Dirty Tricks Of The Public Relations Industry

You might be under the impression that P.R. is a slimy industry. The truth is that it’s worse than you think.

The birth of the public relations industry was one of the most quietly calamitous events in American history. While much derided and downplayed—try finding a movie or TV show where P.R. professionals aren’t repugnant slimeballs—the industry has been a massively influential presence in our lives since the turn of the 20th century, shaping our thoughts and feelings in ways that have caused immense damage to our environment, our fellow humans, and ourselves. The world would be better off if it simply didn’t exist. But like many unscrupulous activities, P.R. is both extremely profitable and useful to the interests of the wealthy, and for that reason it’s grown and prospered.

The metastasis of the P.R. industry came thanks to a number of simple-yet-effective tricks (more on those later) that most of us would prefer to believe are too obvious to work. Yet more often than not they do work, which is why few people remember that Coca-Cola hired death squads to kill unionized workers in Colombia or that Chiquita bananas are the product of a century’s worth of ecological devastation and human rights abuses. Some (especially the victims’ families) haven’t forgotten, yet their cries for justice have been drowned out by the cheerful, relentless hum of these companies’ powerful P.R. machines. To paraphrase Bob Marley, you can’t fool all the people all the time—but it turns out you don’t have to.

All you need to do is persuade—or bore—a critical mass of people into swallowing your message. Few have ever been adept at this as Edward Bernays, widely regarded as the father of public relations (and modern propaganda). The nephew of Sigmund Freud, Bernays made his bones by helping to stir up public support for U.S. intervention in World War I, then parlayed that success into a long and lucrative career which included such accomplishments as convincing American women that cigarettes (which he dubbed “Torches of Freedom”) were empowering and good for their health, and convincing the CIA to overthrow the democratically-elected government of Guatemala on behalf of the United Fruit Company (which has since changed its name to Chiquita).

In his influential book Propaganda (1928), Bernays made a case for the “conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses.” According to Bernays, while some bad actors might seek to manipulate the public for the wrong reasons, “such organization and focusing are necessary to orderly life.” He laid out a vision of the world that is chillingly familiar today: “We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.” In his view this wasn’t necessarily a bad thing, since it was people like him doing most of the governing, molding, forming, and suggesting.

Modern P.R. specialists are both strongly influenced by Bernays’ work and, in some cases, alarmed by its implications. Take Andrew Mckenzie, who penned an article for the International Public Relations Association (IPRA) that urged P.R. pros to be “the conscience of an organization,” and to insist that harmful actions “cannot be reframed or spun,” since this “is bad business, destroys shareholder wealth and ruins brands.” It’s a noble sentiment, but one that is fundamentally at odds with reality. As our editor-in-chief Nathan J. Robinson has written before, doing harm is often profitable, and the number of brands (personal or corporate) that have been irrevocably tarnished by their misdeeds is far smaller than those who have gotten off largely scot-free. Johnson & Johnson might have had to pay $4.7 billion in damages to women who developed ovarian cancer from using its baby powder, but that’s a tiny fraction of the company’s revenue ($81.5 billion in 2018 alone), and people are still buying Listerine, Neutrogena, and Band-Aids.

It’s clear that the idea of P.R. as a force for good is little more than wishful thinking. In the words of British journalist and author Heather Brooke: “Public Relations is at best promotion or manipulation, and at worst, evasion and outright deception. However, what it is never about is a free flow of information.” Today’s P.R. industry is exceptionally skilled at pretending otherwise. Whether its practitioners are working within an organization or as part of an outside agency, whether they’re representing individuals, businesses, or governments, the methods used are largely similar. None of these tricks are particularly complex at first glance, but that’s why they’re so effective—the best grifts are often the simplest ones.

We’ll now examine the three most important tricks in the P.R. professional’s repertoire. It’s worth noting that none of these tricks are intrinsically evil. In theory (and sometimes in practice) the same methods can be used to advance the goals of saving coral reefs or ensuring healthcare for all, just as easily as they can be used to advocate nuking Iran or using killer drones to patrol the U.S.-Mexico border. However, the rules of the P.R. game are much the same as those of college admissions: Those who start off with a big pile of money and know the right kinds of people have an all-but-insurmountable advantage.

Trick #1: “Media Placements”

The most valuable P.R. people in the world are those who can reliably secure their clients a platform in “A1” media outlets like the New York Times, Time magazine, and CNN. For customers who prefer to keep a lower profile, top P.R. pros can also seed favorable coverage of their preferred policies and positions in those same outlets while being careful to omit any mention of their involvement.

The firms who do this work are the crème de la crème of the P.R. profession, pulling in multi-million dollar retainers from ultra-wealthy clients. Take, for example, APCO Worldwide. One of the largest P.R. firms in the United States (it also claims to have 35 offices worldwide in cities from Paris to Tel Aviv to Shanghai), its website proudly proclaims: “We work for bold clients.” Many of those clients, like the Saudi Arabian royal family, are bold indeed—at least when it comes to beheading journalists, causing famines that kill millions of people, or torturing and murdering political opponents. APCO was not hired to spread the word about these accomplishments, of course. Instead, they were paid by the government of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to secure positive U.S. media coverage of his anti-corruption efforts against rival princes, government ministers, and minor officials. The campaign, which began in 2017 and concluded in early 2019, led to the detainment of hundreds of people in the Riyadh Ritz-Carlton, many of whom were tortured (with at least one person dying as a result of their injuries).

However, instead of acting as “the conscience” of the Crown Prince, as some P.R. ethicists might have hoped, APCO helped bin Salman land (among other media coups) a one-on-one interview with Norah O’Donnell on CBS’ 60 Minutes. In the March 2018 interview, O’Donnell touted the Crown Prince’s women-friendly reforms, praised him for “[curbing] the powers of the country’s so-called ‘religious police,’” and concluded by asking, “Does Saudi Arabia need nuclear weapons to counter Iran?”[1]

Shortly before that interview, APCO was the subject of an unflattering report from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism which exposed their role in the Crown Prince’s P.R. offensive. When asked why the firm’s briefings on the anti-corruption campaign just so happened to omit any mention of the rampant human rights abuses committed by bin Salman’s administration, an APCO spokesperson told the Bureau, “It is only now [March 2018] that such allegations are coming to light. Therefore, there were no concerns for us to raise with the client, and no reason for us to question the information we were given.”

This seems… dubious at best. In November 2017, Clay R. Fuller of the American Enterprise Institute (no great foe of the rich and powerful) explained that “‘anti-corruption’ sweeps’” like the Crown Prince’s “are a common authoritarian tactic for consolidating power” that “can cost people their freedom, health, money—and sometimes their lives.” If APCO was really that oblivious to what their client was doing (and why he was doing it) they wouldn’t be in business.

And if bin Salman hadn’t committed one of the worst P.R. blunders of all time just a few months after his 60 Minutes interview—the kidnapping, mutilation, and murder of the dissident journalist and Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018—it’s likely that the carefully-crafted image APCO helped bin Salman sell to the American public on CBS would be what stuck in people’s minds. Mass media is perhaps the most essential tool for mass manipulation, and P.R. firms like APCO are essential for getting the right message in front of the right people, no matter what that message might be.

Trick #2: “Network Building”

But how do P.R. firms like APCO build their pipelines into America’s top media outlets? It seems obvious that some kind of chicanery is at play, though few would be so unimaginative as to think it involves a team of jowly, besuited men marching into the newsroom with a handwritten list of talking points and a big sack of money labeled “BRIBES.”

Indeed, this is not the case—the people making the “request” tend to be extremely attractive and articulate, there’s not usually a paper trail (at least in the more sensitive cases), and the meeting place is most often a tropical paradise, a picturesque ski resort, or at least a feloniously expensive restaurant.

For honest journalists—insert your own snide, world-weary comment here—this can be an uncomfortable situation, as you might imagine. That’s why the P.R. people who approach them are often former journalists themselves. According to Muck Rack, a service that provides journalists’ contact information and areas of expertise to P.R. professionals, in 2018 there were almost six P.R. specialists for every journalist in the United States., up from a ratio of 4.6 to 1 in 2014. While there’s no data available on how many of these newly-minted P.R. pros come from the journalism world, the sheer number of articles with titles like “From Press Badges to Press Releases: Why Journalists Make the Move to PR” suggests the number is larger than you’d think—the writer of the aforementioned article, a P.R. pro herself, said that, “about 30 percent of our staff are ex-journalists or hold degrees in journalism.”

The reason so many journalists make the jump is simple: There are more jobs in P.R., and the money is better. In 2017, the average salary for a P.R. pro was almost $68,000, compared to $51,500 for journalists. And since P.R. is one of the few fields where a journalist’s skillset (e.g., “storytelling”) is easily transferable, this salary bump doesn’t require learning to code or acquiring other boring, tedious qualifications.

What it does require is 1) a shitload of emails and coffee dates and 2) attending events like the Wall Street Journal’s Tech Live, an extravagant event series held each year in Laguna Beach and Hong Kong. Tickets to the invite-only event run upwards of $5,000 apiece, though that’s a small price to pay for “premium networking opportunities.” Not only are many of the WSJ’s top journalists present, but also “executives, investors, and founders from around the world.” P.R. pros with especially good connections can get free tickets, plus speaking opportunities for their clients, either on the main stage or in more intimate settings like “fireside chats”—a euphemism for “a bunch of extremely drunk people sitting in comfy chairs listening to a mildly drunk person in an even comfier chair talk about the transformative power of blockchain for poor farmers in rural India.” Some of 2019’s most notable speakers include Ajit Pai, the chairman of the FCC; Ben Horowitz, the co-founder of venture capital giant Andreseen Horowitz; and Michael Brown, the director of the Defense Innovation Unit at the U.S. Department of Defense; and also supermodel Naomi Campbell, because fuck it, why not?

Aside from the swag bags (i.e., a potpourri of sometimes-expensive presents provided by the event’s corporate partners) and the ego boost for the client, attending events like these provide an opportunity for P.R. pros to increase their clients’ visibility in the eyes of both potential partners and journalists (whose future flattering profiles can be used to attract even more partners, by which we mean “people who can provide the client with money and/or access to power”). In lieu of having a brilliant invention or a world-changing vision for the future, a prestigious Contacts list is perhaps the most valuable asset a brand or government can possess. This allows their ideas and/or products to proliferate with the speed and vigor of a batch of E. coli.

Trick #3: “Optics”

The age of deepfakes (photos and videos that have been doctored so convincingly that they’re indistinguishable from real ones) may be fast approaching, but until that day comes, a picture’s still worth a thousand words—and video is worth even more, especially when it evokes moral outrage.

In the hands of the right P.R. firm, this can be an almost unimaginably powerful (and destructive) tool. During World War I, Bernays stirred up public hatred against the Germans by running thousands of short films in cinemas that claimed to expose the Huns’ (one-sided) barbarities. Decades later, similar techniques would be used by a P.R. firm called Hill+Knowlton to drag the United States into the Gulf War.

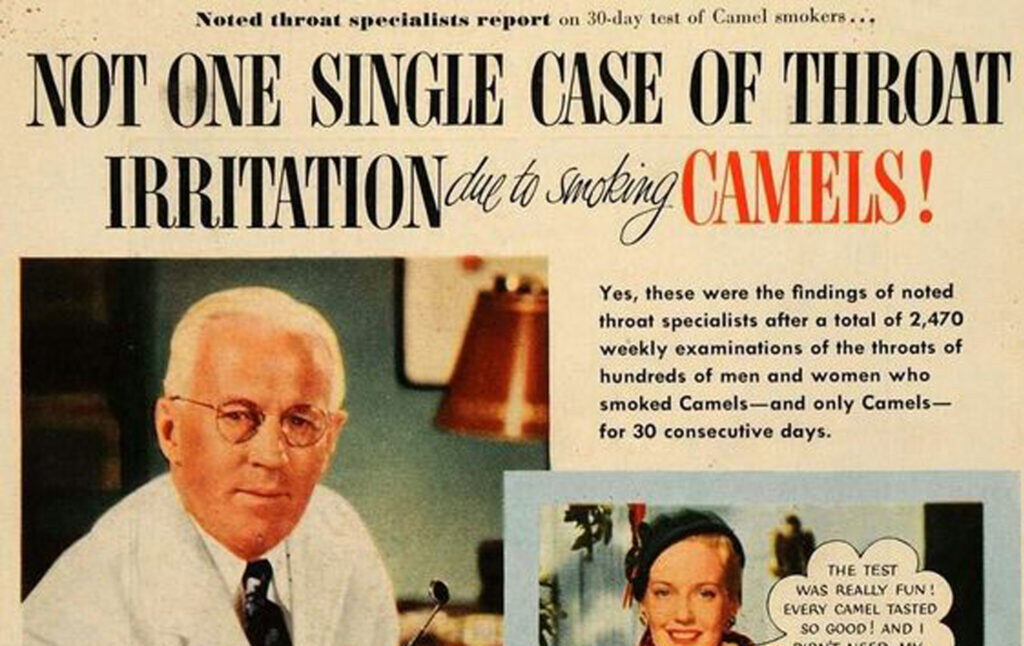

First, some background. Hill+Knowlton is one of the most blatantly malicious P.R. firms of the last century. In the 1930s, it helped steel manufacturers suppress worker dissent. In the 1950s, it helped tobacco companies cover up evidence their products caused cancer. In the 1970s, it co-founded the “Asbestos Information Association” to convince the public that asbestos had no health risks. Today, Hill+Knowlton helps the energy consortium America’s Natural Gas Alliance in their quest to pretend that fracking is environmentally friendly. Hill+Knowlton: the poster child for why the P.R. industry is reviled, and how damaging its work can be.

But the firm’s most infamous accomplishment came in 1990, shortly before the United States invaded Iraq for the first time. Known as “the Nariyah testimony,” the video can still be viewed in its entirety on YouTube. In it, a tearful 15-year Kuwaiti girl is shown testifying before the Congressional Human Rights Caucus about the horrific atrocities committed by Saddam Hussein’s soldiers during their invasion of her home country. “While I was [working as a volunteer nurse], I saw the Iraqi soldiers come into the hospital with guns,” she says in flawless English as she fights back sobs. “They took the babies out of the incubators. They took the incubators and left the children to die on the cold floor. It was horrifying. I could not help but think of my nephew.”

Her testimony was circulated by most of the country’s major media outlets, and President George H.W. Bush repeatedly referenced it as a justification for “humanitarian intervention” in Kuwait and Iraq. What was left unsaid was that the girl, who testified only under her first name Nariyah, was in fact the daughter of Saud al-Sabah, the Kuwaiti ambassador to the United States, and the events she described never happened. Nor was it mentioned that Hill+Knowlton—which had close ties to Human Rights Caucus chairmen Tom Lantos (D-CA) and Edward Porter (R-IL)—had helped organize the hearing in the first place.

By the time the truth was revealed, Iraq had already been bombed back to the “pre-industrial age,” as described in a United Nations report which estimated the Iraqi death toll to be between 142,500-206,000 people.

To be fair, the majority of P.R. photo and video “ops” are much more banal—a picture of a CEO shaking hands with workers, a short clip of a politician riding his tractor, and so on. Yet they serve much the same purpose: to give you, the humble citizen, visual proof that the client’s cause is a righteous one, and that they truly have society’s best interests at heart.

In some cases, this might even be true. As mentioned before, P.R. isn’t inherently evil, and mobilizing public sentiment isn’t always a bad thing (it’s the only way to combat climate change or police brutality, for example). All of the techniques described above can be used for noble purposes, and with the right amount of money and connections, they can be highly effective. But the realities of a capitalist system dictate that “noble P.R.” is the exception to the rule, since those who have the requisite money and connections to afford expensive P.R. usually acquired their wealth by nefarious means.

As citizens, there’s little we can do to stop the P.R. onslaught that now pervades every aspect of our lives. Sure, we can “question everything,” but most of us already do that, at least when a particular news story originates from a source outside our preferred bubble. Nor will it do much good to write a heartfelt letter to your congressperson or the CEO of your city’s most prominent P.R. firm—they have too much money to make from prolonging the problem to be interested in finding a solution. Direct collective action, like picketing outside the headquarters of a P.R. firm, might be effective in some cases, but it’s more effective for winning specific battles than the war at large.

The truth is that modern capitalism is inextricably entwined with the P.R. industry, depending on subtle misinformation to soften the many physical, financial, and spiritual blows that capital’s subjects must endure each day. Eradicating P.R. from a capitalist society is a fool’s errand. Until we achieve socialism, the best defenses against this bombardment of messages are 1) consuming as little corporate-owned media as possible, 2) remaining curious and thoughtful when we have strong feelings about distant events, and 3) learning about the great P.R. snafus of the past so we can begin to recognize the patterns.

And whenever we feel our heartstrings being tugged upon, we should ask ourselves:

“Who does this message serve, and why am I just seeing it now?”

[1]In fairness, O’Donnell also asked the Crown Prince, “What happened at the Ritz-Carlton? How did that work?” and “Do you acknowledge that [Yemen] has been a humanitarian catastrophe?”, though it would be exceedingly generous to suggest that she pressed him on either question.