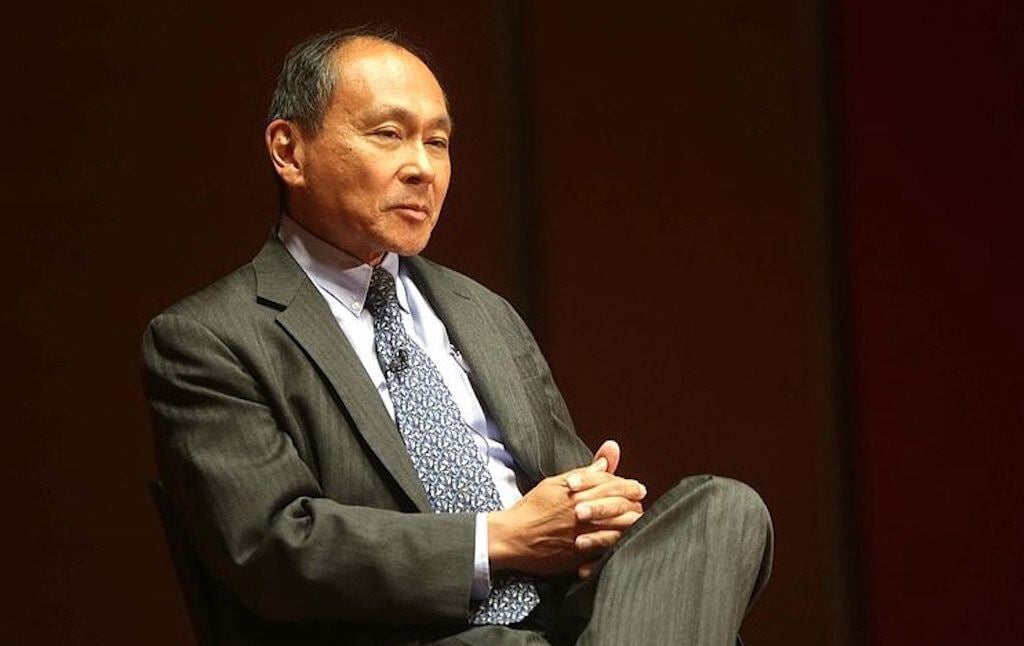

The End of Fukuyama and the Last Book

Don’t let Francis Fukuyama rebrand as a woke #resistance hero…

One of the shining accomplishments of the field of international relations—besides helping to concoct the intellectual rationale for invading other countries—is the career of Francis Fukuyama. During the 1980s, Fukuyama was one of Reagan’s top policy experts, particularly on the U.S. role in the Middle East. But he’s best known for his 1992 book The End of History and The Last Man, in which he famously declared that human civilization had reached “the end of history.” By this, Fukuyama didn’t mean that time had literally stopped, but that liberal capitalism was now the only game in town, and we should focus our efforts on trying to improve this immortal system rather than finding alternatives. For Fukuyama, the 20th century had been a battle between the ideologies of Soviet Communism and Liberal Capitalism, and Fukuyama, acting as referee, proudly raised the boxing gloves of Liberal Capitalism after Soviet Communism was TKO’d.

It’s not hard to see why eschatological claims like “the end of history” don’t really hold up after a few years. In the jittery post-9/11 context, just a few years after Fukuyama’s sweeping pronouncement, many ordinary Americans surely felt that “history” was far from over. The 2008 financial crisis, the Occupy movement, Donald Trump’s white identity populism, and Bernie Sanders’ democratic socialism are prime examples of history still in motion, of people continuing to work through the problems inherent within capitalism, and wandering both leftwards and rightwards for alternatives. Fukuyama’s undue optimism about America’s “good intentions” whenever we decide to invade another country, or our supposedly deep commitment to values such as “democracy” (while simultaneously overthrowing democratically elected governments abroad and rigging electoral maps at home), now seems as profoundly dated as horse-drawn carriages. You can imagine, then, why it was shocking to find Fukuyama riding back into the town square in 2018, hanging off the back of his stagecoach and gathering the townsfolk to try his new snake oil.

Fukuyama’s Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment was released in September 2018. Although conservatives, alt-right grifters, and centrists weigh in on identity politics literally all the time, it’s not a subject one would necessarily expect from someone with Fukuyama’s professional background, especially given the way his book pretends to frame identity politics in a positive light. Any defense of identity from Fukuyama must be viewed in the context of his career as a key policy advisor in the Reagan administration, which was responsible, at least on an economic level, for weakening trade unions and cutting funds to social programs, things that marginalized people involved in the struggle over “identity politics” tend to like.

Today, Fukuyama claims to have disavowed his former neoconservatism. In an October interview with the New Statesman, he even said:

…if [by socialism] you mean redistributive programmes that try to redress this big imbalance in both incomes and wealth that has emerged then, yes, I think not only can it come back, it ought to come back. This extended period, which started with Reagan and Thatcher, in which a certain set of ideas about the benefits of unregulated markets took hold, in many ways it’s had a disastrous effect.

Contemporary Fukuyama has successfully retrofitted his image to the “woke” politics of the 2010s. In recent years, he has been invited to speak at lefty D.C. bookstore Politics and Prose, and has given interviews around the world, including (fittingly, given his past Pollyannaism on U.S. foreign policy) one at the American University in Iraq. The title Identity sends the same message that Fukuyama has been carefully sending in talks and interviews for the past few years: He is relevant, important, and even “woke.”

But in fact, Identity demonstrates that Francis Fukuyama’s politics are still exactly the ones he had in 1982. 89 pages into the book, while ostensibly apologizing for the rise of Reagan and Thatcher, he goes on to state that “the social democratic left also reached a dead end of sorts: its goals of an ever-expanding welfare state bumped into the reality of fiscal constraints during the turbulent 1970s.” He derides the importance of redistributive policies, writing that, “political actors do struggle over economic issues,” but that “a lot of political life is only weakly related to economic resources.” Without any particular justification, he focuses instead on “status” as a political resource equally or more important than actual material interests, writing that “a great deal of evidence coming out of the natural sciences suggest that the desire for status—megalothymia—is rooted in human biology […] a further psychological fact suggests that certain things in contemporary politics are related more to status than to resources.” But calls for Medicare for All, the Fight for 15, or an increase in taxes on the wealthiest Americans are not merely desire for increased “status,” but rather issues of real material interests affecting people’s everyday wellbeing.

Fukuyama spends a long time arguing that the rise of identity politics in the United States, particularly in the run-up to the 2016 election, is due to the fact that we no longer have “the possibility of old-fashioned ‘experience’ that is, perspectives and feelings that can be shared across group boundaries.” In his view, people have become alienated from each other, and as a result they believe that their own experiences—filtered through their individual identities—are now the only legitimate avenues toward status or success. But his explanation as to why “old-fashioned experience” is less available now (“social changes were deepened by modern communications technology and social media”) notably leaves out any critique of capitalism. While it may be true that Americans are alienated, Fukuyama fails to consider that the cause of this feeling might not be identity politics or smart phones or echo chambers, but rather the very neoliberal reforms Fukuyama himself advocated for, and from which he is only now stepping back. When an entire generation is handed a bill for a college they can’t afford and are stuck in a job with no upward mobility and told that none of them will retire and will probably die after all the cities are flooded in 40 years, you can expect that to alienate them more than some random person who happens to call gingerbread men “gingerbread people.”

This is by far one of the most frustrating things about reading Fukuyama in general—his idea that the market deregulation and the austerity that defined the 1980s just “happened,” and that no one in particular was responsible for it, or imagined what the consequences might be, or fought to prevent it. In an article he penned in 2011 for the American Interest, Fukuyama writes, “as the years went by and those outsized gains at the top of the income distribution pyramid failed to trickle down in any substantial way, one would have expected growing demand for a left-leaning politics that sought, if not to equalize outcomes, then at least to bound their inequality. That did not happen.” But it did happen! There were clear demonstrations against austerity in the 1980s. Take, for example, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) strike in 1981, where air traffic controllers went on strike seeking better working conditions and higher pay: in other words, left politics in action. The strike was declared illegal, and Reagan fired the 11,345 striking air traffic controllers. It’s not that there was no demand for left-leaning politics during the 1980s, it’s that left-leaning politics were vigorously suppressed and punished. It’s the old “why are you hitting yourself?” excuse.

By side-stepping material concerns altogether, Fukuyama misses the long-running material inequalities that underlie identity politics, and instead frames the conversation as one about national identity. This logic, for Fukuyama, applies not just within the U.S. but internationally: Just as identity politics in the U.S. is related to a weakening sense of national identity, so too is a lack of “national identity” the main source of instability in other countries. Only certain forms of “national identity” are acceptable, of course: As Fukuyama writes, “liberal democracy has its own culture, which must be held in higher esteem than cultures rejecting democracy’s values.” If you’re wondering which cultures reject “democracy’s values,” they’re the countries in the Middle East that the U.S. has invaded, but not the ones with whom we have important trade relations. Of the Middle East generally, he writes, “weak national identity has been a major problem in the greater Middle East, where Yemen and Libya have turned into failed states, and Afghanistan, Iraq and Somalia have suffered from internal insurgency and chaos.” Here, Fukuyama seems to be suggesting that if only places like Yemen and Libya had stronger national identities, they wouldn’t be in the midst of crisis. This ludicrously simplistic analysis completely glosses over the important historical and geopolitical reasons why these countries are in crisis. Perhaps the reason Yemen is not currently a delightful place to live has nothing to do with its sense of national identity, but a lot more to do with the fact that Saudi planes, with the help of the United States, bomb the country regularly. The material realities of the problems Yemenis are facing, and the main source of their alienation (e.g., starvation, disease, and war) are never touched upon throughout the book.

Of course, Identity isn’t even the first time that Fukuyama has pretended to make some kind of ideological shift which has then proved to be totally superficial. In February 2006, Fukuyama wrote a vague critique of the Iraq War in the New York Times, and then, not even a month later, served on the steering committee for the defense fund of Dick Cheney’s former Chief of Staff, Scooter Libby. (Let’s not forget that Libby leaked a CIA agent’s identity to the press because her husband wrote an article in the run-up to the Iraq War showing that Niger wasn’t selling uranium to Saddam Hussein.) Fukuyama isn’t the only neocon to have loud public changes of heart, only to quietly continue supporting the same people and policies as before. For example, Atlantic staff writer David Frum, who publicly denounces Donald Trump, espouses pretty much the same views on immigration now as he did in 2007, before Donald Trump’s ramping up of the brutality of ICE and CBP. Max Boot, another never-Trump conservative, made a splash at the end of 2018 with his book The Corrosion of Conservatism: Why I Left the Right, in which he argues that the conservative movement in America is now dominated by nativism, xenophobia, racism, and assaults on the rule of law. As tweets like this suggest, modern conservatism has none of the classy values of the past, such as genocide. Why do we keep handing out second chances to Fukuyama, or any of his neocon cohort, just because approximately every decade they spuriously claim to have abandoned their beliefs?

Identity does offer a semblance of support for center-left projects, which I fear might cause the book to appeal to a lot of people. Anand Giridharadas, whose own recent book Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World, which was critical of how the global elite use charity to preserve their own wealth and influence, wrote a positive review of Identity. “We need more thinkers as wise as […] Fukuyama,” he wrote, “digging their fingers into the soil of our predicament. And we need more readers reading what they harvest.” But remembering Fukuyama’s past can help us to see the chicanery in Identity masquerading as “wisdom.” In explaining how we can translate the abstract idea of “identity” into a political project, Fukuyama writes: “we can start by trying to counter the specific abuses that have driven assertions of identity, such as unwarranted police violence against minorities or sexual assault and sexual harassment in the workplaces, schools and other institutions.” This would seem to put him in at least the same camp as liberals, and perhaps in the same camp as socialists. However, these gestures towards social justice are immediately undercut by his strange, hostile caricatures of the left. He writes that in the last few decades “the left’s agenda shifted to culture: what needed to be smashed was not the current political order that exploited the working class, but the hegemony of Western culture and values that suppressed minorities at home and developing countries abroad.”

Fukuyama’s claim that “identity politics” is not a constituent piece of the class struggle against the current political order, but is in fact an abandonment of the class struggle in favor of an extravagant alternative project to destroy Western culture, is both deliberate and extremely underhanded. As a rhetorical move, it is little better than the language used by YouTube reactionaries who position the “cultural Marxism” of the universities as the foe of “Western culture.” Even if we interpret this as a good-faith critique rather than a conservative dog-whistle, Fukuyama is simply repeating the old canard: “the left used to be good, but now it’s too obsessed with identity.” Given that Fukuyama was historically an enemy of all the left’s social and economic projects, his rebrand as a defender of the good ol’ left against its modern perversions is as bewildering as it is rich. Fukuyama doesn’t even cite left wing authors while he advises the left on how to do politics, instead citing conservative French Canadian journalist Mathieu Bock-Cote’s book Multiculturalism as a Political Religion as his source on the dangers of sacrificing class for identity.

Many of the architects and mouthpieces of social alienation and massive wealth inequality successfully rehabilitated themselves after the 2016 election. For every neocon like Fukuyama, there’s a liberal “just war” cheerleader like Jonathan Chait, who previously supported the Iraq War and now regrets it—on the grounds that it was based on faulty intelligence and poorly executed, not because he acknowledges that killing half a million people is wrong. Chait has gone on to use his newfound credibility to attack the left over and over. When Elizabeth Warren, for example, voted against raising the cap on the number of charter schools in Massachusetts, a bill heavily supported by the charter school lobby in the state, Chait argued that this proved that Warren “would support the teachers union on any position, however harmful it might be to the well-being of low-income students.” Essentially, he argues that Warren is choosing the side of those big bad unions and their “special interests” (read: being paid a living wage) against the needs of low-income students. When the article was originally published, he failed to disclose that his wife works in charter school advocacy, a fact he revealed only after someone wrote a response to his article. Another “just war” cheerleader, the aptly-named Anne-Marie Slaughter, initially supported the Iraq War and later admitted that this position had been a mistake, but today, she still maintains that interventionism is good, even with Donald Trump in charge of the military. As Obama’s former State Department Director of Policy Planning, Slaughter still has the connections to get booked on NBC or give TED Talks, where she’ll occasionally posture for center-left policies like job security for pregnant women, paid family leave, and healthcare for children, using her platform to host conversations with people like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. While it remains theoretically possible that she’s genuinely changed, it’s more likely that, just like Fukuyama in Identity, Slaughter doesn’t really support the redistributive economics necessary to give these policies any impact (which would threaten established power). There’s a particular art right now to appropriating the language of material social justice—see Kamala Harris—while simultaneously signaling to the powerful that you have no intention whatsoever of disrupting their wealth. Should a centrist Democrat like Harris become president, anyone who successfully positions themselves as a safer, “serious” alternative to more radical leftist ideology has a good shot at a position in the administration. And then, once invested in a neoconservative or neoliberal government, it always becomes magically impossible to implement social democracy. The only practical policies, as we saw with Fukuyama in the Reagan administration and Slaughter in Obama’s, end up being hard-right policies, and compromises with the hard-right.

It’s important to distinguish the impact of remoras like Fukuyama, Chait, and Slaughter from aristocrats like the Bush family: Arguably, the remoras are more insidious and more dangerous. While it’s true that the Bushes have been dramatically rehabilitated since 2016 (with some even bringing them into the fold of the #Resistance), the ideological impact of figures like Fukuyama, Chait, and Slaughter is simply larger: As intellectuals and journalists, Fukuyama, Chait, and Slaughter receive speaking invitations and column inches all the time, whereas figures like George Bush make curated banal media appearances only occasionally. Only after 2006, when it was convenient and politically safe to do so, did Fukuyama, Chait, and Slaughter brand themselves as #Resistance Heroes of the Bush era, publicly and dramatically walking back their earlier support of the Iraq War. Their continued relevance in 2019 reveals just how short our collective memory is. None of their ideas are new: They’re just the same repackaged bile we’ve been spoon-fed for years, this time with a shiny social justice gloss.

The Chait, Slaughter, and Fukuyama types are reminiscent of Kichijiro, a character from Martin Scorsese’s 2016 film Silence. Based on the novel of the same name set during the isolationist Edo period, two Jesuit priests voyage to Japan to convert the Japanese to Catholicism, all while evading Japanese authorities and trying to protect the “hidden Christians” from being captured and killed by the main antagonist, “The Inquisitor.” Kichijiro, an alcoholic fisherman, pretends to support the priests’ mission until he betrays them to the Inquisitor. Over the course of the film, he does this several times, telling the priests to their faces that he supports their cause, and then betraying them behind their backs. Each time, he seems more and more distressed as he returns to the priests and begs for their forgiveness. And being the good Catholics they are, the priests always grant it to him. We do the same with people like Fukuyama, Chait, and Slaughter: They enable oppression, social alienation and war, and then claim to renounce those acts, only to go back to enabling oppression, social alienation and war a few years later, cloaking it in the updated language of genuine concern. However, unlike the Catholic priests of Silence, we don’t have to forgive them.