Looking Back At The Socialist Future

An excerpt from my future memoir, “My Affairs.”

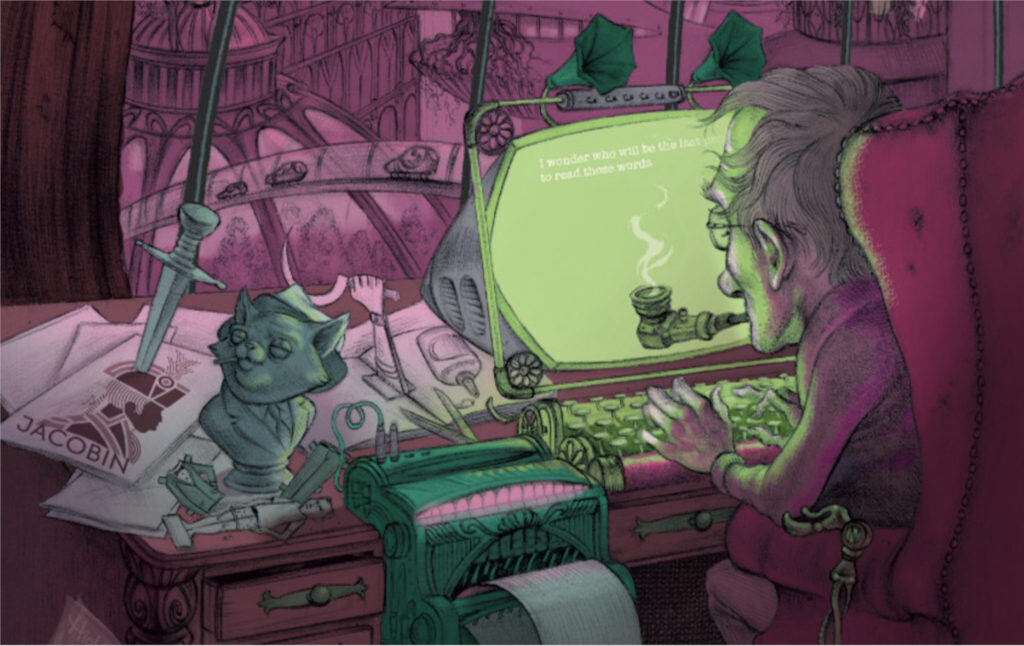

I recently released my memoirs, which recollect my six decades in the magazine industry. Because I have not yet lived for six decades (I am 30), I decided to write the autobiography from the perspective of my 87-year-old self, looking backward from the year 2076. The book, “My Affairs: A Memoir of the Magazine Industry (2016-2076) is available free online as a PDF, and can also be purchased in paperback form. (If you enjoy the free version, please consider making a donation to Current Affairs so we can make more of this sort of thing.) It is a semi-fictitious look at the history of Current Affairs, as well as the broader social changes that I assume will happen over the next several decades. You’ll find out what the Bernie Sanders presidency was like, who his vice president was, how Current Affairs ended up in a rivalry with Highlights for Children, what the New Cities looked like, how international borders gradually disappeared, and which year the last prison closed. It’s probably the strangest thing I’ve ever written (aside from Blueprints for a Sparkling Tomorrow) and I hope you’ll find it both amusing and inspiring. Some of it is a bit silly and implausible (such as my side-career writing bestselling novels about an anthropomorphic cat who edits a magazine) but I also wanted to provide a vision of a hopeful humane future that could offer people some consolation during bleak times. At least one person believes I successfully accomplished this; in Eric Blanc’s review of the book for Verso he calls it “a lovely and eccentric book, overflowing with food for thought and vivid descriptions of what a better world would look and feel like.” I hope you’ll agree. Here is a brief excerpt.

I never met Bernie Sanders myself. I did not think he would like me—Briahna Joy Gray, the White House press secretary and a former Current Affairs editor, had warned me that I was exactly the sort of person he would probably consider a “dilletantish fibbertigibbet.

“Bernie doesn’t like people he perceives to be morally frivolous,” she said, in explaining why she had thought it for the best to keep me out of a “left press meet and greet” held at the White House. “Besides, Current Affairs should maintain its editorial independence from the administration, don’t you think?” The next day, I received a note from Bhaskar expressing surprise that he hadn’t seen me at the meet and greet. In a fit of pique I tore it to shreds and set it alight. But I did not resent his success.

I respected Sanders from what I could gather at a distance—he declined to be called “Mr. President” and was Bernie to everyone, refused to accept salutes, abolished the playing of “Hail To The Chief” (to the consternation of the Marine Corps band, which switched to James Brown classics and New Orleans jazz-funk). But I was aware that our magazine should never become a propaganda mouthpiece for the President, and I was a scathing critic of many of his positions (the half-heartedness of his immigration reform, the skittish avoidance of the word “reparations,” etc.) Our job, we felt, was to nudge him ever further to the left, which we did through editorials like “A Profile In Cowardice: Why Won’t Bernie Say ‘Nationalize’?” and “Is Bernie Too Chicken To Take On The Military-Industrial Complex?” I am reliably informed that these annoyed him personally, an accomplishment I take great pride in.

I think what surprised people most, even those of us on the Left, was that the sky did not fall. Electing Sanders had seemed such a radical act, and yet life went on mostly as normal. The stock market wobbled and the capitalists were on CNBC all day threatening to take their money elsewhere, but Sanders was fairly astute and knew how to push only as hard as was in his power at any given time. Given clichés about socialist profligacy, one “surprise” was that Sanders was ruthlessly devoted to efficiency. Not austerity, which is quite different. But making sure the “end user experience” of government was a positive one: that the lines at the DMV were shortened, that people’s mail didn’t get lost, that tax forms were made easy to understand, that the Federal Register was pruned and simplified, that agencies spent their money well.

“This government belongs to the people, and the people must not only feel represented by it, but their experiences interacting with it must be positive ones,” Bernie said in his first State of the Union. “Ronald Reagan said that the most terrifying words were ‘I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.’ That was certainly true of Ronald Reagan’s government. But this government recognizes that when a person is in need, ‘I’m from the government’ means that the fire department has showed up, or that your Social Security check has arrived, or that social workers and teachers have come to help. We are determined that it should be a relief to know that your government is out there working for you.”

The range of measures that were signed into law in the first 100 days is staggering to look back on. A nationwide $15 minimum wage. An immediate halt to deportations. An increase to the minimum Social Security benefits. A full overhaul and upgrade of Amtrak, so that it would be a high-speed service to rival its counterparts in Japan and Europe. Mandatory paid parental leave. A network of free childcare centers, plus a monthly childcare allowance for every new parent. The massive expansion of free senior centers, to curb the epidemic of isolation and loneliness that so many older people were suffering in their final years. A comprehensive federal plan to tackle the opioid crisis (which would ultimately be in large part funded by the colossal settlements paid by drug companies). Beefing up the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau so it could harshly crack down on predatory lending. Prohibiting water shutoffs.

This was made politically possible by a few things. First, after it became clear that Bernie would be president, a great number of Democrats who had formerly opposed him suddenly discovered they had actually liked him all along. Just as the 2020 primary candidates had all adopted pieces of Bernie’s platform when it became popular, national politicians all raced to show they were “Bernier-than-thou” since this was clearly the direction of public opinion. Nobody wanted to be one of the Democrats who got in the way of the Sanders agenda, because he (and his legions of supporters) had made it clear that those who clung to “business as usual” would have targets painted on their back, with portions of the leftover Sanders war chest handed over to their primary opponents. It turned out that Congressional Democrats were mostly not actually “centrists”

so much as opportunists, and when a social movement shifted

the arrangements of political power, they, too, shifted. Hence

the fierce opposition that many predicted Sanders would face

never quite materialized.

Importantly, though, this was because Democrats knew there was an army of millions backing Sanders, one that would name and shame them if they dared to oppose, say, free college. Sanders also made it clear that there was a “carrot” along with the threatened stick: if you did vote for the bill, he’d be standing next to you at the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the next federal infrastructure project in your state, or the newest childcare center, a big smile on his face, talking about what a stalwart champion of the people you had always been, and how the people of your district knew they could depend on you to always do the right thing because that’s just the kind of person you were. And he’d say that he was so pleased that you had promised never to take any more Wall Street donations, even though you had never made any such promise, and as he walked off the stage he’d wink at you, knowing you now couldn’t possibly walk back the promise he had just made in your name.

This was all astute politics, but Sanders was still limited by the small number of authentic “radicals” in Congress. In retrospect, we had not done enough during 2020 to try to overthrow some of the Democratic dinosaurs who ended up derailing important reforms (Medicare for All, codetermination, etc.) Getting rid of Pelosi helped a great deal, but Charles Schumer hung around until 2022 making a nuisance of himself. It was not until the Red Wave of 2022 that we really managed to secure the kind of powerful majority that was necessary. I do wish we had started earlier, because it meant that the first two years of the Sanders presidency had to be dedicated in part to gathering the power necessary to fulfill important parts of the agenda in the second half. Those first two years were tough, because Sanders couldn’t do as much as he needed to do, and people were watching his presidency closely, many intent on declaring it a failure as soon as they could.

But, similar to what happened under the Labour government in the UK around the same time, the policies became bolder as time went on. In ’23 and ’24, private schools were abolished (actually, technically they still existed, but had to accept anyone who applied on a first come, first served basis and could not charge tuition). Amazon was nationalized and merged with the United States Postal Service to form the USODS (United States Ordering and Delivery Service, later a branch of the Global Parcel & Package Service), with parts of it like Amazon Web Services spun off into private, not-for-profit cooperatives. Medicare For All was finally passed, giving every single person in the United States free comprehensive healthcare (including vision and dental care), and abolishing the private insurance industry. (Many people in the industry were retrained as “patient advocates” and used their skills to badger doctors into giving patients better treatment rather than badgering patients into paying larger shares of their expenses.)

Reparations finally became a “politically viable” issue, and a bill was passed to study the question and determine what might be feasible. There were all sorts of difficulties, of course, over who exactly should be entitled to reparations and what they should get, but a pragmatic solution was reached: the necessary amount of “reparations” was defined as the sum total amount of the racial wealth gap between black and white people. So, we would know reparations had successfully been made when that wealth gap disappeared. (After all, unless one bought in to racist theories about culture or genetics, the racial wealth gap could be seen as the amount of financial damage caused by racism.) Then, a package of solutions was designed that would eliminate this gap within 50 years, not primarily by handing out checks but by targeting giant investments in Black communities and chipping away at white fortunes that had amassed over time. As we know, the target was not met, but we no longer see the truly extreme statistics of 50 years ago (in some cities, the average Black family had $8 in wealth while white families had hundreds of thousands of dollars). I am glad to see the Racial Justice Completion Commission at work on a serious solution for finishing our long, long overdue need to make full reparations.

As for myself, I had begun to devote a considerable portion of my time to the cause of non-human animals, who I considered the members of a kind of New Proletariat. Because they were unable to vote and didn’t own property (and we had not, at that point, figured out how to translate their thoughts), animals’ interests were then almost completely unrepresented, and they were slaughtered by the billions with barely anyone noticing or caring. I penned a book—a pamphlet, really— called The Rights Of Man (But For Animals). (The British title was simply The Rights of Animals, because British people are dull.) My argument in the book was that the entitlement of animals to pursue their interests was as presumptively absolute as our own, and that we had no natural right to murder and devour them. Provocatively, I compared the way that our society ignored mass industrialized killing of animals to the way that German society had ignored the mass industrialized killing of human beings, though I did not go as far as the controversial anarchist pamphlet The Meat Holocaust, which was denounced on the Senate floor.

These were heady times, with many things happening at once. The worker ownership plan was being implemented, with corporations distributing a portion of their stock to employees each year, steadily shifting the overall ownership ratio between rich shareholders and workers. New York Times columnist David Brooks was killed by a falling chandelier in flagrante delicto, and was replaced by leftist radio host Katie Halper. I received many office visits from subscribers, who consistently informed me that Current Affairs had been a comforting voice of reason in a time governed by sovereign madness.

My Affairs is a 200-page memoir looking back from the year 2076 at how humanity overcame its problems and worked together to build an extraordinary socialist utopia. It is available in the Current Affairs online store or (if you must) from Amazon. Cover art by C.M. Duffy.