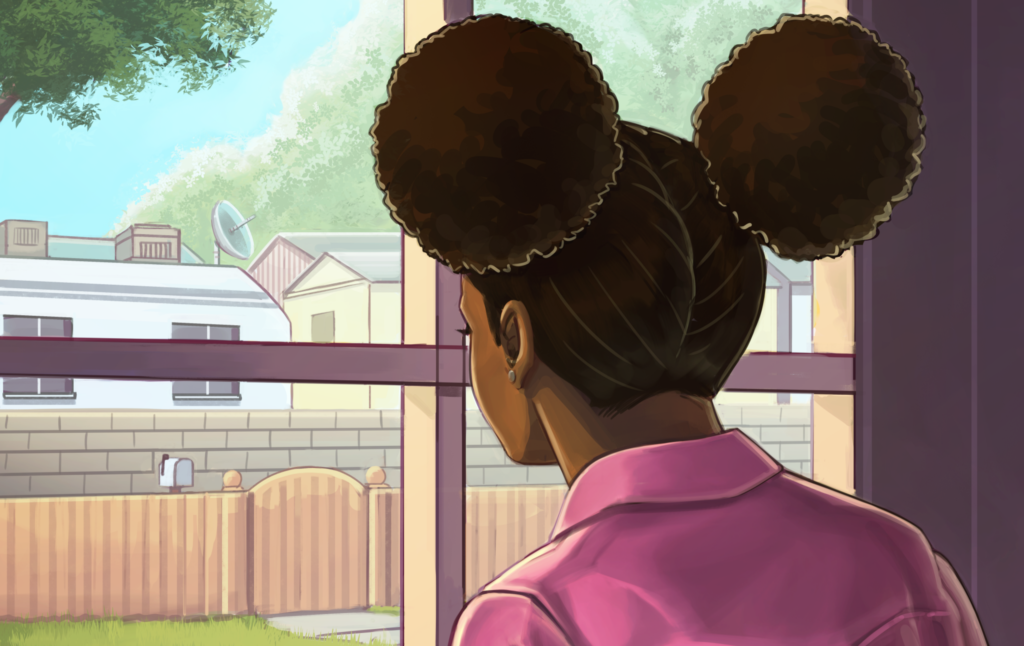

I’d been in America for all of two days when I first noticed the pretty little house on Lucky Lane. A mature tree hid half of it, but there the little house lay, behind a backyard fence and redundant wall. Short and capped with an almost flat roof, its siding—a sort of imitation wood—glimmered queerly in the light. From the window of our bedroom window, I watched the chimes on its porch scintillate in the rare Nevada breeze. Lucky Lane was inaccessible from our street, so I’d never examined the little house up close. But I envied it all the same. The cozy size, just wide enough for two. The singing chimes, so bright and colorful. How nice might it be, I thought, to someday call a house like that one home—for my mom and me, as it used to be. Anything for a bed of my own again.

We lived one street over, on the edge of a ring where the houses matched one another like pieces of an assorted doll set. Ours, like the others, was an obligatory two stories, white garage doors, thirsty lawns in the front, and fenced yards in the rear. Windows lined with shutters that weren’t supposed to shut. Each house finished with horizontal wood panels painted in respectable pastels. A slice of Pleasantville in the high desert. Seven of us were crammed behind this idyllic façade: my aunt and uncle, who’d generously taken us in, their three children—the middle-schooler Joyce, the fifth-grader Nad, plus the baby—and then my mom and me, freshly arrived from London.

By July 2002, daytime Reno felt a lot like a cloudless oven. My cousins and I stayed indoors more often than not. The house was rarely quiet after dawn, starting with our parents, who conducted all communications at a peak-Cameroonian volume, a perpetual sort of shout whose mood required a trained ear to discern. To pass the time, we alternated between taping music videos on BET, and experimenting with sliding down the carpeted stairs (inside cardboard boxes, then outside of them); we practiced our cornrowing skills on Nad’s waist-length hair, and tested each other on American states and their capitals. Dare look bored for a minute, and a floor-length list of chores would materialize. Our parents had no shortage of ideas. We punctuated our play with sterilizing baby bottles and changing diapers, pulling out weeds and cleaning out tilapias for dinner. At any given time, one of us girls either was either hand-washing or dreading her turn hand-washing the bottomless pile of dishes since in this house, a dishwasher was strictly a drying device. A full house meant short showers and sharing beds. But also, an abundance of laughter and tenderness.

I spent much of my free time, that August, studying for high school. Not class subjects, or even my new country’s educational system. Rather, I wanted to know how American kids talked, what they wore, what their school day looked like. My references were outdated: mostly reruns of Fresh Prince, Boy Meets World, and Sister Sister, none of which I’d watched religiously. The last time we’d moved countries—three years earlier, from France to England—I’d trusted my mom with my first day of school. She’d trusted that the British served a free lunch to all students, as was the norm in French public schools. I realized her mistake when the bell rang at midday, and most of my Year Six classmates pulled sandwiches out of tin boxes. Hunger stirred my belly while the clock crawled to dismissal time. Never again, I thought, as I typed the words Wooster High School into my aunt and uncle’s desktop.

Like so much of the internet in those days, Wooster High’s web page was scant and unhelpful. An academic calendar was up with holidays, among them: Labor Day in September instead of May 1, Veterans Day around the Armistice, and something called “Thanksgiving.” One of the school buildings had a façade painted in scarlet red. Each edge was bracketed by a set of horseshoes and, between them, in shiny white paint: Home of the Colts. Nevadans had so many words for horses. Steeds. Mounts. Stallions. Mustangs. One section of the website, dedicated to sports, confirmed what I’d gathered from our neighbors’ front lawns and from browsing the offerings at the Meadowood Mall. This was a nation of teams. It lived to sort people into categories to which it could sell corresponding gear. Colts versus Huskies. Reno Wolf Pack versus Las Vegas Rebels. West Coast versus East Coast. Black versus white. My uncle, it turns out, had a whole talk about the latter. He’d given it to my cousins before. Sensing it come one day, the girls took a mysterious interest in tidying their rooms and left me alone with my uncle.

“You want to know something,” my uncle said in his pronounced accent. “In this America, and you’re not going to believe me, but it’s my job to tell you, in this country, you have to work twice as hard as white people, do you understand? This is a very racist country. Very racist.” I nodded, though unsure what to make of the warnings. It wasn’t that I doubted his experience. My uncle had attended college in Texas in the ’80s, as dark a Black man then as he was now. But we were far from the South, and even further in time from the American cruelty that I’d seen depicted in the TV show Roots. In my 13-¾ years of life, no one had ever called me the n-word. Mentalities had evolved; this was the new millennium! Nevertheless, I promised him that I would do my best.

One other team rivalry, I realized, dwarfed all the others by a long shot: America against the world. How else to explain the obscene display of red, white, and blue flags in places that made no sense? Front lawns, large poles, t-shirts, license plates, eating plates, hats, baby onesies, adult onesies, windows, cupcakes, water bottles, monster truck bumpers. It was as if America feared that people would forget where they were born, or how far they had traveled from their country of origin to get here. I wondered if America had developed this insecurity following that awful day, when I came home from school and stared at our British newscasts, mouth agape, refusing to believe the tiny bodies jumping off the crumbling towers in real time. But my cousin Joyce said her middle school already made her pledge allegiance to America every day before the September 11th attacks.

I peppered Joyce with questions. One year earlier, she’d survived her first day of seventh grade in America without any help. Before that, she’d lived in England with me, and before that, in Spain with my aunt—restlessness runs in the family. I asked how lunch time worked. What were the kids like? What did they wear? What else should I know? Joyce shared everything she could remember. You could bring your own lunch, but there were carts and vending machines to buy food during breaks. A cafeteria offered free lunch if you were eligible for it, as in poor enough, like we were, but the cost of accepting the free meal, particularly in a full lunchroom, amounted to social suicide. So that was out of the question. She wasn’t sure why it was supposed to be embarrassing. It simply was.

Vaughn Middle was, according to Joyce, as cliquish as the American schools on television. Guessing that Wooster High might be too, we lay on our bellies and excavated the glossy pages of her yearbook for data to prepare me. I’d never seen a yearbook before. Each student and teacher got an individual photo with their name and grade. An apt tradition for a nation that could Never Forget. Throughout the academic year, a select group of intrepid students scoured the school to document its layers. If they were thorough, every subculture was represented, from the smokers’ corner to the jocks to the special classes for students with disabilities. The school sent the final layout to a professional printer, and charged something like $60 for each hardbound time capsule. I wondered if my mom would have the money to get me one. Joyce said that buying a yearbook wasn’t mandatory, but what else would you pass around for signatures the last week of school?

There was a club for everyone and everything: chess, Spanish, model U.N., debate, photography, math, Dungeons and Dragons, drama, band, even the yearbook club itself. It seemed the possibilities were endless. The only time students wore uniforms was to compete in various sports, which were played in seasons. Fall was for soccer (football), volleyball, and (American) football. Winter, for skiing and basketball. And spring, for track-and-field, baseball, and softball (baseball for girls). In Europe, high school and university existed for the exclusive purpose of study but here, they were a conduit for school spirit—a sense of pride instilled through fight songs, team colors, and mascot costumes that students wore on game day. Sports were such an integral part of the curriculum that you were allowed, and even expected, to miss class and exams for them. The best athletes went on to do the same at college, in exchange for free or reduced tuition.

Joyce showed me the popular kids in her yearbook. We had them in France and England too, so the category needed no explanation. I knew that popularity was usually a byproduct of exceptional attractiveness or athletic talent. A slim crop of students rose by virtue of their charismatic personalities, though this was not interchangeable with being kind. We combed the yearbook index to get a good look at the crushes Joyce had secretly harbored. She identified the ambitious kids—the ones organized enough to campaign for seats on the student council—and her girlfriends, both true ones and renowned backstabbers. We flipped the pages slowly. Here, she pointed out the ones who’d welcomed her despite her weird Franco-Hispano-Cameroonian accent. And there, some of the girls who’d be at our bus stop on the first day of school.

Two of them, Allison and Amber, were rising freshmen like me. At Vaughn Middle, they’d been popular and popular-adjacent, respectively. Allison, who lived in the pastel ring, was an alum of the middle school’s volleyball and basketball teams. Amber was into cheerleading and lived nearby, too, though Joyce wasn’t quite sure where. She didn’t know either of them well. These girls were white; her closest friends were Mexican or Black, like her loud and uninhibited classmate Brittany. I’d liked Brittany a lot when I met her. She was American but, like me, had been raised by a single Black mom devoted to church—an experience that transcended borders. Over the summer, Brittany had braved the miserable two-mile walk to the Meadowood Mall with us a few times. We went mostly to have run-ins with cute boys, but usually settled for Dippin’ Dots and trying on stuff at Charlotte Russe. As the end of August approached, we made mental notes of the shoes and shirts we’d have to convince our moms to buy at Meadowood instead of Ross, their favorite discount store. Money being tight, always, we knew to be judicious with our demands.

Other categories of yearbook-people were new to me. Cholos and cholas. English-as-a-Second-Language (ESL) kids. But also Loners and Losers, which frequently overlapped. The latter was less self-explanatory. I asked Joyce if accents made people losers. Were we—

No, Joyce said. Lots of people had accents here. (One-fifth of Reno was Hispanic.) The way you spoke didn’t matter…unless you had a speech impediment. Then you might be a loser. The list of sins that landed people on the outs were hard to define with any finality. The most obvious losers had trouble making friends, or shared a visible passion for fantasy fiction—dragons, wizards, spells—that preceded and surpassed the mainstream Lord of the Rings movies. They were the kids who got called creepers because they stared too long, or wore the wrong trench coats to school, unaware that their vibe was more “Columbine shooter” than The Matrix.

I wondered if perhaps some people were just born with faulty wiring that destined them for the edges of society. Innocent heirs to parents who had been losers, perhaps themselves descended from losers. But it was more complicated than that. Loserdom could be reversed, by makeover or a timely growth spurt, just as it could be caught. One vicious breakout of cystic acne, a blowjob to a blabbermouth, or exhibiting sadness past the social expiration date, and you might find yourself in exile. Unless you were exceptionally attractive, in which case, you had immunity. Not all of it made sense. The most important thing was to avoid the stink altogether. Because once it was on you, there was no telling how long it’d linger.

The woman behind the registrar’s desk at Wooster High asked if I planned to take honor classes. The point, I was told, was to prepare me for Advance Placement (A.P.) exams my junior and senior years. The exams each cost $80 but a good score was convertible to college credits, which were pricier down the line. Alternatively, the registrar said, I could enroll in the International Baccalaureate (I.B.) program, which had extra requirements like philosophy and physics. Other than electives like Spanish or Art, most of my classes would be with I.B. and A.P. kids. The registrar pressed me for an answer. I’d have to commit immediately, in part because of the I.B. program’s demanding math sequence: Geometry, Algebra 2, and Trigonometry. Then Calculus senior year. My mom and uncle’s heads bobbed in synchronicity as the registrar played a round of bingo with their favorite adjectives. Rigorous. Challenging. Advanced.

The registrar glanced at my school records. Six schools in eight years. Perhaps I might appreciate this last advantage, she said. Wooster High was the only school to offer the I.B. program in the county, so enrolling would allow me to stay at the school even if my mom and I moved further away than the pretty little houses someday. Attending Wooster for four consecutive years sounded appealing, but I smelled trouble. Setting aside whatever trigonometry was, besides an assured tanking of my grades, I’d be besmeared as a nerd the moment I stepped foot on campus. Besides, the program presented other impracticalities. The registrar wouldn’t know it from my pressed shirt and my mom’s pearly smile, but we had little money to our name: just her last paycheck, a meager child support check from my dad, and what she’d managed to get for our well-used Volvo when we left London. Here, she had no working papers. If she couldn’t afford to buy me a name-brand backpack, where would she find $80 for each I.B. exam? I was plotting out how to accept the brochure and talk my mom out of it at home, when I heard my uncle exclaim, “Okay, let’s do it!”

On the first day of school, Joyce and I walked to the bus stop around the corner. I recognized Allison, the popular girl from the pastel ring, right away. She was around 5’9” but didn’t slouch the way some tall girls did. Her skin was bronzed and freckled, and her hair a natural dark-gold. Teeth perfectly aligned. She wore sweatshirts that said Billabong and Roxy. We made small talk. She said her brother was an upperclassman with a car but who, for whatever reason, wouldn’t drive her to school. American families were strange like that. Amber arrived from Lucky Lane minutes later, with her older sister Cristel and Cristel’s best friend Mickie. By then, Allison had returned to her phone at a respectable distance. I wondered if she was shy. She’d greeted Joyce and me but only because we’d said hi first, I think. This was more than she’d given the Lucky Lane girls. With them, Allison hadn’t even bothered with a nod. I thought at first that she’d been too engrossed in her phone, but she went on to ignore their presence the rest of the week, and every week after that. Stranger yet, the Lucky Lane girls didn’t seem offended.

I wasn’t blind to how shiny Allison looked next to the other three high-schoolers. Mickie had thin eyebrows that she penciled over in thick brown, and wore a dark lipstick that made her face even paler. Her teeth were crowded though that didn’t stop her from smiling big and loud. Most days, Mickie sported a pair of black jeans faded with wear. Her sweatshirts were loose, as if inherited from larger boyfriends who smelled of stale cigarette. She was short but took up space. I gathered that how others felt about it was not her problem. Cristel, on the other hand, looked a little lost when Mickie skipped school, like a shadow in want of a human to trail. I remember that she smiled at jokes on a slight delay. By her own reports, Cristel dated boys who treated her like garbage. Her round cheeks and surprised eyes made her seem fragile. That first day of school, I’d mistakenly thought her younger than her sister Amber.

Cristel and Mickie were juniors at Wooster High, so I could see why they might not care about Allison’s coldness. They were preoccupied with older boyfriends whose every motion—calls/no calls, texts/no texts, visits/no visits—generated an immense supply of material for them to analyze on the school bus. But I remained baffled that Allison and Amber were not friendly. Not just baffled. Bothered. It wasn’t simply that they were pretty-faced blondes who looked like they might get along. They were also the same age and had lived around each other forever, Allison in the pastel ring, and Amber in the pretty little houses. Every morning, for years, they’d awaited the school bus 10 feet apart. The two of them shared a ton of friends. And while Amber’s clothes were fewer and more worn-out than Allison’s—you could tell three weeks into the school year—these girls obviously liked the same surfing and snowboarding brands.

I struggled to put my finger on why the bus stop division troubled me so much, even though their friendship wasn’t remotely my business. Some mornings I chatted with Allison or Amber, but we three freshmen girls always gravitated to our actual friends when the yellow bus pulled up. I had no particular investment in their relationship, or lack of it. The I.B. program had isolated me with fellow nerds, which meant no classes with either Amber or Allison. Yet, every morning, I watched them ignore each other, and wondered how my study of the yearbook had failed to predict this outcome. It was as if an invisible barrier separated Allison from the Lucky Lane girls, and none of them were curious about what lay on the other side.

As the fall semester unfolded, my new classmates taught me a slew of Americanisms. Bins were called trash. The loo or toilet was a bathroom, and sometimes a half-bath, despite having no bathtub in it. Rubbers were always erasers unless you meant to say condoms. As for the little houses on Lucky Lane, the ones I found so charming, they were trailers. And the people who lived in them: trailer trash.

In my mind, the word trailer conjured images of caravans attached to trucks, or the aluminum container in the middle of the basketball courts where Wooster High made its ESL students take classes. But trailers could look like the pretty little houses behind the pastel ring, too. Single-wides that were 10 feet across, and double-wides that spanned 20 feet, although older models could be as small as eight feet. Much later in life I’d learn that, starting in 1976, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development imposed construction standards that vastly improved the fire safety, insulation, and overall shelf-life of these “mobile homes.” The mandated changes had brought the structures closer to permanent housing than their predecessors, rendering them harder to pick up and move in lean times. Only the federally-compliant models counted as manufactured homes, though. Older houses, like most of the 187 double-wides on Lucky Lane, built in 1971, would never get to be anything other than trailers and mobile homes.

Trailer trash, I learned, was a derivative of white trash. If you asked people what white trash was, the definition tended to soften. White trash became a person with no cultural class, the kind who misbehaved and broke social norms. Odd thing was, we all knew kids with money who technically had no cultural class and yet didn’t quite fit the white trash mold. They had parents with criminal records, parents who smoked cigarettes indoors, parents who forgot to pay the electricity bill, who had disabilities, who got laid off, who lost custody. Rich kids weren’t immune to other kinds of markers for low cultural class either, like catching lice or chipping front teeth. Every year, at least one of them temporarily lost their driver’s license to a DUI. My senior year, the wealthy dad of a boy in town—and close friend of several of my I.B. friends—murdered the boy’s stepmom after being ordered to pay spousal support. He’d then tried to take out the family court judge using a sniper rifle, before escaping to Mexico where he was promptly caught. But of course, no one would describe that family as white trash.

It was doing the above while poor that transformed these acts into failures of character. You could be as kind and polite as Amber, you could join cheerleading, wear the right clothes, and date upper-middle-class jocks, but if you lived at the Lucky Lane Mobile Home Park, there was no getting out of it. You were white trash. Which is to say, it wasn’t about cultural class at all. People just didn’t like to admit the required components of so-called trash: whiteness, poverty, and sometimes trailers.

The closest equivalent to trailer trash in my French hometown were the gitans, a nomadic population of Roma that had emigrated from eastern and southern Europe. I remember seeing them in the grocery store parking lot when I was little. The children, tan-skinned and smudged, ran up to my parents and asked to clean our windshield in exchange for a few coins. I don’t think those children went to school. They lived in camps near the pond and behind the municipal gym, near where my dad still lives. Clothes hung on ropes between their caravans. Every few months, local police appeared unannounced and the Roma camps vanished for a season or two. But in the end, they always returned. There were no banners against them, no hostile signage or ads in the windows. But I understood from a young age that they were not welcome in polite society. People held their children and wallets closer when the Roma approached. They scowled when the Roma asked for money. Storekeepers didn’t bother to invent a reason before asking them to leave.

But the concept of trailer trash operated differently in America. It wasn’t directed at so-called ethnic whites, like the Roma who were brown year-round, or the recent comers whose first language wasn’t English. Blacks and Mexicans could be a lot of things—at my school: beaners, wetbacks, ghetto—but white trash belonged to white Americans born and raised in this country. It was for them and by them. A means to denote the wrong kind of whites, short of stripping them of their whiteness.

There is something about temporary housing, about caravans and mobile homes, that causes the people who move in them to lose value faster than a car driving off the sales lot. When Hurricanes Katrina and Rita devastated the Gulf Coast in the summer of 2005, my junior year of high school, the Federal Emergency Management Agency would house thousands of storm refugees in trailers across Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. As early as October 2005, the Department of Labor would find that the trailers were essentially toxic cans, oozing high levels of formaldehyde—a gas that would, in time, cause the trailer occupants to contract respiratory complications and in some cases, cancer. A scathing report by the Inspector General for the Department of Homeland Security later revealed that “[w]hen [the federal agency] did learn of the formaldehyde problems, nearly a year passed before any testing program was started and nearly two years passed before occupied trailers were tested and the occupants were informed of the extent of formaldehyde problems and potential threats.” Sometimes, I wonder if these evacuated folks—now, trailer people—ever stood a chance.

There can’t be any honor innate to the concrete and bolts that connected the pastel ring houses to the ground. Nor is there any particular grace in property titles, which are so often a mere formality. Most of the pastel ring residents, my aunt and uncle included, didn’t own these homes outright. The buildings were mortgaged for hundreds of thousands of dollars, pursuant to contracts that allowed the banks to change the locks on the doors if any of them fell too far behind on payments. But even s0-called outright ownership is ephemeral. Houses are not buried with the people who claim them. Their walls and floors are no more an extension of us than our cars. What housing isn’t temporary?

The trailer’s fundamental sin is, I think, its failure to pass. Apartment buildings and mortgaged houses leave open the possibility that their inhabitants are squarely within the middle class or higher, that they’re able to weather hardship in place, or afford a similar apartment or house elsewhere should they have to. You might never have reason to think otherwise, not until you’re inside anyway. But trailers foreclose that possibility. 10-feet-wide evidence of coveting a piece of the American dream—a lot in one’s name, a stake in the land—and coming up short. The trailer is an admission of the best its owner can do: a $50,000 aluminum box removable during hard times, voluntarily or by force. In many instances, a landlord owns the land on which their trailer is parked. In Nevada, this imbues trailer park residents with legal protections, but in 18 other states, they assume the burdens of both ownership and tenancy. This makes them responsible for the upkeep of their trailer, yet at the mercy of a landlord’s rules and whims.

The trailers’ very existence is a threat to real property values. Developers wall parks of them away from freshly painted rings of subdivisions. Realtors downplay their proximity. With financial equity at stake, the market isn’t going to pretend that trailer residents possess the right kind of class. And with social equity at stake, Allison wasn’t going to pretend that Amber did either. My cousin Joyce and I were safe to acknowledge, though. Living in the pastel ring masked our poverty and excused our Blackness. It had allowed me to pass.

Americans liked to say that everything sounded more intelligent in a British voice. It was facetious. Yet, I understood that my strange European accent legitimized my presence to my classmates; it made me seem deserving of sitting in these advanced classes. Perhaps it’d had the same effect on the registrar. My best friend Caitlin and I were the only Black students in the I.B. program’s class of 2006. She was half-white and middle class; and people liked to joke that she, too, “sounded” white. If the registrar had invited other Black students around town, or even in the rest of my freshman class, to join the I.B. program with the enthusiasm she’d extended to me, it was not reflected in our class numbers.

The I.B. program was full of kids zoned for the Galena High and Bishop Minogue High zip code, where the median income was $91,000, double Reno’s overall median income. My classmates were good kids: smart, thoughtful, curious, and surprisingly well-rounded for teenagers. As I acclimated to this country, they were patient and generous with me. I feel fortunate to have been stuck with them for four years. But underlying their openness to me, I think, was the incorrect assumption that I was a Black and foreign version of them. An upper-middle-class transplant of sorts. Most of them were unaware that, our freshman year, I shared a house with six relatives and a bed with my cousin. Or that my mom and I couldn’t have come up with the money to even rent a trailer of our own.

We were well into the fall of my freshman year when I discovered what team American life had sorted the Lucky Lane girls. For the year or so that I lived in the pastel ring, we continued to say hello in the mornings. But I wish I could say, with confidence, that I would’ve been as friendly on day one, had my careful study of the yearbook revealed that these were the wrong kind of white girls. Only, teenage cruelty knows no bounds. It was better not to have known in those first weeks, so drawn out and dull, yet precious in their innocence. The last summer that trailers were simply pretty little houses.