On March 30, 1999, a roller coaster known as “Apollo’s Chariot” had its first public demonstration at the Busch Gardens theme park in Williamsburg, Virginia. Busch Gardens Williamsburg is one of two Busch Gardens-branded parks in the United States, although neither park is operated by Anheuser-Busch anymore. Busch Gardens Williamsburg is Europe-themed, while its sister park in Tampa is Africa-themed and was formerly known as “Busch Gardens: The Dark Continent.” (Although less overtly racist, the Europe-themed park in Williamsburg did arguably disrespect Europeans by a) only selling Budweiser beers in its pretend pubs, and b) inexplicably including Canada as a European country with a themed district in the park.)

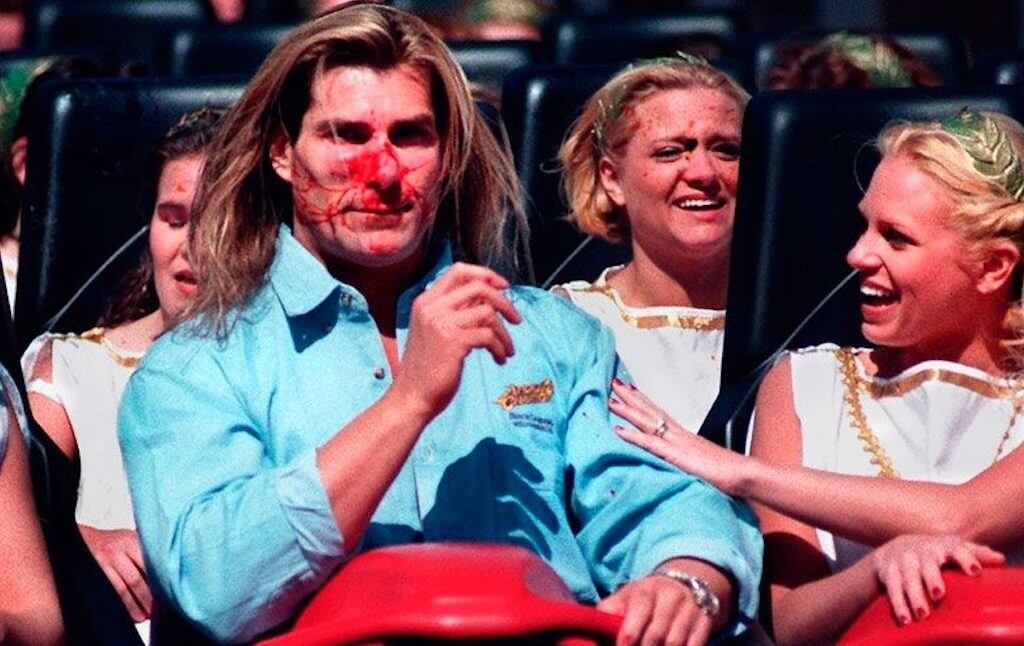

Apollo’s Chariot is a 73-mph steel coaster with an initial drop of 210 feet, located in the “Festa Italia” district of Busch Gardens, home to other Italy-themed rides like “Roman Rapids,” “Da Vinci’s Cradle,” and “Escape from Pompeii” (the latter of which has always struck me as an insanely disturbing premise for a ride, akin to “Escape the Twin Towers”). Amusement parks usually try to drum up publicity for a new coaster by enlisting a celebrity to participate in its inaugural public ride. For Apollo’s Chariot, Busch Gardens snagged Fabio, the shiny-abbed Italian model famous for gracing the covers of numerous 1980s romance novels. He boarded the coaster in a trademark half-open shirt, surrounded by a bevy of blonde girls dressed in togas and gold laurels, and the prospect of a pleasant, inoffensive photo-op seemed pretty much assured.

Unfortunately for Busch Gardens, a tragedy of Phaethonesque proportions soon unfolded. As the front car of the roller coaster was descending the first drop, a wayward goose collided with Fabio’s face. When the coaster rolled back into the station, Fabio’s nose was sliced open, his face spattered with blood, and the girls around him were all either grimacing or visibly cracking up. Busch Gardens immediately scrambled to do damage control, as Fabio took to morning news programs to warn the public about the dangers of Apollo’s Chariot. “It was not a freak accident, and it’s going to happen again,” he predicted darkly on Good Morning America. “A person—or even a child—can be killed.”

As it turned out, the public largely ignored Fabio’s premonition that Apollo’s Chariot would kill again, and it went on to become one of Busch Gardens’ major attractions. I rode it for the first time in early 2000 (although I then had to wait another year before I could ride it again, because the ride attendant caught me and realized I was under the required height restriction). Over the next ten years, I think I must have ridden it well over a hundred times. I still think it’s one of the best roller coasters around. It’s an incredibly smooth, thrilling ride, never jerky or nausea-inducing, with perfectly-timed drops. What makes it better still is the car design: many roller coasters have over-the-shoulder harnesses, or, if they use lap-bars only, have small enclosed cars that keep your feet trapped during the ride. But Apollo’s Chariot has an open car with only a triangular lap-restraint, meaning that you can swing both your arms and your legs with complete freedom throughout the ride. Depending on your size, you can also—with some stealthy maneuvering when the attendant comes around to check—position the lap restraint so that there’s a bit of a gap between your hips and the restraint, and that way you can actually feel your body rising up out of your seat when you descend a hill.

Sometimes people are surprised to learn how much I love roller coasters, because I am notoriously cowardly in other areas of life. I can’t watch even the most mildly frightening of scary movies. Recently, I tried to read Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, the plot of which is mostly “people feeling vaguely uneasy in badly-decorated rooms,” and found the damn thing so terrifying that I had to stop reading it before bed. For some people, roller coasters are fundamentally about the peculiar enjoyment of being afraid; one friend of mine told me that she rides roller coasters because she is a masochist, and another because it makes her feel courageous when she conquers her terror. But I don’t really think that’s why I like them at all. I’m not particularly afraid of roller coasters: despite Fabio’s statistically insane encounter with unlucky waterfowl, roller coasters generally have extremely low accident rates. As a Six Flags study points out (with a strident hint of doth-protest-too-muchness), “a [park] visitor has a one in one-and-a-half billion chance of being fatally injured and… the injury rates for children’s wagons, golf carts, and folding lawn chairs are higher than for amusement rides.” When I’m climbing the first big drop of a roller coaster, especially a familiar one, I feel a deep sense of calm: and when the drop finally comes, my conscious brain processes the surge of sensation in my belly exclusively as delight. But it would probably be wrong to say that there’s no risk-seeking element to my enjoyment, either. The visceral pleasure of speed feeds into a kind of weird, intense, happy contemplation of the annihilation of your physical body: the fleeting sensation of being an almost weightless entity, with only the pressure of a little foam triangle between you and a freefall into empty space.

The spiritual intensity of roller coasters has actually been the subject of an interesting (if morbid) thought experiment by a Lithuanian artist named Julijonas Urbonas, who in 2010 released a design for what he dubbed “the ultimate thrill ride”: the Euthanasia Coaster. A 510-meter steel coaster with an initial drop seguing into a series of increasingly-small loops, the Euthanasia Coaster is, according to Urbonas’ website, “a hypothetic death machine in the form of a roller coaster, engineered to humanely—with elegance and euphoria—take the life of a human being.” During the ride, passengers are “subjected to a series of intensive motion elements that induce various unique experiences: from euphoria to thrill, and from tunnel vision to loss of consciousness, and, eventually, death.” About seven times as tall and nearly three times as fast as the average amusement park roller coaster, the ride would be engineered to inflict lethal levels of G-force on its riders. Urbonas imagines the experience of riding the roller coaster as follows:

“You are slowly towed to the top of the drop-tower. It takes a while, as the ride is about half a kilometre long… You relax and press the FALL button… Gravitational choreography! The scooting gust of wind, goose bumps, suspension of breath, and vertigo—a set of experiences comprising a sort of fairground anesthesia—prepare you for the final part of the ride. Now you are already falling at a speed close to the terminal velocity, when the force of air drag becomes equal to the force of gravity, thus cancelling the acceleration. You feel your body as if supported by an air pillow. Just after this point, the track smoothly straightens forward, entering the first loop of the coaster, a continuously upward-sloping section of the track that eventually results in a complete 360-degree circle, completely inverting the riders at the topmost part. The centrifugal force drives the car upward, and you are literally pinned to the seat, your buttocks’ flesh pressed against the ergonomic planes of the seat so hard that your body is almost immobilized. … The rest of the ride, six or five loops, proceeds with your body being numb, ensuring that the trip ends your life. You die, or, more accurately, your brain dies of complete oxygen deprivation, a legal indicator of death in many jurisdictions. The biomonitoring suit checks if there is a need for a second round, which is extremely unlikely, as the result is guaranteed by a seven-fold repetition.”

Now, there are certainly some kinks to be worked out before this proposed death machine becomes operational: For example, the careful qualifier that brain death is a “legal indicator of death in many jurisdictions” makes it sound like there’s some ambiguity that the ride will actually kill you good and proper, and nobody wants to ride the Irreparable But Nonfatal Brain Damage Coaster. That said, my first thought on reading about the Euthanasia Coaster was: This sounds like an okay way to go out. For those of us who are scared to die in pain, but also rather scared to die in bed, what could be better than simply fainting away while hurtling through the air at 220 miles per hour? Your last conscious thought something between “I’m flying!” and “wow, my buttocks are pressed against a truly ergonomic seat”? It sounds a hell of a lot better than a hospital, anyway.

But apart from injecting some whimsy into the usually-grim debate surrounding euthanasia, are there any ethical implications to roller coasters—arguably an extravagant and expensive form of amusement in a world of great suffering? What is the correct left opinion on roller coasters? [1] The history of roller coasters, I regret to say, has a certain capitalist undercurrent, which isn’t surprising given that the only place you can find roller coasters nowadays are merchandise-laden amusement parks owned by gigantic corporations. Roller coaster construction has long been dominated by the rich, and most of us grew up believing that the proper people to design and build roller coasters were Tycoons. The earliest roller coaster prototypes—which were big slopes carved from ice and buttressed with wooden supports—were built by Russian aristocrats starting in the 18th century. [2] Word of these rides soon began to spread around Europe, and in the early 19th century, a company in France called “Les Montagnes Russes” began building wooden tracks with wheeled carts that were intended to emulate the Russian ice slopes. The first true “gravity ride” or roller coaster in the United States was the Coney Island “Switchback Railway,” designed and built in the 1880s by a wealthy businessman, LaMarcus Adna Thompson, who made his fortune in hosiery. (Thompson’s engineering design was inspired by the Mauch Chunk Switchback Railway, a coal-hauling railway in the Pennsylvania Mountains that had to navigate a number of steep inclines and drops, which began offering thrill rides to tourists once they realized that some peculiar people would actually pay to be thrown down a mountainside.) Thompson apparently chose Coney Island as the site of his attraction because he hoped to lure poor people away from the barrooms, brothels, and other such unsavory vices available in the same area. As he wrote: “Many of the evils of society, much of the vice and crime which we deplore come from the degrading nature of the amusements entered into. To inveigh against them avails little, but to substitute something better, something clean and wholesome and persuade men to choose it, is worthy of all endeavor… Sunshine that glows bright in the afterthought and scatters the darkness of the tenement for the price of a nickel or dime.”

There’s some intricate double-bluff charitable-rich-guy logic going on here, of course: Thompson knows that poor people will seek out “amusements” in response to the “darkness of the tenement,” but instead of trying to fix the whole darkness-of-the-tenement business, he instead proposes to offer poor people a more “wholesome” amusement, and gently implies that he is heroic for selling it to them on the cheap. But on the other hand, this style of conservatism is preferable to certain modern iterations, in that it at least acknowledges that non-wealthy people are allowed to have fun. Compare Thompson’s stance to that of the Washington Post columnist who flatly declared a few months ago that “If you’re in debt, you don’t deserve a vacation… I am not impressed that you saved for a summer trip to Walt Disney World with your children when you haven’t even set up a college fund.” If the Thompson position on roller coasters is something like “give them circuses, to distract them from the fact that they have no bread,” the Washington Post position is more like “you have no bread, and therefore deserve no circuses.”

“Equal access to roller coasters” is probably not the most important issue facing humanity at the moment, although at this point I am more confident that the Democratic Party will soon put out a thoughtful policy platform on roller coasters than a thoughtful policy platform on immigration. That said, roller coasters are probably one of the nicest human inventions ever made. I think Thompson was not entirely wrong when he articulated that roller coasters produce a truly unique form of enjoyment that doesn’t come bundled up with many physical or psychological downsides, and which sometimes is even capable of producing transcendent human emotions. I was lucky, as a kid, to live near an amusement park with very good rides, and that my family could afford the annual summer pass, so that getting to ride a roller coaster wasn’t a matter of scraping together money over many months, but simply a matter of deciding “would I like to go ride a roller coaster today?” More recently, I visited Six Flags Fiesta in San Antonio and rode a roller coaster for the first time in a number of years, and was shocked by how radically the experience improved my depressed mood.

And so, when I fantasize about the Utopian City of the Future—a popular topic of conversation here at Current Affairs—I always imagine that every modest municipality will have one really good roller coaster, open to the public. Why don’t cities have roller coasters, the way they have movie theaters and museums? Why do we keep our amusement paywalled inside private parks? It instinctively feels like an absurd and frivolous demand, and perhaps it is: maybe we will find out that in a world of fairly-apportioned resources, we do not have the raw materials and manpower hours left over to also build environmentally-responsible roller coasters. But who knows! Sure, rides aren’t especially cheap to build, but they are a lot less expensive than, say, a commercial skyscraper, and give rise to considerably more human happiness. Maybe once we figure out our national public transport system, roller coasters can be the next big public infrastructure project.

We will probably have to do something to protect the geese, though.

[1] True story: I googled “roller coasters socialism” to see if anyone had attempted to mandate a Left Position On Roller Coasters, but all that came up was a 1998 New York Times articled entitled “Socialism and its long lines are alive and well at Disneyland,” in which—I kid you not—a NYT columnist spends a day at Disneyland and attempts to demonstrate that his annoyance at having to wait his turn in line for rides is evidence that socialism is fundamentally flawed.

[2] Even today, the word for “roller coaster” in Spanish, and evidently in several other languages, is montaña rusa, or “Russian mountain.” Strangely, however, Wikipedia tells me that in Russian, roller coasters are called американские горки, or “American mountains.” Why is no one willing to take credit for something awesome?!