Five Self-Written Reviews of “Why You Should Be A Socialist”

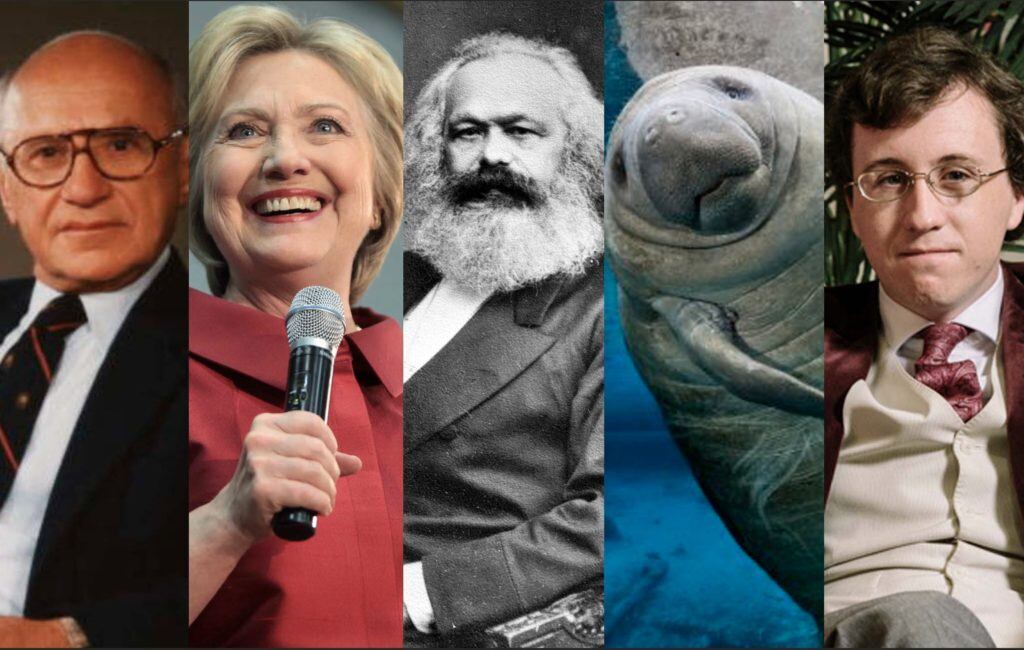

Takes by a Libertarian, a Liberal, a Marxist, a Manatee, and Me.

My first book with a major publisher, Why You Should Be A Socialist, comes out today. My personal opinion is that it is worth buying and reading. (If, however, you would prefer to read the book for free, you may try the “socialist” alternative by visiting your public library.) I’ve written this book in order to explain my personal understanding of socialism, to show why I think its principles are just and wise, and to defend it against the many absurd charges made in books like Senator Rand Paul’s The Case Against Socialism.

You can tell from the title of Why You Should Be A Socialist that the book is intended for people who are not socialists already. I did not call it Why You Are A Socialist. That title would have sounded ridiculous, though I think it’s very easy to slip into a kind of left writing that is somewhat like that, talking to existing converts rather than skeptics. I myself am an “evangelical” socialist, meaning that I want to bring the good news to those who haven’t heard it. I want to take people who are not convinced and respond to their objections. I want to guide them slowly and meticulously. I want to treat counterarguments seriously and show why critics of socialism are all wrong. (Part III of the book is actually titled “Why Critics of Socialism Are All Wrong.”) I want to be thorough and cautious, and rigorously document my factual assertions. (Come for the main event, stick around for the 50 pages of endnotes.) I intended to write a book that socialists could give to those who ask them “Hey, what’s this socialism thing all about?” (And also could give to right-wing relatives as a prank Christmas gift for an amusing reaction.)

The book is also for socialists, though, because I think there is value in us talking about our beliefs together. As I talk to DSA members around the country, I ask them a lot what they mean by the word socialism, and their answers are all very different. I do not actually take that as a sign that socialism is meaningless, or that—as uncharitable right-wing critics would conclude—they “do not actually understand” socialism. Rather, I see it as a sign that people share a common set of instincts and aspirations but are still working out how to talk about them. There are very obvious core commitments: egalitarianism, antiracism, feminism, economic democracy and the hatred of the ruling class. But the precise meaning of socialism has been hotly debated among socialists for as long as the term has existed, and the question has even torn socialist movements and groups completely apart.

Why You Should Be A Socialist does not, and could not, ever propose an answer to the question “What Is Socialism?”, and one thing I argue is that it’s actually not worth dwelling on too much. I think it’s a bit like trying to find a definitive and satisfying answer to the question of what “justice” or “democracy” or “love” is. But I do think that, like those other words, it is useful, and captures some common instincts, principles, and aspirations. I think the value of the book for socialists is that it offers a clarifying discussion of what it is we think and why we think it. You might assume that would be obvious: Don’t people already know what they think? But sometimes our thoughts are kind of an amorphous blob, and we feel somewhat inarticulate when we’re asked to actually explain them. My aim for the book, then, is to kind of organize socialist thinking a bit: Where do we begin? What are our core ideas? What are their implications? What kinds of actions should we take?

I am sure there will be intense disagreement with me about my answers to these questions, even from people who consider themselves sympathetic to my politics. My hope is actually that for socialists, the book will be a useful starting place for fruitful debate. You might agree with some bits of it and not others, you might feel that in some parts it goes too far and in other parts not far enough. It offers my own personal understanding, and my hope is that at the very least this will prove provocative and stimulating. I hope you enjoy the book. I really do think it’s worth reading, no matter who you are and whether or not you are a socialist.

In looking over the book, I’ve been thinking recently about how people will likely react to it. I have decided to write some reviews in the voices of different people (and one non-human animal) of differing political tendencies. I wrote these reviews because (1) it’s useful to get into the heads of others who are quite different as it helps them understand both their world views and your own (2) by writing these negative reviews myself hopefully I make it slightly less likely that individuals like these will write negative reviews, because what could they even add? (3) it gives me a chance to respond to what some commentators will likely say and (4) I find it pleasurable to impersonate manatees. I have also never seen a writer write negative reviews of their own book before, so I thought this would be “unique.”

The Libertarian’s Review

Basic economics is not hard to grasp, but for some reason a century of bloody experimentation with socialism has not been enough to convince the left of the fundamentals. Free markets succeed, unfree markets do not. Is this really so difficult? Leave people alone, let them pursue their own interests as they see fit, and you get prosperity and growth. Have the state begin social engineering projects and you get murderous tyranny. We have run the experiment dozens of times and the results are always the same: Capitalism gives people what they want, socialism gives them what the planners want. For a book called Why You Should Be A Socialist to come out in 2019 shows the continuing human intoxication with the illusory promise of “free” stuff and the failure to grasp the central lesson of economics: There are no free lunches. Most people discover this as children, but some, such as Nathan J. Robinson, manage to remain ignorant of it into adulthood.

Where to start with this book? The classic erroneous conflation of capitalism with greed? The failure to reckon with the catastrophic history of his political creed? The lack of answers for simple questions about how a socialist society will operate? Robinson does not seem even to understand where his clothes and his food come from. A chapter of the book is stingingly critical of Amazon, which he calls “neo-feudal,” despite Amazon being the most trusted brand in the country—more than the U.S. government and the press. Here we see the undemocratic underbelly of “democratic” socialism: Robinson speaks movingly of the “people” and their wishes, but ignores survey results about what those wishes actually are. The market is the true vox populi. It speaks, and it says: in Amazon we trust, in government we do not. How farcical, then, for Robinson to portray Jeff Bezos—who has revolutionized the process of giving people what they want, by putting customers first—as some kind of villain. Truly we are in topsy-turvy land, where efficiently satisfying human wants becomes despotism and telling people what they ought to want is democracy.

Robinson fills Why You Should Be A Socialist with anecdotes about the misdeeds of American corporations, illogically treating the exception as the rule. He sees free market policies as “indifferent” to people’s suffering, when the opposite is true: We demand free markets because we have seen the tremendous reduction in global human suffering unleashed by capitalism, and we want more of it. Robinson insists, as he has to, that he is not advocating a return to “Soviet-style” socialism. But what, then, does his socialism consist of? Of good feelings? Of the mad utopian imaginings he fills a chapter with? This book shows only that socialism is a kind of mental illness that afflicts comfortable Western intellectuals. They become intoxicated with visions, totally divorced from reality, and they cannot see the facts that are in front of their eyes. They nourish a pathological hatred of an economic system that has given them everything, and they wish for the destruction of the source of human prosperity. They see mutually beneficial free exchanges as coercion, and state coercion as democracy. Socialism is as twisted and dangerous a vision today as it was in 1917, and let us hope that the millennials infatuated with this terrifying and ignorant creed soon wake up and notice the blessings they have been given by capitalism.

The Liberal’s Review

We live in extreme times. An orange tyrant in the White House, environmentalists marching in the streets: The populace is exploding with rage, entranced by visions of a mythical nationalist past or an equally mythical utopian tomorrow. There is corruption and nepotism at the highest levels of government and our largest corporations have forgotten the lofty sense of loyalty to community that once guided their operations. For those of us who believe fundamentally in American institutions, and fear their erosion by radical populists of both right and left, it is distressing to see that the post-Cold War faith in sound liberal governance is breaking down. It seems that reason has taken a holiday, that rationality and civility have fallen by the wayside. It is not surprising, then, that we see books like Why You Should Be A Socialist popping up.

The good news is that much of what is advocated in this book is what liberals have long been advocating. Antiracism? Check. Feminism? Check. Measures to mitigate suffering? Check. Principles are being claimed for socialism that are fundamental to the liberal egalitarian notion of “equal opportunity.” Can anyone disagree with Robinson when he speaks of the importance of a good society where all are well-treated? When he movingly pleads for sympathy with the poor and benighted, one is tempted to take out one’s checkbook and support the nearest charity. But Robinson refuses to give credit where it is due: He states the fundamental principles of liberal governance as his own, and then has the audacity to crudely title his critique of liberalism “Polishing Turds.” Well I never!

Like many of history’s hot-headed and youthful, Robinson is ablaze with fury at injustice. And just like the revolutionaries of eras past, he fails to acknowledge that change does not come easily, that institutions are fragile, that progress depends on taking small steps, not giant ones. I fear that Robinson’s socialism, with its proudly utopian characteristics, will hurt the very people it so wants to help. It should be tempered with moderation and cool reason, and an appreciation for the flawed but redeemable capitalist system. Yes, markets require some regulation, and yes, there are those in corporate America who insufficiently recognized the interests of stakeholders. But is this reason to throw away an entire system? I think not. Let us be reasonable. Our politics has been captured by a corrupt tyrant, but this is no cause for swinging radically in the other direction. We simply need to restore that which is good in our politics, in our constitution, and our economic system. Historically, American prosperity has been for everyone, and we have worked together to build a great country of estimable values. True patriots recognize what real American values are, and work to steadily improve a “greatness” we have never truly lost.

The Marxist’s Review

The standards of the bourgeois publishing industry are, of course, low, but one might expect a book about “socialism” to evince some marginal understanding of socialist theory and praxis. One might not demand the author to have read the full Grundrisse in the original German (I have), but could one not at least presume he will possess a working familiarity with Capital and the materialist conception of history? In fact, one could not and should not, for the bourgeois publishing industry is a servant of capital and is only capable, by nature of its relations of production, of producing a bourgeois explanation of socialism. This book shows the grotesque contradictions that result when capitalist industry attempts futilely to resolve its internal tensions through the commodification of socialism itself. It can barely even be evaluated as a text, but solely as the mangled and hideous product of a dying system’s desperate attempts to neutralize the class struggle. This book may not tell us a single fact about socialism, but in its existence as an object of the production process it does offer confirmation of the scientific character of Marxist theory.

It should go without saying that Nathan J. Robinson is not a socialist. Nor is he a thinker, a writer, or a public intellectual. He is certainly not a dialectician. Robinson’s “socialism” is a mutilated ahistorical hodgepodge of neoliberal nostrums. It shows scant awareness of historical scholarship, and proceeds upon the unspoken mistaken assumption that the bourgeois state is capable of advancing socialism. Indeed, the irreconcilability of emancipatory class struggle with reformist parliamentary politics, a fact central to any understanding of the dynamics of capitalism, is unmentioned in Robinson’s book. Robinson wears his utopianism as a badge of honor (he believes the future will contain friendly megafauna and seas of lemonade), and we should take his book exactly as seriously as he takes questions about the organizational development of working class consciousness, i.e., not at all.

It is no accident that Robinson’s book neglects global socialist movements, erasing the history of African, Islamic, Asian, and Latin American socialisms in favor of discussions of Eugene Debs and the Milwaukee “sewer socialists.” A tacit imperialism undergirds the whole framework: Instead of examining capitalism as a global system of extraction, he discusses “inequality” of “distribution” within the boundaries of the United States, thereby not only decimating any chance of actually understanding the productive base of the system he claims to be explaining, but putting forth what is actually a defense of the existing order disguised as a critique of it. It is telling that one of Robinson’s examples of “pragmatic utopianism” is the abolition of international borders, no proposal being more dearly favored by the owners of capital. This book certainly contains proposals that will please ruling class sensibilities (his professional-managerial colleagues will see their private-school student debt wiped away) but contains no structural analysis of power and no revolutionary consciousness. It is no understatement to say that Robinson makes Elizabeth Warren look like Kwame Nkrumah.

The Manatee’s Review

As a sea-dwelling herbivore, I find this book about American politics to be of little practical use. Of what possible relevance to a manatee could a book about socialism be? I found reading the book a nuisance, an unwelcome interruption to a life of placidity and repose. I longed to return to my usual habits of nibbling kelp and avoiding speedboats, to snuggle other manatees and to wander aimlessly through coastal inlets. I trouble no one and ask nothing but to be left in peace. Why was this review copy sent to me? Of what earthly use could my opinion be? Have humans previously turned to manatees for literary advice? Have they shown the faintest sign of curiosity regarding our inner lives, let alone been willing to treat our written testimonials as valid and helpful? They have not. I do not expect them to start now. Please remove me from this list and cease to pretend that your kind has any interest in our thoughts and feelings. It only adds insult to airboat injury.

Why You Should Be A Socialist contains nothing at all about manatees. It is a political diatribe about the idiotic and eminently solvable social dysfunctions of a species whose existence is regrettable to all others. I can neither recommend nor condemn it, for it is of no earthly importance to me. There is, however, a picture of a seahorse on page 72, which gave me a fleeting burst of satisfaction.

The Me’s Review (aka My Review)

I should confess that I have something of a bias in reviewing a book by me. Personally, I thought it was excellent, exactly the sort of book I would have written if I were myself, which of course I am. Nevertheless I shall try to exercise my critical faculties, and tell you, looking back over the book, what I genuinely think I did well, and what I think I did somewhat less well, and give you my own take on my strengths and weaknesses as an explainer of socialism.

Here’s what I’m proud of: The book covers a lot of ground, and it synthesizes many arguments I’ve made on many different topics for the past few years. From beginning to end, you’ll get: a survey of the rise of millennial leftism, an explanation of the sources of socialist philosophy, a diagnosis of the ills of the current economic system, some forays into the grand tradition of socialist thought and practice, some descriptions of possible socialist utopias, some practical explanations of near-term socialist policies and tactics, a dive into the problems with both liberalism and conservatism, a refutation of common criticisms of socialism, and a rousing battle cry for the new generation of socialist activists. It manages to talk about heavy political topics in a clear and lighthearted way, and it’s got some really good bits of writing in it. There are tons of great quotes and sources along the way, so that when you finish reading there’s plenty more for you to check out. I’m especially pleased with the appendix, which lists lots of excellent left writers and podcasts. There are so many smart people writing and broadcasting from the left these days, and I’m excited to introduce them to larger audiences, because they’re heard from so little in the “mainstream” outlets.

Does Why You Should Be A Socialist succeed? I think it does do what I set out to do, which is to present a clear introduction to basic left principles, show why leftists have a problem with the existing structure of the economy and society, encourage people to imagine alternatives, offer a basic overview of the existing left political agenda, and reply to some standard objections.

But it’s also very imperfect. Having to cover a lot of ground means that some of it is very superficial, sometimes to the point of absurdity. (E.g., a paragraph on animal rights, very little history, sketchy theory, hardly anything about socialist movements around the world.) I realized once I’d started writing it that I had set myself a task at which I was destined to fail. Nobody could write a wholly satisfying 300 page book that covered all of politics and economics and left political history and strategies and programs around the world. I was very overwhelmed in the writing process: My God, I haven’t discussed Native issues yet. I haven’t discussed school privatization. I haven’t dealt with capital flight. When I had finished a first draft, I looked at it and felt moderately satisfied, then realized I’d produced an entire book on socialism without a section on Karl Marx, history’s single most influential socialist. So I had to go back and write one. To the consternation of my publisher, I kept trying to go back and add new material, to the point where at a certain date they had to say “ENOUGH.”

I also think I contradict myself a bit in the book, especially where I try to figure out the difference between socialism, social democracy, democracy, etc. In my defense, one inevitably gets in a muddle when trying to discuss terms that people use to mean different things, and I do think I did the best I could. But perhaps I should have gone back and really ruthlessly scrutinized and refined my arguments to make the whole thing airtight. It is a bit leaky as is, and might even misuse a term here and there.

I even committed a few errors. I referred to the Democratic National Convention as the Democratic National Committee and said the NHS started in 1945 when it started in 1948. These were oversights rather than ignorance—I’ve even written about the founding of the NHS—but when you make small mistakes like this, it is easy for someone to make you look lazy and foolish. Unfortunately, when you write a 75,000 word book, with perhaps 400,000 letters/characters in it, it is difficult to achieve perfection. Publishers copy-edit, but they don’t fact-check, so it’s up to the writer to make sure that every statement in the book is actually true. I did my best. There are likely some blunders. (Also, in the chapter on conservatism, I try to be a little generous by talking about environmental conservationism as a kind of conservative thinking we can respect. In doing so, I mentioned “Theodore Roosevelt’s conservatism” as respectable without noting that he was also a man of openly genocidal beliefs. That was a mistake, but it’s what I get for trying to soften my approach to conservatism.)

Because Why You Should Be A Socialist is full of provocative statements that will piss off people of many political persuasions, I am sure I will get some savage critiques (assuming people care enough to read it). I may respond to some of those if it doesn’t feel like a wearying waste of time. But I would like to address some of the criticisms made by my fictitious reviewers above.

The Libertarian sings a series of familiar tunes about the wonders of free markets. I think what’s important to note about libertarian rhetoric is how good it can sound, when you don’t think about what it actually means. Leave people alone: great, hooray! Don’t interfere in contracts: right! Interference, who wants that? Don’t tamper with prices: No, tampering would hurt the economic signals. But then in practice what these things mean is: Leave employers alone to fire people for getting sick, don’t interfere in contracts that require employees to let their bosses spy on them 24 hours a day, don’t prevent landlords from raising the rent by 500 percent in a single month if they feel like it. Every libertarian says the same thing: No, capitalism isn’t about greed, but then they say that the “pursuit of self interest” is neutral or desirable. Honey, that’s another word for the same damn thing.

The Libertarian’s review also simply repeats talking points that are thoroughly addressed in the book. It might seem persuasive to you now, but only because it portrays my socialism as far less sophisticated than it actually is. Amazon can simultaneously be giving customers what they want and ruthlessly exploiting its employees in order to do that, and what we want are institutions that serve everybody and do not depend on underpaying and overworking people. I have written elsewhere about why we believe in decommodified “free at the point of use” services—it is not because we are under the illusion that no work or resources are required to provide them. We know that libraries and firehouses have to be built and staffed, but we also believe that life is better for everyone when “whether your house will be protected in case of a fire” or “whether you can see a doctor if you get sick” is not something determined by market exchange. Why You Should Be A Socialist shows why it is the concept of “consumer choice” as true freedom that is “topsy turvy,” and while it’s true that I as a single individual cannot provide a full blueprint for an optimal society, I do offer some principles for how we can judge whether we are making people more or less free in a meaningful sense.

The Liberal simultaneously believes that socialism is radical and that the things socialists believe are “actually” simply liberalism. Are socialists hotheads who want to overthrow the system? Or are we “just social democrats” who are rebranding progressive liberalism as radicalism? I firmly believe, and I explain in the book, that there is a meaningful difference between liberalism and leftism, and you can see it here in this review. We leftists do not share the rosy view of American history that the liberal has, seeing it as a story of cheerful upward progress interrupted by the aberration of Donald Trump. And we believe that big changes do not come about without correspondingly large ambitions. We envisage not just slight improvements, but the elimination of social classes and giant imbalances of power between people. It is true that our values may often sound like those of the Liberal, and many of them (such as free and open discussion) do overlap, but as we can see from looking at the Obama administration’s approach to politics or the Democrats’ hostile reactions to Bernie Sanders’ campaign, we do have very different values and visions.

The Marxist is difficult to reply to. How can one disprove these charges? There are a few good points here: I wish I’d written more about international socialism (the short section I did write was cut for space reasons) and issues of global economic justice. But I do think this perspective is too cynical about the possibilities for what can be done through existing government structures. The truth is, we don’t really know what transformations our democracy is capable of producing. Perhaps my Marxist reviewer is right. But I do not see what the alternative is. (In writing this, by the way, I do not mean to snark too much at my Marxist friends. It is a particular style I am taking aim at. Specifically, I am channeling the Marxist Left Review’s vicious review of Bhaskar Sunkara’s Socialist Manifesto, which to my mind was about as unfair of a hatchet job as a book review can be.)

The Manatee is probably right. All of the animals are right. How ignorant we are of their concerns, how little we think about what they want or deserve. Someday I will write a book that makes the manatees happy. This is not that book.

As for Me, I think this review is even-handed but a little too self-referential.

Why You Should Read “Why You Should Be A Socialist”

So there you have it: Nobody likes Why You Should Be A Socialist. Or at least, nobody except me. But perhaps you will like it. In fact, I think there’s a strong chance that you will. It’s fun, it’s informative, it’s practical, and parts of it are quite moving. Perhaps you’re not a socialist yet. No matter. That’s why I wrote the book, after all. So pick it up. Give it a chance. Argue with it if you must, but please forgive me some small mistakes and don’t listen to what the reviewers say. Judge it for yourself, charitably and carefully. It’s not a perfect book, and it probably even has some major flaws. I bet I got a statistic wrong here and there. But try to look at the big picture and give the case I make some thought before you rush to denounce it. Before you tear apart every footnote and document every omission, give me a chance.

The socialist creed is that “a better world is possible.” I want you to believe in that creed. I think it will make you happier, that it will give you something beautiful and valuable to fight for. I think you should respond to problems with socialist thinking by helping all of us become better and smarter socialists, not by embracing a system where market prices determine human values. So get a copy. Get your friends copies. Get your enemies copies. Then come and join the socialist movement.