Diversions of Empire: Narco-jihad in the U.S. Backyard

On the media, propaganda, and the alleged ‘secret connections’ between Latin American narco-traffickers and Middle Eastern jihadists.

On the last day of July, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (better known as ICE) tweeted out an alert for a “most wanted fugitive.” The target was one Tareck El Aissami, Venezuela’s Minister of Industry and National Production, whom the United States has branded a “specially designated narcotics trafficker” (“SDNT”). The tweet was accompanied by the hashtag #MostWantedWednesdays, lest anyone think this was not some serious shit. Twitter users were warned to “not attempt to apprehend [the] subject” on their own.

Notorious right-wing news site Breitbart quickly grabbed the ball and took off with it, proclaiming El Aissami the “Hezbollah ‘bag man’ running Venezuela’s oil industry.” The source of this particular allegation was the self-styled “terrorism expert” Dr. Vanessa Neumann, one of a coterie of characters currently dedicated to exploiting a lucrative niche: the forcible fusion of America’s international enemies into a single, terrifying monster, whose power and reach successfully provide a justification for U.S. militarism worldwide. Call it #WhackjobWednesdays(AndEveryOtherDay).

This strategy is not new. During the Cold War, the United States needed to portray communism as a direct threat to the nation in order to justify its policy of arming a cavalcade of right-wing dictators and death squads from El Salvador to Argentina. Back then, the communist monster was said to manifest itself in various ways—like the purported Sandinista-Palestinian-Soviet-Cuban-Iranian-Libyan-East German-Bulgarian-North Korean scheme to attack the United States from Nicaragua, dutifully exposed by Ronald Reagan in 1986.

Nowadays, some of the old nemeses remain, but the monster has shapeshifted to reflect today’s imperial interests in the so-called U.S. “backyard” and beyond. With both the Iranian government and Lebanon’s Hezbollah occupying a prominent position in U.S. crosshairs, what better way to help validate the brutal sanctions on Iran, U.S.-backed Israeli bellicosity, and other American machinations in the Middle East than by visualizing the Iranian-Hezbollah duo right on America’s doorstep? Even better when you can link them to Venezuela, or some other thorn in the side of empire.

Let’s start with the above-named “terrorism expert” Vanessa Neumann, a Caracas-born writer, political theorist, wealthy socialite, (and Mick Jagger’s ex-girlfriend), whose CV now also includes service as the “Official Representative of Pres. Juan Guaidó to the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, and the International Maritime Organization.” (Guaidó, of course, is the politician who spontaneously anointed himself leader of Venezuela in January 2019, but who has not yet managed to dispense with the actual Venezuelan president, Nicolás Maduro, despite financial and other encouragement from the United States.)

Neumann’s LinkedIn profile defines her as an “entrepreneuse” (seriously) “with extensive relationships to identify reliable partners and bridge relationships across Western Hemisphere industry and governments.” She also served the pre-Chávez Venezuelan oil industry, in addition to doing other cool things like being an “academic reviewer for the U.S. military’s Special Operations Command (SOCOM) teaching text on counterinsurgency in Colombia.” This year, her entrepreneuse-ship landed her in the spotlight at the U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee, where she argued against the Prohibiting Unauthorized Military Action in Venezuela Act on the grounds that Venezuela was “facing a massive starvation—that rivals that of Ethiopia, Somalia, and Darfur.” She also claimed that continued unrest would cause Venezuelans to flee the country, and those escaping citizens were likely to join up with ISIS in Trinidad and Tobago. “We [Venezuelans] have already been invaded,” Neumann declared, and “our slaughter is at the behest of nefarious foreign powers.” Hence, she argued, the United States should permit military action in Venezuela, because such “international assistance” could help wrest “territorial control” away from a bevy of “non-state armed groups” including the Colombian paramilitaries FARC and ELN as well as Hezbollah.

In a May article for Saudi Arabia’s Al Arabiya English website, Neumann threw herself wholeheartedly into her position as Monsterfinder-General, asserting that Maduro had allowed the finance department of Venezuela’s state-owned oil company to become a “money laundering mechanism for everyone from Iran to the FARC to Russian organized crime.” In particular, Neumann emphasized the “blood ties” that bound Hezbollah to Venezuela, in the form of “bag man” and SDNT Tareck El Aissami, who is of Syrian-Lebanese heritage (need we any further proof?!). Given—as Neumann insists—that Hezbollah and Venezuela are clearly partners in the drug trade, there’s a danger that Hezbollah would “seek to keep Maduro in situ through asymmetric or terrorist operations.”

But is there actually any evidence that Hezbollah is involved with drugs in Venezuela? Several media outlets including the New York Times have claimed as much, though FAIR, the media watchdog organization, has denounced the Times’ reporting in particular as unverifiable U.S. government propaganda. The historian and investigative journalist Gareth Porter told me some years back—with regard to U.S. efforts to bust Hezbollah in tandem with alleged Lebanese-Colombian drug kingpin Ayman Joumaa—that “the problem with the kind of declarations issued by U.S. officials vaguely claiming financial links between an alleged drug lord and Hezbollah is that they are completely lacking in transparency.” In other words, no real proof of collaboration is provided and there is absolutely no way to verify these claims. Porter contended that, “in the absence of more clear-cut evidence, one must suspect that the alleged link is nothing more than [the two groups] having some dealings with the same bank in Beirut.” Nonetheless, any allegations of narco-conspiracy between U.S. enemies tend to be treated in the media as unquestioned fact.

Hezbollah itself happens to be a devout Shia organization which claims to fiercely oppose sinful behavior such as, you know, drug trafficking. As Lebanese scholar Amal Saad, author of Hezbollah: Politics and Religion, commented to me, “the U.S. media and ‘terrorism experts’ who together make up the terrorism industry uncritically reproduce unsubstantiated allegations [from] official sources,” seeking in part to destroy what legitimacy Hezbollah may have “by detracting from its Islamic religious credentials and tarnishing it with drug money.”

Consider the 2017 denunciation of Hezbollah by House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Ed Royce (R-CA), who labelled the group “one of the top terror threats in the world,” and asserted that the Lebanese party was an entirely Iranian creation, which the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) had recently “implicated… in a multimillion-dollar drug traffic and money laundering network that spanned four continents and put cocaine ultimately on the streets of the United States.” Royce had encountered Hezbollah himself in 2006, when his visit to Haifa happened to overlap with Israel’s ruthless 34-day war on Lebanon. From Royce’s perspective, the primary victims were the Israelis: “There were 600 victims from Haifa in the trauma hospital who were being treated as a result of the [Hezbollah] attacks on civilian neighborhoods.”

Studiously left out of Royce’s crime scene report, however, were the Lebanese victims. The Israeli military slaughtered an estimated 1,200 people in Lebanon during the war, the majority of whom were civilians. And Hezbollah, it bears underscoring, didn’t materialize out of nowhere; rather, its origins lie in the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon that killed—according to much reliable reporting and to Noam Chomsky himself—some 20,000 Lebanese and Palestinians. In this case, too, the vast majority of the dead were civilians. In his book Pity the Nation: Lebanon at War, veteran Middle East journalist Robert Fisk recounts Israel’s phosphorus shelling of West Beirut that summer, when patients began arriving at Barbir hospital “still on fire.” He quotes one doctor on the predicament of five-day-old twins who were brought to the hospital dead: “I had to take the babies and put them in buckets of water to put out the flames. When I took them out half an hour later, they were still burning. Even in the mortuary, they smoldered for hours.” Royce does not mention any stories like this one, let alone label them as what they are: state terrorism.

As for the currently unverified accusation that Hezbollah has been “putting cocaine on U.S. streets”, this is perhaps a good time to bring up the United States’ extremely verified habit of putting cocaine on its own streets—and supporting what some might possibly call “narco-terrorism.” The most infamous example is of course the Contra episode of the 1980s, in which U.S.-backed right-wing militias engaged in what Noam Chomsky has described as “a large-scale terrorist war against Nicaragua.” These militias, as it turns out, were at least partially funded by cocaine smuggled into the United States. One of the results: a crack cocaine epidemic that devastated Black communities in South Central Los Angeles. (But hey, some streets are more important than others.)

The Contra episode was not the first of its kind. As one New York Times op-ed indicates: “The CIA Drug Connection Is as Old as the Agency.” Published in 1993, the essay describes “CIA ties to international drug trafficking dat[ing] to the Korean War.” During the Vietnam War, heroin from a refining lab in Laos was allegedly “ferried out on the planes of the CIA’s front airline, Air America… Nowhere, however, was the CIA more closely tied to drug traffic than it was in Pakistan during the Afghan War [referring here to the Afghan-Soviet war from 1979 to 1989]”. In Honduras in the 1980s, meanwhile, historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz recalls that SETCO, an airline owned by Honduran “drug king” Juan Ramón Matta-Ballesteros, was “dubbed the CIA airline.” Not only did SETCO assist in the Contra supply effort, “it also, famously, made drug runs.” And let’s not forget the CIA’s collaboration with drug-trafficking Cuban exile mobsters in efforts to assassinate Fidel Castro—or the CIA’s decision to conduct LSD experiments on its own unwitting citizens in the 1950s.

The list goes on. And yet, thanks to the beauty of imperial logic, the United States’ repeated partnership with known drug traffickers, from Panama’s Manuel Noriega (described by Reuters as a “CIA spy turned drug-running dictator”) to Colombia’s Álvaro Uribe (who, prior to becoming president of the country, appeared on none other than a U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency list of major narco-traffickers) has not at all impeded the deployment of a so-far unsubstantiated narco-accusation against Hezbollah.

As for why the whole “narco-terror” label has recently become so popular, it’s worth revisiting Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Ginger Thompson’s 2015 New Yorker report: “Trafficking in Terror.” In it, she quotes a former senior money-laundering investigator at the U.S. Department of Justice on how the post-9/11 transfer of resources “out of drug enforcement and into terrorism” meant that, for the DEA, narco-terror “became an ‘expedient way for the agency to justify its existence.’” In fact, the new crime of “narco-terrorism” was introduced in the 2006 iteration of the Patriot Act, and enabled the DEA to “claim… victories against Al Qaeda, Hezbollah, the Taliban and the FARC”—victories that naturally didn’t come without appeals to Congress for more money.

As Thompson documents, however, a close examination of the cases the DEA chose to pursue revealed a disconcerting pattern. “When these cases were prosecuted, the only links between drug trafficking and terrorism entered into evidence were provided by the DEA, using agents or informants who were paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to lure the targets into staged narco-terrorism conspiracies.” Proof—or the existence of actual narco-terrorist conspiracies—wasn’t essential. But anyway, at least the DEA didn’t go hungry.

Indeed, there’s no shortage of “experts” and analysts ready to swear to the powers that be in Washington that Hezbollah is in bed with this or that Mexican cartel. Tony Duheaume, author of such works as the self-published The Mullahs & Hezbollah – Iran’s tools of oppression & hegemony in the Middle East and beyond, warns that Hezbollah is “well-established in Mexico” and that “it has aligned itself to the ultra-violent Los Zetas drug cartel,” right in “Donald Trump’s backyard.” The Clarion Project, a D.C.-based organization that claims to “expose how Islamists…threaten Western values” cites testimony accusing Hezbollah of collaboration with the Sinaloa cartel—the very same Sinaloa cartel that, as a 2014 Time Magazine writeup detailed, secretly worked with the DEA for more than a decade. Oops. (The Clarion Project is mainly concerned with Islam, but their map of extremist organizations also includes anti-Muslim extremists, on the basis that “[t]heir activities unwittingly contribute to the Islamist cause.” It is very generous of the Clarion Project to conclude that Islamophobic bigotry and violence is also bad, if only because it makes Muslims more defensive of Islam.)

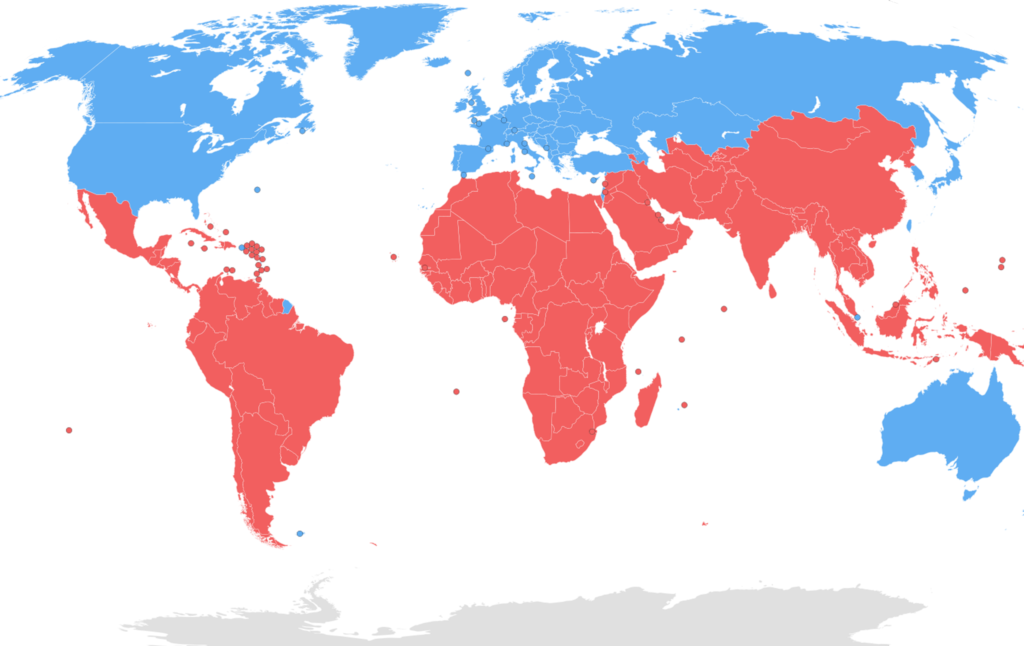

Other intriguing trivia trotted out in support of Hezbollah’s alleged links to the drug trade include that “Venezuela’s geographic proximity to West Africa make[s] it an ideal launching pad” for the transatlantic movement of drugs. This bit of wisdom was presented to the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations by former United Press International Bureau Chief in El Salvador Douglas Farah, who had perhaps not recently consulted a map. He’s since been one-upped on the creativity front by Nathan A. Sales, State Department Coordinator for Counterterrorism, who in 2018 broadcast the existence of a “Hezbollah pig farm in Liberia,” which, given the Islamic prohibition against eating pork, seems rather unlikely.

In a 2011 dispatch titled “The New Nexus of Narcoterrorism: Hezbollah and Venezuela,” the aforementioned “expert” Vanessa Neumann drew attention to a “main transportation route for terrorists, cash and drugs… aboard a flight commonly referred to as ‘Aeroterror.’” According to Neumann’s “own secret sources within the Venezuelan government,” Aeroterror’s flight route was Tehran-Damascus-Caracas-Madrid; it would “leave Caracas seemingly empty (though now it appears it carried a cargo of cocaine) and returned full of Iranians, who boarded the flight in Damascus, where they arrived by bus from Tehran.” It was not explained why the Iranians couldn’t simply have boarded the plane in Tehran rather than sit on a bus for 1,747.8 kilometers (a 20-plus hour trip).

To be sure, the possibility of air travel between Caracas and Tehran has long been a point of obsession for those concerned with the new Islamo-Socialist-Narco-Jihadi Menace. Back in 2009, Israeli Deputy Foreign Minister Danny Ayalon sounded the alarm: “We know that there are flights from Caracas via Damascus to Tehran.” Precise details, though, have tended to vary from fearmonger to fearmonger. In a 2011 Fox News piece entitled “Hugo Chávez’s Scary Anti-American Campaign Takes to the Skies and Stops Off In Tehran,” Roger Noriega—the former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State and current fixture at the neoconservative American Enterprise Institute—made a claim that the Venezuelan airline Conviasa was responsible for operating “Aero-Terror.” Linking Caracas, Damascus, and Tehran, the flight was said to be “a critical tool for Iran and Venezuela and their allies among terrorists and drug traffickers”—transporting “Hezbollah recruits from throughout South America” and “components for missile systems.” The arrangement sounded decidedly less scary in a 2007 WikiLeaked cable from William R. Brownfield, then-U.S. Ambassador to Venezuela, stipulating that the Caracas-Tehran flight was “best understood as a symbolic manifestation of the cozy Chávez-Ahmadinejad alliance” and that its inauguration “provided a stage for both Iran and Venezuela to thumb their noses at the United States.” Brownfield would go on to become Assistant Secretary for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs.

Roger Noriega, for his part, was also the brain behind the 2010 Foreign Policy exposé about “Chávez’s Secret Nuclear Program,” in which we learned that “it’s not clear what Venezuela’s hiding, but it’s definitely hiding something—and the fact that Iran is involved suggests that it’s up to no good.” Unfortunately, WikiLeaks would play the party pooper here too, thanks to a cable authored by John Caulfield, the U.S. embassy chargé d’affaires in Caracas: “A plain-spoken nuclear physicist told Econoff that those spreading rumors that Venezuela is helping third countries (i.e. Iran) develop atomic bombs ‘are full of (expletive).’”

Then there’s the version of “Aeroterror” and other threats provided by Matthew Levitt of the exuberantly pro-Israeli Washington Institute for Near East Policy. In his 2013 book Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God, he contended that Iran Air flight 744—this time operating between Caracas and Tehran, with stops in Damascus and Beirut—functioned as a delivery service to Venezuela for members of Hezbollah, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, other “Iranian agents” and intelligence personnel.

With his Global Footprint, Levitt has done us the dubious favor of amassing in one place all of the kooky talking points on narco-terror and related subjects—an encyclopedia of propaganda, as it were. Among the greatest hits is the issue of narco-tunnels. Because “the terrain along the southern US border, especially around San Diego, is similar to that on the Lebanese-Israeli border,” Levitt writes, drug cartels have “enlisted the help of Hezbollah” in the art of cross-border tunnel construction. Never mind a New Yorker investigation into narcotúneles in the San Diego area, the first of which was built by the Sinaloa cartel in 1989 (i.e. when Hezbollah was tied down in Lebanon with the civil war and Israeli occupation): “Since then, Sinaloa has refined the art of underground construction and has used tunnels more effectively than any criminal group in history[,] specializ[ing]… in infrastructural marvels that federal agents call supertunnels.” Hezbollah is nowhere to be seen.

“Relatedly,” Levitt continues, “law enforcement officials from across the Southwest are reporting a rise in imprisoned gang members with Farsi tattoos”—a military-cultural analysis of which U.S. Representative Sue Myrick (R-NC) had performed back in 2010, when she determined that the body art on gang members “implies a Persian influence that can likely be traced back to Iran and its proxy army, Hezbollah.” (There are no other potential explanations offered, including the possibility that these gang members just believe that Farsi looks cool). The Tucson Police Department, Levitt stresses, also detected “alarming implications” of these tattoos “due to Hezbollah’s long standing [sic] capabilities, specifically their expertise in the making of vehicle borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs)”—since, as everyone knows, it’s a slippery slope from tattoos to explosions. And if this weren’t enough, a clothing patch was also discovered near the U.S.-Mexico border depicting “a plane flying head-on into skyscrapers.” But as even the narco-hysteria-prone website InSight Crime noted around the same time, “reports of Hezbollah working with criminal groups in Latin America… appear to be largely unsubstantiated.”

Meanwhile in the world of Levitt, not only does Hezbollah preside over a “foothold in Mexico”, the organization has also set up shop in the United States proper, where it has been linked to “food stamp fraud, misuse of grocery coupons, and sale of unlicensed T-shirts.” At the very least, T-shirt sales must be a nice change of pace for Hezbollah from activities back home, where cross-border incursions by the U.S.-backed Israeli military have included a brutal 22-year occupation of south Lebanon and periodic massacres of civilians. (The last major showdown was back in 2006, but Israeli officials continue to devote much time to warning of bigger and better wars yet to come.)

But again, reality is not what we’re after here. The goal, rather, is to convert Hezbollah/Iran into a direct, existential threat to the homeland itself, and to thereby encourage an increasingly antagonistic U.S, foreign policy vis-à-vis international obstacles to empire. Granted, it’s not like Donald Trump requires much help in the realm of these connections, having already detected swarms of “criminals and unknown Middle Easterners” mixed up in that “National Emergy” [sic] known as the Central American migrant caravan. Who knows how many of these migrants might have been sporting a plane-into-skyscraper clothing patch?

Other members of the Trump crowd have delivered similarly stellar performances. In February, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo informed Fox Business that, not only had “the Cubans invaded Venezuela,” Hezbollah also possessed “active cells there,” with the “Iranians… impacting the people of Venezuela and throughout South America.” The upshot: “We have an obligation to take down that risk for America.” The following day, it was the turn of U.S. Southern Command Admiral Craig S. Faller, who warned the Senate Armed Services Committee that Iran’s “proxy Lebanese Hezbollah maintains facilitation networks throughout the region that cache weapons and raise funds, often via drug trafficking and money laundering.”

And yet despite the continuous churning out of breathless reports about Hezbollah’s “multimillion-dollar drug-trafficking business in Venezuela with the collaboration of FARC and Mexican cartels”—or Iran and Hezbollah’s ability to smuggle “drugs, arms, and, if necessary, chemical and biological weapons” across the U.S.-Mexico border—the Trump State Department itself reported in 2018 that there was “no credible evidence indicating that international terrorist groups have established bases in Mexico, worked with Mexican drug cartels or sent operatives via Mexico into the United States.”

As for that “most wanted fugitive,” Venezuelan minister and SDNT Tareck El Aissami, the New York Times has taken it upon itself to reveal some tantalizing “Secret Venezuela Files” passed along by undoubtedly impartial observers “recount[ing] testimony from informants accusing Mr. El Aissami and his father of recruiting Hezbollah members to help expand spying and drug trafficking networks in the region.” At some point in the piece, we learn that, actually, “whether Hezbollah ever set up its intelligence network or drug routes in Venezuela is not addressed in the dossier,” but it’s safe to surmise that’s not the takeaway the average reader will extract. In the FAIR post about the New York Times’ uncritical repetition of U.S. government propaganda, the authors point out that the Times piece even “admits that Washington ‘never revealed the evidence’” of El Aissami’s allegedly neck-deep involvement in the narcotics trade. Nevertheless, bit by bit, the case for future U.S. wars on narco-terrorists grows stronger, normalized and justified in the public consciousness, simply by constant repetition of unsubstantiated claims.

Speaking of drugs, the late Québécois journalist Gil Courtemanche once wrote: “Propaganda is as powerful as heroin; it surreptitiously dissolves all capacity to think.”

Isn’t it time, then, to consider trafficking in propaganda a crime?