Animals Are Pointless, And We Should Be Too

The value of life does not depend on “productivity.”

What do ducks do all day? I have been watching some recently, and the answer is: not much. They float around. They eat. They quack. They poop. They waddle from pond to tree and back again. Sometimes they reproduce using their weird corkscrew genitalia. But they do very little work. Other animals are much the same. I watched some turtles the other day, sitting beside a lake. They basked in the sunshine. Then they went in the water for a bit. Then they came out again. This seemed to be their entire life.

I am not saying animals do no labor. Oftentimes, the struggle to survive is intense, and many are constantly exerting themselves. But once they’re fed and rested, a lot of what they do consists of standing around. Or sitting. Or wandering this way and that. Cats, as we know, mostly just sleep, and when you think about it, it’s rather incredible that millions of years of evolution have produced a creature whose main purpose is just to lie in one spot unconscious.

Animals do not seek meaning, as far as we can tell. The very concept of a meaningful life is incomprehensible to them. There is just life, and life consists of the things that need to be done and then things they just seem to like doing. But one animal is quite different: us. The human. Many humans have a very strange idea that life should consist of more than just quacking and floating. It should be “meaningful,” whatever that is.

Consider the troublesome case of Ezekiel J. Emanuel, brother to Rahm and health policy adviser to Joe Biden. Emanuel once wrote an essay called “Why I Hope To Die At 75.” In it, he argued that after 75, life becomes less and less worth living. He documents all the ways in which life as an elderly person can be unpleasant due to physical and mental decline. He is dismissive toward efforts at life extension (which I favor). He decides that given how much being old tends to suck, 75 should be “enough” years for anyone.

The conclusion of the essay makes very little sense to me. I do not know why anyone would choose the number 75 solely because it is a population-level average of when life begins to get worse, instead of saying that each person should want to live as long as their own personal quality of life is good. (Actually, I know exactly why. Because saying “you should want to live as long as your life is good” is banal and won’t get you into the Atlantic whereas irrational contrarianism will.) But what interests me most about Emanuel’s take is that a central part of his case against life after 75 is that old people are not as “creative” or “productive.” Listen to him:

It is not just mental slowing. We literally lose our creativity. About a decade ago, I began working with a prominent health economist who was about to turn 80. Our collaboration was incredibly productive. We published numerous papers that influenced the evolving debates around health-care reform. My colleague is brilliant and continues to be a major contributor, and he celebrated his 90th birthday this year. But he is an outlier—a very rare individual… American immortals operate on the assumption that they will be precisely such outliers. But the fact is that by 75, creativity, originality, and productivity are pretty much gone for the vast, vast majority of us… we choose ever more restricted activities and projects, to ensure we can fulfill them. Indeed, this constriction happens almost imperceptibly. Over time, and without our conscious choice, we transform our lives. We don’t notice that we are aspiring to and doing less and less. And so we remain content, but the canvas is now tiny. The American immortal, once a vital figure in his or her profession and community, is happy to cultivate avocational interests, to take up bird watching, bicycle riding, pottery, and the like. And then, as walking becomes harder and the pain of arthritis limits the fingers’ mobility, life comes to center around sitting in the den reading or listening to books on tape and doing crossword puzzles. And then … Living too long is also a loss. It renders many of us, if not disabled, then faltering and declining, a state that may not be worse than death but is nonetheless deprived. It robs us of our creativity and ability to contribute to work, society, the world. It transforms how people experience us, relate to us, and, most important, remember us. We are no longer remembered as vibrant and engaged but as feeble, ineffectual, even pathetic.

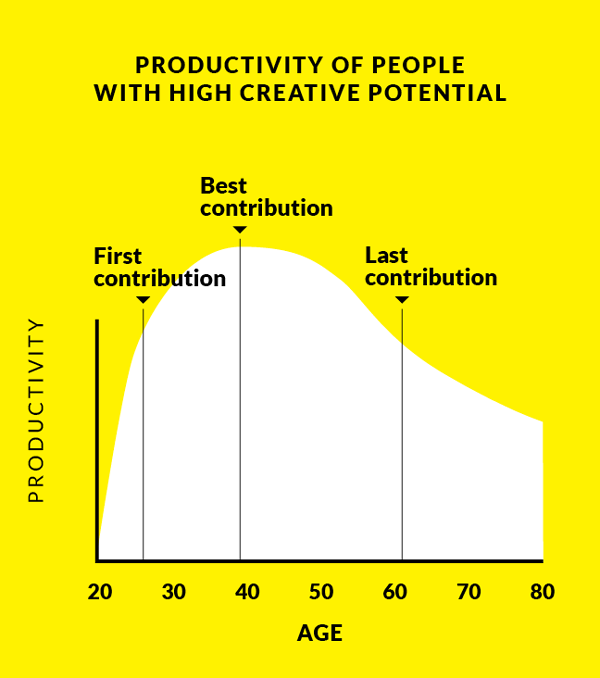

Emanuel also included the following chart to illustrate that creative people’s “contributions” decline over time:

Emanuel expanded on the point in an interview he gave some years later, in which he questioned of old people “whether our consumption is worth our contribution.” In it, he was asked what his problem was with old people just enjoying their lives.

Q: What’s wrong with simply enjoying an extended life?

A: These people who live a vigorous life to 70, 80, 90 years of age—when I look at what those people “do,” almost all of it is what I classify as play. It’s not meaningful work. They’re riding motorcycles; they’re hiking. Which can all have value—don’t get me wrong. But if it’s the main thing in your life? Ummm, that’s not probably a meaningful life.

Now, personally I would not describe a 90-year-old who hiked and rode motorcycles as not living a “meaningful” life. It sounds like a fucking awesome life. But I also think Emanuel seems to have a disturbing case of the illness known as “neoliberal brain worms,” one symptom of which is viewing a person’s human worth as synonymous with their “productivity” (or even, in extreme cases, the market value of their contributions).

Emanuel is arguing, and I do not think I am misstating him, that life becomes less worth living to the extent one engages in “play” rather than “meaningful work,” and to the extent one’s “contributions” are outpaced by one’s “consumption.” He seems to have a little equation in his head where as soon as your consumption exceeds your production you become a “net minus” on society and you are therefore fit for death. He is not saying anyone should murder you, or that you should kill yourself, but merely that you are a burden whose continued existence is not valuable.

In this, I see a lot of the values that I most detest. Measuring people by their “contributions” seems perverse to me, because it implies a kind of Social Darwinism where being weak (Emanuel mentions being “feeble, ineffectual, even pathetic”) is looked upon as making your life less valuable. This is the way fascists think. By contrast, the way egalitarians and socialists think about humanity is that every life is equal. We cannot imagine making a graph of people’s “relative contributions over time” and suggesting that a 75 year old who simply wants to potter about the garden is not living meaningfully. (Emanuel speaks disdainfully of the way life “comes to center around sitting in the den reading.” My life already centers around this so I am somewhat offended to hear him classify it as a form of decline.)

I am not surprised that this guy is Joe Biden’s healthcare policy adviser. (Though it’s a little ironic that a guy who thinks people are generally feeble and useless after 75 supports a 78-year-old presidential candidate.) His article shows many of the flaws that characterize contemporary Democratic thinking. For instance, he speaks of the way that the elderly can become a burden on younger relatives who must take care of them or support them financially. To an egalitarian, this leads to the conclusion “we need to have good public elder care to minimize these hardships.” To a neoliberal utilitarian, it leads instead to the conclusion “perhaps the maximization of aggregate happiness units is best facilitated through selective reduction of populations whose burdensomeness exceeds their happiness-production capacity.”

We socialists do not measure people’s value quantitatively like this, for the same reason that we do not measure a duck’s worth quantitatively. (This inability to place a market value on wildlife, as I have written before, has unfortunately meant that under capitalism they are treated as completely disposable and massacred by the billions.) If it costs those of us who can work so that those who are old can “play” without having to produce, so the fuck what? The moral obligation that we all have is to help sustain the life around us, and we hope that others will sustain us too when we are “feeble” and in need.

I do think Emanuel’s ideology is in many ways a very American way of looking at existence. In the United States, work is the point of life, rather than life being the point of work. In many European countries, leisure is taken very seriously indeed, and the purpose of working is so that we may have more of it. It is not viewed as shameful to lie there doing nothing. It is perfectly natural. That is the correct way to think about it.

Republicans are freaking out at the moment because (thanks in part to Bernie Sanders) some people at the lower end of the wage scale are currently getting more in unemployment benefits than they earned at work, and thus the employees are being “encouraged to stay home.” The Wall Street Journal quotes a restaurant industry executive whining that a line cook who ordinarily earns $640 a week is now collecting $1,016. “Why would anyone take a pay cut to go back to work?” the Journal editorial board asks. Of course, encouraging people to stay home and not go back to work right now is good, because we’re in a global pandemic, and employers should have to pay a hefty premium if they want workers back when working risks giving them Covid-19. But a big part of the right’s opposition to the lockdowns, and its desire to open up the economy again as quickly as possible despite the risks, comes from its staunch opposition to “paying people not to work.” (This is one reason they don’t like paid family leave, too.) There is a cult of work: We must produce, produce, produce, and if we are not producing we are bad. The “ethic” part of “Protestant work ethic” is important: Work is supposed to be a positive good rather than a necessary evil.

I do not think this way, because I have been to the aquarium. And I have watched schools of fish just go around in circles for hours and hours. They do not have a point. They do no work. They just exist. Plants are the same. It is not always easy being a plant, but there is a lot of down time. We should take much more of a cue from the flora and fauna that surround us. Once you have the basics, it is enough just to bask in the sunshine and potter around. And if your “contributions” dry up and you do crosswords all day, that’s okay too. You matter. The ducks matter. Even Ezekiel Emanuel matters, but not because of anything he produces. Life is beautiful in and of itself, and I do not need the old folks to produce scholarly papers in order to care about keeping them alive.

For more on this subject, see “In Defense of Laziness” in our Jan-Feb 2020 edition.