Rock Bottom

What the movie Uncut Gems tells us about debt, labor, risk, and what people are willing to do in order to win.

The moment the protagonist of Uncut Gems (Adam Sandler’s Howard Ratner) appears on screen, he is $100,000 in debt to some very dangerous people. We learn this when two goons sent by a loan shark named Arno (chillingly portrayed by Eric Bogosian) arrive at Howard’s shop in New York’s Diamond District. The goons assault Howard, take the watch and cash on his person, and continue to menace him until nearly the end of the film. The source of the original debt isn’t specifically revealed, but it’s strongly implied to come from gambling. Twin obsessions consume Howard—gambling and basketball—which he combines to a degree that places his and his family’s lives in danger. Nevertheless, Uncut Gems isn’t a film that’s solely about gambling addiction, or even bad choices, but a film about labor and profit.

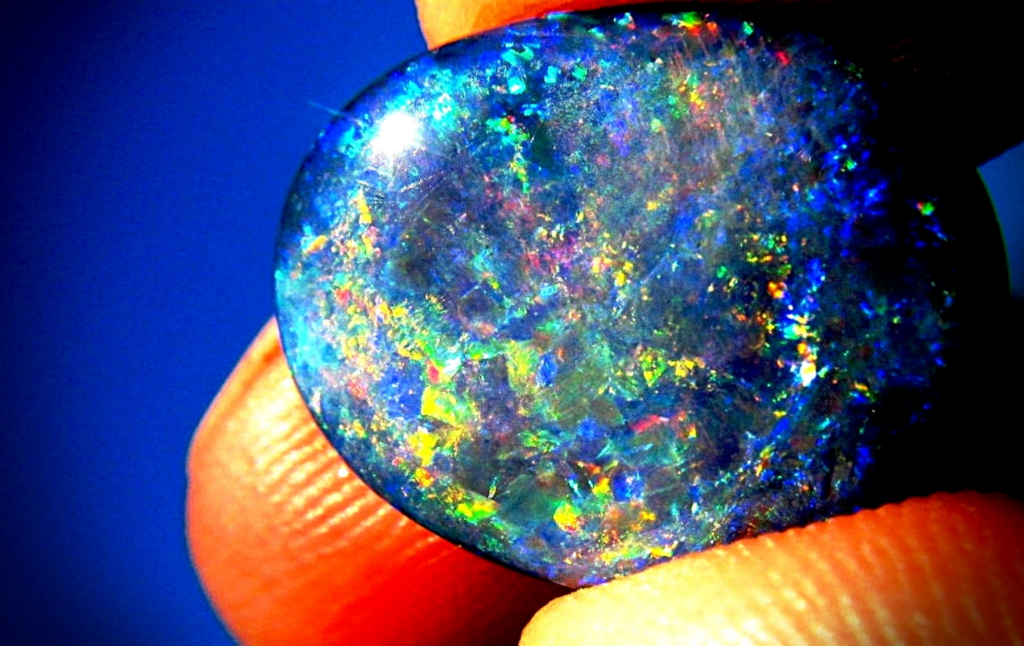

To this end, the film’s opening scene depicts Ethiopian miners belonging to Beta Israel—a black Jewish community—excavating rare black opals. In the process, one of their crew is seriously injured, a bloody shinbone protruding from his leg. A fracas erupts between workers and management; the overseers are Chinese, a nod to China’s large mining footprint in Africa and the global appetite for precious minerals. For his part, Howard Ratner (who is Jewish himself) is fascinated by the Ethiopian Jews—though not to the point of helping them—and purchases a black opal to sell at auction for what he hopes will be a huge markup, thereby settling his debts.

It’s tempting to view the opal as a MacGuffin, an otherwise useless object whose sole purpose is to drive the plot. But in Uncut Gems the black opal also functions as a cursed totem, one that bestows power or ruin on those who possess it. NBA star Kevin Garnett—playing a version of himself convincingly and not without subtle self-parody—comes to believe that the opal carries some sort of luck or magic that will give his Celtics an edge against the 76ers in the 2012 playoff series.

Yet in addition to being a potentially supernatural object, the black opal is also the literal embodiment of global capital. After being mined in unsafe working conditions by the aforementioned underpaid and exploited workers in Ethiopia, the opal is shipped to New York, where Howard plans to sell it for far more than what he paid. The auction house, of course, will take a cut. So will Gooey, a family member Howard prevails upon to gin up higher bids at auction. As it turns out, Howard ends up losing money at the initial sale when Gooey accidentally outbids Kevin Garnett. Following the later private resale of the gem to Garnett (whose own name evokes a precious stone, as Howard remarks), the NBA star, frustrated by the games and deception, asks Howard how much he actually paid for the opal. When KG discovers that Howard paid $100,000 for a gem he had been expecting to sell for upwards of $1 million, the following exchange occurs:

KG: You don’t see nothing wrong with that, Howard?

Howard: Ethiopian miners—you know what these fucking guys make? A 100 grand is 50 lifetimes for these fucking guys.

KG: A million dollars is more, is my point, you understand?

Howard: You want to win by one point or fucking 30 points, KG?

Here, neatly delineated, is the name of the game: maximum profit. Further explaining why he planned to overcharge for the opal, Howard says—in a line that has now become a ubiquitous meme—“This is how I win.” Sandler’s Howard loves to ball, loves to gamble, and, in a sense, he also loves to work. On more than one occasion, Howard chastises Julia (his employee and mistress played by Julia Fox in another of the film’s pitch-perfect casting decisions) for her sporadic work attendance at his jewelry store. Later, in the midst of a heated argument, he yells, “I just need to work.” Only after getting beaten and tossed in a fountain by debt collectors, showing up at his shop with a bloody nose, does he tell another employee, “I don’t want to work. Send everybody home.” Work, much as it is for K.G., is a game, and it’s only fun for Howard when he’s winning.

It’s not exactly a surprise that Howard thinks he’s doing exploited Ethiopian miners a favor by purchasing the opal. Though it’s difficult not to root for Howard much of the time, this is one of many instances in which he’s an asshole—a lovable, comical, abrasive, short-tempered asshole, but still an asshole. He claims a sense of kinship with the miners of Beta Israel, but he doesn’t care about their working conditions any more than his creditors care about his. However, as the film shows us, their situations are inextricably linked. At the conclusion of the opening scene depicting the mining accident, the camera enters the titular opal, showing the complexity of its glowing innards, then shifts to a screen in a doctor’s office depicting the view from Howard’s colonoscopy in progress. (This is funny because he’s an asshole, remember?) The transition is also illustrative in that it connects bodies on different continents caught up in two distinct vehicles of profit. To wit: The labor in a mine in a developing country, and the debt incurred by a worker in the developed world, are indirectly linked by the commodity of the totemic uncut gem.

Like the opal itself, Howard stands at the nexus of profit and exploitation, if not outright criminality. When he loans the opal to Kevin Garnett, he takes K.G.’s 2008 championship ring as collateral, pawns it, and places a series of bets on the NBA playoffs. Nearly all of Howard’s actions are an attempt to game the system, even to move outside of it. To quote Lewis H. Lapham: “The predatory mode of doing business depends upon the equation of something for nothing.” Yet how to define “the predatory mode,” exactly? “Something for nothing” is interesting in that it both perfectly describes the vulnerable debtor’s perception of a loan (money “out of thin air”) and the reality of the creditor’s position (eventual return of the loan amount plus much more). As it turns out, the predatory mode of doing business is closer to just “business,” and “something for nothing” finds its true expression in Marx’s explanation of interest-bearing capital, i.e., “money begets money.”

When Howard pawns K.G.’s championship ring, he receives a $21,000 loan at a 7 percent interest rate. This becomes a moot point when he leaves the ring in hock too long, rendering it the property of the pawnbroker. To get it back, he trades his beloved 1973 Knicks ring, and agrees to bump up the interest rate to 16 percent, which is high but not outlandish. To put this in perspective, according to creditcards.com, the average APR for new credit card offers during the week of January 15, 2020 was 17.30 percent. Surprisingly, there is no federal cap on credit card interest rates, which are also exempt from state “usury” laws. To take one example, on the heels of the Great Recession, a credit card issued by First Premier Bank featured a perfectly legal APR of 79.9 percent. In the 35 states that don’t cap them, interest rates on payday loans routinely exceed 600 percent. Last May, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders attempted to address this through the introduction of the Loan Shark Prevention Act, a bill that would cap the interest rate of all consumer loans at 15 percent. The legislation is currently unlikely to pass.

I’m not suggesting that Uncut Gems is a straightforward allegory about indebtedness (whether via credit card, student loan, or medical debt) in 21st century America. The film is far more ambitious and complex. However, the parallels are striking. During one threatening confrontation, a struggling Howard is restrained in the back seat of an SUV by Arno’s goons. Arno, radiating menace the way only Bogosian can, says, “I heard that Beni and Eddie are going to Timber Lake. And you know what else I heard? I heard you’ve resurfaced your fucking swimming pool! You know how that makes me feel?” Howard, while on the hook for $100,000, is sending his kids to camp (presumably an expensive one) in the Catskills, and resurfacing the family pool—what loan shark wouldn’t be irate? Yet these objections evoke a familiar kind of talking point, such as the one made by former Republican congressman Jason Chaffetz, that rather than shelling out money for a new iPhone, Americans should “invest it in their own health care.” Similarly, like Arno, our first impulse is to condemn Howard’s bad choices, poor self-control, and lack of financial responsibility. While it may or may not be justified to pass judgment on Howard (the movie itself, wisely, doesn’t pass judgment, and refuses to specify if Howard’s gambling problem is truly something he can’t help), Americans often have no problem when the wealthy spend their money frivolously—in fact, we celebrate them. The tension reflected in Howard’s situation arises from his status as rich but not “rich enough.” Though he owns a small business, he works alongside his employees, and his drive to accumulate extreme wealth is aspirational. His troubles with debt, though potentially self-imposed, nevertheless mirror the plight of millions who struggle through no fault of their own.

Here’s Howard, bloody and weeping in his office: “I can’t figure out what I’m supposed to do. Everything I do is not going right.” Total outstanding debt in the United States as of November 2019 was over $4 trillion. Much of that is due to our broken health care system: Taking on crushing medical debt is hardly a choice, and it’s an absurdity that the United States spends more than twice the OECD average per capita on health care. Other forms of debt such as auto loans or mortgages are considered relatively uncontroversial, but credit card debt is particularly insidious for the predatory interest rates mentioned above, and because it links a loan to the habit-forming method of payment itself. Credit card debt alone amounts to $1 trillion of the total American debt crisis, eclipsed by student loan debt at $1.6 trillion.

The latter has ballooned along with rising tuition costs because borrowers know that a college education results in an annual earnings boost—about $17,500, according to Pew Research Center. Introduced last June by Bernie Sanders, the College for All Act of 2019 would eliminate all outstanding student debt and make public universities, community colleges, and trade schools tuition-free, paid for via a tax on Wall Street transactions (Elizabeth Warren has proposed canceling up to $50,000 of debt for every borrower making under $100,000).

A number of countries around the world provide college education tuition-free with low or nonexistent fees, including Finland, Germany, and Slovenia. The United States itself has a long history of providing free or affordable college in limited contexts, such as the University of California, the University of Florida, and the City University of New York systems, all of which began charging in the 1970s. Americans rightly see an undergraduate degree as a necessary credential to succeed, and have borrowed a collective $1.6 trillion to improve their job prospects. There is no reason college should be unattainable without massive amounts of debt. There is no reason people should have to take on massive amounts of credit card debt in order to pay for basic necessities and comforts. For the moment, however, and for far too many, debt is how you win.