I watched a boy die today.

I watched him wander his concrete cage in a stupor while the walls swallowed him whole. I watched him collapse on the hard floor, clutching his heart as it exploded—like a star. I watched him writhe and gasp while the fever cooked his brain. I watched him thrash his legs the way you thrash your legs when the pain is just too much and has nowhere else to go. I watched him go limp, alone, when the light finally left him.

I watched. I cried, watching, begging, pleading to anybody to please let somebody come and help him—but nobody did. And I knew they wouldn’t. I already knew that the boy, Goyito, had died seven months ago.

His full name was Carlos Gregorio Hernández Vásquez. People called him Goyito. He was brown, like me. He was one of eight children. They are a big family, like my family, and Goyito wanted to help provide for them, help care for them, help pay for his special-needs brother’s medical bills.

Their family is smaller now.

With his older sister, Goyito left his home village (San Jose del Rodeo) in Central Guatemala and hit the long road north. They were coming here—the coyotes brought them. And they made it. Despite the distance, the gangs, the police, the extortion, the buses, the rafts, and the heat, they actually made it. They crossed.

And Border Patrol immediately captured them, and separated them, as is the Law.

Days later, Goyito died of the flu, scared and alone, in a cell that you and I helped pay for.

He was 16 years old. For 16 years, he lived. He loved and he tried, he grew and he felt, he learned and dreamed and got into trouble. He helped and failed and played and thought about other people. He watched the rain and burned his tongue. He got too big for his clothes. He pondered the future and breathed in the orange sun as it fell. He touched the world. He lived.

He came from the earth, as we all do. His parents, Bartolomé and Gilberta, poured their earth into each other, and they made him. They made him. Do you understand? They shepherded him, lovingly, from themselves out into the blistering world. He was human, he was real—his skin and hair and feet and eyes, his smile, his cries, his teeth and voice. He was their boy, their blood and earth and light. They made him, and he lived.

He was somebody’s baby. And he died. He died on the cold ground in the custody of a country that looked at him—all his life experiences, all his memories and dreams and humanity—and saw nothing but a worthless, brown cockroach.

His loved ones watched him die, months and months after they had already lost him, when the footage was finally made public. They watched, unable to hold him, unable to comfort him in his last confused and scared moments. They watched, knowing that merely yards away, just down the hall, a good number of healthy and able-bodied Americans sat, bored, whiling away the night. They sat, bored, breathing effortlessly, unthinkingly, while somebody’s baby kicked and coughed and clung desperately to being alive, fighting and failing to hold back a universe of needless pain as it slowly crushed him into unbeing.

The Border Patrol’s “subject activity log” claims that an agent checked on Goyito three times over the course of the night, from the time he collapsed to the time he was found dead in the same spot, a bloodpool cradling his head. The surveillance tape, which CBP tried to keep from the public, can neither confirm nor deny that, because the tape, abruptly, mysteriously, goes black for those four hours.

I imagine, in those final moments, Goyito wished he could just go home.

I imagine all those times when I was a kid, when I was sick and frightened, when I called out to my protectors—and they came, and I was ok. Imagine your protectors. Imagine calling to them, needing them, and hearing nothing but the buzz of your jail cell light as the years before you slip away into darkness.

Imagine your soul squealing like a panicked mouse, begging not to die—and no one coming.

I can never forgive this country.

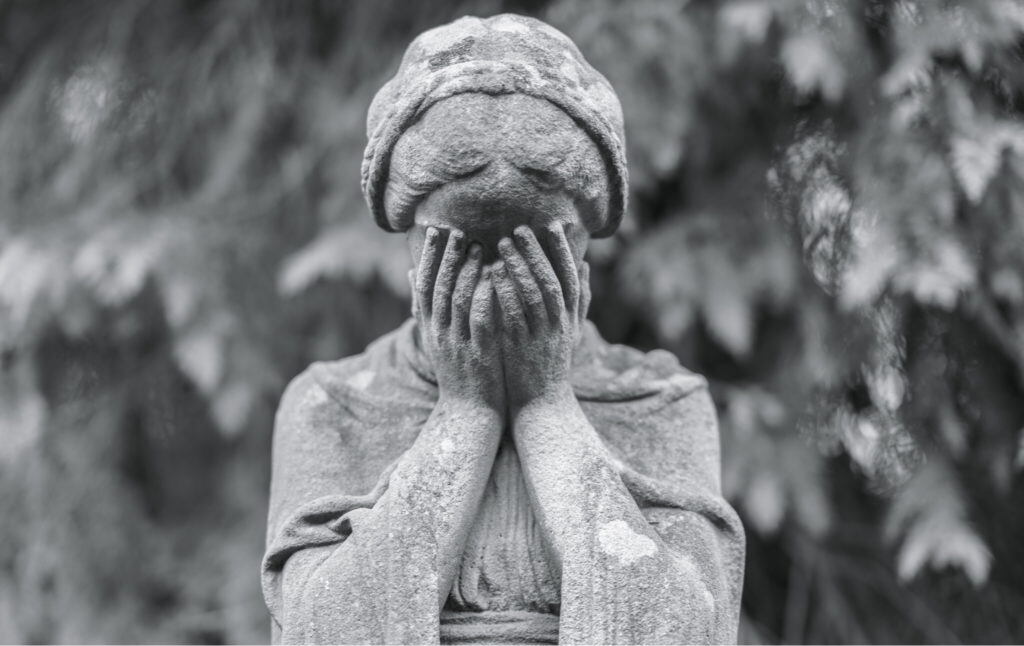

I think we don’t know what it is to be human. Because, if we did, it would probably crush us. And I think we know that.

Ours is a culture, after all, that is all but defined by a people’s desperate will to forget their own shared humanity. Because we have to. Because, in this country, we have not equipped ourselves to confront the pain of the crimes we committed to get here, and the crimes we commit, still, to stay— and to forget. Because we cannot reckon with what we have done to each other, and what has been done to us, in turn. Because we live so routinely amid so much inhumane cruelty, because we toil so listlessly in the ruthless monotony of a world that treats us—and teaches us to treat others—like disposable things. Because it hurts enough to live like this, and to convince ourselves that this is all being human can be. To be reminded, however fleetingly, that it doesn’t have to be this way, that we were made for more than this—that we deserve more than this, that it could be different, but isn’t—is more hurt than most of us can handle.

I have to believe this is how many people feel. I have to. I have to believe that so many of us submit so willingly to The Way Things Are, not because we are heartless things, utterly callous to the pain of others, but because we know that we could not bear to gaze into the inhumanity we have wrought and know beforehand that we will only be able to feel broken before it, and individually powerless to do anything about it. We’re only human, after all. Our hearts can only take so much.

But our hearts, too, are capable of incredible things. Together, we are capable of feeling, and being, and building everything this system has taken from us. And it has taken from us. It has taken so damn much from us.

This stupid, brutal world has denied us our god-given right to be as human as we can be—as human as we are supposed to be. And if it has made us too thing-like to mourn Goyito, scrolling past him to the next tragedy, we should mourn that, at least. We should mourn our lost ability to mourn him as our own, which is what he deserves.

We should mourn the humanity that has been stolen from us. And we should rage against the pitiful synthetics we’ve been forced to accept in its place, and against all the ways our most human yearnings—for safety and belonging, for happiness and purpose—have been co-opted and sold back to us at the cost of so much human misery.

Be honest. What authentic human feeling has this system not sullied and cheapened for us? What material comfort—like food and toys and clothes—does it afford without requiring us to break ourselves or others to get it? What basic human needs—like shelter and medicine and the ability to provide for our families—does it not insist we can only have by denying the same basic needs to others in different, browner skins?

What joy—true, genuine joy—does such a system provide that does not come with the pricetag of boundless human suffering? A suffering wrought upon others solely to make our half-joyed lives more bearable? What possibilities has it stolen from us to feel joys that we were meant to feel but are not even able to currently imagine in this vile, sugar-coated hellscape?

What value can life possibly have in America when we are forced to accept that it can be extinguished so gleefully, taken so needlessly, and forgotten so swiftly? And when life is lost, what genuine empathy does this culture allow us to feel that isn’t immediately suffocated by a compulsory hopelessness that things could ever get better?

What type of world could we have—what type of people could we be—if we were allowed to feel enough to feel this pain of others, and to collectively live in a way that tried harder to avoid it? We could find out. We could do better than this.

We have to do better than this.

Editor’s note: Goyito’s family has requested that people not watch or share the video of his death, so we have removed any links to it.