Editorial Roundtable: Democracy and Elections

Is there too much democracy and what makes a candidate electable?

This week, the editors discuss a horrible article in the Atlantic arguing that democracy is bad. For further commentary, see this extended polemic about the article by Current Affairs editor Nathan J. Robinson.

PETE DAVIS (PODCAST HOST):

Friends, I despise this article: “Too Much Democracy Is Bad For Democracy.” Subtitle: “The major American parties have conceded unprecedented power to primary voters. It’s a radical experiment—and it’s failing.”

A quote from the article: “Despite their flaws, smoke-filled rooms did a good job of identifying candidates who could win a general election.”

That’s not remotely true! If both sides did that, then they lost 50 percent of the time! (Ipso facto of them both doing it!)

NATHAN J. ROBINSON (EDITOR-IN-CHIEF):

I swear these takes have been written every generation since the founding. Walter Lippman said this, the Trilateral Commission said this too.

DAVIS:

Walter Lippman — on my historical enemies list!

Professional vetting deters renegades. The professional filter also helps exclude candidates who are downright dangerous. The Harvard government professors Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, in their recent book, How Democracies Die, make this point forcefully. In a democracy, they argue, party organizations’ most crucial function is to act as gatekeepers against demagogues and charlatans who, once in power, undermine democratic institutions from within, as Donald Trump has done.

This isn’t true: Party organizations are bad at selecting people who are demagogues and charlatans!

ROBINSON:

We need to do a Pete’s Historical Enemies List episode of the podcast. How Democracies Die is an awful book too. I wrote about it actually.

DAVIS:

The article refers to the current primary cycle as a mess. Counterpoint: This primary is not a “mess.” It’s great — we have a lot of people fighting about a lot of things, which is the point of an election!

“Primaries shift power from political insiders to another set of elites: ideologues and interest groups with their own agendas.” But they should have agendas — that’s what politics is!

“A more formal kind of early vetting might require candidates to obtain petition signatures from state and county party chairs and elected officials.” So basically, this would be like China’s system — you must get approval from the party to run for office.

ROBINSON:

This is what party insiders really think. They’re probably still mad that AOC beat Joe Crowley. She should have had to “get permission” first.

DAVIS:

Political professionals—insiders such as county and state party chairs, elected officials such as governors and legislative leaders—are uniquely positioned to evaluate whether contenders have the skills, connections, and sense of responsibility to govern capably.

This is not true. Political professionals are not good at evaluating whether contenders have the sense of responsibility to govern. They are uniquely positioned to be at cross purposes in assessing this! Every paragraph of this is wrong.

This may seem like an argument for elitism over democracy, but the current system is democratic only in form, not in substance. Without professional input, the nominating process is vulnerable to manipulation by plutocrats, celebrities, media figures, and activists. As entertainment, America’s current primary system works pretty well; as a way to vet candidates for the world’s most important and difficult job, it is at best unreliable—and at worst destabilizing, even dangerous.

Who are these professionals? And how are they not vulnerable to manipulation by plutocrats, celebrities, media figures, and activists? Again, every paragraph of this is wrong.

ROBINSON:

I like articles like this though because they are so honest and you don’t have to feel conspiratorial. It’s all laid out on the page.

Like you’re not alleging that there are secretly sinister elites trying to keep people from exercising their free choice. They are literally publishing in the Atlantic. They’re directly insisting that people should not get to have the elected officials they want.

There’s also a really interesting thing in articles like these where they’re talking about Bernie without really mentioning Bernie. They usually talk about the “dangers of populism, left and right” and then talk about Trump a bunch, and maybe namedrop Bernie once or twice. But they make it clear that they see “left populism” as an equal threat without explaining exactly why.

SPARKY ABRAHAM (FINANCE EDITOR):

I love these arguments so much. We need to know who will appeal to people. Therefore, instead of having a competition that involves appealing to people, we should have a small and unrepresentative cabal of powerful politicians pick who will appeal to people.

ROBINSON:

It’s incredible they don’t discuss the fact that the party picked Hillary Clinton. And that was a bad idea. They picked her because the party elite didn’t have any idea what was going on. How can you write this take post-Clinton implosion?

ELI MASSEY (CONTRIBUTING EDITOR):

Plenty of liberal elites still believe deep in their heart that Clinton wasn’t a bad candidate, and if not for Russian interference, Comey, Jill Stein, Wikileaks, etc., she would’ve won.

ABRAHAM:

Plenty of them believe that openly! I don’t think it’s a crazy position in that she did win the popular vote. She wasn’t the worst candidate ever electability-wise. She was bad substantively and ran a terrible campaign and failed to turn people out where she needed to, and Bernie would probably have done much better.

MASSEY:

I kind of feel like losing to a clown like Donald Trump is a pretty severe indictment of a candidate’s electability, but it’s also true that all the other Republican candidates did too, so I’m not sure…

ABRAHAM:

Donald Trump was extremely electable apparently. Electable =/= good for either party! Anyway, the whole point of politics is to try to make certain ideas electable, right? That’s the whole damn thing.

MASSEY:

But it’s also the case that Trump is uniquely unqualified, an all-around terrible human being, with all sorts of glaring vulnerabilities and deficiencies, and the type of candidate you’d think could be totally trounced in the general if the right opponent came around, right? Or at least that’s my intuition.

ABRAHAM:

Seems to me like neither Trump nor Clinton turned out to be any less electable than any major party candidates in recent memory, it’s just that maybe there was another one who could have been more electable.

ROBINSON:

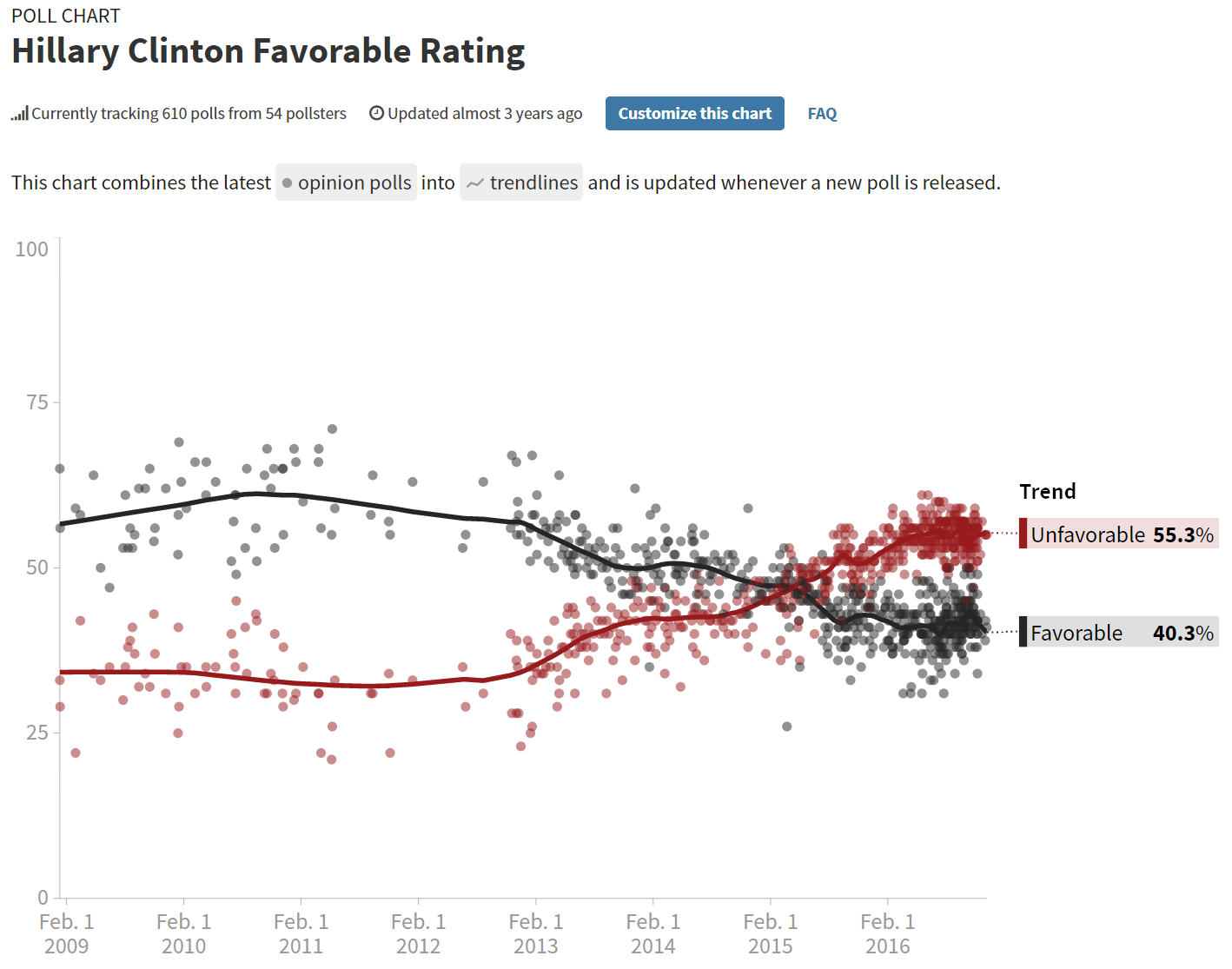

Hillary Clinton’s popular vote victory is, I think, largely attributable to people’s hatred of Trump. Compare the plummeting of her favorable-unfavorable rating over time:

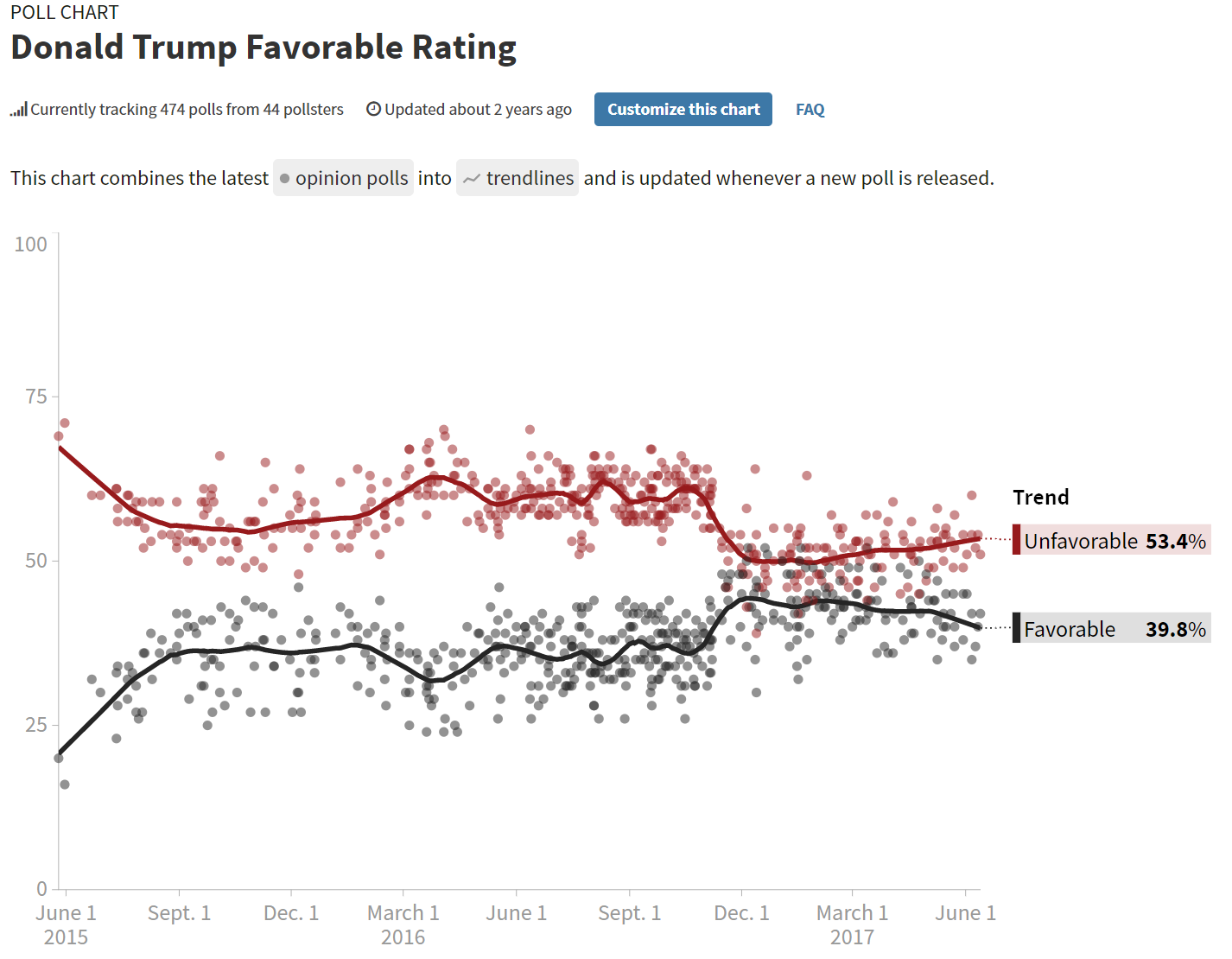

To Trump’s

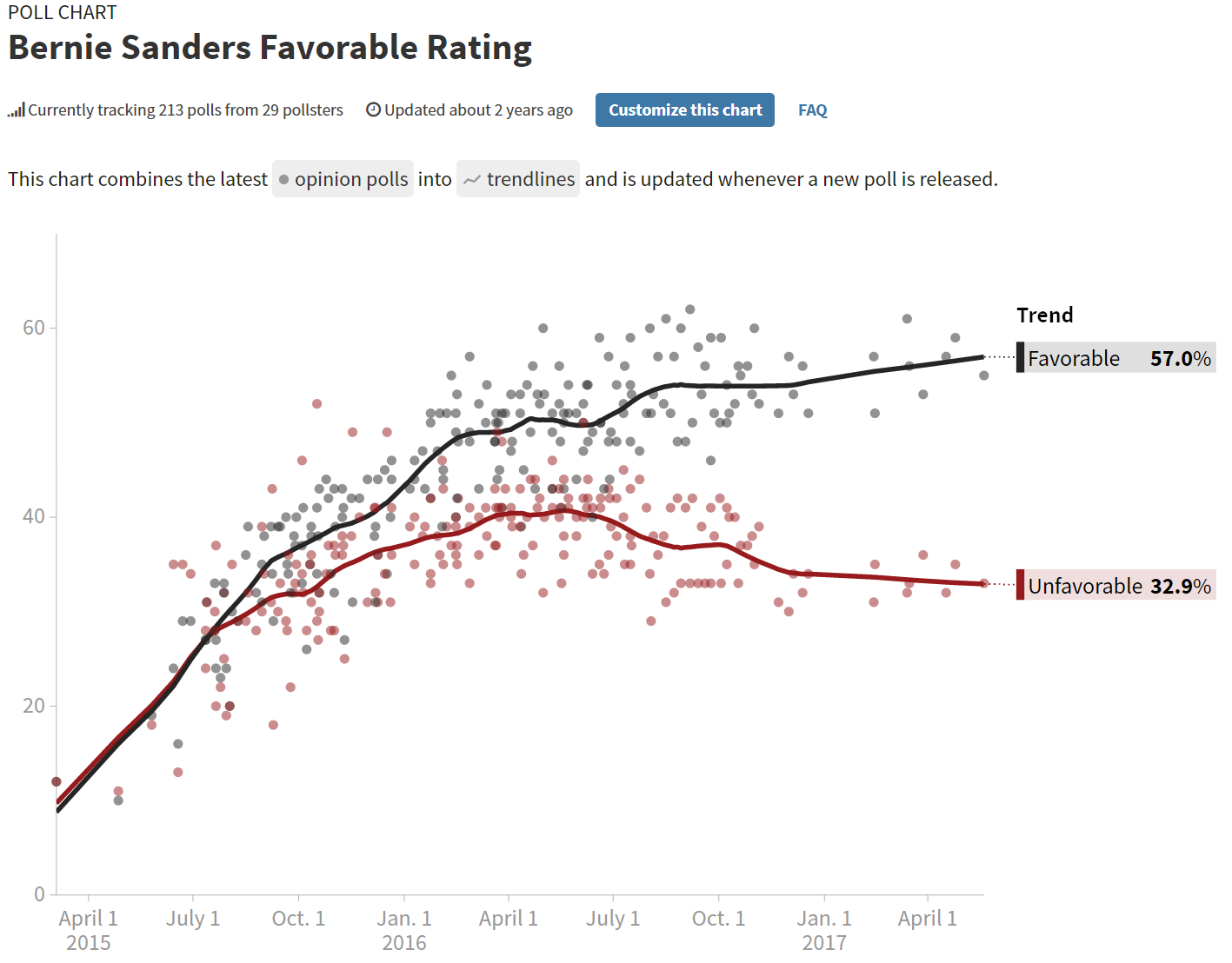

To Bernie who went from completely unknown to much more favorable than unfavorable:

I think a good rule is to pick a candidate who more people like than dislike, and who does not seem to get more disliked the more people see of them

ABRAHAM:

I think a good rule is to have a primary and in the process find the candidate with the best views and then go out and convince other people to vote for them.

ROBINSON:

Well sure, I’m just saying if we’re talking about the question of “strength as a candidate.’’ Obviously if we’re talking about best views and policies, Clinton was a horrible candidate.

ABRAHAM:

I just don’t know how to think about “candidate strength” or what the point of that is, outside of how many votes did they get. Trump won the election! Strong candidate! Hillary got a lot of votes, the most votes! Also strong, but not strong enough!

MASSEY:

I mean I think you’re right that it’s kind of difficult to conceptualize a candidate’s strength in the abstract and probably makes the most sense to consider it relative to another candidate.

ROBINSON:

My guess though would be that if you had substituted a candidate who people liked more they would have gotten more votes. That is not provable obviously, but my working theory is that the more people like a candidate, the more votes they get.

ABRAHAM:

Yeah I agree with that which is why primaries are good and party back rooms are bad. Seems like the best way to figure out which candidate people like the best is to have a big messy primary. Test whether they can get votes by making them get votes.

LYTA GOLD (AMUSEMENTS AND MANAGING EDITOR):

All that being said, Bernie did lose the 2016 primary. Yes, the DNC and superdelegates played a role in denying the primary to him, but he still didn’t get enough votes. And I think we’ll agree he was the “stronger” candidate, in the relative sense of having better policies and a higher favorability rating than Clinton. But he was still less “electable” in the sense that the party chairs who did not think he should be elected worked hard to make sure he was not elected, and to make sure he got less airtime, etc. And that’s really what “electability” is about, right? That’s what people mean when they say it. “Is this person palatable to the people in the smoke-filled room?”