Growing up in the church, as many Korean-Americans tend to do, I remember hearing about the story of Adam and Eve quite often. As an unsophisticated teenager more concerned with “worldly” things at the time, I never reflected too deeply on the ancient Near Eastern story appropriated by Christians to explain how everything in the world sucks because the first humans screwed everything up.

But, I have to confess, there was one part of the story I always found funny. In between the really cool bits about snakes getting their heads crushed by heels and people returning to dust, God tells Adam and Eve that their previous idyllic experience in the Garden of Eden is over, and that they, along with the rest of humanity, are actually going to have to work for a living. The very ground itself has become cursed because of their transgressions, and survival will now require labor. I had always thought that that was a rather overdramatic way of describing the origins of work, and that the Near Eastern author(s) must have written it because they really hated their job(s). While I was too young to have a job at that point, I felt sincere empathy for the situation; I compared it to the loathing I felt when doing my homework.

The reason I share this story is that it presents a strikingly different attitude towards work than the one promoted by our capitalist overlords. The impression we get from this familiar narrative, written by people from a culture, time, and place far removed from ours, is that work sucks, and it only exists because some people named Adam and Eve ate some damn fruit. In contrast, work is now seen more as a blessing than a curse. In our 21st century American capitalist dystopia, we are often told to love work itself. Commonplace mantras like “do what you love,” abound, but these seemingly benign phrases are actually wielded to devalue, rather than make us cherish, our work. “Do what you love” is phrased as a commandment, not a mere lifestyle recommendation; if you fail to love your work you have failed to obey. In many cases, being “passionate” about your job is another nebulous buzzword like “dynamic,” and “flexible,” which function not just as random descriptive adjectives but as job requirements. It’s no longer enough to show up and do your job; now you also have to enjoy being a wage-slave.

It’s not just ancient Near Easterners who would find our American attitude towards work mystifying; some American work “habits” that foreigners find incredibly toxic include working extremely long hours, almost never going on vacation, barely taking any family leave, not taking sufficient breaks throughout the day, and sending emails after work hours.

While these toxic American work “habits” are clearly the manufactured result of constant corporate propaganda and capitalist domination of the state—resulting from the vicious suppression of leftists and the labor movement by the American government on behalf of the ruling capitalist class, starvation wages, the United States’ status as one of the few industrialized countries that doesn’t guarantee paid parental leave or paid vacation time by law—one can also make the case that some degree of the American work “culture” is real, in the sense of being deeply internalized.

Here are some findings that many of us might be familiar with from personal experience: Although not all employers grant their employees much paid vacation time, many American workers fail to use all their vacation days because they feel guilty about missing work. Even when workers aren’t on vacation, they often feel guilty if they’re not being productive with their free time; hence why there are plenty of articles telling us how to beat “productivity guilt” (and still be more productive in the process). There are many Americans who think being busy all the time is a sign of how important they are, brag about working ridiculous hours and even pretend to work longer than they actually do. Is it any wonder that there are articles claiming that Americans have a new religion that can be called the “Gospel of Work”?

No matter how you look at it, laziness—the state of not working and being happy about it, too—seems to be universally despised in the United States. Consider the notorious examples of Republicans engaging in racist dog whistles, such as Ronald Reagan attacking the nonexistent epidemic of “welfare queens” who supposedly drove Cadillacs and defrauded the welfare system to avoid work. There have also been racist comments by overrated “gurus” like Paul Ryan claiming that America has a real “culture problem” of “men not working and just generations of men not even thinking about working or learning the value or the culture of work.” And then there’s Trump’s attempts to strip healthcare, food stamps, and disability benefits by requiring ineffective “work requirements” to make sure the lazy aren’t gaming the system and help keep up the pretense that Republicans care about the deficit.

Republicans are not solely to blame here: There’s a solid bipartisan consensus on the distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor. Joe Biden himself, in keeping with his racist history, channeled Reagan when he warned about the dangers of “welfare mothers driving luxury cars.” Even when Democrats follow Bernie Sanders’ leadership in championing a $15 minimum wage, we often hear him and Democrats like Chuck Schumer and Bobby Scott carefully adding qualifiers to eradicating poverty when they say things like “No person working full-time in America should be living in poverty,” or “no American with a full-time job should be living in poverty.”

The obvious implication of this kind of rhetoric is that there are some people who deserve to be in poverty (those who refuse to work, or work enough, aka “the lazy”), which ends up condemning involuntary part-time workers, the unemployed, and many disabled people to poverty in practice.

This happens despite varying degrees of credible explanations for poverty, ranging from describing unemployment as an inevitable result of recessions in capitalism’s systemic business cycles, a consequence of the Federal Reserve’s tinkering with interest rates to lower inflation, a persistent trade deficit that props up the value of rich people’s dollars, massive job displacement by machines, people studying the wrong thing in college, an alleged “skills gap,” and the lack of job opportunities for people who have committed felonies once they leave America’s prison-industrial complex. This all in combination seems rather plausible, rather than some nebulous lack of work ethic.

But hey, why bother presenting a nuanced picture by explaining basic economics and the interrelationship between larger social and political forces when it’s much easier to dismiss all or most of the poor as “lazy” instead?

Prior to the 21st century, there were widespread expectations that the new millennium would usher in a new age with a lot more time for all of us to lollygag and laze around. The influential economist John Maynard Keynes published a fantastically optimistic essay in 1930 called “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren,” in which he predicted a 15 hour workweek by the beginning of the 21st century. It may be hard for those of us living in the present to indulge Keynes’ imagination, but he wrote: “For the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem… how to occupy the leisure.”

Anthropologist David Graeber has described the disappointment felt when the “set of assumptions” and a “generational promise” about what the future would look like—for children born in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s—failed to materialize at the turn of the century. The “technological wonders” of flying cars, teleportation pods, and colonies on Mars are still nowhere to be found. A 1957 New York Times article seemed to articulate this generational promise when it explained how the “increasingly automatic nature of many jobs,” along with a “shorter workweek,” would lead an “increasing number of workers to look not to work, but to leisure for satisfaction, meaning, expression.”

Of course, one doesn’t need to go to a Bernie Sanders rally and hear him talk about how Americans are working longer hours for lower wages to realize that fantasies of a “postwork” future thanks to technological advancement under capitalism were, and always will be, a giant fraud. Instead, we currently have presidential candidates like Andrew Yang running around telling people that the robots are going to steal their jobs, and that we have no alternative but to accept a universal basic income and resign ourselves to a bleak future of permanent unemployment because “it’s necessary for capitalism to continue.” But why is it necessary for capitalism to continue, especially if this shitty future is all it has to offer us?

In reality, technology has not freed us from the drudgery of our bullshit jobs; one could argue that it has actually increased the amount of bullshit in our jobs. With our shiny new technology, employers can harass employees with calls, text messages, and emails outside of work. Amazon has patented heinous wristbands that alert Amazon when workers “are slacking off” or “taking too long” in the bathroom. The company even has an automated system that constantly tracks worker “productivity” by monitoring “time off task,” which automatically generates warnings for workers who break from scanning packages for too long, and penalizes their drivers if they take a route their app deems “inefficient.” An increasingly large number of people in the extremely precarious and unstable gig economy take orders through apps from predatory corporations like Uber, where some “contractors” experience working conditions so desperate that they commit suicide.

So if technological advances under capitalism were supposed to result in a “postwork” future, or at least spare us from demanding physical labor, but has in reality only resulted in hard, thankless work and/or a bare subsistence income from crushing unemployment, why should laziness be something that is condemned?

It’s not even clear that we fully understand what laziness actually is, although I’m sure all of us have experienced moments of what we consider to be laziness in our daily lives. There are strong counterintuitive—yet perfectly plausible—arguments from social psychologists that laziness is not merely an unwillingness to work, but also a way of dealing with complex emotions and situations. Some people would even argue that “laziness” is merely a myth and a convenient default accusation that allows people to avoid asking deeper questions about what lies behind procrastination and the aversion to performing certain tasks. What many people consider to be a “lazy disposition” might be better explained as paralyzing fear and lack of self-confidence in one’s ability to accomplish a task, a need for nurture or relaxation, passive rebellion against a task or a person, or even outright depression preventing people from doing something as simple as getting out of bed.

But another reason to resist condemning laziness is that the accusation of laziness has consistently been weaponized throughout history by the powerful against those with less power, successfully justifying theft, exploitation, and massive inequality.

Racist caricatures of lazy Black people didn’t start with Ronald Reagan. Long before his time, white slaveowners considered their enslaved subjects to be “lazy” and in need of moral instruction toward proper work ethic. In Frederick Douglass’ 1863 lecture “What Shall Be Done With the Negro?”, he described the absurdity and irony of this designation of “laziness” when slavery was one of the major foundations of the U.S. economy and most of the European colonial economies in the Americas from the 16th to 19th century. Referring to the “cotton famine” resulting in mass unemployment and misery in Europe when Union forces blocked southern exports of slave-produced cotton during the Civil War, Douglass wrote, “It had been said that the negro was lazy, and would not work. This has been the favorite talk even of slaveowners; but how happened it that all Europe was at the point of starvation the moment the industry of the negro was interrupted?”

It’s highly plausible that the slaveowners who propagated the stereotype of the lazy black slave knew they were being cynical, since every immoral project—especially an institution as abominable as slavery—requires some kind of moral justification, no matter how ludicrous it may be. Fanny Kemble, a noted 19th century British actress, observed that the Antebellum South designated “hard work” not as the province of white people but as a marker of slavery:

No white man, therefore, of any class puts hand to work of any kind soever. This is an exceedingly dignified way of proving their gentility, for the lazy planters who prefer an idle life of semi-starvation and barbarism to the degradation of doing anything themselves; but the effect on the poorer whites of the country is terrible.

I speak now of the scattered white population, who, too poor to possess land or slaves, and having no means of living in the towns, squat (most appropriately is it so termed) either on other men’s land or government districts–always here swamp or pine barren–and claim masterdom over the place they invade, till ejected by the rightful proprietors. These wretched creatures will not, for they are whites (and labour belongs to blacks and slaves alone here), labour for their own subsistence.

Perhaps more fascinating than the palpable hypocrisy of white slaveowners accusing their slaves of laziness is the highly plausible scenario that this stereotype might have arisen, in part, from slaveowners misinterpreting their slaves’ acts of passive resistance (such as working slowly or shoddily, faking illness, or destroying their own tools) as evidence of shiftlessness, stupidity, and genetic deficiencies, rather than the desire for freedom. In The Gift of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois described how slaves would often avoid strenuous labor as a measure of resistance to their masters:

As a tropical product with a sensuous receptivity to the beauty of the world, he was not as easily reduced to be the mechanical draft-horse which the northern European laborer became. He … tended to work as the results pleased him and refused to work or sought to refuse when he did not find the spiritual returns adequate; thus he was easily accused of laziness and driven as a slave when in truth he brought to modern manual labor a renewed valuation of life.

When white settler colonialism was displacing Native Americans from their land, John Locke—a philosopher venerated in American history because of his influence on the founding fathers’ conception of property—was one of the earliest white people to accuse non-white people of “laziness.” He argued that Native Americans were not entitled to lands they had been living in for centuries because they didn’t “labor in” or “improve it,” which was related to his central thesis that agriculturalists who mix their labor with the soil are entitled to it (conveniently the kind of “labor” that European settler colonists practiced). However, investors like Locke didn’t actually labor in agriculture themselves, meaning by his own formulation, Locke and other members of his class were too “lazy” to have property rights. To get around this, Locke argued that gentlemen like himself were entitled to land because the labor of their servants counted as an extension of their masters’ labor. As Locke argued in his famous Second Treatise of Civil Government:

We see in commons, which remain so by compact, that it is the taking any part of what is common, and removing it out of the state nature leaves it in, which begins the property; without which the common is of no use. And the taking of this or that part, does not depend on the express consent of all the commoners. Thus the grass my horse has bit; the turfs my servant has cut; and the ore I have digged in any place, where I have a right to them in common with others, become my property, without the assignation or consent of any body. The labour that was mine, removing them out of that common state they were in, hath fixed my property in them.

Perhaps Locke was a disinterested intellectual grappling with serious thoughts about freedom and property. Or perhaps he was a self-serving and hypocritical advocate for expropriating Native lands because he had significant investments in the English slave trade through the Royal African Company and the Bahama Adventureres Company, and was intimately involved with American colonialism. He even assisting in drafting the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, a document which stipulated “Every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves.” Much of his work served as convenient justifications for the rich to remain rich, no matter how little they actually worked.

In many cases, what people consider to be “laziness” has a lot to do with property and perspective. Throughout the history of capitalism, the corporate-controlled press has been relentless in demonizing labor unions for protecting “bad” workers—you see this in the stereotype of the “lazy” union worker. In Upton Sinclair’s frequently misunderstood socialist novel, The Jungle, he satirizes the propaganda of “lazy” union workers; his immigrant worker protagonist, Jurgis Rudkis, initially refuses to join the slaughterhouse workers’ strike because he assumed the other workers were “lazy.” By the end of the novel, Rudkis develops class consciousness as a socialist himself, and realizes his error. Strikes, especially sitdown strikes, can easily be interpreted as laziness—after all, they are a refusal to work. Certain famous photos may appear at first glance to depict “lazy” workers, when they are actually unionized workers going on strike to protest inhumane working conditions.

Millennials too are widely perceived as being “lazy,” “entitled,” and “spoiled.” An entire cottage industry has sprouted up around blaming young people for failing to buy enough consumer products. For the first time in American history, millennials are doing worse than their parents’ generation, despite multiple studies demonstrating that millennials actually work very hard. Hard work has not resulted in the rewards promised by capitalism: American millennials are more likely to identify as “working class” than any other generation.

Research shows that when millennials are actually asked what they want from work, they are more likely to want perfectly reasonable and good things that everyone else should want; Gallup found that Millennials want “good jobs” instead of just any job, more time to spend with their family, and that they prefer conversations and coaching instead of soulless annual reviews and bosses. All of these findings seem to indicate that Millennials desire “good jobs” not because they are especially “spoiled” or “entitled,” but because they are more class-conscious than previous generations due to deteriorating economic conditions for young people.

So perhaps the next time one finds articles describing why many millennials are “can’t last 90 days at work,” leave work for “mental health” reasons or why they switch jobs every two years, one can interpret these findings not as an example of generational sloth, but as an example of psychological struggle in the face of rampant inequality, and/or passive resistance to increasing corporate exploitation.

So accusations of laziness aren’t leveled at young people solely because of typical generational warfare; Millennials are called lazy because capitalism is failing, and young people are suffering the brunt of the failure.

The widespread belief that the rich are rich because they work hard, and that the poor are poor because they are lazy and refuse to “pull themselves up by their own bootstraps,” are, like the concepts of meritocracy and the “unworthy” or “undeserving” poor, very old ideas, conveniently resurrected whenever necessary to justify suffering. According to this belief—aided by an abundance of perseverance porn—there is no excuse for people who refuse to walk 15 miles to work everyday, or for the people who refuse to follow the example of “inspiring” kids who continue to work at fast food jobs with an arm sling and neck brace after a car accident, because, after all, if these hard-working individuals can do it, everyone else must simply be lazy. Instead of questioning why we lack adequate public transportation or paid medical leave, we are left with poor-shaming anecdotes that should “motivate” us all to work harder.

Aside from the absurdity of knowing that the phrase “pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps” was originally intended to prove the absurdity of succeeding without outside help (because the very act is literally impossible to perform), the continued irony of rich people who don’t work accusing the working poor of being “lazy” shouldn’t be lost on us.

It’s true that there are many rich people who work a lot, but they are not rich because they work hard. They’re rich because a capitalist society heavily rewards those who have a lot of investments. Capitalists are quite literally people who receive money from owning a lot of investments, rather than working for every dollar like everyone else. This is why there are obscene scenarios where someone like George Soros can receive $1 billion in a single day for betting against the pound, and why billionaires like Bill Gates amass fortunes from arbitrary patent and copyright protections rather than their own hard work. Nobody “earns” a billion dollar fortune. And the bootstrapping myth only perpetuates the absurd pattern where the most victimized and hardworking people are accused of laziness by those who don’t really work. The philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote a cheeky essay called “In Praise of Idleness” criticizing the hypocrisy of the idle rich, while touting the benefits of a bit more idleness for everyone else:

There are men who, through ownership of land, are able to make others pay for the privilege of being allowed to exist and to work. These landowners are idle, and I might therefore be expected to praise them. Unfortunately, their idleness is only rendered possible by the industry of others; indeed their desire for comfortable idleness is historically the source of the whole gospel of work. The last thing they have ever wished is that others should follow their example.

Notice how accusations of laziness are always directed in one direction by those with the most power and ownership of the media landscape to those with the least. When corporations (who are legally considered persons) refuse to provide job training to entry-level employees to cut costs while professional expectations for new college graduates are higher than ever, the corporate entities are not accused of being “lazy.” When corporations continually push costs onto consumers by fooling them into working harder to clean and recycle plastics that shouldn’t have been produced in the first place, or making consumers go through the work of dealing with automated call systems to avoid the expense of hiring more expensive representatives, they are never accused of being “lazy” or refusing to do the work.

So when such blatant double standards are made clear, what exactly is the problem with laziness? Socialists shouldn’t shy away from the fact that a lot of the policies they champion would save people from pointless work, freeing up their time to do other things. In fact, making people’s lives as easy as possible is the point of a lot of the policies socialists favor. Universal programs don’t just provide critical benefits to everyone: By not requiring the heinous bureaucracy of means-testing, you don’t have to fill out any paperwork. You just receive the same human benefits as everyone else by virtue of being alive, without having to lift a finger at all.

Imagine a world where instead of filling out annoying FAFSA forms to go to college, higher education is a public good available to everyone, no matter how rich or poor they are. Imagine that instead of filling out Elizabeth Warren’s stupid paperwork to qualify for having some of our debts cancelled, the government automatically cancels all our debt without us having to do anything. Imagine that instead of undergoing asinine and incredibly harmful “step therapy” or “fail first” protocols required by bloodsucking health insurance companies, your doctor simply prescribes the treatment they think is best for you. Imagine that instead of registering to vote and rushing to the polls before or after work, you’re registered automatically when you turn 18. Imagine that Election Day is a national holiday, in which we all go vote and then sit on our asses the rest of the day, and maybe have a picnic.

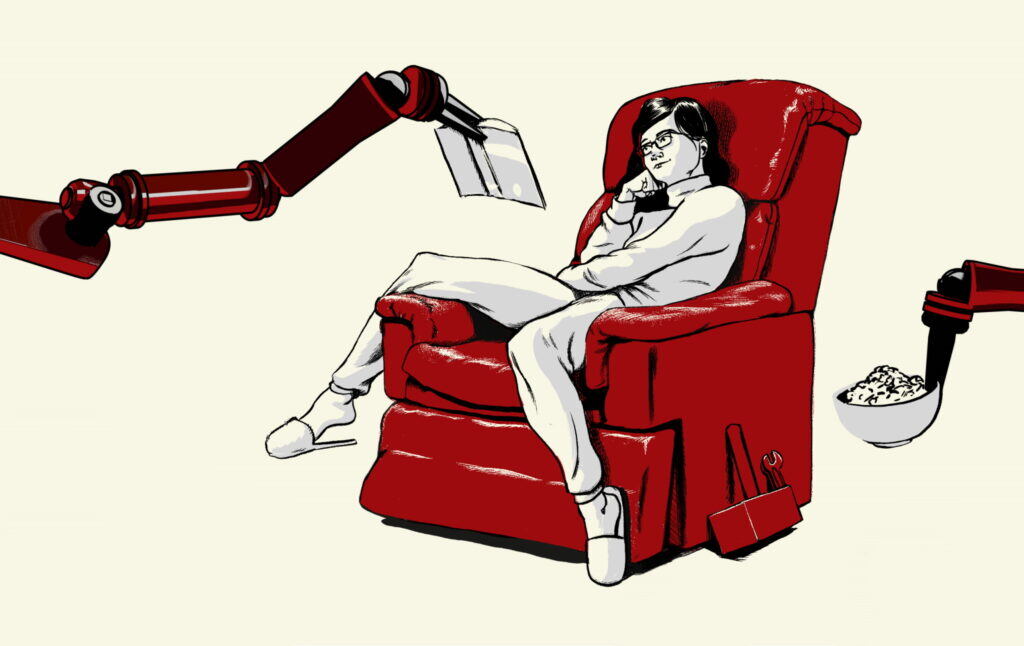

Imagining this future may be difficult, especially since we’re in the midst of a climate crisis that’s projected to get much worse. But this could also be a golden opportunity to demand less work. Research shows that one way to lower everyone’s carbon footprint is simply to have everyone chill out more by working less. Not all types of work need to be saved, and our livelihoods don’t have to depend on wage-slavery or planet-killing energy extraction. Socialists shouldn’t be embarrassed to admit that our ideal fantasy of fully automated luxury gay space communism would resemble a futuristic Garden of Eden where we’re free to laze around or do whatever we want, while solar-powered machines do all or most of the necessary labor.

Socialists and labor unions were the ones who rallied behind the “Eight hours labor, eight hours recreation, eight hours rest” slogan to win the 40 hour workweek from idle capitalists who wanted no upper limit to the amount of labor they demanded from factory workers, and there’s no reason we can’t be at the forefront of a movement to demand less work for all again. It might be easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine capitalists giving up their profits to sustain a shorter workweek, but it’s happened before. When people attack socialists for wanting an easy world that encourages laziness, we shouldn’t hesitate to agree. We should instead ask: “What’s wrong with laziness?”