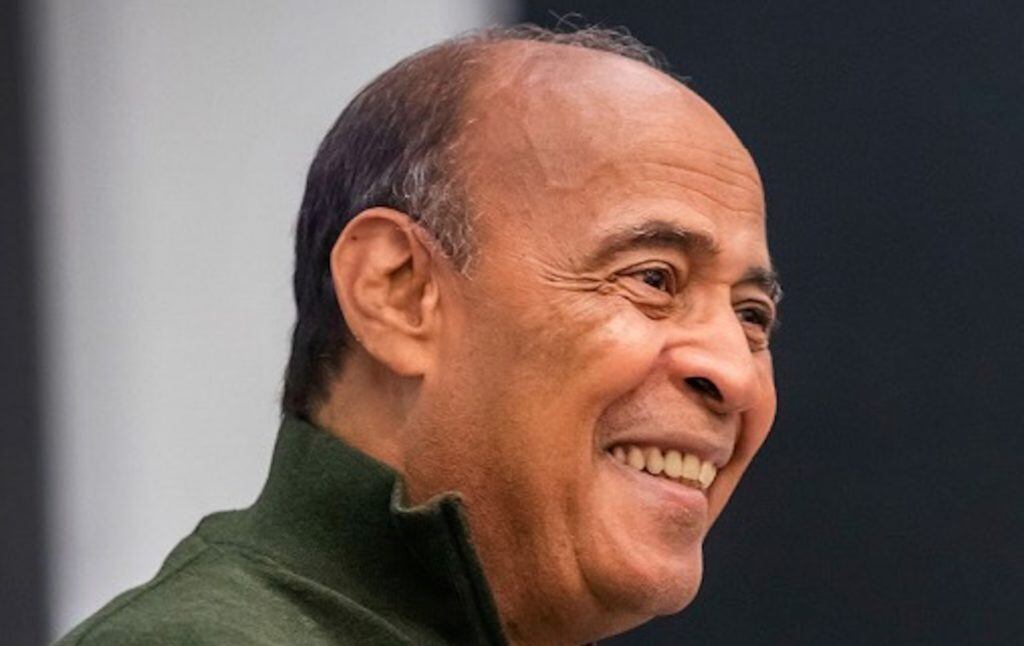

Adolph Reed, Jr. is Professor Emeritus of political science at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of a number of books on American politics including Stirrings in the Jug: Black Politics in the Post-Segregation Era, The Jesse Jackson Phenomenon, and Class Notes: Posing As Politics and Other Thoughts on the American Scene. He spoke recently to Current Affairs editor Nathan J. Robinson at the Current Affairs headquarters in New Orleans. The interview can also be listened to or watched on video. The transcript has been edited for grammar, length, and readability. The interview was transcribed by Addison Kane.

Nathan J. Robinson:

I was just re-reading Class Notes, and I was trying to think of the common themes that I see running through your writing. The subtitle of this book is Posing As Politics and Other Thoughts on the American Scene. And one thing you often write about is what politics is and what it isn’t, and how many things look like they are meaningful political action, or are treated as if they are meaningful political action but really aren’t. And they can delude us into thinking that we are making progress when we aren’t. And for 30 years in your writing, from The Jesse Jackson Phenomenon, through the Million Man March, through Obama, you’ve been documenting these sort of phenomena that look like large-scale social change, without actually moving power.

Adolph Reed:

Right. I think that’s very well put. And from one perspective, it could be kind of depressing that I’ve been saying the same thing for over 30 years. At the same time I’ve railed against what I’ve called “the myth of the spark,” the tendency to think that some exogenous intervention is going to happen to knock the shackles off people’s eyes, and the masses will then rise, I realize that at least since 2016, I’ve been charting, as it were, the increasing ideological boldness on the part of the vocal segments of the people of color, professional and managerial class… who make clearer and clearer, almost daily—I don’t know if you’ve been following the hype for the Essence Festival here [in New Orleans], coming up…

NJR:

Oh yeah. Michelle Obama, guest of honor.

AR:

Yeah, yeah, totally. But they make it clearer and clearer on a daily basis that their politics is exclusively a class politics, right? And I realized that I have caught myself thinking, surely they’re so brazen now that it will be clear. And it just finally hit me, “well, that’s only another version of the ‘myth of the spark,’” because there’s no objective moment when a crisis occurs. So I guess that makes me feel a little better over the last 30 years.

NJR:

I want to dive a little more clearly into what you mean by “a class politics.” One of the things that also recurs is your objection to “identity politics” or “race reductionism.” You say it obscures really, really important divides within black politics, and that those divides are essential to understanding black politics, and it sort of treats black political actors, and black people themselves, as a hive-mind monolith, and it’s racist in its way, and when you break it down, the class divides in black politics are extremely important to understanding what is going on.

AR:

Yeah, absolutely, you could be my press agent, basically.

NJR:

I mean, I’ve just been reading your books [laughs].

AR:

Yeah, and among the ways that the class divides are consequential are, for instance, the current obsession with the New Deal as “racist,” and with the idea that universal programs are fundamentally racist because they don’t target black people in particular, and black people don’t get anything out of it. But the fact of the matter is, black people got a lot out of the G.I. Bill, black people got a lot out of the WPA (Works Progress Administration), black people got a lot out of the Civilian Conservation Corps, and that racial disparity isn’t in the distribution of benefits, and good things and bad things, isn’t necessarily, like, the end of the story. This notion that Medicare For All, a single-payer health system, wouldn’t do anything at all for black people, because it’s not race-targeted, the idea that free public college wouldn’t do anything for black people because it’s not race-targeted, are clearly class-based programs.

NJR:

I think the justification for universal programs like Medicare For All and Universal College is sound, completely. But I would then ask you whether you think there are any programs that need to be race-targeted. So, let’s bring up reparations, which a number of people on the left have been saying should be a part of a left agenda, because it specifically addresses a giant racial injustice that has never been corrected. Last week I was talking to Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, who was telling me, well, you can’t fix the racial wealth gap, unless you have some kind of program that targets a deprivation that was racial. Is there a way to close the racial wealth gap through things that are just universal?

AR:

Well, it’s interesting, because I was just on an NPR show with Keeanga a few weeks ago. They called it a debate, I call it a discussion, but on the reparations issue my first question has always been the same, and I’ve never gotten what I thought was a satisfactory attempt to answer. Which is how can you imagine, in a majoritarian democracy, putting together a political alliance that’s capable of prevailing on an issue like this, that no one gets anything out of, except black people. And that’s even before any of the other questions, like, “what counts as reparations? Who gets what? Should the ADOS (the American Descendants Of Slaves) line be followed? What about all of the other harms?” So there’s all that. I do think that, just from a pragmatic political point of view, the pragmatic political question trumps it. And I know the response has always been, “well, don’t you think black people deserve something?” And I say, well, yeah, of course, but that’s not the issue. The issue is what is possible to win, and how you can win it.

NJR:

It strikes me, though, that a lot of the things that we demand on the left are radical and require shifting public consciousness. Often, at the beginning, they are things that we can’t imagine, or it’s very difficult to imagine having. The fact that the majority may be against you means that you have to work very, very hard, and it’s a very slow process. But if that’s what would constitute justice, it’s sort of necessary, because there’s lots of things that majorities oppose, but we believe in protecting minorities. How do you think about things that are of practical utopianism, versus things that are utopian utopianism?

AR:

Yeah, I hear you, and in fact, Keeanga brought up the case of abolitionism. And that’s a nice case, because it shows the problem with the argument. Abolitionism didn’t get anywhere, really, except to piss off slaveholders, until political circumstances shifted to advance the position of political anti-slavery activists, and anti-slavery Northerners were opposed to slavery for a lot of reasons, some of which, of course, overlapped with the abolitionists’ moral concern, but for other reasons that they could see their own interest in: both a commitment to an ideal of free labor, sometimes racist and sometimes not, and anxiety about being degraded by an immigrant labor force. A lot of other things have been like that, too. For reparations in particular, what we would have to do is convince people whose main experience, or one principal experience, is a declining standard of living and increase in economic insecurity, to go to the wall, fighting for an agenda that they, by definition, wouldn’t get anything from. I just don’t see how that’s possible.

NJR:

Is it ever possible to mobilize around something that is not in people’s self interest? I mean, we don’t want to always have to appeal to self-interest. There are things where we’re going to have to pursue where people are going to have to give something up, or…

AR:

My take on this is that is this: I read Aesop’s Fables a lot when I was a kid, and one of my favorite ones was the one about the contest between the wind and the sun [The North Wind And The Sun], and they were boasting back and forth at each other, and they determined to test their prowess against a wayfarer who was walking along the road, and whichever one could get him to take his coat off would be the more powerful. So the wind blew, and blew, and blew, and no matter how much harder the wind blew, the traveler just kind of pulled his coat more, and more tightly around himself, and when the sun took its turn, and just sort of began to radiate more and more warmth, the traveler eventually took the coat off on his own. My approach to politics, and this goes back to what counts as a movement, and what doesn’t, is the project of trying to fasten a broad-based political alliance in which different people and constituencies can not only see a vehicle for pursuing their own interests, but can come to understand that a condition for advancement of their own interests is an equal commitment to advancing their partners’ interests. So, from that perspective, I don’t understand how we build solidarity by going around the room to stress how profoundly we actually differ from one another.

NJR:

I want to talk to you about Obama, because I have here this prophecy you wrote in 1995. You don’t mention him by name, but we all know who you’re talking about.

In Chicago, for instance, we’ve gotten a foretaste of the new breed of foundation-hatched black communitarian voices; one of them, a smooth Harvard lawyer with impeccable do-good credentials and vacuous-to-repressive neoliberal politics, has won a state senate seat on a base mainly in the liberal foundation and development worlds. His fundamentally bootstrap line was softened by a patina of the rhetoric of authentic community, talk about meeting in kitchens, small-scale solutions to social problems, and the predictable elevation of process over program — the point where identity politics converges with old-fashioned middle-class reform in favoring form over substance. I suspect that his ilk is the wave of the future in U.S. black politics, as in Haiti and wherever else the International Monetary Fund has sway. So far, the black activist response hasn’t been up to the challenge. We have to do better.

And that was, in fact, Barack Obama you were referring to.

AR:

Oh yeah, totally. I’ll tell you what happened. I always say that it’s often more important to be in the right place at the right time, and to keep your eyes open, than it is to be smart. And I lived in that state senate district, I worked very closely with his predecessor, and we actually had an organizing campaign going in that state senate district, to try to do civic education among the constituents about what the difference between the state house and state senate, how a bill becomes a law, et cetera, et cetera, and then Barack popped up. Nobody knew anything about him, nobody in the activist world had ever heard of him, had no connection to him, and it was just fascinating watching the Hyde Park liberal and foundational world—I don’t know if I can say this—but get kind of wet-pantied over him. And it actually split the left in that part of the city as well. My good friend and Dr. Quentin Young, was one of the stalwarts who supported the incumbent, whose name was Alice Palmer, a very, very good person, against Obama, and we just sort of watched it play out over the intervening decades.

NJR:

I want to dwell on the line that “the fundamentally bootstrap line was softened by a patina of the rhetoric of authentic community.” It’s interesting that one of Obama’s big pitches was that his roots were as a community organizer, that he came from, supposedly, the organizing world, but you point out that was actually kind of the opposite of the truth. Also, the “bootstrap thing” you dwell on—you wrote in an essay that I have here in 2008, while he was actually running, called “Obama No,” where you talk about the way that he used fundamentally very conservative rhetoric, especially when he was talking to black audiences, using the victim-blaming message of tough love, about behavioral pathology in black communities.

AR:

Yeah, that was really striking. And especially, in the summer of ’08 after he had all but officially sewn up the nomination, he made an immediate sharp-right turn over the span of four, five days, just weighed in on the pending Supreme Court decision that ultimately invalidated the Washington, D.C. gun control statute, and he was opposed to the statute. I’m trying to remember what the other two were. But then what got me was, perhaps most of all, with the Philadelphia speech so many liberals touted as his acknowledgment of structural racism, because he made a reference, in passing, to patterns of inequality that got formed in the 1930s, and had then been reproduced over time. But the rest of the speech was a version of the “broke black people aren’t worth anything,” that they need to modify their behavior, that they need to—I can’t recall if this is when the infamous “cousin Pookie” was born,* but as some friends of mine pointed out, there’s no way in the world that Obama ever had a cousin Pookie.* It was striking that Obama seemed to burnish, if not to establish, his bona fides with the black political elite by giving the “tough love” speech, as if it were a first person plural, that “we” have to tell our broke people to do better. It’s just kind of striking.

*[Obama had told black audiences that they needed to talk to their “Cousin Pookie” who sits on the couch and doesn’t vote.]

NJR:

You did this big Harper’s cover story in 2014, called, depressingly, “Nothing Left.” And you present Obama as the culmination of a tendency that had been going for a long time, a sort of final triumph of Reaganism—in that, for most of the 20th century, there had been a left. It hadn’t been a successful left, necessarily, but it had existed. But from Reagan to Obama, the left just sort of withers and dies. And by 2014, when you’re writing, it’s a year before Bernie Sanders’ campaign. That was a very bleak moment.

AR:

It definitely was. It’s still bleak. Trump is in the White House, and many of the Democrats are fully committed to doing whatever they can to put him back there. Bits of that essay came out of the first chapter of my long-suffering book that began as a book on Obama mania. Tariq Ali of Verso approached me right after the election. I didn’t want to do an Obama book, but I thought, “okay, I can do a book on Obama mania,” because one of the head-scratching moments of this phenomenon, was seeing how many people, who you would think, based on their histories and practices, would know better, got swept up in this ridiculous hype about this guy

I first felt anxious that Obama might actually break the mold and do something that I would not have imagined he would do, maybe find his closet FDR or something, and stand for something. So I felt kind of anxious, kind of waiting to see what happened every day, and then I finally said, “look, the book that I really wanted to do, and the book that answering this question”—that is why did so many people who should have known better get swept up in the hype?— the book that is really required to answer the question is a different sort of book on the decline and the transformation of the left in the U.S. since the end of World War II. It attempts to address what it was about what’s happened to the left that even led serious, longtime veteran activists to delude themselves, and to delude themselves as militants. It’s not just that they liked Obama, and supported Obama, but they were sort of like, the Gestapo for Obama during the campaign.

NJR:

Well, yeah. I wouldn’t quite use that term, but I just reviewed the memoirs of these guys that worked in the administration, and one of them says, explicitly, “my friends all started to say ‘you’ve become this unthinking, Obama-bot,’ and it was kind of true.” He says, “I was an evangelist for Obama, I didn’t really know what he stood for, but I just liked him so much, and I became obsessed with him, he just had this incredible power.” I mean, I’m a little sympathetic to this, because some of it comes out of desperation. You point all through your work to things that aren’t political movements that want to be political movements. But some of the time, it’s because no one knows what to do, so they cling to what seems like politics. It seems like it’s advancing justice. And the election of Obama seemed like a very radical transformation, and once it came into the realm of possibility, it’s understandable why people would say, “wow, we can do this incredibly transformative thing.”

AR:

True, but that, to me, is the most depressing thing in the world. That’s like, frighteningly depressing. That’s—being in that position, where you feel so desperate, where you have to turn to a fantasy to get some solace, to me, feels like sort of leaping into a religious commitment, because you can’t face the world as it is, which to me feels like the same thing as being buried alive.

Look, there are moments when the political situation is absolutely hopeless, and there are such moments, and that’s when you assassinate the fascist judge, or flip the bird to the eagle that’s coming down on you, but I don’t want to rush that moment. There’s nothing beautiful about that moment. And as I’ve said in a number of places, my approach to politics is like how they teach kids to play the outfield in little league baseball, where on the deep fly-ball, you go to the wall first, and feel for the wall, and then come back into the ball. So you imagine the worst possible thing that can happen, and figure out how you would adjust to that, instead of looking for a fantasy to get you through the night. Because, to me, that just feels like a dilettantish way of doing politics, because you’re not really committed to winning anything, and there are no stakes for you. I have a friend who organized in Brazil under the dictatorship, in the underground. There were stakes in politics, then. The politics of performance of individual righteousness just always seemed distastefully Protestant to me, you know what I mean?

NJR:

So, what is a politics of performance? Give some examples of that.

AR:

Well, it’s like, the various versions of “having to take a stand.” Seeing politics as having to take a stand about something, seeing politics as a domain more for personal expression than for organizing, or for colloquies of the converted, basically, in contrast to trying to figure out ways to talk to people who don’t already agree with you, like we were talking about before.

NJR:

You’ve written about, for instance, in New Orleans, the push to take down all the Confederate monuments. I don’t know where you stand on whether or not we should keep them or not, but the bigger issue that you raise is that we have to always orient our political program toward getting material gains for people, and things that aren’t getting material gains for people, and that aren’t linked to, even theoretically, some kind of program for actually redistributing wealth and power, ultimately can’t go anywhere.

AR:

I think that’s right. I’ve been trying to think through my new relationship to the statuary for a long time. I mean, I have kind of a funny background in the sense that I’m sort of half local, half northeastern, for complex reasons. What that meant was that I was always, even as a kid, acutely aware of all those monuments, and what they stood for, and hated them, and hated every one of them. And then when they actually began to come down, or when the discussion about taking them down heated up, after Nikki Haley finally took the Confederate flag down from the state house grounds in South Carolina, I found myself feeling a little bemused, because obviously, I’m glad they’re gone. Every time I walk past Jeff Davis Canal, or walking in the park, which is like a long block and a half from my house, and there’s no P.G.T. Beauregard—well, I’m happy! So, it’s better for them to come down than not to come down.

But in a way that celebration is kind of akin to the celebration of Obama, in a couple ways. One is, going to Obama, the idea that the black president was elected was like, a big victory. Well, I guess. I grew up like everyone else in America, saying any kid can be president, except a black kid. Well, but obviously demographic, and ideological circumstances changed in a way that makes it possible for a black guy to get elected. So, in that sense, the change has already happened. And it’s not like he was made Pope. He put together an electoral coalition in a particular set of historical conditions, and I still would not be surprised, had the bottom not fallen out of the economy at the moment it did, if McCain could have won that election. Maybe not with what turned out to be the colossal misstep, or miscue, or mistake of thinking that they could get like an Elly May Clampett bounce from having Palin on the ticket, which was kind of cute and funny for a while, but when the bottom fell out from the economy, her mulish narcissism became so apparent. But anyway, he won, and he won again, great. It was good that the monuments came down. But they also came down in a discourse of triumphant local neoliberalism, that sort of links an ideal of racial justice to market idolatry. And it didn’t have to be that way, but it was that way.

I mean, in the best of all possible worlds, I would have preferred something like a six-month or a two-year public information campaign about what the Confederacy was, and what the Jim Crow era was, and whatnot, but you can’t always have history the way you want, when you want it. It’s fine that it happened, but we also saw that the Take Em Down NOLA coalition had no other program, so once those four monuments came down, like all they had was taking down more of them, and changing all of the street names. The real marker of insanity was that their next big move was to take down the Jackson statute at Jackson Square. That was kind of a give away that they were a group from out of town, because that image is so iconic to the entire tourist effort, and has been for a century, that it was just a colossal misreading.

NJR:

Another thing that you talk about a lot, which is the effort to make inherently unjust institutions look progressive, and to diversify the board of Goldman Sachs, so that we don’t recognize the function and the role of Goldman Sachs. Elizabeth Warren just signed onto this call to have gender parity in the upper echelons of the U.S. military, but you can’t fix the military-industrial complex through making sure you have the right people in it!

AR:

Totally, totally. And this is another marker of the decline of the left, ultimately… [This model of a just society] presumes that a society can be just if 1 percent of the population controls more than 90 percent of the good stuff, provided that 1 percent is like 12 percent black, 14 percent hispanic, half women, and whatever the appropriate percentage is gay. And I can’t say that that’s not a just society, or that’s not a legitimate model of a just society. Is it a model of a just society that most of us want to sign up for? Probably not. And I think that the politics that we need to cultivate as a left, at this point, is a politics that makes very clear that there are these two competing models of a just society. They’re not compatible, except in the sense that sure, if a world in which the ruling class is diverse, and the world in which the ruling class isn’t diverse are the only two options, then yes, for people with egalitarian interests, the former is less obnoxious than the latter. But if people have really egalitarian interests and concerns, then the proper response is to demand some other options, and a different understanding of what a just world is. And that, to me, is the fundamental political objective.

NJR:

I want to talk about what political action is, because you talk about how doing things well is difficult. Real organizing is painful, it’s slow, it involves making yourself uncomfortable, your victories are not going to be easy. And one of the things that you say here, in the introduction to Class Notes is:

the movement that we need cannot be convoked magically overnight, or by proxy. It can’t be galvanized through proclamations, press conferences, symbolic big events, resolutions. It can be built only through connecting with large numbers of people in cities, towns, and workplaces all over the country, who can be brought together around a political agenda that speaks directly and clearly to their needs and aspirations. It is a painstaking process that promises no guarantees or ultimate victory. But there are no alternatives other than fraud, pretense, or certain failure.

AR:

Yeah, I’ll stand by that. I guess I could have included self-delusion, with fraud and pretense, to be a little bit more charitable. But yeah, I think that’s what it comes down to. And look, I was just thinking about this. I was joking with someone not too long ago. On the Sanders campaign trail, last time, it felt like a fair amount of my effort was to try to equilibrate the passions of the young, exuberant Berniecrats—the sort who would go off, after a day of canvassing, and get a tattoo on their arm. They tended to rise and fall, with every news report, what’s happening in the Iowa polls, or what’s happening with what Clinton said or did, and I found myself giving them the story of Sergeant Pavlov at the Battle of Stalingrad, that these 25 troops held a building for 58 days against multiple daily Nazi assaults, and they were focused on what their job was, and their job was to hold that building. And the campaign workers’ job was to do whatever they had to do that day, in whatever locale they were working in, to try to broaden the base of the campaign by a handful of people, and it didn’t matter what was going on in Wisconsin, or what Clinton had said. Their job was going to be the same no matter what, because the only way to build a campaign is through that kind of work.

That was the ethos that we took to try to build the Labor Party, and we held firm on that. But there were a number of really good people who I knew, mainly academics, who just couldn’t understand why we were averse to trying to get coverage in the New York Times, or whatever. And my reaction was, because we’re a working class initiative, they’re never going to give us good coverage— the only thing they’ll ever try to do is smear us, and that’s not where we’re going to build our base. We’re not going to build our base by wooing Krugman and the editorial board of the New York Times. We’re going to build a base, and it’s just like something Sanders said in the first debate: The only way we’re going to make any of this stuff that we want happen is to build a popular movement out of there that’s big enough, and strong enough to assert its will in a way that can change the terms of the political debate.

I often point out that for most of us who are concerned with egalitarian interests, we actually got more from Richard Nixon than we got from any of the three subsequent Democratic presidents, and it’s not because Nixon liked us. I’m pretty sure he hated all of us, but the fact was that the balance of political and social forces in society was such that Nixon understood that ours were interests that he had to accommodate in some way.

NJR:

How much potential do you think Bernie Sanders has?

AR:

I go back and forth. The longer that the campaign is alive and viable, the more opportunities we have to organize through it, and underneath it, to try to build a popular base on the issues. And Sanders understands that, too. This time, it’s also pretty clear that all the rest of the field is more committed to defeating the left than they are to defeating Trump, and that certainly makes sense, given what we know about the rest of the field. I think it’s way too soon to say. We’re not going to know anything, really, until votes start coming in.

NJR:

You write in Class Notes of your own organizing experience in the G.I. coffeehouse movement, where you talk about that difficult reality of what it takes to achieve small goals. Talking to people, and converting people one by one. And the word “organizing” is easy to say, but maybe you could say what that actually means in practice.

AR:

A lot of times, people think it involves a bullhorn. But to me, it’s fundamentally a matter of establishing relationships with people, building standing with them, and how you create standing with them. If you’re in a workplace, there are people around who have standing with their fellow workers because they’re dependable, they’re trustworthy, and their fellow workers think of them as their sources of good judgement they can tap into. And it’s the same thing in other areas too. So, showing that you will act solidaristically with people about their own struggles, about their own concerns, that’s how you build a relationship with standing. They’ll trust you, they’ll pay attention to you, and they’ll listen to you. And of course, part of that means I’m listening to them, to find ways to connect the large political programs that you want to move, meaningfully, to people’s own concerns. Then you broaden the base, and just keep trying to broaden the base. So, I’ve sometimes joked that it can be a little bit like selling Amway, because what you’re trying to do is make connections, to bring more people into the project of advancing the common agenda.