The Data Show That Socialism Works

People are better off to the extent that they live under democratic socialism.

The left, right, and center disagree on the merits of socialism. But these disagreements are often impenetrable, as they rarely even agree which countries are socialist. Socialist-skeptics point to Venezuela as an example of socialism run amok, while socialists point to the Nordics as evidence of its virtues. To counter the obvious success of the Nordics, some will define them as actually capitalist. The capitalism-or-socialism binary gets further complicated as debaters introduce terms like “welfare state capitalism,” “social democracy,” “democratic socialism,” “state capitalism,” “state socialism,” and more. This debate doesn’t get any clearer among self-identified socialists, as many have their own pet definitions. With such barriers in the discourse, how can we possibly measure how people experience socialism?

Instead of cramming countries into a discrete buckets of “socialism” or “capitalism,” it’s better to view countries as bundles of institutions. Those institutions can operate along a socialist-capitalist spectrum, and exist with other institutions that fall elsewhere. This approach forces us to consider which institutions are most relevant and how they can best be measured to capture the differences between socialism and capitalism. Once we have a pliable measurement, we can then see whether people in socialist societies can be happy — or destined to a life of misery.

- Controlling and Owning the Means of Production

The clearest divide between capitalism and socialism is over the “means of production” and who controls and owns it. Defenders of capitalism believe the means of production should be in the hands of private actors — even if they are just a cabal. Socialists, though, believe the means and fruits of production belong to all. So which institutions equally share control and ownership of society’s resources and processes?

- Ownership

The most straightforward measurement is direct ownership of firms. States of all types can and do run “state-owned enterprises,” with full control over the firm’s operations, while receiving all of its profits. States can also have partial ownership and control, or just run a diverse portfolio of financial instruments in sovereign wealth funds. These institutional forms combine, in addition to public debt, to create public wealth. The amount of public wealth relative to private wealth in a society is thus one good proxy for its degree of socialism.

- Public Goods and Welfare

Private firms and individuals don’t just produce stuff and get financial returns. They also sell those goods and services to customers, and give wages and income to workers. States bypass this role of private actors by directly giving income, goods, and services to its citizens: roads, education, health care, retirement income, unemployment income, public employment income, etc. To fund this (or in MMT terms, to offset inflationary pressures), the government requires taxes from private corporations and individuals.

There isn’t a conceptual bright line between state ownership of firms and funds, and government departments and budgets, but firms and funds tend to operate more in markets, whereas government departments and budgets do more non-market activities.

- Democracy

So far, I’ve focused on the relationship between private actors and the state. But a big state role in the economy is no guarantee that society’s resources will be equitably shared or its processes will accurately reflect the will of the people — for that, what’s needed is a strong democracy. This reasoning is why so many socialists are prefixing it with “democratic.” Democracy is a key element of the socialist project, and differentiates it from the institutional character of states like Venezuela, China, and the former Soviet Union. These countries undeniably feature strong roles of the government in the economy, but because they lack democratic legitimacy, they do not serve the will of society.

- Labor Unions

The final institutions that determine the degree of socialism are the organization of workers. Of any distinct group in society, the working class is the largest and has the closest and most tangible ties to the means of production. Thus, when properly organized, they have the power to force either private or state owners of the means of production to respect their democratic rights at the worksite or in society at large, and to more equitably share the gains of production.

What does “properly organized” look like? Independent trade unions (that is, they can’t be absorbed by the company or the government), sector wide bargaining regimes, worker co-ops, and worker representation on the board (co-determination). Organized workers is another area where Venezuela, China, and the former USSR fall short and limit their degree of socialism.

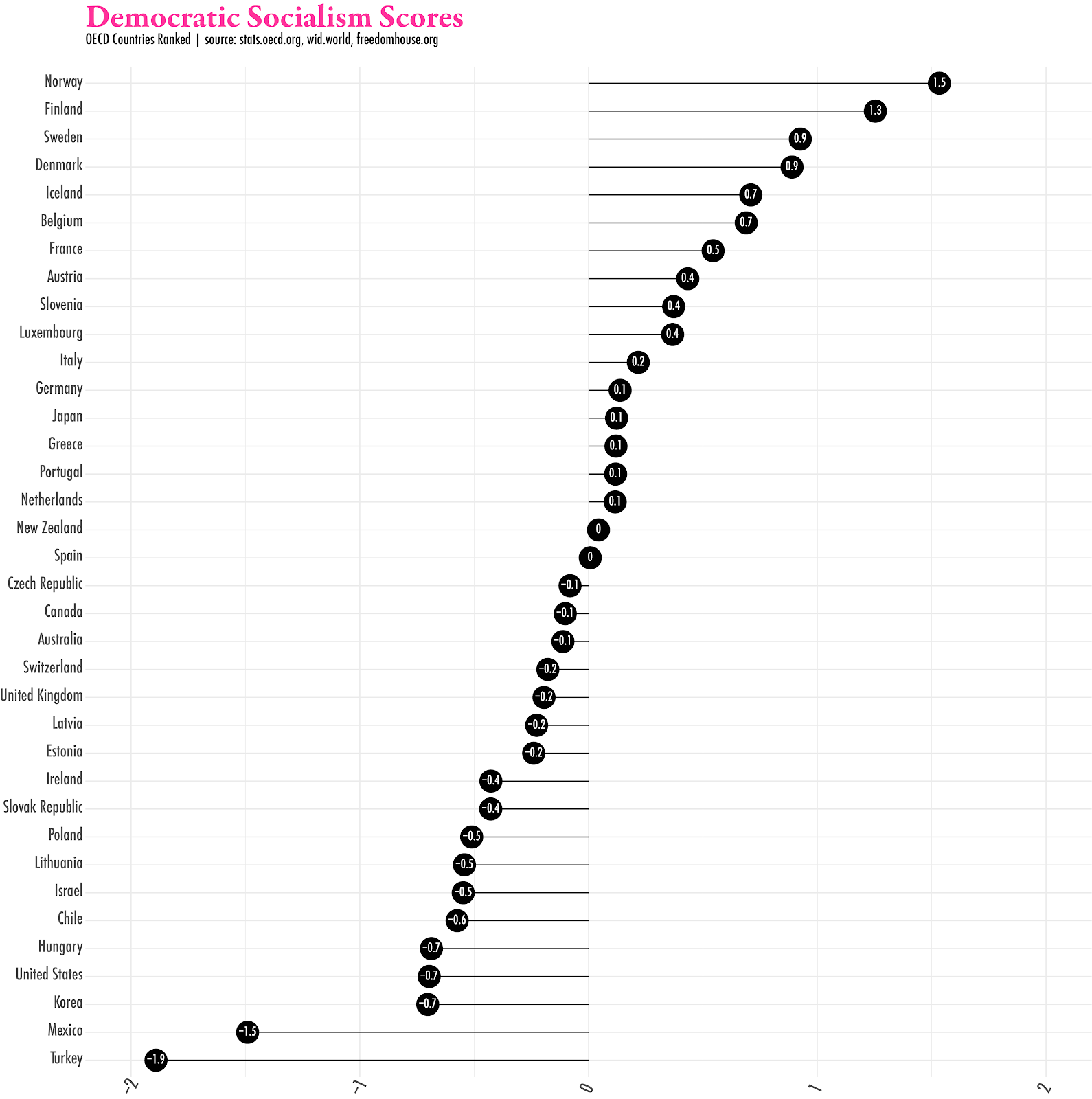

Democratic Socialism Score

With that four-part institutional breakdown as my guide, and inspired by Nathanial Lewis’s “scale of socialism,” I used data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Inequality Database, and Freedom House to build a “Democratic Socialism Score” for a variety of countries. Due to the limits of their databases, I could only score 36 countries. I would love to apply this score to all countries, but the data limits can’t be avoided.

The score derives from four components, with each made up of several subcomponents. The “State Ownership Score” combines data on the market value of State-Owned Enterprises relative to the overall economy, the share of government financial assets as a percentage of GDP, and the share of total public wealth as a share of total overall wealth. The “Public Goods and Welfare Score” combines government expenditures on welfare transfers, education, housing, etc. as a share of GDP. The “Democracy Score” simply comes from Freedom House’s “Freedom Ratings.” And the “Union Score” combines the percent of the workforce who are members of unions and the percent who are covered by collectively bargained contracts. To appropriately average these scores into a single overall score, I converted them into “standardized t-scores.”

Now that we have a way to approximate the degree of socialism in countries, we can see how socialism correlates with important indicators of the population’s quality of life. By looking at actual life outcomes across countries, we can see whether it’s justified to argue that socialism is incompatible with living the good life. If we find that more socialist countries are more productive or healthier than capitalist ones, that’s not proof that socialism causes such outcomes—but it does offer a hint. And more importantly, if we find correlations that move in the opposite direction of what a capitalism-booster would argue, it’s powerful evidence against the idea that capitalism has unique features that lead to prosperity.

Making Money

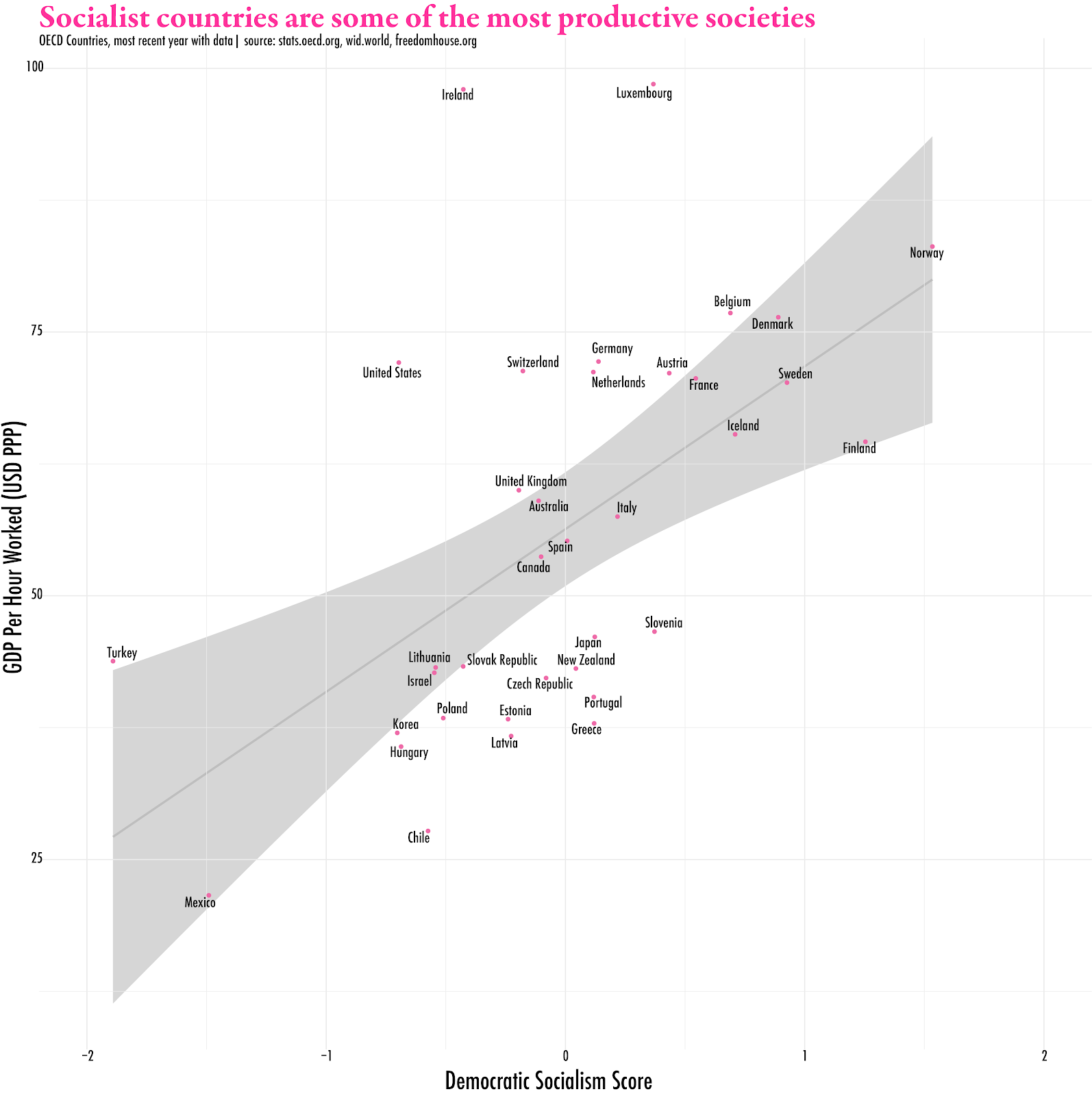

Socialist-skeptics usually argue that socialist societies cannot keep pace with capitalism’s capacity to efficiently produce goods and services. Does this claim hold up?

The claim does not hold up. While there is a lot of variance around the trendline (r^2=0.29), the trend goes in the opposite direction of what the skeptics would argue. Our No. 1 Democratic Socialist country, Norway, has the third highest productivity per hour behind only the two tax-haven countries (Ireland and Luxembourg). Other socialist-leaning countries like Denmark, Sweden, and Finland score high as well. So it’s fair to say that socialism does not hinder productivity — if anything, it helps.

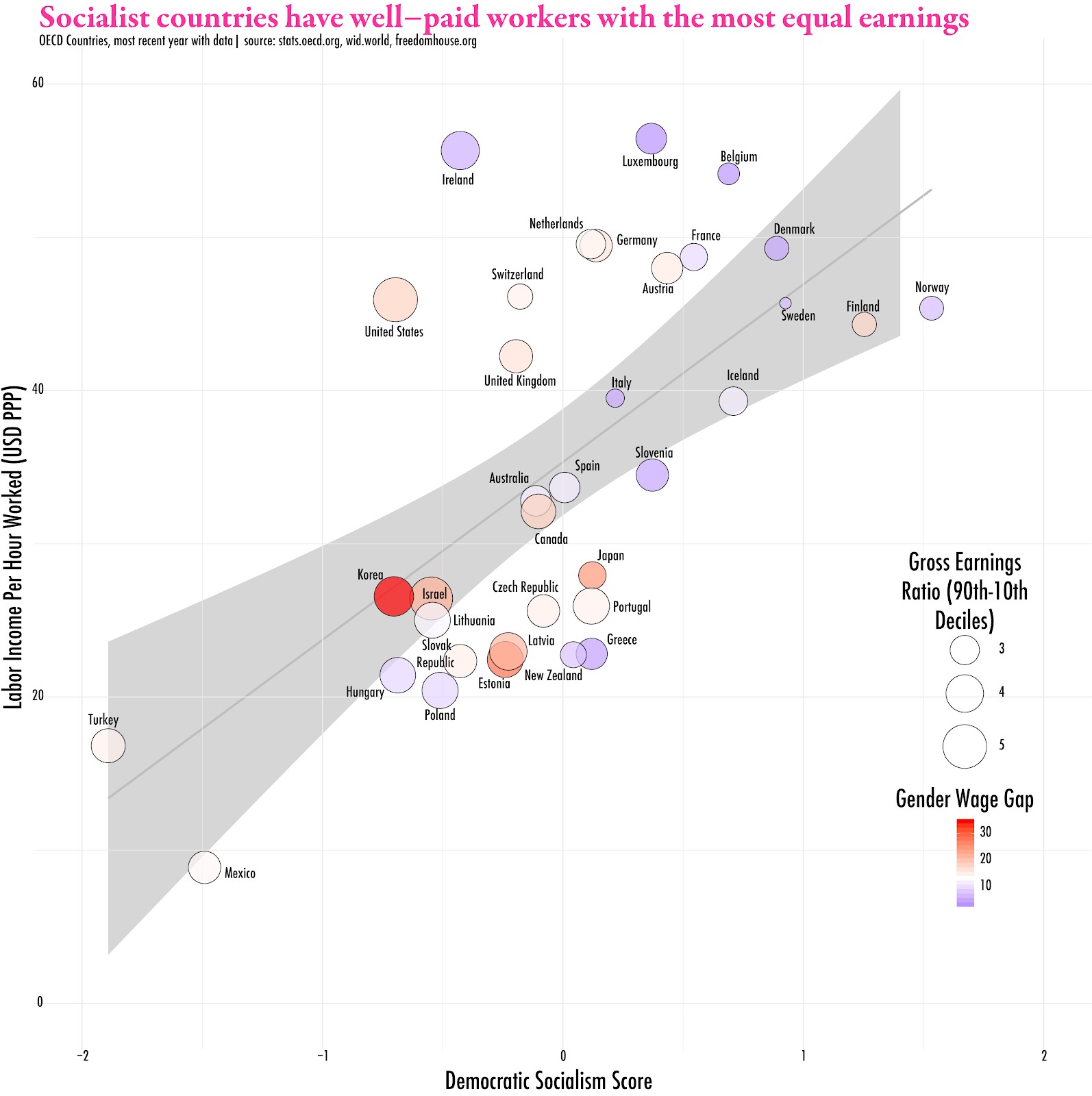

Raw productivity is important, but how that productivity is distributed matters for people’s actual experience. Since most people earn a living by working, the share of national income going to the labor force matters, as does its distribution within the labor force.

Here we find that workers in most socialist countries earn high incomes per hour worked — comparable to the United States. But we also find that equality among workers is much higher in the more socialist countries. In such countries, earnings are compressed between the top and the bottom, and between genders.

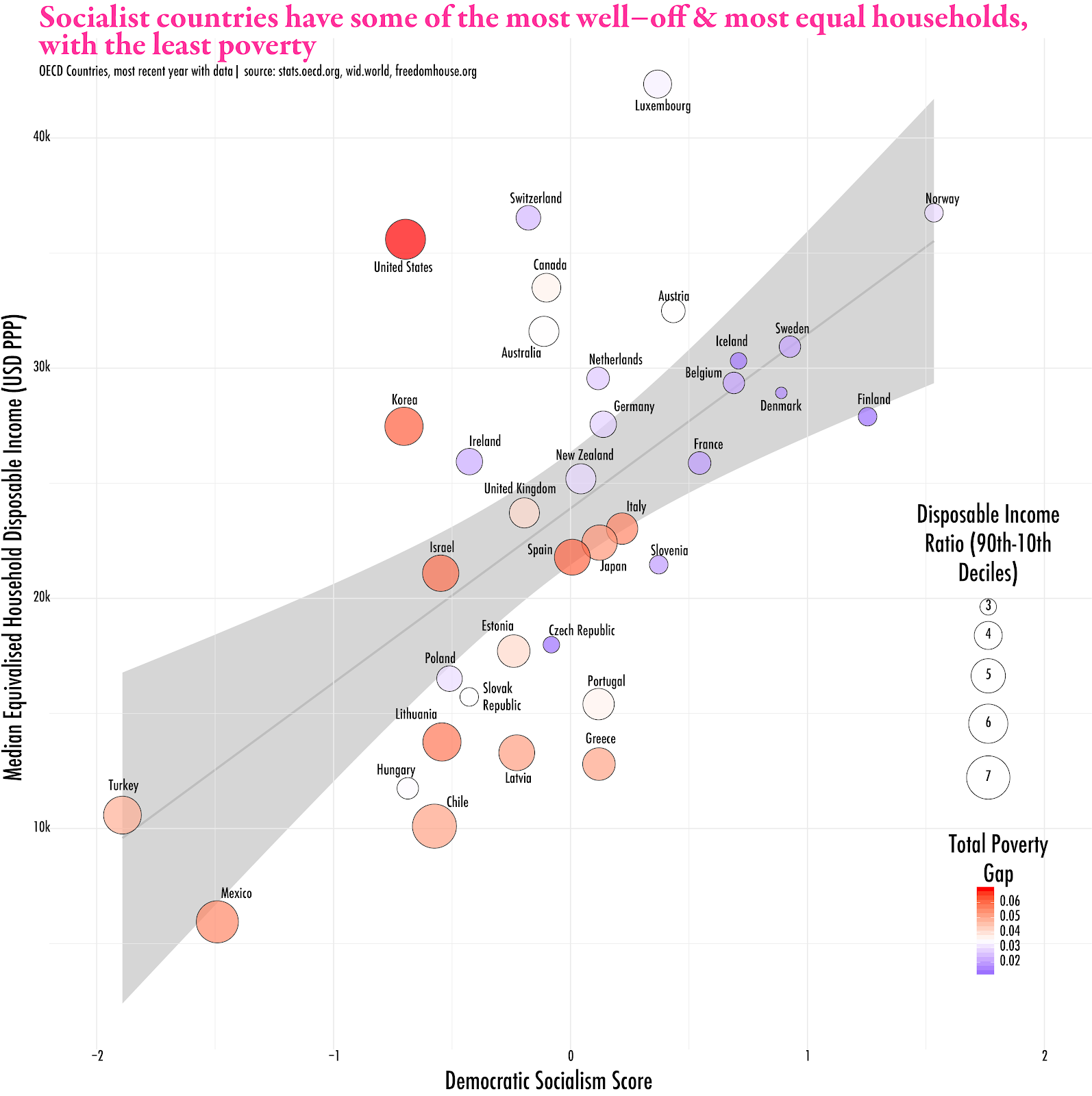

While the working class is large and important, non-workers are almost as large. And all workers are at some point unable or unwilling to work, and non-workers depend on workers’ income. That dependence can be a parent caring for a child or an aging relative, or payroll taxes funding insurance for unemployment or disability. So instead of focusing on the earnings of workers, let’s expand to look at household disposable income. That is, income after taxes and transfers from workers, owners, and non-workers.

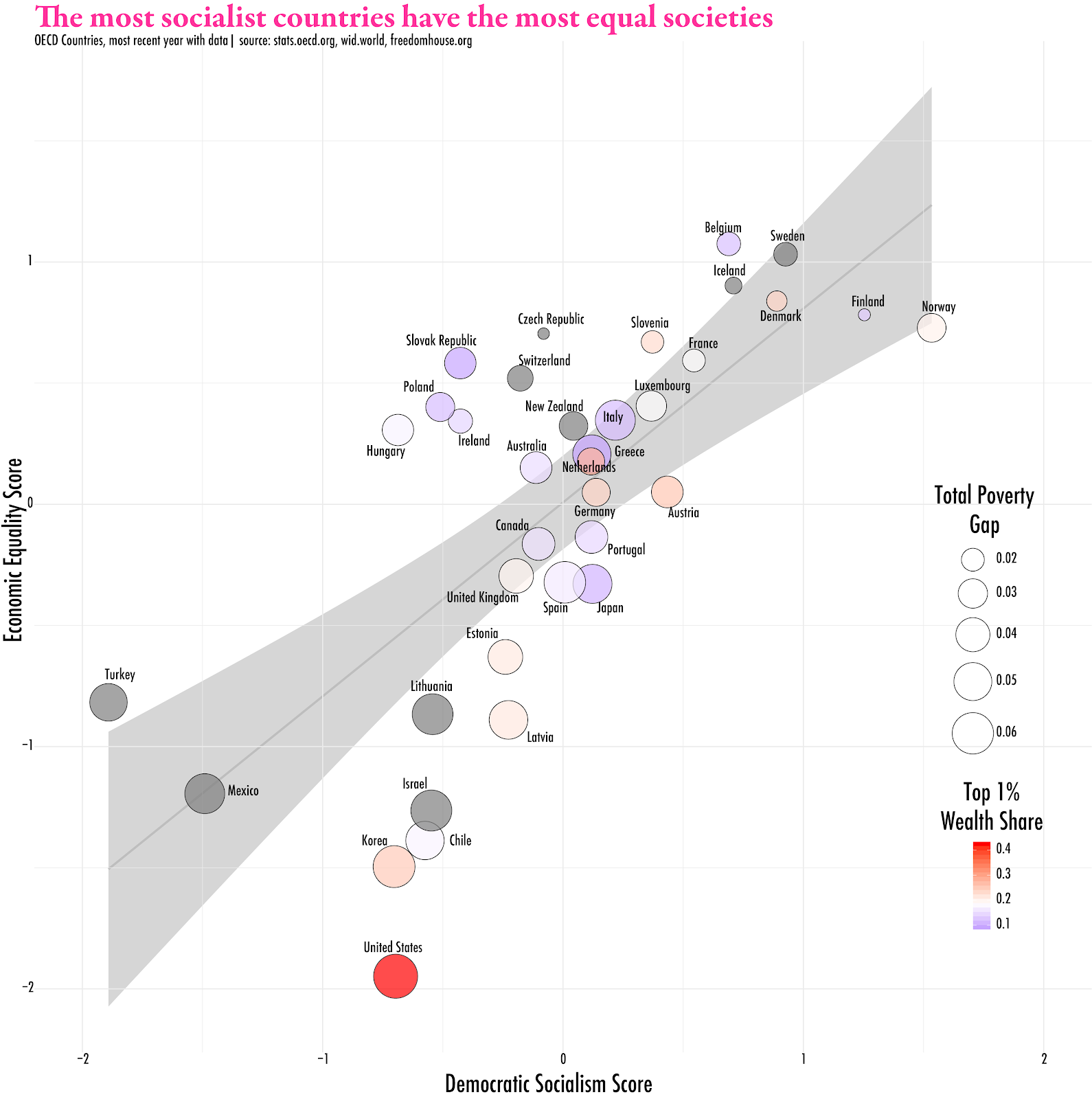

A similar trend emerges. Typical households in more socialist countries have high disposable incomes, while also compressing the differences between top and bottom households, with some of the lowest poverty gaps on record. Socialist countries being more equal is not surprising, but the point is emphasized in the following graph:

The five countries with the five highest socialism scores also have the five highest economic equality scores. The economic equality score derives from an average (using standardized scores) of earnings ratios between the 90th and 10th deciles, the gender wage gap, the total poverty gap, post-tax-and-transfer gini coefficients, disposable income ratios between the 90th and 10th deciles, and the share of wealth from the top 1 percent.

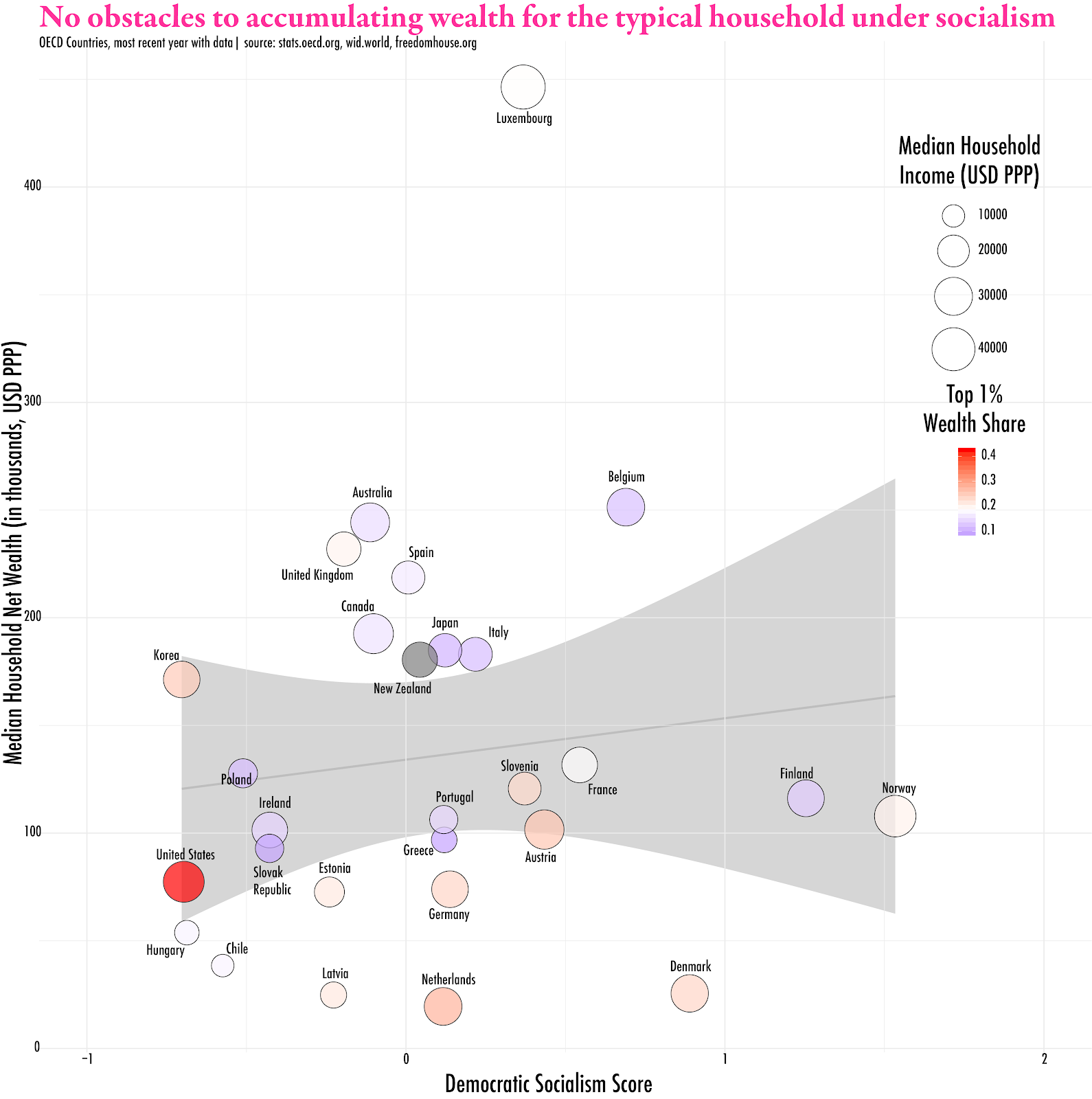

While flows of income are important, the ability for people to save and earn wealth also matters. Do socialist societies limit this ability?

Wealth data across countries is harder to get, but the data we have does not support the idea that socialism impedes accumulating wealth for the typical household. The median household in Norway, Finland, and Belgium all have more net-wealth than the United States.

Being Relaxed and with Family

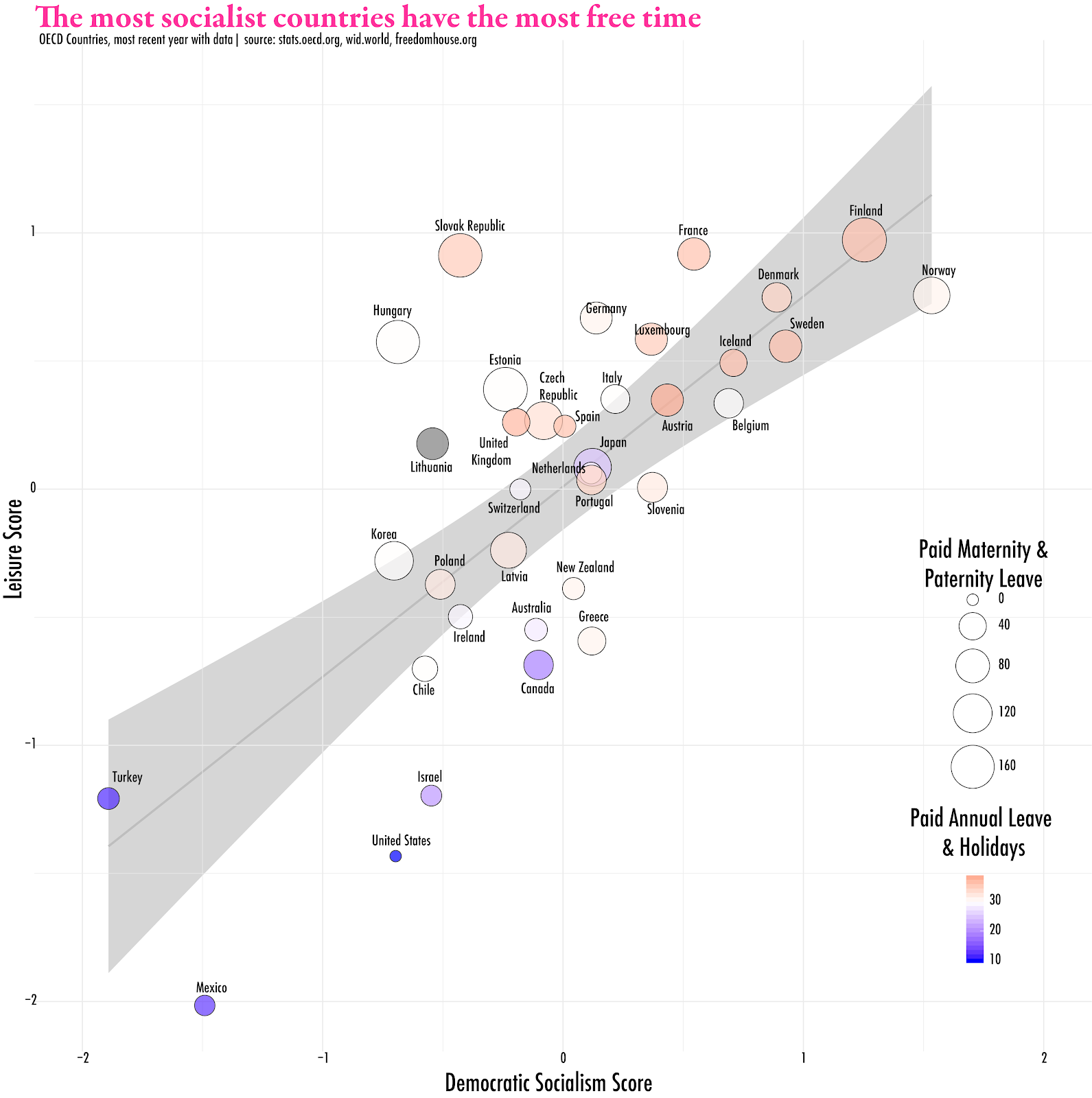

Our purpose isn’t just to work and earn money, but to enjoy our limited time being alive. The 19th-century labor movement put it this way: “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, and eight hours for what you will.”

More socialist countries also enjoy a lot of paid time off. This comes in the form of paid annual leave, public holidays, and paid maternity and paternity leave. The “Leisure Scores” averages (using standardized scores) these forms of paid time off, along with hours worked per worker, and self-reported “leisure and self-care” time.

Being Healthy

In addition to earning money and time off, our ability to enjoy any of it depends on our health and the health of those we love. To measure the health in society, I created another encompassing measurement, derived from life expectancy, maternal mortality rates, neonatal mortality rates, and infant mortality rates.

Socialist countries are also healthy. They have long life expectancies, with low maternal, neonatal, and infant mortality rates. These metrics combine into the overall “Health Score.” Note that three of the most non-socialist countries — Turkey, Mexico, and the U.S., have the worst health scores among OECD countries. In the case of Turkey and Mexico, low overall wealth might explain the poor health, but what about America?

Being Satisfied

Pulling all these factors together, let’s look at how the degree of socialism in a society correlates with self-reported “life satisfaction,” along with some other objective measures of their material reality.

Based on what we’ve seen so far, it shouldn’t be surprising that the most socialist countries also report some of the highest scores for overall life satisfaction. The typical worker and household have high incomes and wealth, while living in healthy, equal societies with plenty of time off. Meanwhile, people in the least socialist countries don’t have as much money, are overworked, live in stratified societies, and are more likely to be surrounded by illness and death.

Is Socialism Stealing Innovation?

Sure, most workers and households get as much money, if not more, in countries with socialist societies as they do under capitalism. And sure, socialist societies appear to be more healthy, happy, and equal, while having more free time and fewer preventable deaths. But maybe it’s because they are somehow free-riding on the backs of innovations that are due to the magic of capitalism.

Nope. Capitalism does not have a special ability to innovate. While the most socialist country (Norway) ranks less than the U.S., the U.S. ranks below Sweden and is comparable to Finland. Overall, the trend is fairly weak, with even more variation than previous trend lines. And “innovation output” is a more murky concept to measure than money, health, equality, and leisure. But this data does not support the idea that socialist countries rely on innovation from capitalism.

Conclusion: Bread and Roses

Socialists believe that society’s means of production should serve everyone. To get there, socialists advocate for state-owned firms and funds, public goods and universal welfare programs, democracy in government and at the worksite, and labor unions and other forms of worker power. Capitalists and their ideological allies argue all these institutions impede the freedom of owners of private property — who are the true engines of prosperity. Through their investments and ingenuity, capitalists produce so much wealth that even when they hoard most of it, everyone else is ultimately richer, healthier, and happier. Societies that get in the way of capitalists, even for noble purposes, are doomed to fail and be miserable. And yet, when we look at the countries that have most impeded the freedom of capitalists, we find the opposite: People living under socialism are the ones most likely to be living the good life.