In my last entry on the virus, I mentioned how unexpectedly difficult it had been to write about the present crisis. even though there are so many things happening at once. After a certain amount of time all the stories of death and tragedy seem to bleed together, and it seems less like a series of events and just like one big event that moves slowly and about which there seems little useful to say. But while I say I was surprised, I shouldn’t have been, because I had just recently reread Albert Camus’ The Plague (1947), and it touches on exactly this. Camus writes:

“The narrator is well aware of how regrettable is his inability to record at this point something of a really spectacular order; some heroic feet, or memorable deed like those that thrill us in the chronicles of the past. The truth is that nothing is less sensational than pestilence and by reason of their very duration. Great misfortunes are monotonous. In the memories of those who lived through them, the grim days of plague do not stand out like vivid flames, ravenous and inextinguishable, beaconing a troubled sky, but rather like the slow, deliberate progress of some monstrous thing crushing out all upon its path.”

Or how about this, describing the feelings of those who wrote letters to family members living outside the city—letters they could not send, because the entire municipality was under quarantine:

“For weeks on end we were reduced to starting the same letter over and over again, recopying the same scraps of news and the same personal appeals, with the result that after a certain time the living words, into which we had as it were transfused our hearts’ blood, were drained of any meaning. Thereafter we went on copying them mechanically, trying, though the dead phrases, to convey some notion of our ordeal.”

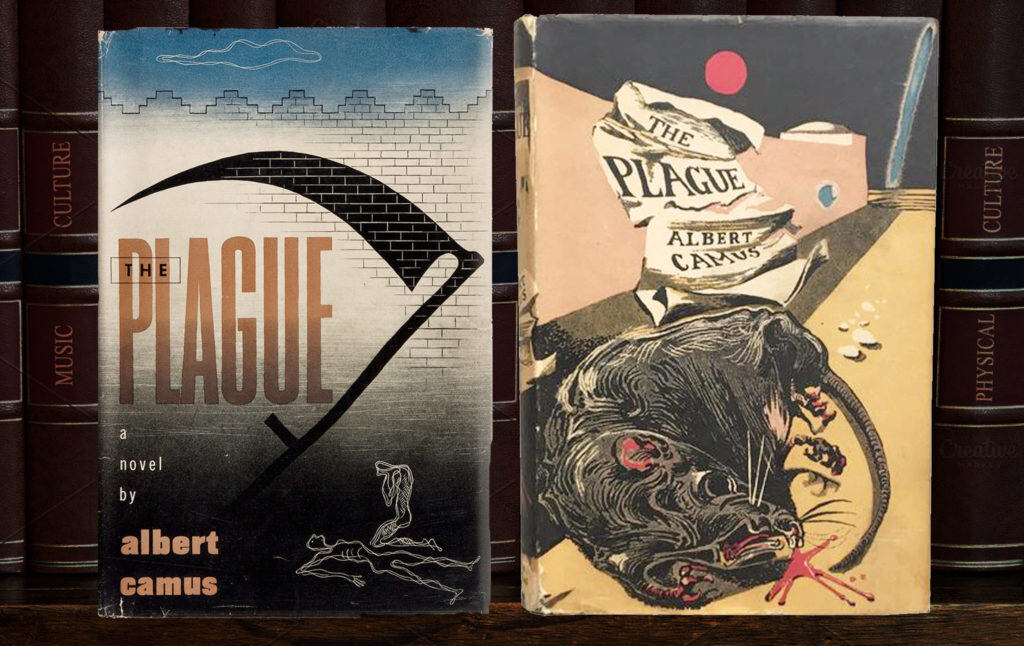

The Plague’s account of Oran being stricken by a horrific pestilence, and people struggling to stay alive and sane, might seem bleak reading during the coronavirus crisis, and part of me wanted to start the full Chronicles of Narnia for the first time instead. But The Plague is actually a somewhat comforting read because in parts, Camus articulates precisely, even eerily, what we ourselves are now going through, and also because the novel is a reminder that however bad these things get, they do, in fact, end.

But Camus understands the psychology of the plague-suffering society, and at one point notes that thinking about the “end” of a disease crisis while it is happening can actually be demoralizing. The residents of his fictional plague-stricken Oran “very quickly desisted” from “trying to figure out the probably duration of their exile” because:

“…when the most pessimistic had fixed it at, say six months, when they had drunk in advance the dregs of bitterness of those six black months, and painfully screwed up their courage to the sticking-place, straining all their remaining energy to endure valiantly the long ordeal of all those weeks and days—when they had done this, some friend they met, an article in a newspaper, a vague suspicion or a flash of foresight would suggest that, after all, there was no reason why the epidemic shouldn’t last more than six months; why not a year, or even more? At such moments the collapse of their courage, will-power and endurance was so abrupt that they felt they could never drag themselves out of the pit of despond into which they had fallen. Therefore they forced themselves never to think about the problematic day of escape, to cease looking to the future, and always to keep, so to speak, their eyes fixed on the ground at their feet.”

Makes sense. I’ve undergone the same adaptation myself, and you might have too. An excellent New York Times report on what lies in store for us in this crisis suggests, based on interviews with dozens of experts, that it may be years before we return to what was known as “normal.” (Though it wasn’t normal, and I hope we never return to it but instead find our way to something different and better.) Do you remember when Donald Trump was talking about “opening up the country for Easter Sunday?” He said the church pews would be filled. (Some were, and we will probably soon be seeing reports of parishioners with coronavirus—just as we are now seeing Wisconsinites with Covid-19 from voting in the April 7th primary that Republicans and Joe Biden said was safe.) There may be many false end dates touted and then passed, so it is best to keep our “eyes fixed on the ground at our feet.”

Many passages in The Plague resonate at the moment, and as I read it I noted down a bunch that felt insightful. Here, for instance, Camus mentions that every society seems incredulous that it could be victimized by a pandemic, even though we know pandemics have regularly occurred for all of human history:

Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world; yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky. There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.

In another passage, Camus mentions that the quirks of day-to-day life in the city seemed somehow to make the idea of being struck by a pestilence implausible:

He realized how absurd it was, but he simply couldn’t believe that a pestilence on the great scale could befall a town where people like Grand were to be found, obscure functionaries cultivating harmless eccentricities. To be precise, he couldn’t picture such eccentricities existing in a plague-stricken community, and he concluded that the chances were all against the plague’s making any headway amongst our fellow-citizens.

It sounds strange to say that eccentricities make plagues implausible, but I think I understand. Many times since coming to Florida a month ago, I have looked at a lizard sitting on the porch and gone “how can this peaceful lizard coexist with a national crisis?” My parents’ house here is a little oasis of tropical plants and since I have holed up here, the disease has been so invisible in my day-to-day life that it can be difficult to truly accept its reality.

But that’s more about the contrast between tranquility and tragedy. “Eccentricity” is different, but Camus is right that there is something jarring about knowing that people with such individuality, with such highly specific and unthreatening lives, can suddenly all face a threat like this. It is deeply weird. It is wrong. I think that does contribute to some of the conservative coronavirus denialism (which, incredibly, continues even now that coronavirus kills more Americans each day than any other cause and rapidly becomes by far the leading cause of death everywhere it manages to take hold). It is hard to believe that this could happen to us, though perhaps for conservatives that has more to do with feeling as if America is invincible and could never be felled by something so pathetically small and unmanly as a microscopic pathogen. (My colleague Aisling McCrea has a plausible theory that current and former imperial powers screw up their coronavirus responses in part because they have never had to take existential threats seriously enough.) Another factor in play is that we feel very “advanced,” and do not really see how small the medical progress we have made since the Victorian era is. The body’s miraculous immune system is still doing almost all the work in combating coronavirus, and the main contribution added by “civilization” is “staying away from each other,” which while important does not exactly represent a stunning scientific breakthrough. And of course, there is the fact that this whole thing just seems too dumb to be true in a certain way:

When a war breaks out, people say: “It’s too stupid; it can’t last long.” But though the war may well be “too stupid,” that doesn’t prevent its lasting. Stupidity has a knack of getting its way; as we should see if we were not always so much wrapped up in ourselves.” (Camus is right here about the absurdity of watching years-long projects collapse, and tens of thousands of perfectly good lives reach their end, thanks to an invisible wandering threat. But the quote also makes me think of the Trump presidency, and the inability of many Democrats to reconcile themselves to the fact that something so stupid as a “Donald Trump presidency” can be a thing that is really happening. It seemed too ridiculous to be possible before it happened, so they were complacent, but if they had read their Camus they would never have been taken aback by the sudden triumph of the Absurd.)

Another cause of “denialism” that Camus touches on is the remoteness and meaninglessness of deaths that exist to most people as mere statistics:

[T]he bare statement that three hundred and two deaths had taken place in the third week of plague failed to strike their imagination. For one thing, all the three hundred and two deaths might not have been due to plague. Also, no one in the town had any idea of the average weekly death-rate in ordinary times. The population of the town was about two hundred thousand. There was no knowing if the present death-rate were really so abnormal… The public lacked, in short, standards of comparison. It was only as time passed and the steady rise in the death rate could not be ignored, that public opinion became alive to the truth. For in the fifth week there were three hundred and twenty-one deaths, and three hundred and forty-five in the sixth. These figures, anyhow, spoke for themselves. Yet they were still not sensational enough to prevent our townsfolk, perturbed though they were, from persisting in the idea that what was happening was a sort of accident, disagreeable enough, but certainly of a temporary order.

In fact, that’s exactly what you’ll see from many right-wing commentators. Dinesh D’Souza, for instance, tweets:

Compared to what? Are they telling us how many people die nationwide—or worldwide—because of obesity? Stroke? Car accidents? Other contagious diseases? These #Coronavirus numbers must be viewed in some perspective. That’s what’s missing in so much of the frenetic media coverage.

And that can be persuasive to people, because as Camus writes, most of us are not experts and don’t really know what to make of changes in reported numbers. Unless people we love are dying before our eyes, it may seem crazy that we’ve shut the economy and thrown tens of millions of people out of work in order to contain the virus. A threat, even a very severe one, is only real to us when fulfilled, whereas unemployment is real in the here and now. Unfortunately, this has now led to some of the most ill-conceived protests in the history of mass action, as right-wingers gather to call Covid-19 a communist plot. The protests are possibly astroturfed, but certainly egged on by Trump, who has been following the schizoid but politically brilliant strategy of demanding governors “liberate” their states and then immediately switching back to siding with public health officials. I am not too worried about the protests, though, because if they succeed it will only be a temporary victory. Sooner or later we shall hear reports of participants dying of coronavirus (as we have with pastors who have insisted on assembling their flocks), and I suspect they will peter out once the participants all start coming down with coronavirus. Not much can silence the ignorant in this country, but death does tend to quiet a person down a bit.

* * *

Camus’ words also sound prophetic when he describes the process of adaptation to an ongoing pandemic. Here, he talks of the way that, at first, we try to live in an imagined normalcy, pretending that nothing has changed before inevitably having to confront the fact that things are no longer as they were:

Thus the first thing that plague brought to our town was exile… that sensation of a void which never left us, that irrational longing to hark back to the past or else to speed up the march of time, and those keen shafts of memory that stung like fire. Sometimes we toyed with our imaginations, composing ourselves to wait for a ring at the bell announcing somebody’s return, or for the sound of a familiar footstep on the stairs; but, though we might deliberately stay at home at the hour when a traveler coming by the evening train would have arrived, and though we might contrive to forget for the moment that no trains were running, that game of make-believe, for obvious reasons, could not last. Always a moment came when we had to face the fact that no trains were coming in. And then we realized that the separation was destined to continue, we had no choice but to come to terms with the days ahead. In short, we returned to our prison-house, we had nothing left us but the past, and even if some were tempted to live in the future, they had speedily to abandon the idea—anyhow, as soon as could be—once they felt the wounds that the imagination inflicts on those who yield themselves to it.

Camus set himself something of a challenge by writing The Plague, because he had to create a novel out of a kind of tedium that stretched over months, months that for his characters would seem never-ending and monotonous. We can see in the earlier passage about the lack of events and heroics that Camus wanted to describe things as they would actually be in a plague, not as they would be in a work of fiction that merely used a plague as a framing device. He describes, for instance, the phases of adaptation. At first, the people of the town, “alarmed, but far from desperate… hadn’t yet reached the phase when plague would seem to them the very tissue of their existence, when they forgo the lives which until now it had been given them to lead.”

Thus each of us had to be content to live only for the day, alone under the vast indifference of the sky. This sense of being abandoned, which might in time have given characters a finer temper, began, however, by sapping them to the point of futility. For instance, some of our fellow-citizens became subject to a curious kind of servitude, which put them at the mercy of the sun and the rain. Looking at them, you had an impression that for the first time in their lives they are becoming, as some would say, weather-conscious. A burst of sunshine was enough to make them seem delighted with the world, while rainy days gave a dark cast to their faces and their mood.

I feel that. Acutely weather-conscious I indeed have become. And the vast indifference of the sky really makes itself obvious these days. I am not yet sapped to the point of futility, but we’ll see how long this thing goes on. At the moment, there is still hope of “opening up” quite soon, though this seems to require a belief that magic is real. The mayor of Las Vegas, asked why she thought Covid-19 would not breed in Vegas restaurants and casinos based on what we know from China, replied: “this isn’t China. This is Las Vegas, Nevada.” If we believe that the virus will be so intoxicated with Vegas attractions and the Sin City lifestyle that it will simply forget to kill anyone there, this theory may hold up. But if we do not believe this, it is murderous madness. The mayor even went so far as to offer up her city as a “control group” for letting infections run rampant, though I am not sure what part of a mayor’s lawful authority includes the power to present her citizens as a collective human sacrifice.

The more honest conservatives admit that they simply don’t care if people die as long as their rich friends remain rich. “There are more important things than living,” said the Texas Lt. Governor. (We should note as a scientific fact that the fuckers who say things like this always seem to live forever.) It has been observed that (largely white) Republicans have escalated their calls to reopen the economy soon after it has become clear that Covid-19 hits Black communities and vulnerable people the most, and I do think there are Nazi-ish undertones to some of the anti-lockdown protests, which seem to operate on the premise that it doesn’t matter how many members of the underclass die to save the privileges of the rich.

In case you have not read The Plague, I will not tell you much about the plot or the characters. I will understand if you don’t want to read about a plague right now, and perhaps are opting for lighter and more escapist fare. But if you do pick it up, you’ll find that it’s not just a good description of life during a pandemic. It is also about human goodness and its sources, how evil things happen and how people react to them, and what it means to care for one another. The descriptions of mass graves depressed me, but the book itself did not; I felt far more alive and hopeful at the end of The Plague than I do by the end of my morning newspaper. It conveys, far more than I than anything I see in the newspaper, the message of that lovely Vonnegut quote I return to as often as I can: “We’re here to help each other through this thing, whatever it is.”

As of 4/25/20

Total confirmed cases in the U.S.: 953,000

Total deaths in the U.S.: 52,264

New deaths in the last 24 hours: 1,959