Reflections on the Bernie Campaign

What it meant, why it inspired us, why we lost, and where we go now.

Bernie Sanders has suspended his campaign, and in the absence of some extraordinary event, it looks as if we will be stuck with Joe Biden as the Democratic nominee. The result should ultimately not be terribly surprising. Biden started the race as the favorite to win. He is a popular former Vice President. A Sanders victory would have upended “politics as usual” and been unprecedented. But Sanders felt, at a certain point, so close to victory that for those of us who had seen his victory as the best chance to begin building a better society, his withdrawal is crushing.

I remember after Bernie lost in 2016, and some of his delegates were crying at the convention, there were those who made fun of them. How can you cry over a political candidate? It must be a cult of personality. The critics never understood what Bernie Sanders has meant to his supporters. For us, his candidacy offered the hope that politics could be different, that problems like climate change, workplace exploitation, mass incarceration, healthcare costs, and student debt might actually be dealt with seriously rather than through pathetic incremental reforms. Finally, there was someone who seemed to grasp the reality of working people’s lives and give a shit about what happened to them. Bernie Sanders, for many of us, was the first presidential candidate who acted like he cared whether we lived or died. Barack Obama had sold us hope and then sold out to Wall Street. Kamala Harris mocked people who protest. Joe Biden told us directly that he had no empathy for us. Amy Klobuchar dismissed basic social democratic reforms as pie-in-the-sky rubbish. Elizabeth Warren often struck the right tone, but just as often she offered troubling defenses of the very system we objected to. But Bernie’s slogan “not me, us” captured what felt special about him: The purpose of the campaign was not to exalt Bernie, but to secure clear political victories like a $15 minimum, free college, and Medicare For All. When you asked a candidate like Pete Buttigieg why people should vote for him, he would cite his “alignment of attributes.” Bernie didn’t like talking about himself, but instead stayed relentlessly focused on ordinary people’s problems and how he would solve them. And he had a record to back it up. While people like Biden and Buttigieg seemed to discover progressive beliefs when those beliefs became electorally convenient for them, Bernie had spent decades as a lonely champion of the causes we cared about. While he could be exasperating or disappointing, we never doubted that he was principled and that he would fight to the death for us.

I could ramble for ages about what Bernie Sanders has meant to me, and to millions of others. How he made us feel less frightened and alone, how he raised our expectations and told people they had dignity and that they did not need to prove their moral worth in order to be entitled to the basics. The reason forklift drivers, bartenders, and teachers donated more to Bernie than any other candidate is that Bernie respected them. I am sure plenty of people will write their thank-you notes and tributes. Mine would go a dozen pages.

But since I have been saying the same thing for five years now, trying to convince people that Sanders is good and worth supporting, and since it’s not terribly useful to keep saying that now, right now it might be more helpful to write about some of the lessons we can learn from this whole thing and address that question of Where The Left Goes Now. Why did Sanders not succeed? What could be done differently next time?

As I say, in one way we should not have been surprised that Sanders did not win, because the U.S. has never had a democratic socialist win a major party primary. Only one of Sanders’ senate colleagues, fellow Vermonter Patrick Leahy, endorsed his candidacy. Fewer than 10 of the 232 Democrats in the House of Representatives endorsed him. Not a single current or former governor endorsed him. This is what it means to say that the “party establishment” was against Sanders: Almost nobody with a position of power and influence in the Democratic Party supported Sanders. If the “party decides” theory of presidential nominations is true, that unelected party leaders essentially pick the candidate before the ballots are cast, then it would have seemed near impossible for Bernie, a person detested by most party leaders, to win.

And the same was true in the press. Not a single one of the country’s major newspapers endorsed Sanders. In fact, many of the country’s “progressive” publications declined to come out for him; the Nation waited until last month, when the contest was effectively over, to endorse him, and In These Times treated Sanders and Elizabeth Warren as interchangeable. (Their nonprofit structure may prevent outright endorsements, but the nonprofit Jacobin adopted a very different tone.) Activist groups largely stayed out of the race so long as Warren was in. (Though there were groups, like the Sunrise Movement, that got behind him.) Justice Democrats did not endorse Sanders until last month. Same with Democracy for America. (Remember, he declared his candidacy in February 2019!) Few national labor unions, except the American Postal Workers Union and National Nurses United, endorsed Sanders (and Sanders even encountered opposition from the more “progressive” parts of the labor movement like UNITE-HERE). Despite Sanders’ emphasis on the need for a Green New Deal, environmental organizations like the Sierra Club did not endorse him. The list of prominent “journalists and commentators” who backed Sanders is thin, containing about 25 people including both myself and conservative talk show host Hugh Hewitt, who said he was actually a Trump supporter who didn’t really support Sanders but just wanted Democrats to be “honest” about their socialism.

Sanders had a lot of grassroots support, having raised vastly more money through small-dollar donations than any other Democratic candidate. But he had almost no institutional support: Labor unions, media organizations, public intellectuals, activist groups mostly declined to join Sanders. The progressive left fights an uphill battle at the best of times. But to fight without the support of unions and activists, or the influence of newspapers and public intellectuals, is damn near impossible.

To me, looking at the race in the rear view mirror, the lack of support from people Sanders needed is one of the most critical factors explaining Sanders’ loss. Some you would have expected to endorse him, like Sara Nelson of the flight attendants’ union or Medicare for All champion Ady Barkan, did not. Tulsi Gabbard, who endorsed Sanders in 2016, this time ran against him and probably siphoned votes from him, despite having no chance of winning.

The effect of public support, as with many other factors shaping the outcome of a race, is difficult to quantify. What does an endorsement do? Well, it means that everyone who respects and trusts a known activist or politician becomes marginally more likely to listen to the person that person has endorsed. It’s not much on its own, but when lots of people you respect are coming out for a candidate, you are likely to notice.

And we shouldn’t even talk about mere “endorsements.” People need to actually campaign for the candidates they believe in. Justice Democrats should not just have endorsed Bernie, they should have thrown resources into it. Instead, they waited until after he had already essentially lost in order to endorse him. This was useless.

The Warren Factor

Another giant looming factor in Bernie Sanders’ loss is the campaign of Elizabeth Warren. The damage that this did is hard to measure, but there is good reason to conclude it was severe. This magazine warned early on that it was very damaging to have two people competing for the “progressive” vote. Polling in January—in the lead-up to Iowa—showed that while Warren was doing relatively poorly, particularly among voters of color, her presence in the race was peeling away a large number of white, college-educated voters who would otherwise be expected to go to Sanders. The Washington Post noted that “the most pronounced second-choice shift in the Democratic primary field was Warren supporters going to Sanders,” and the Post documented in the lead-up to Super Tuesday that having Warren still in the race was significantly eating into Sanders’ support:

Not only is the second-choice path for her voters more explicitly pointed at Sanders than between Klobuchar and Biden or Buttigieg and Biden, but there are more of them who could migrate. Warren averages about 15 percent in national polls—about the combined total of Buttigieg and Klobuchar. So it’s a bigger block, and it would probably be a bigger windfall for Sanders.

Let’s just remember roughly how the voting went in order to understand what a disaster Warren’s continued candidacy was for Sanders. By the time of the Iowa caucus on February 3, Warren had slipped far behind Sanders in both polling and fundraising. As the Post wrote, Warren supporters were sympathetic to Sanders and considered him their second choice, but Warren stayed in the race even though it was clear she would come out well behind Sanders. Around that time, I was begging Warren supporters to switch and not vote for her in Iowa, saying that continuing to support her increased the chances not of her victory, which was increasingly unlikely, but of Joe Biden being the ultimate nominee.

The argument for switching to Sanders did not depend on whether one liked or disliked Warren’s politics. Even if Warren and Sanders had been identical, and Warren had been a staunch leftist, splitting the progressive left’s votes between two candidates makes it less likely a progressive will win.

Warren came in third in Iowa, significantly behind Sanders and Pete Buttigieg. Bernie received the most votes, but the delegate allocation math was messy enough that the state was spun in the media as either a tie or a win for Pete Buttigieg. If a fraction of Warren supporters had switched over, Bernie would have had a clean win, and gained momentum and positive media coverage. Then there was New Hampshire (February 11). Here, Warren came fourth, receiving only 9 percent of the vote. Bernie won with 25 percent, but Buttigieg was a close second.

Here, it should have been clear how much damage Warren was doing. She had lost again, this time very badly in a state next door to her home state. If she couldn’t do well in New England, she was toast. But what she was managing to do was keep supporters of her losing campaign from going to their second choice candidates. If she had not contested the state, and had dropped out to endorse her supposed fellow progressive candidate, Bernie would have won comfortably. Instead, it was a tight victory over Buttigieg.

Personally, I thought Warren should have dropped out before the voting started at all, since by that point (early February) her poll numbers were bad (particularly with voters of color), her fundraising was far behind Sanders, and every race in which there was more than one progressive candidate made it more likely Biden would win. But once Warren failed so badly next door to home, she really should have left the race. Bernie’s big win in Nevada (February 22) should have been the last straw.

But Warren stayed in. Joe Biden rebounded in South Carolina (February 29). And then, shortly before Super Tuesday (March 3), Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar quickly dropped out and endorsed Joe Biden. The centrists were consolidating (not fully—Bloomberg was still in). But, even though polls showed she was going to lose badly, Warren did not encourage progressives to do the same as the centrists were doing. She stayed in. And as expected, she lost, even coming third in her home state of Massachusetts. But the consolidation of the centrists helped produce a string of Biden victories in states Sanders had hoped to win. Biden won Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Texas.

In each of these states, the margin Biden won by was smaller than the number of votes Warren received. At the extreme end, in Maine, Biden beat Sanders by 1 percent while Warren received 15 percent, so that only a small percentage of Warren voters switching to the other progressive candidate would have changed the outcome. Super Tuesday effectively finished Bernie off. Massachusetts and Texas were essentially must-win states. After Super Tuesday, with Biden having won “Bernie states,” a narrative developed that Biden was “electable” and Democrats were breaking in his favor. Elizabeth Warren dropped out after Super Tuesday, but did not endorse or campaign for Sanders. The Michigan primary (March 10) was effectively the end of the Sanders campaign.

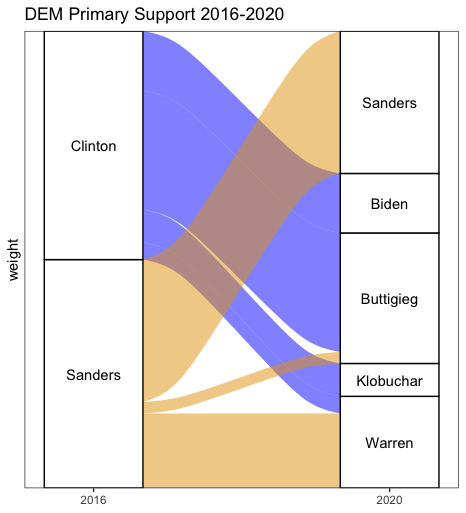

Now, I have seen a lot of people downplaying the effect of Warren’s campaign on Sanders’ ultimate loss. Generally they say something like: Well, all Warren supporters would not have gone to Sanders, actually they would have probably evenly split, it wouldn’t have made a difference. But as the Washington Post documented, in December and January, Warren supporters actually did tend to have a favorable opinion of Bernie and see him as their second choice. Anecdotally, the people I know who were pro-Bernie in 2016 tended to split into Sanders and Warren camps this time around, but there was no question of them supporting Biden. Washington Post data scientist Lenny Bronner showed how, in Iowa, the Sanders coalition in 2016 largely split in 2020 between Sanders and Warren:

But even if we don’t see it as conclusive that the pre-Super Tuesday polling showed Warren people had been favorable to Sanders before Biden picked up unstoppable momentum, we can’t merely look at what voters said they would do. We have to think about what they would have done if Warren had dropped out and campaigned for Sanders. The majority of Warren voters were saying Sanders was their second choice even without Warren herself having endorsed and pushed for Sanders. If she had done that, and made a case to her voters for why having a progressive nominee was important and why Joe Biden completely sucks (which he does), many more would likely have gone over to Sanders.

Elizabeth Warren did the opposite of this. Instead of understanding that if we were to have a progressive nominee, she needed to drop out and endorse Sanders, she began attacking Sanders. She said that Bernie had told her a woman couldn’t beat Donald Trump, launching a vicious debate over whether or not Bernie was a sexist. (What rankled with many Sanders supporters is that because Warren did not say clearly what Sanders had actually said and in what context, it was difficult to know whether this was simply a conflict of interpretations or Sanders had said something genuinely sexist. Sanders had encouraged Warren herself to run in 2016 instead of him, so it was difficult to believe he was against having a woman run against Trump. But Warren did not say whether the remark was open to a more charitable interpretation, or give an opportunity to discuss and resolve the difference, and when Sanders denied having thought a woman couldn’t beat Trump, Warren refused to shake his hand.)

Then Warren said Bernie Sanders got nothing done as a legislator (a total falsehood), declining to defend him when Hillary Clinton said nobody liked him. She attacked his supporters as toxic. She implied she would fight all the way to the convention. It got so bad that the executive director of Justice Democrats, which had remained neutral, “called on Warren to stop ‘attacking’ Sanders and pledge to ‘give her delegates to him if he has more votes to ensure a progressive wins the nomination.’”

None of this helped Warren’s chances of winning. She did worse and worse. But as BuzzFeed reported at the beginning of March, what it did do was keep progressives divided, and ensured that progressive organizations that had stayed on the sidelines did not rally behind Sanders:

As centrist Democrats consolidate around Joe Biden’s presidential campaign, progressive organizations that have divided in support between Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren said they do not have a plan to quickly band behind one of the two to form a coalition against the moderate threat… groups that have backed Warren for months or years — like the Working Families Party and the Progressive Change Campaign Committee — are showing no sign of relenting in their support or beginning to coalesce around Sanders’ frontrunning campaign to match the support Biden’s now receiving.

The Working Families Party did ultimately switch from Warren to Sanders—but by the time they did, it was far, far too late. Centrists had seized their moment and pushed Biden over the top.

If Warren’s supporters ultimately did break fairly evenly for Sanders and Biden, a lot of that may be because Warren herself worked to sour her supporters on Sanders. When she dropped out, she declined to endorse him, instead choosing to perform in skits on SNL and once again publicly lambast his supporters for having sent her mean emojis on Twitter. She did not give her voters even the slightest hint that Sanders was preferable to Biden, thus implying that it didn’t matter which one won.

Warren was not by any means “required” to endorse Bernie’s candidacy. It wasn’t out of some personal obligation to him that she should have endorsed him, but out of a moral necessity that comes from believing in progressive politics. If you have a set of values, if you care about what happens in the world and you are in a position to advance those values by uttering a single sentence, I don’t see how it’s excusable not to act. And, days before Super Tuesday, threatening to continue fighting Bernie Sanders for delegates all the way to the convention? What on earth could justify this?

By the time Warren finally dropped out, it was probably too late for her word to have affected much, but choosing not to endorse Sanders is still unforgivable. Warren knows Biden’s politics. Her first foray into national politics was opposing the terrible bankruptcy bill he wrote (and now lies about having written). She knows that he will not actually stick up for the causes she says she believes in. She knows how urgent the climate crisis is. And yet she did not lift a finger to help the one remaining candidate that our moment urgently demands. I find this to be a complete betrayal. I started off the primary liking Elizabeth Warren a fair bit, but by the time it ended, I no longer saw her as any kind of ally of progressive politics. I do not see any principled explanation for the non-endorsement, other than “Elizabeth Warren is not actually as progressive as she pretends to be.” (Which was becoming clear as early as November.)

Lessons To Learn

What lessons are we to learn from that? Well, as Patrick Stewart once said while playing Vladimir Lenin, “never trust the liberals. They will betray you.” Personally, I developed a bit of a reputation for being harsh on Elizabeth Warren over the course of the primary, but when I look back on it, my main regret is that I wasn’t more critical earlier, because it should have been obvious that with the entire Democratic party establishment looking to line up behind a candidate to stop Sanders, we could not afford to lose any progressive votes.

The main practical lesson here has to be: Never again can we split the vote this way. Never again can unions or organizations like Justice Democrats be on the fence. The “progressive primary” needs to be run before having a second losing candidate in the race appealing for progressive votes could act as a “spoiler.” We’ve got to figure out a way to avoid a calamity like that happening again. Our side is very unlikely to win generally, and having our energies divided between two candidates just makes it so, so much more difficult.

Now, there were internal mistakes made within the campaign, too, often serious ones. A few I’d personally list:

- Bernie Sanders inexplicably does not seem to prepare for debates and thus missed crucial opportunities to create memorable media moments that would have resonated.

- As David Sirota explains, Bernie declined advice to draw sharper contrasts with Joe Biden. Personally I think it was nuts not to point out that Joe Biden lied and pretended to have been a civil rights activist while Bernie actually was a civil rights activist. That’s such an egregious and offensive falsehood on Biden’s part that it seems weird to just give it a pass.

- Assuming South Carolina wouldn’t matter, the campaign made little effort to win it. If Bernie had lost less badly it would have done less to revive Biden’s campaign.

- The campaign failed to craft a good strategy for reaching elderly voters and African Americans. Bernie did great with Latinos this time around but still didn’t break in with these other groups.

- While the campaign produced at least one brilliant ad, and had an excellent podcast (hosted by Current Affairs’ own Briahna Joy Gray)—probably the first podcast ever by a political candidate to be Actually Good—on the whole the quantity of good advertising was lower than in 2016. The team that did the “America” ad did not return this time around. They were missed. The best videos promoting the campaign actually came from independent producers rather than the campaign itself.

- Too many policies. Jeremy Corbyn made this mistake. Instead of sticking to a few simple talking points Sanders was a little unfocused compared to 2016.

- Failure to seize the coronavirus moment to try to revive his campaign. By the final debate with Biden, Bernie was resigned to losing. I thought it was a bad idea to give up, particularly as the crisis has laid bare just why we need Medicare for All and workplace protections.

I could go on, and I am sure leftists will be scrutinizing what happened in more detail for a long time. One theory I do not buy is that Sanders’ mistake was relying on a “Marx-inflected” theory of politics. Zack Beauchamp writes in Vox that:

A basic premise of Marxist political strategy is that people should behave according to their material self-interest as assessed by Marxists — which is to say, their class interests. Proposing policies like Medicare-for-all, which would plausibly alleviate the suffering of the working class, should be effective at galvanizing working-class voters to turn out for left parties.

Beauchamp says that this theory is wrong. But he does not show that Sanders or his supporters actually believe anything of the kind. I don’t know anyone who thinks that merely proposing socialist policies wins elections; if it did, Eugene Debs would have been elected president in a landslide. There are very serious obstacles to showing disaffected people why they should be excited by something like single-payer healthcare. (One of those obstacles is that Democratic politicians like Pete Buttigieg and Joe Biden are constantly lying to the public and implying that Medicare For All would leave people uninsured or with less money, or, like Warren, they claimed that Bernie didn’t have a plan to pay for Medicare for All, which was also a lie.)

One of Beauchamp’s mistakes is treating the left’s theory of the general election as a theory of the primary. He actually quotes me:

It’s hard to overstate how central the theory of Sanders’s popularity with middle- and lower-income whites was to his campaign and its outside supporters. They saw his unique touch with his voters as not just a strategy for winning the campaign, but a key reason why socialism as a political project was viable in today’s America. “As in 2016, Bernie is different from other Democrats in that he knows how to speak to Trump’s own voters. Not only does he beat Trump consistently in head-to-head polling, but he offers ordinary people an ambitious social democratic agenda that is designed to deal with their real-world problems,” Nathan J. Robinson wrote in March in the leftist magazine Current Affairs. “When Bernie tells working people he is in their corner, they can believe him.” The failure of this approach meant that Sanders needed to rely heavily on the second prong of his 2016 coalition, young voters, turning out in large numbers.

I am sure you will have noticed the mistake. I wrote about Sanders’ ability to speak to Trump voters. That approach would have “failed” if Sanders had lost the general election. In fact, the whole theory the left had was not that the primary was easy to win, but that we would win the general election, because we would be given an opportunity to court independents and the politically disaffected—the kind of people who do not vote in party primaries. This is what we’ve been saying consistently. We know that it’s hard for a socialist to win the Democratic primary; the open question is whether a leftist Democratic nominee would prove an effective antidote to Trump. Tragically, we will not find out what could have happened, because centrists banded together to squash us and make sure the 2016 playbook was run all over again—except this time with a candidate who sometimes struggles to finish a sentence.

Joe Biden still might actually win, now that coronavirus has thrown such a chaos factor into the race. If, by November, we’re in a depression and many people have died unnecessarily, voters might be ready to vote for an inanimate object over Donald Trump, and Biden fits the bill. (Some writers are openly suggesting that Biden’s main qualification for office is “has a pulse and is not Trump.”) Personally I hope Trump loses, even though it is very hard for me to defend Biden, given that a woman has told me directly that he sexually assaulted her and I have spoken to two corroborating witnesses. Several more years of Trump, though, might well spell the end of democracy as we know it. Faced with this dreadful choice, I am holding out for some miracle that will make sure Biden isn’t the nominee. I do not know what that could conceivably be, though.

As we get closer to November, we can discuss what we ought to do about voting, whether “lesser evilism” is the way to go. (I have said, and still believe, that spoiler votes in swing states are bad.) But voting in general elections is a five-minute job. The real question is: What do we do now? Well, the good news is that despite people portraying Sanders’ loss as evidence of the left’s failure, it does still actually show that we are ascendant compared to where we used to be. In 2016, Bernie Sanders was the underdog throughout the primary. This time, at one point he was on track to win the nomination outright, and people were surprised when he didn’t! I would say that’s progress.

It’s clear that the left is institutionally weak, though. If we take over unions, media outlets, and legislative positions, we will be in a much better position next time. In some ways, trying for the presidency before we could win more than a few congressional seats was incredibly ambitious. But it’s good that Bernie did it, because it inspired people and cultivated a whole new generation of engaged left activists.

Many people have come to me despondent asking for advice. I’ve felt despondent myself, especially looking at the prospect of four more years of Trump versus a loathsome corporate Democrat like Biden. But we shouldn’t actually despair, because we are slowly beginning to succeed. Take one small example: A $15 minimum wage was considered an absurdly ambitious goal when the Fight For 15 began. Incrementalist Democrats had always believed in nudging the minimum wage up a bit, not more than doubling it. But now, millions of workers are covered by a $15 minimum wage, and the idea has become so mainstream that the House of Representatives passed a $15 minimum wage bill last year. It’s becoming clear that if anything the target wasn’t ambitious enough!

In Austin, progressives fought and won paid sick leave. Kickstarter has unionized. Amazon workers are fighting back against the richest man in the world’s reckless disregard for their lives. People are raising their expectations and demanding what they deserve. This is, to quote the title of Meagan Day and Micah Uetricht’s essential new book on the future of the left, Bigger Than Bernie. We’re just getting started. (Anyone looking for hope or wondering what we do now to build power needs to pick up that book right away. It’s the best existing guide to where we go from here.)

So, look: An incredible campaign was run. It out-fundraised and out-organized everyone else. It was inspiring. Yes, it’s tough to see such a promising opportunity completely snuffed out, and to know what lies in store at the presidential level. And with coronavirus, the amount of new suffering and misery in the world is of a scale that is incredibly painful to even begin to think about. But the fight for justice is not optional and we are clearly building power steadily.

Instead of ending with further critique of anyone’s mistakes, though, let’s just take a moment to appreciate how much hard work was done, is still being done, by selfless individuals who have dared to “fight for someone they don’t know.” Everyone who contributed to this campaign in any way deserves great respect, because they are on the right side of history. And I still know that together we will win.