Breaking Development

Our concept of “development” is destructive and irrational. It must be abandoned.

Summer 2018

- The U.S. National Science and Technology Council declares that the country is unprepared for an asteroid impact, like the one that killed off the dinosaurs.

- The USNSTC releases the National Near-Earth Object Preparedness Strategy Action Plan, which, it should be noted, the dinosaurs likely failed to do.

- Atmospheric CO2 hits a record high (407ppm).

- Extreme heatwaves strike basically every continent, scorching the earth with “unprecedented” wildfires.

And I decided it was a good summer to take a drive with my partner around Florida. Early in our trip, we stayed in Safety Harbor, in the bedroom of a real estate agent’s home. The day after we left, the town was partially evacuated due to a colossal cloud of the biblical-sounding “red tide”—toxic gas belched out by an uncommonly potent algal bloom. Such events are becoming more common, exacerbated by pollution from agricultural runoff and human bodily waste. We decided to go to the Everglades.

Having only ever seen the Disney-owned part of Florida growing up, I had a lot of fanciful ideas about what the Everglades were like: lush jungles and teeming swamps. Like Yoda’s planet. After all, the Everglades was once a huge subtropical ecosystem, and though it has been dramatically shrunk by encroaching rich-person activity, like golf and chintzy mansions, it is still the largest subtropical wilderness in the U.S. It houses many rare, endangered species. 2018 was also the year Florida boaters broke the record for number of manatees they killed; they would break it again in 2019. Boaters killed 130 members of this gentle, harmless endangered species, a number that has been rising every year since 2016.

We arrived at a fairly quiet entrance to the Park, and, to my disappointment, one with no Giant gate with torches on either side. Strolling on a paved path, there was little wildlife that we could see. It was too hot for most of the gators and crocs, we’d later learn, who rest at the bottom of the water to escape such heat, and for the birds who hadn’t migrated back yet from wherever they had flown in this summer’s broken climate. We did hear the eerie call of a lone limpkin pierce through the relative silence, and caught a glimpse of a purple gallinule, a special siting of a “rare Jesus bird” according to an older man passing by (they’re not very rare in the Everglades, according to the internet).

We left the path and took a narrow trail into the thick, stunted forest. There’s a thrill you can only get stalking through a forest knowing there are large, dangerous animals sharing the wood with you. Winding through tangled branches with standing water creeping up our legs, we found only mosquitoes (a pest that thrives in a warmer world). Once their biting through our clothes became too much—West Nile virus not the sort of danger we sought—we turned back the way we’d come. Back on the pavement we came upon a family of tourists peering into the dense trees from which we had recently emerged. In a nondescript-probably-Romance European accent, the father alerted us to the massive reptile (link to a personal video) that sprawled just within the shade.

This swarthy patriarch nonchalantly pulled at some of the branches shielding the gator, his small children and me inching ever closer to the resting reptile whose close ancestors predate dinosaurs (“dinosaur” may mean “terrible lizard,” but “alligator” means The Lizard). I couldn’t help but imagine one of the children, whose ancestors were tiny monkeys and much newer to Earth, being easily snapped up and swallowed in one gulp. A loud snack. The father pulled at the shrub and the gator suddenly lurched and snapped at us, and only the padre di famiglia jumped back. A Park Ranger passing by on the child of a train and golf-cart told us She was a particularly aggressive alligator and that we should not go near Her.

Later, a French-speaking family gathered on a small boardwalk to peer down at a different, maybe more docile, gator. The patriarch of that family began dropping large sticks on the reptile. His wife and kids walked away.

Perhaps the Everglades fell short of my childish expectation, but we were grateful to have enjoyed the increasingly rare experience of glimpsing wildlife. These days, one must tour through the less developed areas of the country to find any wild megafauna. But even the Everglades, like many other parts of the country, risk being rapidly developed. The Trump administration has recently removed protections for half the nation’s wetlands and waterways as a handout to at least three kinds of developer: agricultural, fossil fuel, and real estate. The changes allow landowners “to dump pesticides into waterways, or build over wetlands, for the first time in decades.” When Trump announced these changes to the American Farm Bureau Federation in Texas, he received “raucous applause.”

Eliminating rules regulating, in this case, air and chemical pollution, coal and oil extraction, and protected endangered species was done, as always, in the name of development.

Development—developer / developed country / developing country / “development” as used today in economics, business, IR, or even colloquially, carries with it a connotation of progress. Development proceeds—advances!—with an untouchable, inevitable momentum. The word slips off the greasy tongue of a real estate developer or a single-minded investor or an impressionable business student with a lilt suggesting that even if you wanted to stop it, you couldn’t stop it—but you don’t want to stop it because look at this shiny new candy vape shop strip club mall concentrated liquified natural feedlot gas processing facility.

The evolution of the word can be traced from a Latin origin, to the French meaning “unfurling” in the 17th century, to “bring out the potential in” by the 18th century, and “advance from one stage to another toward a finished state,” in the 19th. Today, to develop is to transform land that was shared by many forms of life into land that is used by only one form of life. The process of turning land shared by many species into land dominated solely by ours, exclusively for the enhancement of ours, is progress.

This process of development and dominant idea of “progress” are intimately intertwined. This idea of progress is central to the nation’s founding mythology. It’s the story we tell about both our origin and our destiny. Development, meanwhile, is the practical implementation of that myth: the messy execution of the lofty notion. Progress is a Tale of the Plagues of Egypt in the Book of Exodus. Development is the modern plague of fecal-fueled red tide.

Modern liberal notions of progress in social, technological, and political change emerged during the European Enlightenment (1650-1800). Embedded in Enlightenment thought was not simply the belief in the value of scientific discovery and classical liberalism, but also in the intrinsic nobility of Western Civilization®. Enlightenment notions of progress helped to rationalize the belief in European conquest as an important mission spreading scientific knowledge, Christian morality, and good governance. By framing this conquest as natural, inevitable social progress that would advance humanity toward some finished state (an end of history, if you will), it was easy to justify even the most brutal tyrannies and some of the most ugly atrocities humans have ever committed. These ideas of progress came at a superb time for explaining why it was Good, Actually, for newly “discovered,” already-inhabited-by-humans lands to be viciously dominated—hm, developed—by Europeans. Suddenly “progress” could explain why the people already residing in these lands should not govern themselves, and why, instead, the “superior race” ought to govern them: It was for the good of humanity. And not only that, it was impossible to do otherwise. There was no alternative. It was Logic itself. To deny its inevitability was to reject reason.

A parallel attitude fueled the frantic rush to taxonomize all the new species colonists were “finding” and killing (developing). Darwin’s high-minded study of Galápagos tortoises, for example, occupies a mythologized place today as a prime moment of scientific Enlightenment progress. The less frequently told story is that those tortoises were nearly eaten to extinction by sailors because they could be easily kept alive on a ship and tasted good. Darwin himself ate his most prized specimen. The surviving population is now less than 10 percent of what it was before Darwin’s time.

Notions of superior Western development are often factually false. It should go without saying that it’s absurd to believe European society was at a more advanced state of progress than, for example, First Nations societies in the Americas. But it can’t go without saying because so many people take it for granted, in 2020. The superior nutrition—and thus physical health—of many First Nations people contrasted with European settlers is one clear, quantifiable way in which European civilization was no more (and, really, much less) advanced. But it’s not the only way. Also consider the many documented attempts of European settlers to defect to the Nations because of unbearable living conditions in the colonies. Consider the advanced, empirical systems of indigenous knowledge—medical, dietary, physical, ecological—that already existed long before the arrival of Europeans and were more suited to their environments. Consider the more egalitarian means of decision-making practiced by many (though not all) First Nations governments. Or, perhaps most relevant to this discussion, consider the more virtuous and rational means by which First Nations people interacted with other forms of life. A recent study in Nature Sustainability suggests that the indigenous people living in the current Northeastern U.S. had little impact on their environment in their 14,000 years residing there. (For perspective, “Western Civilization” has only required a couple hundred years to destroy North America’s environment.) There is, and was, no good reason to believe that Western Civilization was superior to the civilizations already inhabiting the Americas, or any of the other places European investors and developers plundered. That doesn’t mean we need to glorify indigenous groups or paint them as utopian. Foisting a “Noble Savage” caricature on indigenous people is dehumanizing in its own way, and we must be cautious not to crudely romanticize, or carelessly generalize on, First Nations people or any other groups. Still, it’s difficult to argue with the historical facts that seem to suggest: By many important measures, European civilization was not only not superior, but inferior to many of the civilizations settlers displaced. But don’t take it from me; take it from Ben Franklin: “No European who has tasted Savage Life can afterwards bear to live in our societies….Such [indigenous] societies provided their members with greater opportunities for happiness than European cultures.”

Many indigenous people today rightly balk at the idea that their cultures represent an earlier stage of development, particularly when they have been so superior to Western cultures at, among many other important metrics, healthfully inhabiting the planet that liberal economies are now destroying. American progress was the idea that justified their murder. Joseph Conrad articulates this justification like this:

“The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much. What redeems it is the idea only. An idea at the back of it; not a sentimental pretence but an idea; and an unselfish belief in the idea—something you can set up, and bow down before, and offer a sacrifice to…”

* * *

The first engagement the United States had with the Everglades was during the Second Seminole War (1835-1842). Andrew Jackson’s administration, riddled with many such atrocities, sought to colonize the peninsula and drive the First Nations Seminoles from the land. Of all the many First Nations Wars in which settler militaries engaged in combat and theft from Native Americans, this one stretched out the longest. As Jackson justified it to Congress:

“What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than 12,000,000 happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization and religion?”

After fierce resistance, the war finally culminated with the U.S. military forcibly removing between 3,000-4,000 Seminoles from their land. After clearing away inhabitants inconvenient to development, the United States’ relationship to the Everglades was entirely one of careless destruction. Starting in the latter 19th century, the U.S. launched a massive project of draining the Everglades for agriculture and new building. In 1912, developers sold 20,000 plots in months. 5 million Florida birds were killed for feathers. After more than a century of intensive extraction and destruction, the National Park was finally established in 1947 to protect what remained (to determine how successful it is at protecting life, you may want to ask some manatees). The project of establishing the Park was spearheaded by none other than a real estate developer. These meager conservation efforts may lead us to wonder whether National Park systems often serve as indulgences that help to ease the conscience—or at least mitigate the political backlash—against those driving the ever more ruthless exploitation of everything not Park.

Industrialization, and its acceleration via fossil fuels, would come to dominate the 19th and 20th centuries and seemed to confirm self-satisfied European Enlightenment notions of progress. Herbert Spencer was one of the 19th century’s most important social theorists promoting this liberal concept of progress. Though he isn’t such a big name these days, he became “the most famous philosopher of his time,” and “the single most famous European intellectual in the closing decades of the nineteenth century.” His ideas played an exceptionally important role in guiding the intellectual course of the era. Perhaps his most enduring contribution to human thought is the phrase “survival of the fittest.” Contrary to popular wisdom, the idiom was not coined by Darwin to describe natural selection, but instead invented by Spencer to advocate for his concept of sociobiology, a specific idea about how society should develop.

Despite some of his early-career radicalism (claiming not to love the idea of private property and considering himself rather feminist, for instance), Spencer was a classical liberal to the bones who thought the poor generally got what they deserved, and that European settler society was evolving toward a perfect state and “perfect man.” His legacy has been most emphatically taken up today by libertarians and neoliberals, but also by eugenicist race scientists and national socialists in the past. Central to his view of human progress was the imperial project of exterminating what he viewed as “lesser races.” Winston Churchill was one of many 20th century statesmen to articulate Spencer’s worldview explicitly, in terms that perfectly distill the European colonial mindset:

“I do not admit that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America, or the black people of Australia . . . by the fact that a stronger race, a higher grade race . . . has come in and taken its place.”

Such modern notions of progress and development cannot be viewed separately from fossil fuel development. Fossilized energy, an accursed gift bequeathed from past mass extinctions, was the material lifeblood flowing in the veins of these ideas; coal was the philosophers’ stone that would transform such intellectually bankrupt bullshit into gold. Fossil fueled machines, during the latter 19th and 20th centuries, dramatically hastened the imperial project of exterminating both indigenous people and species with, or without, market value, enabling the exponential acceleration of development to an increasingly frenetic pace. Fossil fuel machines moved goods and people faster and farther. They manufactured weapons more prolifically. They pushed buildings higher and higher into the sky, and sprawled them further and further afield. They expanded farms across ever more acres, while petroleum-powered tractors and synthetic fertilizers allowed proportionally fewer farmers to harvest the swelling acreage. And they empowered those empires that could control fossil energy flows to consolidate their grip on global politics.

The New Deal, often seen as a leftist incursion in this history of liberal progress, should more realistically be seen as a compromise with an agitating left, as a further extension and acceleration of liberal progress, and an important precursor to the second laissez-faire era that came next (an important lesson for Green New Dealers to internalize). The oil crisis of 1973 helped spark the rise of a sequel to the 19th century social Darwinism that drove fossil fuel industrialization and settler violence. A mode of capitalism that substantially resembled Spencer’s arrived just in time to rationalize a newly accelerated pace of development. Like the 19th century version of social Darwinian, laissez-faire liberalism, this new liberalism served to hide the destructive means behind seemingly virtuous ends. What’s perhaps even more insidious about this more recent iteration than the last is the absolute assurance so many feel that there is no alternative, that this version of living in the world is the height of human civilizational potential. And though Francis Fukuyama, the author of perhaps the most famous book articulating this view, The End of History, has himself disavowed his own argument, the belief that historical struggle for better ways of living really has ended with the victory of liberalism endures in virtually all of our most powerful institutions.

The short legacy of this second-wave of laissez-faire, fossil-fueled economic liberalism has been catastrophic. Since its inception in the 1970s:

- 60 percent of vertebrate populations have gone extinct.

- A vast majority of humanity’s total greenhouse gas pollution has been emitted.

- Two-thirds of tropical primary forests have been destroyed.

- Ocean fish numbers have been cut in half.

- 400, or 30 percent (or more), of remaining indigenous languages have been lost, and with them lives, cultures, and ways of living in the world.

- And wealth inequality has grown dramatically, returning to prewar extremes.

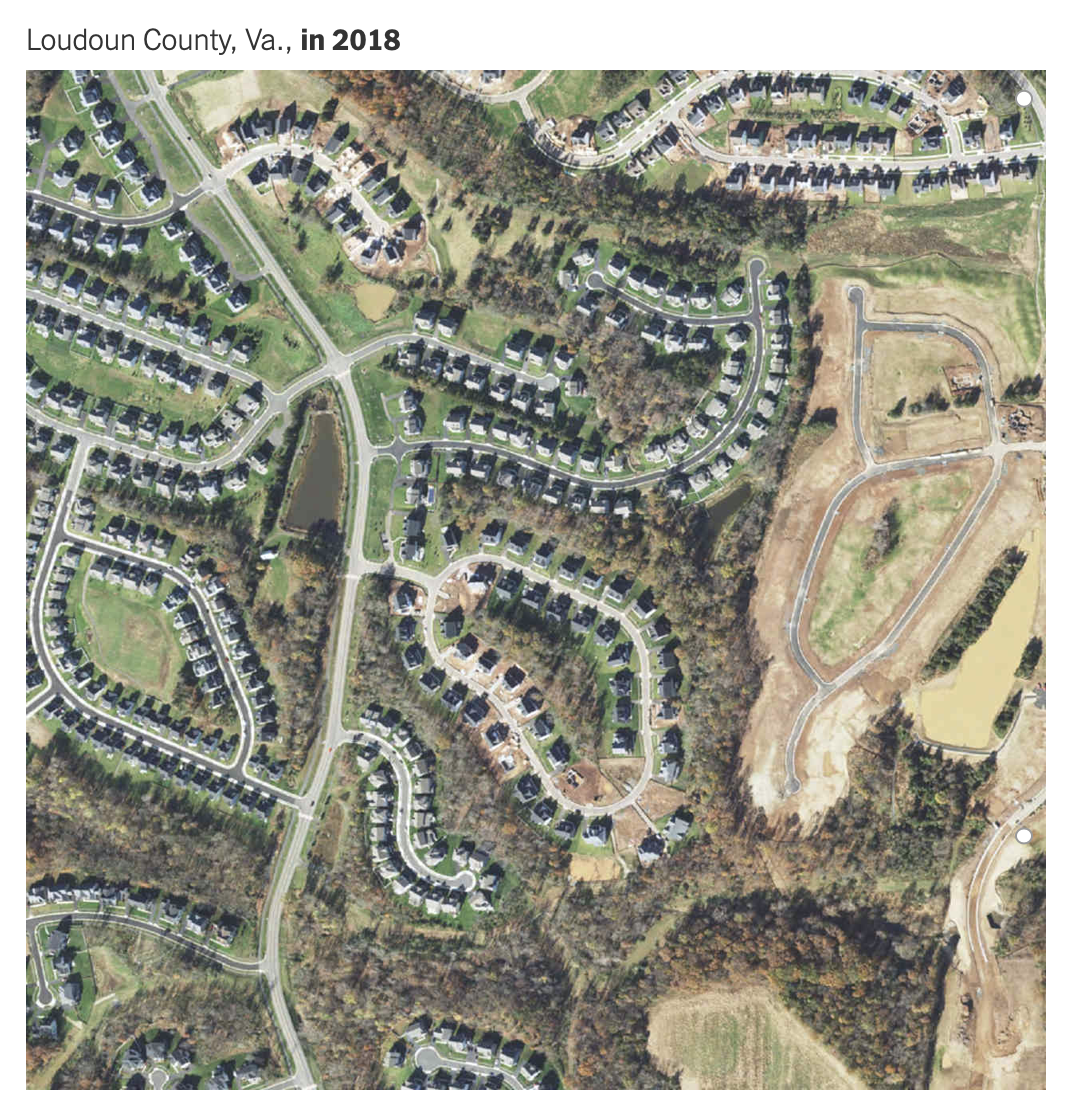

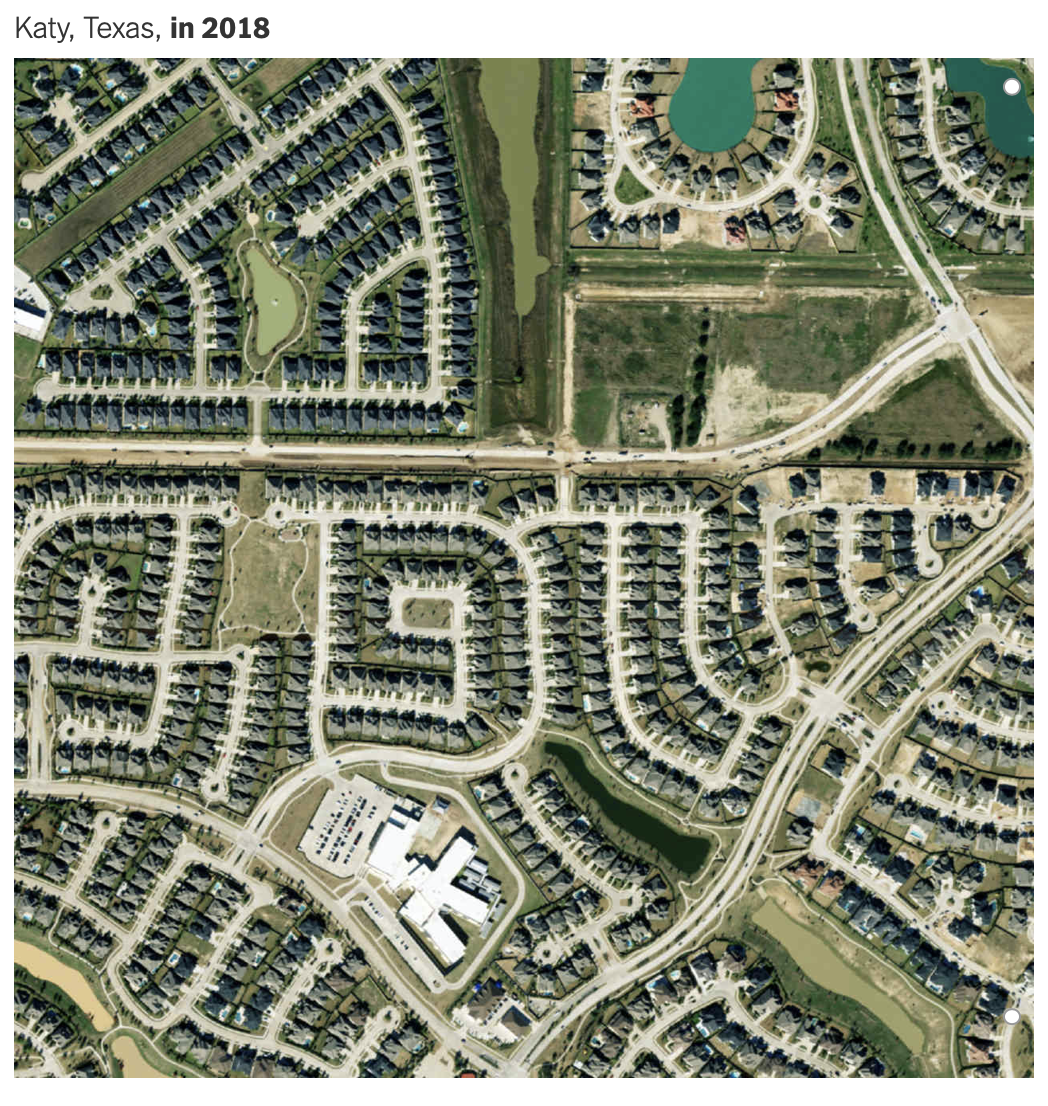

But these are just bullet points. For a sense of the pace at which liberal development is destroying nonhuman life, take a look at some side-by-side satellite photos assembled by the New York Times that have occurred within six to 10 year time spans:

Or take a look at these vast new urban spaces, top-to-bottom in BoredPanda:

Or look at this deforestation…

From PLOS (Borneo):

This is the direct result of liberal notions of development and progress, fueled by the fossilized carbon currently heating the world to death. Now project it out five more years, 10 more years, 50, 100.

In our very brief history on earth, there is one kind of linear progress that Homo sapiens can fairly be said to have achieved. It is not progress toward human betterment. The shift from a world of diverse, often abundantly prosperous, foraging and semi-agrarian societies to a world of less diverse agrarianism resulted in long millennia of increased malnutrition, poverty, and servitude, from which many have only begun to recover, and only haltingly. It is not progress toward greater knowledge, as so many vast knowledge systems have been destroyed, lost forever, and as so many still cling to long-disproved notions or to pseudoscientific superstitions like neoclassical economics.

The optimist might call our only form of forward momentum “technological progress,” but the realist understands that it is not the progress of a technology bent toward human or animal thriving. It is a technological progress that has gone toward transforming ever more land, ever more biomass, ever more energy toward ever-increasing absolute numbers of humans, but in ever-decreasing proportions of human thriving. Nor has this progress been a natural evolution through which all societies have proceeded. It is a notion of progress that has been imposed by a small class upon a great mass with absolutely ruthless violence.

And though it is reasonable to heap a large share of the blame on a small European aristocracy or the Western rich for all the murder and mayhem of development—and that is most assuredly the gravest enemy of the moment—the archaeological record of the species can appear fairly bleak, too. One kind of progress human beings have achieved is that of successive extinctions: 4 million years ago, our close ancestors initiated a major megafaunal extinction event, launching an ongoing worldwide decline in biodiversity. After anatomically modern humans evolved around 300,000 years ago, they likely began a process of exterminating other Hominids (great apes similar to us in intelligence and social organization). By around 30,000 years ago, Neanderthals were extinct and Homo sapiens likely remained the last of the Hominids. Between 15,000 and 10,000 years ago, during the transition from the Pleistocene to the Holocene, humans contributed to the Quaternary extinction event, which killed off much of the megafauna—fabled giant sloths and mastodons, for instance—that persisted around the globe. Today, fossil liberal progress and development is driving the sixth mass extinction, the greatest extinction event on Earth since the meteorite that caused the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction 66 million years ago and killed off the dinosaurs. Is progress toward mass death simply our destiny? Can we not help ourselves from seizing land and life from everything not human, or from everyone not insatiably greedy?

Donald Trump has more than once been called the Developer-in-Chief. This gilt monstrosity is in some ways a too-perfect embodiment and culmination of liberal progress. Herbert Spencer’s perfect man. A social Darwinian billionaire who believes in Spencer’s eradication of “lesser races,” whose dense, pallid flesh is composed mostly of the CAFO-farmed meat grown on vast tracts of former rainforest and sold at McDonald’s, whose hand-me-down career has consisted of hysterical construction projects erecting gaudy towers on the concrete shell encasing Manhattan’s primordial swamp, or on the fill in Florida’s contemporary wetlands, or destroying the Aberdeenshire dunes not so far from his ancestral homeland to lay down a golf course on which other wealth hoarders may conspire on their next development scheme; whose every impulse, every twitch and gesture, every errant word or garbled, mumbled homily or insult is calibrated perfectly to achieve the continued transformation of nonhuman life into the delivery of his bodily pleasure. Before he was President Donald Trump and still just “Atlantic City mogul Donald Trump,” this loudly avowed fan of Andrew Jackson and Winston Churchill tried to prevent Native-owned casinos from competing with his casinos in New Jersey. Survival of the fittest.

If you believe nonhuman life has intrinsic worth—or even just instrumental worth—there is no other rational course but to conclude that virtually all continued “development” is harmful. Put simply: If you believe life is good, development is bad. Removing indigenous people from their land was always evil. But the Enlightenment tales of inevitable moral progress succeeded in mollifying pangs of guilt, or political pushback, rulers may have felt. Those very same fantasies persist today. They continue to rationalize the mass extinction of wildlife and indigenous people ongoing right now, and the global ecological collapse driven by social Darwinian notions of progress. Look no further than “ecomodernists” who continue to trumpet “fantasies of endless growth” (in Greta Thunberg’s words), whose only contribution are market-oriented policies that have been proven not to reduce emissions, but to fortify the same liberal myths of progress now destroying all life. Teetering as we are at this precarious edge of mass extinction and millennia-long climate chaos, there can be no benign or benevolent development. There is no “green” development; it doesn’t matter if it’s solar panels or LEED-certified buildings. Any further development that displaces wildlife and marginalized people is an evil contributing directly to the annihilation of the possibility of life on Earth. Until we abolish liberal notions of development as progress, this mythology will continue to justify our death march.

Recently deceased Scottish author Alasdair Gray explains why through a character in his novel Poor Things. The character, a prodigious medical researcher who has worked miracles through his science, proclaims:

Selfish greed and impatience drove me and THAT…is why our arts and sciences cannot improve the world, despite what liberal philanthropists say. Our vast new scientific skills are first used by the damnably greedy selfish impatient parts of our nature and nation, the careful kindly social part always comes second.

This fact is becoming all too obvious to bear. The myth of development progress struggles to compete with the harsh reality of mass extinction and daily climate catastrophe. In order to maintain this myth of progress, liberal democracies have begun to elevate people willing to commit great evil to continue its legacy unto its own, and our, demise. Psychopathic heads of state like Bolsonaro, Boris Johnson, and Trump are simply necessary evils to continue the modern liberal project of development. Mainstream liberal commentators may balk at their coarseness and vulgarity, but as long as they believe in Enlightenment development progress as a continued project of transforming the world toward fulfillment of (mostly elite) human needs, they will continue to support the Bolsonaros, Johnsons, and Trumps. They must believe progress is Gast’s benevolent, supple Aryan cherub with a boob nearly hanging out delivering freedom, or a white lab coat summoning from a plastic test tube a perfect utopia, to sustain their understanding of reality and the virtue of their own existence. They must not acknowledge the actual reality that their progress is the Second Seminole War, the paving of the Everglades, and a bored Frenchman dropping sticks on an alligator. Despite its inevitable inundation by sea-level rise already making itself concretely felt in the form of constant floods, development in Florida’s liberal bastion of Miami continues to charge fullsteam ahead. Florida sinks and their only solution is more development, layers and layers atop a vast Seminole graveyard.

If only Gast’s pasty giant would turn around, she may see what Walter Benjamin’s angel of history* glimpses:

His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

Is death our destiny? The only option before us is to turn away from this myth of progress and putting something else in its place. The left’s great task today is not merely implementing a more just agenda within the prevailing framework, but also imagining in detail what a wholly different conception of material progress should look like. This is a much more difficult, complex task than it may seem. What it entails is not just the vast redistribution of material prosperity, but reconciling that prosperity with the fact that the seemingly untouchable momentum of development not only must slow; it has to stop and it has to reverse. The destructive progress that has characterized much of human history—and European, fossil fuel liberalism most histrionically—must somehow be halted. What the left program must figure out now is the best way in which civilization—the economies, businesses, real estate developers, political institutions, cities and farms—can equitably retreat and rewild.

To rewild a place entails dismantling much of the human infrastructure there, whether urban or agricultural, and letting it heal, either without intervention or with indigenous cultures’ participation. The undeniable ecological fact staring us in the face is that vast tracts of existing human-use lands, urban and rural, must be returned to wilderness. Over and over we see that removing development from a place allows wildlife to quickly return. Just 30 years after humans forced themselves from the area with their own irradiated fallibility, even Chernobyl has become a haven for rare and endangered wildlife, including eagles, lynx, and wolves. What a new left version of progress must entail is embracing the maturity to withhold and forego, collectively, and nurture other life, all while redistributing the riches of past development from an elite class to the many. If we are able to exercise the will, agency, and the virtue—and force those with power—to remove many of our edifices from the places they’ve drained and filled, and allow other forms of life to once again thrive, we may get to witness the spectacular abundance and majesty that some of our ancestors beheld, and that many cultures not infected with the disease of liberal development once beheld. We will either come to understand development and progress in this way, one that promotes the flourishing of all life, or we will have none. There is no alternative.