Up until the end of last year, I was one of the last 1 percent or so of the population to stubbornly resist getting a smartphone. My reasoning, which turned out to be impeccable, was that if I had one I would constantly be distracted by the internet, because I am a person of poor self-discipline. Having a useless flip-phone that could offer no distractions would encourage me to look at the world, to find my way by asking directions. (It is also very satisfying to slam shut after an angry phone call.)

The theory worked, in a sense. I have a much better sense of direction than some of my friends, in part because when I get to a city, I have to try to understand its geography in order to navigate my way around it. But after spending one too many times phoning someone to try to get them to look up the number of a local taxi company, I gave in and got the infamous device that conservatives use to label socialists hypocrites.

One of the nice things about coming upon everything 10 years later than everybody else is that you get to be fascinated by things that everyone else takes for granted. The phone can identify music playing in the background! It can take a picture of a room and tell me the paint colors to buy if I want to replicate it! It can give me access to all of world literature, every song, and the television! It can translate street signs from foreign languages! And, best of all, it can take gorgeous pictures.

The flip phone camera was unbelievably bad. It might as well not have existed. The pictures looked like they had been “taken with a potato,” as anyone I ever sent one to always informed me. The iPhone camera, on the other hand, produces stunning photographs with ease. And all of a sudden, I have gone from someone who never takes pictures to someone who takes them constantly. And I have become far more enchanted by ordinary things.

Let’s distinguish between taking pictures and taking photographs. A photographer is a professional, or a skilled amateur. Photography takes work. A picture-taker is just someone who wants snapshots of things. I am not a photographer. I just take pictures.

I do not take pictures of just anything. But my philosophy is not very complex: I like pretty things, or things that look a little odd, or things that are striking and I want to remember. The first two pictures I took that made me realize I liked taking pictures were these:

The first is a hat covered in plastic king cake babies. A friend of mine was wearing it on Mardi Gras. The second is a croissant and a latte I had in New York City. When I saw my friend’s hat, I realized that it was indescribable. It needed a photo. And so one was taken. And when I was served my coffee and croissant, I said to myself: “This is the sort of food one can take a pretentious Instagram photo of.” And so I fiddled with the filters and arranged everything carefully so as to look unarranged, and took my “Oh, just visiting #NYC and reading high-class leftist literature” photo. I saw immediately why people do this.

I realize that people have been taking pictures of things for nearly 200 years, and that they have had reasons for doing it, and that social media is flooded with people’s endless photos of things, but I wasn’t taking pictures before, because I didn’t see the purpose. I am a camera already. I look at stuff. If it is memorable, I remember it. If it is forgettable, it is forgotten. I could not see why, when people visited places, they took pictures of them. You are looking at it already.

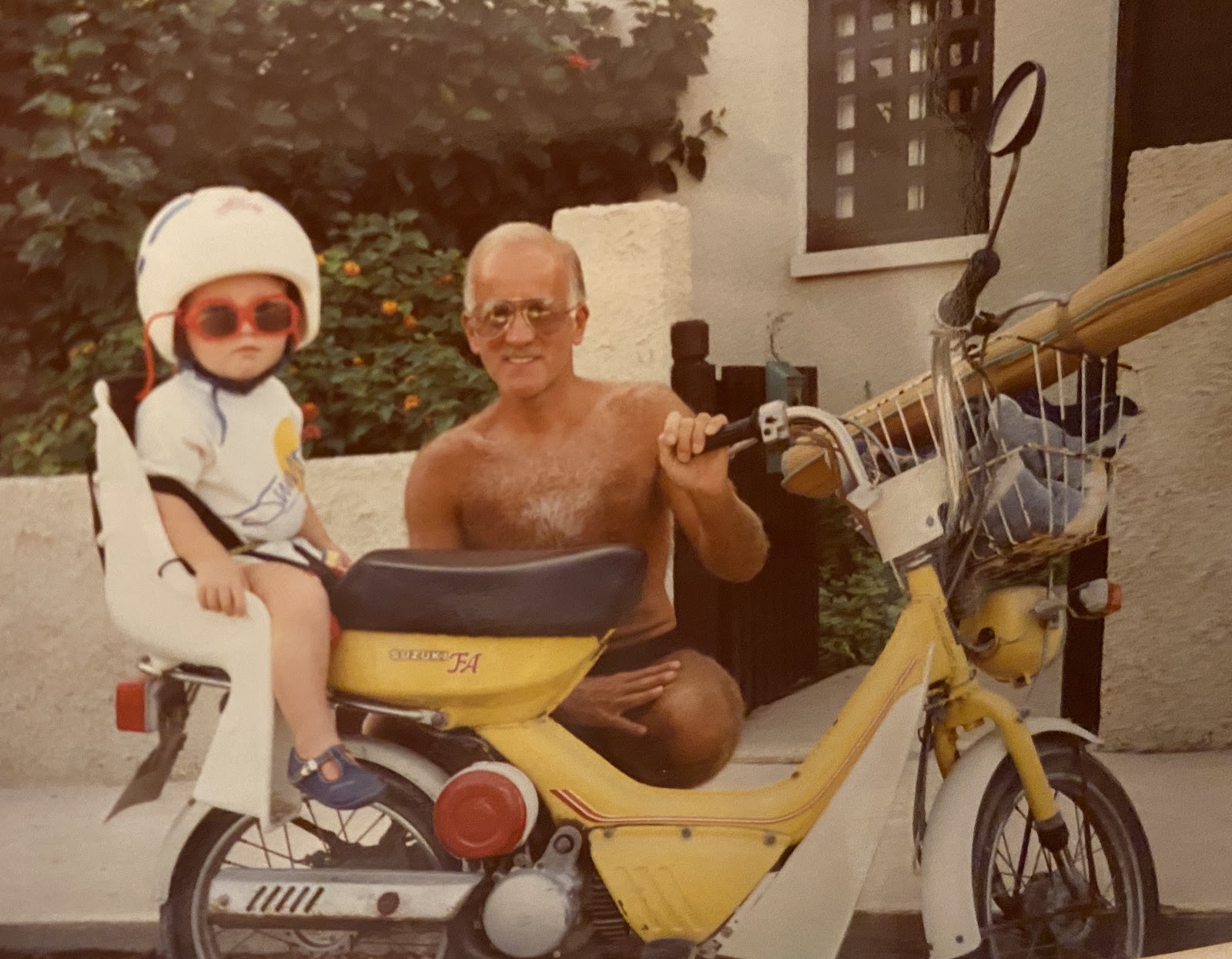

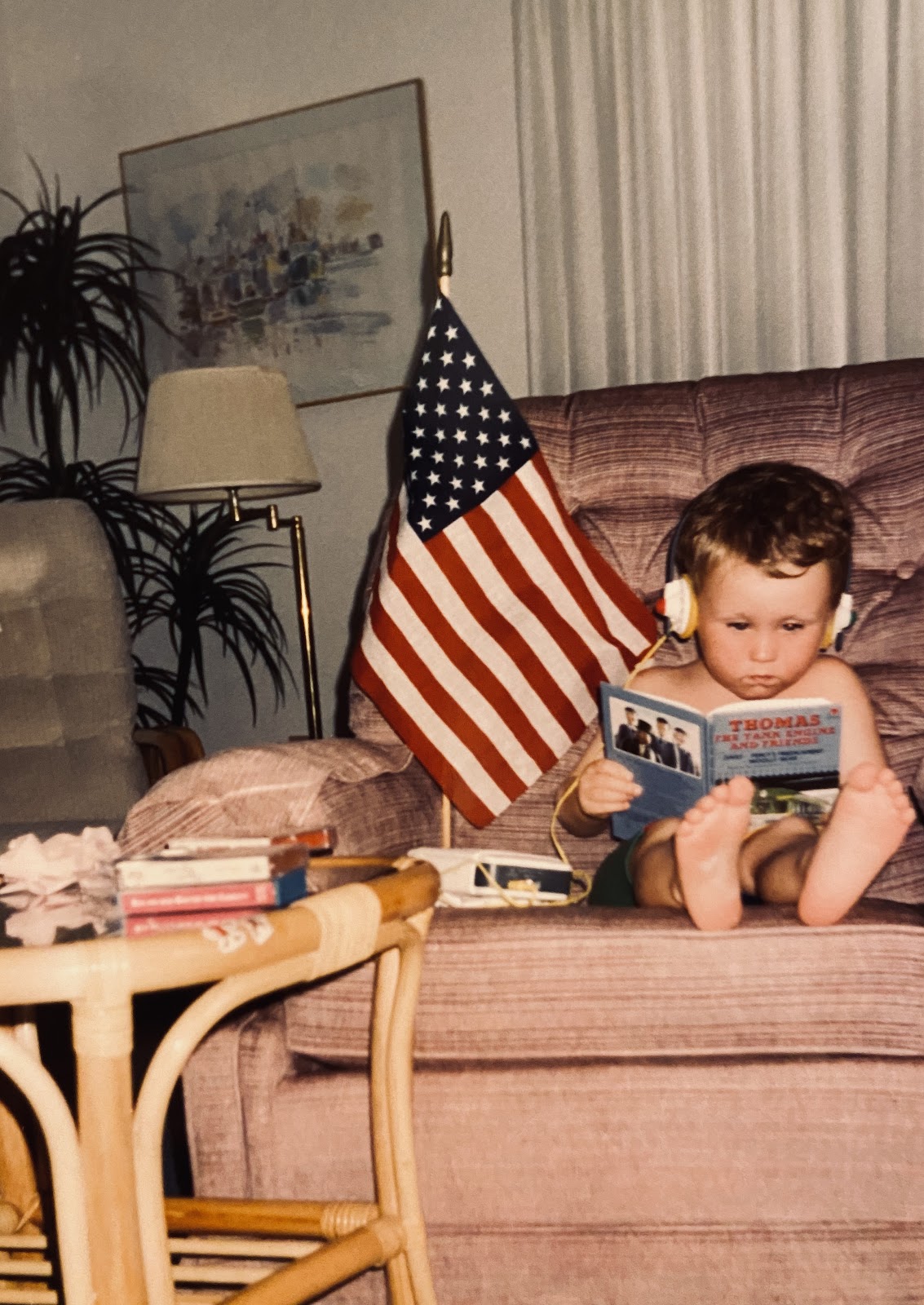

But, idiot that I am, I didn’t think: Well, but perhaps a photo will work in concert with your memory. It didn’t occur to me that taking a picture of an especially tasty croissant, or a coffee on an especially attractive old plate, will better help me remember how tasty the croissant was. But as I started taking pictures of the nice things I see, I realized I loved looking through them. I also started diving into old family albums and poring over everything. I’d never cared to take out the albums before, now I wanted to look back through my whole childhood, remember what color every shirt was, how every carpet felt. I became lost in nostalgia. Nostalgia is good. False nostalgia for an imaginary past is bad, but real nostalgia is an important part of being a human and looking back over your life.

I became sympathetic to tourists. When I went to Barcelona, I visited the things tourists visit, and I took pictures of them just as they were taking pictures of them. And you might think: Well, surely there are enough pictures of the Sagrada Familia and the Park Guell at this point. If you want to look at it later, you can just look it up on Flickr and see much better photos taken by professionals.

Ah, but these were my photos of the Sagrada Familia and the Park Guell. They show how these things looked through my own eyes. They are not pictures of tourist attractions so much as they are little bits of my life that I have managed to preserve for myself. Who cares if these things have been captured a billion times? Not through my eyes they haven’t.

I say I’m a picture-taker rather than a photographer, but you can see that these are very pretty pictures. That is, in large part, because iPhones are just an incredibly sophisticated technology that does a ton of the work that for many years a trained photographer would have had to do in order to get something to look nice, so that any picture-taker can now be a photographer. It’s also the case, though, that I think about how my pictures look and not just what I’m taking a picture of. And once you start thinking that way, your pictures become very different.

In fact, in some ways that is the difference between an ordinary snapshot and a photograph: The photograph has had time and effort put into thinking about how it looks. What’s in the shot, what’s not? What mood do I want to convey? How should objects be related to one another in space within the photograph? The smartphone gives you a dozen different settings you can fiddle with, and I like to spend ages seeing if amping up the shadows will give a picture the kind of sense of gloom I’d like to capture. When you do this, you’re in many ways trying to get a photo that will accurately reflect the experience you had looking at the thing. When I took photos of Mardi Gras for this magazine a few years back, with a much worse camera, I realized that they captured almost none of the spirit of the event. They were almost worthless in conveying how it felt to be there. At this year’s Mardi Gras, I still didn’t get any photos that adequately convey the Mardi Gras Magic. But I do think conscientiously about how to get a picture that has, to the extent possible, the flavor of reality. In the photo from Park Guell, above, everything is very deliberate: I wanted to get the glow of the sunshine on the tree and the balcony in the same picture. I wanted the picture to be half of the house and half of the park. I wanted it to have warmth, so I futzed with the filters. I carefully made sure no other buildings were prominent in the shot, so I could show the land stretching off in the distance. And I wanted a sliver of sky, mostly obscured by trees. These were deliberate decisions to make the picture have the right feeling, the feeling I had standing there.

By doing all this, in some ways one might say you are actually creating a lie. Because you’re only taking a very select bit of reality and choosing to exclude anything that doesn’t look nice. You’re changing the colors to match your emotions rather than the “actual” world. I take 10 pictures for every single one I’m willing to show to people publicly, and sometimes take 30 shots of the same thing before every element looks right.

My favorite photo I’ve ever seen is this one, by Joel Sternfeld:

As you can see, it depicts a firefighter shopping for pumpkins while a house fire rages in the background. The photo is a lie, although Sternfeld did not stage it. The house is one firefighters practice on, not an actual emergency that the pumpkin firefighter (who is on break) is choosing to ignore. Sternfeld got very lucky to witness this and be ready with his camera, but he wasn’t just lucky, because it takes skill to notice these things and to frame the juxtaposition of the two events in the shot exactly correctly. Sternfeld is a great photographer who happened upon a perfect moment and knew how to take advantage of it.

Perhaps I have indeed slipped, then, from being a mere picture-taker into a photographer, because I do love thinking about how the picture looks and not just the object being captured. But the purpose of what I am doing remains very humble: I just want to be able to remember how things were. I don’t need to get a perfect photo of a flower, but I do want an image that shows, as best as it can possibly be made to, what the flower seemed like through my eyes.

Consider this picture:

This is in a park near my parents’ house in Sarasota, Florida. I have always loved that there are old-fashioned lampposts in the middle of a completely overgrown jungle. And I wanted a picture that would convey the way this park makes me think of a tropical Narnia. But you can’t take a picture of the lamp post from just any angle, because this shot is something of a lie. The lamp post isn’t in the middle of nowhere, it’s by a well-traveled, well-paved path, and the jungle only looks like this from one particular point of view. If you turned around, it would look like you were on the border of a suburban neighborhood, which you are.

The iPhone has an option in the photo editor called “vivid,” and I like to press it, because instantly all of the colors become brighter and the world becomes a more brilliant and exciting place to look at. In this instance, only the “vivid” filter shows how lush and wet and alive and bright green this little patch of wilderness in the middle of civilization seems when you are standing looking directly at it and ignoring everything to your left and right.

Most of the pictures I take are of plants and buildings. Plants are inherently beautiful, and while I am not an architect, I do have strong opinions about which buildings are the Good Buildings. If you find yourself near some good plants and a good building, it doesn’t matter if you’re more picture-taker than photographer. As long as you’ve got the Fancy Phone Camera, and are willing to play around with the angle you shoot from and the filters, the picturesque world around you will do almost all of the work.

But there are still precise conscientious decisions to be made. In this one I wanted to get pieces of all four rooftops. I wanted the shadows on the pavement. I wanted the yellow door almost in the exact center, both horizontally and vertically. I wanted warmth, because yellow. I do not know why I wanted these things. But I did.

The relationships between physical objects matter, and when you start taking pictures, you begin to develop an eye for when two things look interesting next to one another. In this picture, the whiteness of the car and the whiteness of the building were striking to me:

But I also wanted to get the cracks in the pavement. I took a few photos of just the car and the townhouse, before realizing that what it needed was more pavement.

Old cars are rarer and rarer nowadays. But where there is an old car, there is usually a nice picture to be taken:

Once again, the relationships between the things are what interests me. In this next photo, I wanted to show the bank building towering over the man, and to make it shadowy and menacing.

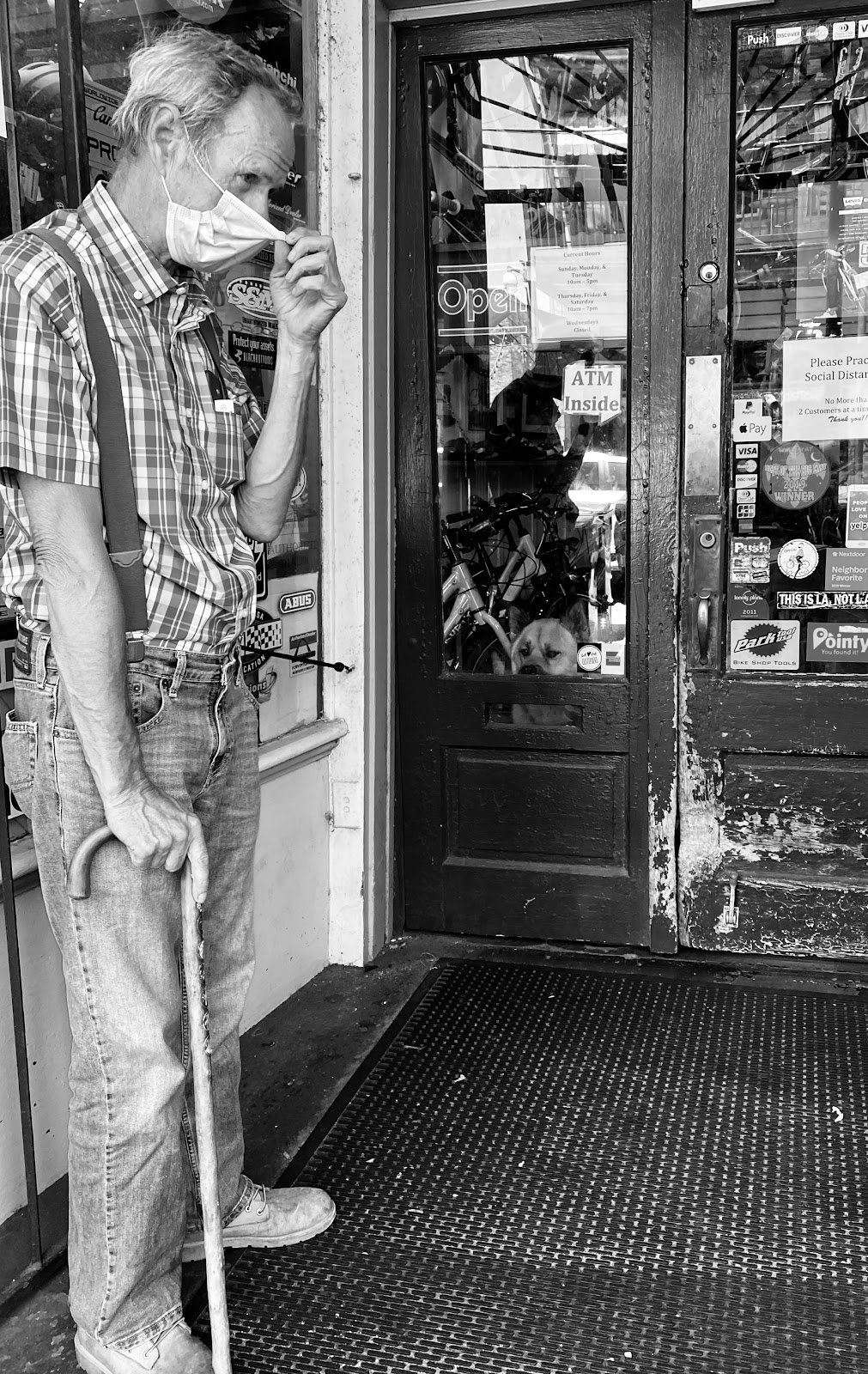

I don’t usually take pictures of people, because most of the time (unless they are far away specks) you should ask their permission, and I feel like a creep if I ask people to let me take their picture and am unable to give a reason why. (“Oh, just personal use.”) If I was the Humans Of New York Guy, I could tell them it was for my popular blog showcasing ordinary folks doing ordinary things. But I do not have such a blog and I do not feel like inventing a fictitious one for the purpose of tricking strangers into letting me photograph them. So I stick to buildings. Or plants. Or plants growing on buildings. But occasionally, you see a person so memorable you want a picture:

Here is an old man standing in front of a bicycle shop, with a dog peering out of the door. I only occasionally turn my pictures black-and-white, because there is something that feels very pretentious about it. Black-and-white really does cry out “I, sir, am a Photograph, not a mere picture.” I think the use of black and white by default is a little arty-farty. But sometimes you flip it into black-and-white and it just looks better. This man had bright red suspenders and a blue shirt. The wall was yellow and the door was green. It was a very colorful picture. But in this case, the colors detracted from what I wanted to remember. I wanted to remember the man tugging on his mask to get a bit more air. I wanted to remember the cane. Not the bright red suspenders.

If you want a really pretentious black-and-white picture, how about this one:

But again, in my defense, I am not trying to Say anything. I just liked how long the shadows were coming through the fence. I liked how all the lines looked, the sharp contrast. It reminds me vaguely of a prison, with a guard tower and a searchlight, even though it is a fence around a garden.

Nighttime is a wonderful time to take pictures. Of course, pre-smartphone, everything I took was just pitch black and unrecognizable. But if you find places where there are patches of light, your pictures can make you feel a bit like you’ve, I don’t know, found the spots of humanity in the blank void of space.

Here are two pictures from Royal Street in the French Quarter on a Friday night. The first shows the security guard at the convenience store joshing with some young men on their way out. The second shows tourists standing outside the Hotel Monteleone deliberating about where to go. What do I like most about these pictures? In the first one, the green light. In the second one, the golden interior of the hotel.

When you are walking around, you will see things on the street, and sometimes those things will be worth remembering. I keep an eye out. Sometimes, I realize something was interesting after I have passed by, and will rush back. I didn’t realize at first that a pile of books dumped next to a fire hydrant was interesting. “Oh. Books.” my mind said. But a block later I went “Oh! Books!” and returned with the phone out.

Chaotic pictures with a million things in them can be wonderful. Sometimes you go in a shop and it is just crammed with items. Good time for a picture. These are from a fancy antiques store and a bike store. I am something of a “maximalist,” meaning I delight in things that are messy and complicated and much-too-much.

Of course, anyone who wants to wander around taking pictures of pretty things is at a significant advantage in New Orleans, where the amount of everyday beauty and eccentricity is higher than any other city in America. It can feel like cheating, actually, when people tell you they like your pictures, because around here you can just point a camera at a random thing and you’ve got a pretty good chance of taking a cool picture. But when I’m visiting my parents in Florida I get neat pictures, too.

In the film Ghost World, main character Enid takes an art class that heavily emphasizes conceptual art. The things students make are expected to mean something. Enid’s teacher comes across her drawing a portrait of Don Knotts, the bug-eyed actor from The Andy Griffith Show and The Incredible Mr. Limpet. The teacher asks Enid why she is drawing Don Knotts. “I just like Don Knotts,” Enid replies. This is seen as a very stupid answer.

It isn’t, of course. We don’t need to be able to explain things. I am not sure why I liked the juxtaposition of this skull and the bit of ornamentation:

Nor am I sure why I wanted to take this photo of three men in masks driving a John Deere cart in front of a bar:

I thought you might like to see some of my pictures, for a couple of reasons. First, I think many of them are just nice to look at, and I try to take pictures that have a certain warmth to them. So maybe you’ll enjoy them aesthetically. But I also want you to know that you do not have to be a Photographer to take pictures. The phones are good enough now to where the technical skill required for good pictures is almost negligible. What matters is your creativity, which depends on your ability to look at things and select them and arrange them carefully. Learning to take pictures is a lot like picking up graphic design, in that you start noticing things you never noticed before. And, also as with graphic design, as you start to do it you really start to respect the professionals more, because you realize just how much work it takes to get something to look just right.

But you don’t even have to be especially creative to enjoy taking pictures for the purposes of having some pleasant things to remember. Many of my pictures are really quite boring. A window. A butterfly. A bicycle. Some aren’t even taken in interesting ways: I just want a picture of the butterfly, I don’t care how the butterfly is framed in the picture. What matters to me is not that the pictures are professional but that they are purposeful, that they are not just a thing you think you ought to take a picture of (because it is The Kind Of Thing People Take Pictures Of) but that you have some reason. It doesn’t have to have articulable meaning, but it should be something you want to return to, to look at and enjoy later on.

Taking pictures is a miraculous kind of act. It really is like managing to capture and bottle a piece of the world. I used to take it for granted. Not anymore. Now I look at everything I pass by and ask myself: “Is this a picture worth keeping?” And a few times a day, I find that the answer is yes.