Capitalism As Religion

On Eugene McCarraher’s “The Enchantments of Mammon: How Capitalism Became the Religion of Modernity,” a fascinating study of the ways in which capitalism, despite its purported scientific rationality, is really a perverse kind of religion.

One of the few things that socialists and capitalists largely agree on is that the development of capitalism was part of a larger shift in the social and intellectual worlds of Europe, and that this enormous shift was characterized by an increased reliance on human reason and a decrease in religious superstition. This is what the sociologist Max Weber called the “disenchantment” of the world: we no longer view the world as pervaded with divinity or magic, because industrialization and the development of capitalism have stripped these enchantments away. Socialists and capitalists will both, then, be equally surprised to learn from Eugene McCarraher that this story is wildly incorrect, and that we have never lived in a disenchanted world. Rather, the enchantment that supposedly characterized the Middle Ages has persisted uninterrupted into modernity, but has taken different forms, and our capitalist world is alive with tutelary spirits, sacramental rites, and visions of eternal beatitude.

McCarraher, a professor of history at Villanova University, makes this argument in a brick of a book entitled The Enchantments of Mammon: How Capitalism Became the Religion of Modernity. The text itself takes up nearly 700 pages, with a further 106 pages of endnotes, and the pages themselves (though printed in a readable typeface) are dense with information and narrative. It’s the product of nearly twenty years of work, epitomizing the ethos of craftsmanship preached by William Morris, John Ruskin, Dorothy Day, and other figures of Romantic resistance to whom McCarraher introduces his readers. With this architectural attention to structure and prose style, McCarraher’s massive book is no chore at all but a genuine delight to read.

Along with his intellectual-historical argument, McCarraher aims to introduce his readers to another way of looking at social and economic history, one that goes beyond bare material relationships and incorporates the spiritual dimension of our experience. This is not a religious view in the sense of being tied to the dogma of any particular religion, but it’s rooted in McCarraher’s own Roman Catholic background, and the most consistent term that he uses for it is “sacramental.” In Catholic theology, the sacraments are the visible means through which humanity participates in divinity: the words and actions that both signify and dispense God’s grace to the faithful. When a sick person is anointed with oil and particular prayers are said over them, the anointing and the prayers signify God’s grace but also, according to Catholic doctrine, actually make it present. McCarraher’s argument seeks to expose the sacramental logic of capitalism—the ways in which capitalism sets up its own gods and ordains rites for the dispensation of capitalist grace (that is, money). He argues that:

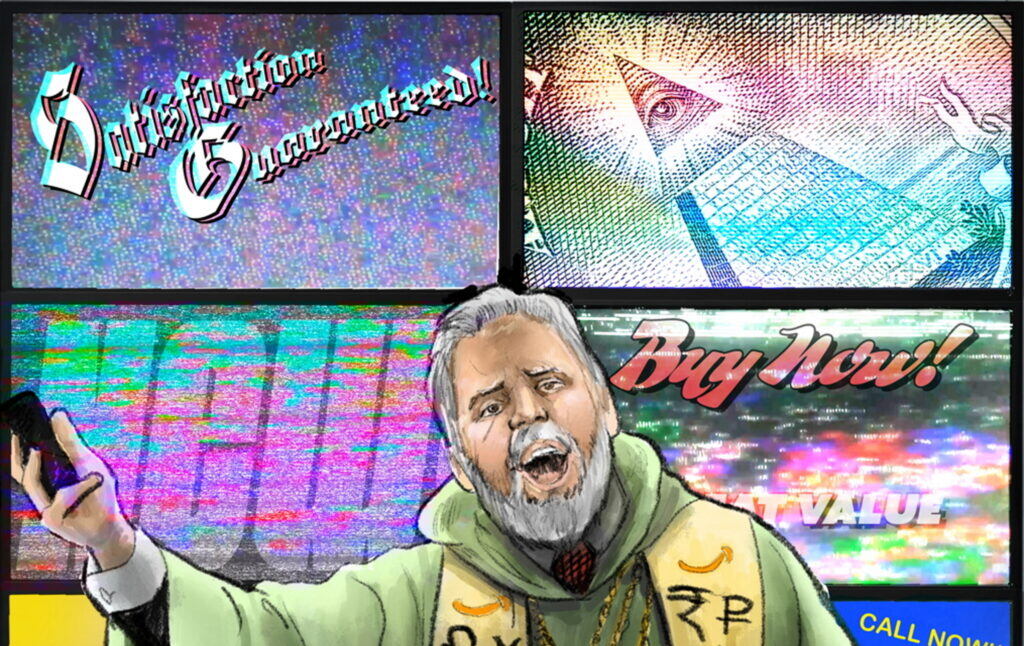

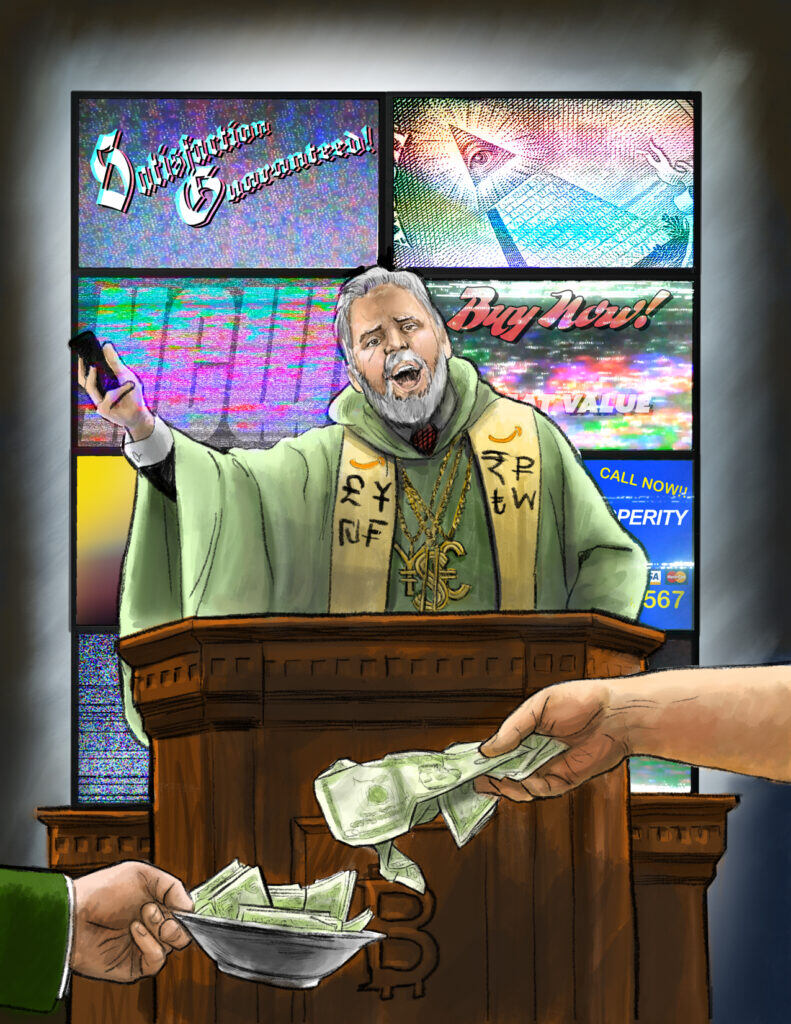

…capitalism is a form of enchantment—perhaps better, a misenchantment, a parody or perversion of our longing for a sacramental way of being in the world. Its animating spirit is money. Its theology, philosophy, and cosmology have been otherwise known as “economics.” Its sacramentals consist of fetishized commodities and technologies—the material culture of production and consumption. Its moral and liturgical codes are contained in management theory and business journalism. Its clerisy is a corporate intelligentsia of economists, executives, managers, and business writers, a stratum akin to Aztec priests, medieval scholastics, and Chinese mandarins. Its iconography consists of advertising, public relations, marketing, and product design. Its beatific vision of eschatological destiny is the global imperium of capital, a heavenly city of business with incessantly expanding production, trade, and consumption. And its gospel has been that of “Mammonism,” the attribution of ontological power to money and of existential sublimity to its possessors.

This is strong stuff, and it’s difficult not to buy into McCarraher’s argument from the very beginning, purely based on the rhetorical, intellectual, and moral force with which he states it. I admit up front that I am well positioned to accept most of what he says: like him I am both a Catholic and a socialist, and like him I find it difficult to tell where one of those ends and the other begins. A more skeptical reader might, however, argue that this all sounds very good as a metaphor, but doesn’t have much descriptive value for the ways in which capitalism has developed and continues to function. This is where the historical portion of McCarraher’s argument comes in, and it’s this history that occupies the vast majority of the book.

McCarraher begins with the medieval period, “in which the material world and social life could reflect and convey divine grace and power. For serf, lord, merchant, and artisan as for pope, archbishop, and scholastic philosopher, all of life was sacramental, pervaded by the presence of the triune God.” In more general terms, the world and everything in it was considered to partake of divinity, and this included human beings, animals, and all natural things. As a result, there was an order to the world and a set of expectations governing how human beings ought to relate to the rest of creation. This was not a wholly benign order, as “the crown of the sacraments could be used to sanction the most oppressive power,” but it rested fundamentally on the idea that human beings are stewards of the world, not its owners. In this view, though humanity had fallen, the world was fundamentally a place of goodness and abundance, a gift from God to all of us, and this view was reflected in a wildly different notion of what “property” was and what one could do with it. The more conventional historical picture bears McCarraher out on this point. To take an example from English history, most feudal manors included common land on which tenant farmers had the right to pasture animals. The lord who held title to the land in the manor had no right to interfere with this use, nor did he have the right to kick tenants off his land. One of the marks of the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in England was the widespread enclosure of this common land, which contemporaries like Sir Thomas More saw as a kind of theft, since it transformed a public resource into a commodity that could be bought or sold.

But even this privatization was not, at first, absolute. In England and France, for example, by ancient custom derived from Mosaic Law, any grain or fruit that fell to the ground during harvest—or was left on the stalk or vine—was the property of the poor, who had the legally-protected right to come into the fields and recover this leftover food. This practice was known as “gleaning.” This right persisted in parts of England well into modernity, until it was ended for good by the House of Lords in a decision on a lawsuit—Steel v. Houghton (1788)—a case that is considered by legal and political historians to mark the beginning of the modern understanding of absolute property rights. After Steel, a property owner’s rights were absolute, and property was fully transformed from a form of stewardship oriented toward the common good into an atomized possession for the sole benefit of an owner, open to the world only to the extent that its owner permitted.

This was the beginning, argues McCarraher, not of a rationalization or secularization of the world, but of a widespread remaking of the image of God and therefore of the sacramental order of the world. John Locke epitomized this tendency when he characterized human beings as “[God’s] property, whose workmanship they are,” bound “not to quit [their] station willfully,” exchanging God the free creator who creates purely out of love for God the petty foreman who has a right to extract value from his creation. This is the other major argument that runs through McCarraher’s book: capitalism, having unconsciously retained the idea that humanity bears the image of God, has continually endeavored to replace God with lesser things and therefore to remake humanity in the image of these idols. This replacement is called “rational” because it stops using the term “God,” even though these replacements serve more or less identical functions. Think, for example, of Adam Smith’s “invisible hand,” originally deployed as a metaphor but later characterized by Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson as a “mystical principle” in his 1948 economics textbook, converting a metaphor for the social forces of markets into an incomprehensible mystery of the cosmic order. In mistaking the laws of capital accumulation for fundamental laws of the world, we mistake something temporary and mutable for something eternal and unchanging, and set up for ourselves the impossible task of conforming our lives to these “objective” laws, rather than realizing that we can and should re-shape these temporary laws and institutions in the image of the basic and unchanging needs of human beings.

The ways in which we have mistaken the temporary for the permanent, and the profane for the sacred, and the ways in which some people have resisted this misenchantment form the narrative line of McCarraher’s book. The Puritans arrived in America “bearing belief in a world of wonders” and also believing in a secret knowledge by which nature could be made to yield its fruits. This was not, incidentally, the knowledge of how to grow crops in New England (for that, they needed considerable help from the Native community) but the pseudoscience of alchemy. John Winthrop, son of that John Winthrop who exhorted the Puritans to be a “city on a hill,” was not only a Puritan Christian but also an alchemist who viewed alchemy “at once [as] religious quest, scientific project, and business enterprise.” This alchemical sensibility would substantially influence the burgeoning American theological-economic imagination. For Christian alchemists, those who worked diligently to uncover the secrets of God’s creation and applied them with faithful hearts could work wonders, culminating in the transformation of base metal into pure gold. This aligned well with the covenant theology that governed the new Puritan communities, in which thriftiness, hard work, and faithfulness would bring prosperity and material wealth as “God’s benediction on the righteous, a reward from the Almighty to the archangels of improvement.” Already in early America we see wealth transformed from an accident of birth or chance into the visible sign of God’s favor, a halo for contemporary saints. The commercial market soon became identified fully with God’s providence, an identification most fully expressed by the contemporary proclamation of the “prosperity gospel,” in which God shows his perfect and boundless love for creation by letting some people drive a Mercedes.

One of the things that McCarraher leaves unexplained despite its importance—perhaps because he assumes a certain degree of religious literacy in the reader—is how the nebulous concept of “providence” lurks at the heart of so much Christian turning toward the worship of Mammon. It is perfectly true that, for Christians, God’s providence lies behind everything: it is God’s will that sustains all creation from moment to moment, and our very existence is a free outpouring of God’s love. In that sense, God lurks behind everything we do and is always at work in us, for even our freedom to do evil bespeaks the divine freedom in which we participate. It’s very easy, therefore, to make the small but critical jump from this broad understanding of providence and to trade divinity for divination—to miss the divine beauty imperfectly revealed by all things in favor of treating particular things (like a Mercedes) and circumstances (like being born wealthy) as the special barometers of God’s will. This is the particular heresy that, for McCarraher, unites all our varieties of capitalist misenchantment: we treat markets as omens of divine favor, entrepreneurs as God’s anointed, and economists as the prophets who reveal God’s will. Economists bring glad tidings that the GDP continues to rise, which is supposed to reassure us that despite widespread poverty, crushing debt, and children caged on our border, the talismanic power of rising numbers will somehow see us through.

What works against this false and heretical misenchantment is something that McCarraher dubs “Romanticism,” a name that he uses because he finds it most powerfully expressed among the poets and artisans closely associated with the Romantic movement. We often see the Romantics characterized as a kind of reactionary movement against the Enlightenment, a gang of literary types who resented “reason” and did a lot of drugs. This is not entirely a false characterization. “Yet Romantic writers of all kinds,” McCarraher says, “made clear that their nemesis was not reason but rather reason torn from the fabric of nature and humanity—a rupture that made a demon and idol of reason, a despoiled wreck of nature, and a beguiled slave of humanity.” The antidote to the Enlightenment worship of reason is not the total rejection of reason but its completion, its re-integration into the fullness of humanity, which the Romantics termed “imagination.” As McCarraher explains:

In the Romantic sensibility, imagination was not a talent for inspiring fantasy, but the most perspicuous form of vision—the ability to see what is really there, behind the illusion or obscurity produced by our will to dissect and dominate…For Romantics, imagination did not annul but rather completed rationality…Though warning of the brutality of instrumental reason—“our meddling intellect / Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things; / We murder to dissect”—Wordsworth described imagination as ‘Reason in her most exalted mood.’ Imagination is the ecstasy of reason.

The spirits who most powerfully articulate this “ecstasy of reason” in McCarraher’s account are those Romantics who looked to the medieval past for inspiration in building a communal future. First and chief among them is the art critic and social thinker John Ruskin, who praised medieval Gothic architecture for creating beautiful, monumental buildings that were simultaneously scaled to human use, and for involving whole communities in the creation of these buildings, while still providing opportunities within these projects for the individual expressions of particular artisans. Ruskin was also an outspoken critic of mechanization and industrialization, believing that it alienated people both from their work and from one another: he claimed it destroyed the intimate relationship between a craftsperson and their work, as well as the relationships between the craftspeople and those who bought and then used the objects that they made.

Ruskin’s disciple and intellectual heir was William Morris, who has garnered admiration in some of this magazine’s most controversial articles. Morris became enchanted by the Middle Ages during his undergraduate studies, but he was not some sort of reactionary monarchist pining for the boot of feudalism (you are thinking of Jacob Rees-Mogg). Quite the contrary: Morris’s medieval infatuation drove him to utopian dreaming of a world without private property, and this utopian vision led him to Marxism and political friendships with Friedrich Engels, Wilhelm Liebknecht, and Karl Kautsky as well as the anarchists Sergey Stepnyak-Kravchinsky and Piotr Kropotkin. Morris’s politics were always animated by a vision of work divorced from profit: one of the characters in his utopian novel News from Nowhere describes artisanal work as its own reward, “the reward of creation. The wages which God gets, as people might have said in time agone.”

This longing for creation without money is vital to understanding McCarraher’s variety of Christian socialism, which is rooted in the classical understanding of God’s free creation of the world. As Fr. Herbert McCabe, one of McCarraher’s most profound intellectual influences, puts it, “God’s creative act is an act of God’s poverty, for God gains nothing by it. God makes without becoming richer. His act of creation is purely and simply for the benefit of his creatures.” Insofar as we imitate this free giving of life, we become more Godlike and thus more like the people we ought to be. Here is where the Christian and secular socialist visions come together: for both camps, the central depravity of capitalism is that it represents a perversion of human nature, a rupture between how we ought to be and how we are forced to behave. We are social creatures who flourish in community with other people, and yet capitalism has made physical and emotional suffering into a precondition for living in any kind of community at all. It has alternately promised an idyllic automated Eden free of labor or a futuristic utopia of unimaginable abundance, but always delivers instead a Pandæmonium, an infernal city of strife in which the nature that draws us together pits us against one another.

Leftists are often skeptical of arguments about “human nature,” in large part because such arguments are so often deployed by libertarians and other right-wing types seeking to naturalize and justify the systems against which we struggle. Indeed, these arguments are often phrased in Darwinian terms, where “survival” and “progress” and “improvement” are imperatives whose demands flood our synapses and compel us to desire the ruin of our fellow person so that we might pick their bones. But the truth is that we do have basic human needs: for food and water, for shelter and warmth, for rest and play, for emotional and physical closeness with other human beings. McCarraher, rather than developing some grand unified theory of human nature based on shaky scientific foundations, simply asks us to consider these basic human needs as part of our nature, and their satisfaction as necessary for our flourishing. In doing this he employs a distinction originally made by Ruskin between “wealth” and “illth.” Ruskin sought to distinguish between two kinds of abundance and to avoid what he saw as a deep confusion about wealth. In Ruskin’s articulation, wealth is what helps us to do well by satisfying our actual needs: a warm bed, good healthy food, a comfortable chair, a well-kept public park, etc. Illth is wealth’s inverse—worldly prosperity that satisfies false needs and, in doing so, hurts rather than nourishes its possessor and their society (think of expensive “anti-aging” skin products or cheap plastic toys or SUVs). As McCarraher explains in an interview with The Nation, “The distinction is qualitative. Wealth and illth are relationships between the good and the character of the person.”

This opens up the ecological dimension of McCarraher’s argument: as the misenchantment of capitalism glorifies our instinct for domination, it beguiles us into seeing nature as mere grist for the manufacture of material excess, blinding us to the goodness and beauty of nature as it is. We do not see the “illth” caused by our lust for conquest, for more and better stuff. This is not an anarcho-primitivist argument: part of nature’s good is that it can satisfy our needs. But nature is good when used to satisfy our actual needs, not the misdirected desires that capitalist advertising seeks to cultivate. It turns out that disordered wants are not only the primary source of our current environmental catastrophe—in the United States we outright destroy 40 percent of the food we produce and drive cars that constitute nearly 20 percent of our CO2 emissions—but accelerating consumption itself forms the basis for the entirety of classical and contemporary economics. McCarraher is extremely clear on this point in the same interview quoted above:

As a Christian, I reject the two assumptions found in conventional economics: scarcity (to the contrary, God has created a world of abundance) and rational, self-seeking, utility-maximizing humanism (a competitive conception of human nature that I believe traduces our creation in the image and likeness of God). I think that one of the most important intellectual missions of our time is the construction of an economics with very different assumptions about the nature of humanity and the world.

If only we would properly order our desires, he argues, we would find that “abundance and peace are the true nature of things, not the scarcity and violence that leaven the cosmology of capitalist economics.”

It is this moral critique that prompts McCarraher’s searing excoriation of economics as it is currently practiced. He spares nothing, for he believes capitalist economics to be nothing less than the scripture and priesthood of a demonic power. I quote his indictment in full:

The grotesque ontology of scarcity and money, the tawdry humanism of acquisitiveness and conflict, the reduction of rationality to the mercenary principles of pecuniary reason—this ensemble of falsehoods that comprise the foundation of economics must be resisted and supplanted. Economics must be challenged, not only as a sanction for injustice but also as a specious portrayal of human beings and a fictional account of their history. As a legion of anthropologists and historians have repeatedly demonstrated, economics, in Graeber’s forthright dismissal, has “little to do with anything we observe when we examine how economic life is actually conducted.” From its historically illiterate “myth of barter” to its shabby and degrading claims about human nature, economics is not just a dismal but a fundamentally fraudulent science as well, akin, as Ruskin wrote in Unto This Last, to “alchemy, astrology, witchcraft, and other such popular creeds.”

The argument being made here and above is a subtle one using some of the technical terminology of philosophy and theology, so it demands a bit of exposition. McCarraher contends that for economics, scarcity is ontological—meaning that the field of economics considers scarcity a fundamental fact of existence. The first implicit rebuttal is that scarcity is instead contingent and historical: it is brought about at particular times by particular circumstances, but is not a fundamental condition of existence. Making this rebuttal is part of McCarraher’s goal in writing a historical work. The second point, which is no less important, is that obsession with scarcity is alien to our humanity: we are not, at a very basic level, wired to operate as maximizing hoarders of the finite substance of life, and this is a point on which academic anthropology and Christian anthropology concur. Academic anthropology has made extensive study of gift economies[1] since the 1925 publication of Marcel Mauss’s The Gift, and for the Christian anthropologists “the goal of mankind” is “real unity in love,” in the words of Fr. McCabe. The fact that we begin to operate very differently within capitalist society must lead to the conclusion that there is either something wrong with capitalism or something wrong with humanity. McCarraher takes the former view, while even liberals like Jane Goodall, who recently suggested that environmental problems are caused primarily by too many of us being alive, have shown their hands as partisans of the latter.

The charge of attempting to remake humanity usually emerges from the mouths and pens of the right, directed at the left: think of the numerous denunciations of “social engineering” that one sees in attacks on affirmative action or the teaching of minority perspectives on history. Spoken by the right, the charge is usually one of conspiracy—a sinister cabal of elites/liberals/socialists/Jews making plans in a back room to alter humanity for the worse. But McCarraher’s charge is not conspiratorial; rather, he contends, the global dominance of neoliberalism as a system has altered our way of thinking and living, adjusting us to “the delusion of democratic promise, the open secret of corporate plutocracy, the supersession of all cultural and political limits on the power and authority of money.” No development was more effective in bringing about this adjustment than the advent of mass automation, which was welcomed with the “elysian reveries of the corporate business intelligentsia” while “the fetish of technology diverted attention from its origins in capital’s need to achieve complete mastery of the production process.” The ultimate project of capitalist automation has been to remake labor in the image of machines, forcing workers to submit to more and more degrading conditions in a vain attempt to temporarily stave off the automation of their work. Automation has become a vision of the End Times, an eschatological horizon beyond which lies the full mechanization of humanity itself.

McCarraher draws on a lesser-known Kurt Vonnegut novel, Player Piano, to illustrate this point. The novel describes a futuristic community in which mechanization has consumed most of the labor: the scientists and engineers live in comfort, tending to the machinery of production, and most people live in wretched poverty, eking out what small living they can working in the factory. All of this is watched over and planned by a master computer network, whose dictates govern the scientists’ work. This scenario seemed fantastical in 1952, when Vonnegut published the novel, but we have seen it come to full fruition in the warehouses and distribution networks of Amazon. Presided over by a machine intelligence that no one, not even its programmers, fully understands, quotas are dictated and employees rewarded or punished depending on their ability to meet these quotas. McCarraher, occupied as he is with writing a history, has little to say about the Amazon algorithm, but after being immersed in his sacramental imagination, one sees the advent of such a thing as perhaps the purest contemporary expression of traffic with demons. Through arcane formulae, Amazon’s engineers have put the company under the power of an inhuman intelligence that feeds on our collective greed and nurtures it through the imposition of catastrophic deprivation and suffering upon the poor. And since this algorithm’s imperatives are a pure expression of capitalist production—get more goods to more people to make more money—it is hard not to conclude that capitalism is, itself, ultimately an infernal order, a perpetual con job in which both spiritual and worldly salvation are always just around the corner if only we will trade a little more misery, a little more blood, a few more lives. Perhaps the greatest beguilement of capitalist enchantment is this notion that we can purchase the paradise to come on contract: we know, or should know, what happens to those who make bargains with the Prince of Lies.

This seems like a deeply pessimistic view of our current trajectory, and from the perspective of history, it is. Our view of history itself is a construction of capitalist enchantment: it shows us the spectacle of conflict and violence and says that this scramble for acquisition is as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, unto the ages of ages. The theologian David Bentley Hart contends that “capitalism will not have exhausted its intrinsic energies until it has exhausted the world itself” and achieved “the total rendition of the last intractable residues of the intrinsically good into the impalpable Pythagorean eternity of market value. And any force,” he says, “capable of interrupting this process would have to come from beyond.” To see beyond is precisely what McCarraher’s Romantic imagination demands of us. Beneath the spectacle of avarice and violence lies the still more fundamental reality of grace, in which the world and everything in it is pure gift, with no price or condition attached. To see beyond history, then, is to come to know the world as a gift and receive it as such. To live this gratitude, in which everything is given and nothing is ours, is our only way out, and learning to live this gratitude in truth is the real discipline of revolution.

While The Enchantments of Mammon is an extraordinary book, I don’t think that it’s required reading, and readers who do not share McCarraher’s deep religious convictions may not find it as persuasive as I did. It also has notable blind spots: aside from a chapter on the religion of enslaved Black Americans and brief coverage of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s prophetic witness, McCarraher gives very little systemic coverage to the strains of anticapitalism that have run through the Black Church through its history. I will grant that this subject probably requires its own expertise, but McCarraher is plainly acquainted with some of the expert literature, and he ought, perhaps, to have directed curious readers more explicitly to those experts. But even with this gap in mind, it is difficult to characterize this book as anything but a masterpiece for its synthesis of intellectual history, anti-capitalist polemic, and Romantic imagination. There is a great deal to be gained from McCarraher’s arguments, even if you don’t find his worldview entirely persuasive. Whatever our religious commitments, or lack of them, the gift of being here at all is a marvel; we didn’t bring it about for ourselves, and it is outside our power to hoard it forever. To try to hoard life is to forsake our freedom to give it. As McCarraher concludes:

That new world has always been present; history has not deprived us of an abiding and infinitely generous divinity. We can reenter paradise—even if only incompletely—for paradise has always been around and in us, eagerly awaiting our coming to our senses, ready to embrace and nourish when we renounce our unbelief in the goodness of things. And we can do this in the midst of imperial decay and in the face of seemingly impossible odds. Knowing that the world has been and will always be charged with the grandeur of God, we can practice, in the twilight of a senescent empire, love’s radiant, unarmed, and penniless dominion.

[1]“Gift economy” is a broad term used to describe non-market societies or social relationships wherein goods or valuables are given rather than being bought with money or bartered for. Such relationships are widely attested in ancient literatures—the Iliad and the Mahābhārata are both rife with examples—and persist in, among other things, the potlatch ceremonies held by indigenous communities of the Pacific Northwest.