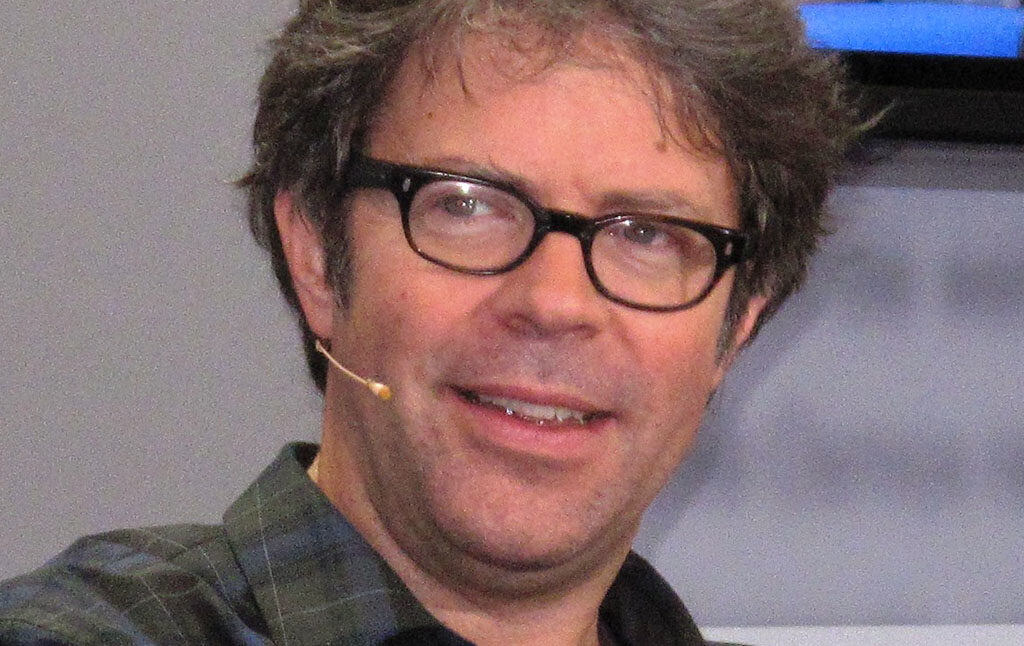

Franzen’s Privileged Climate Resignation Is Deadly And Useless

“We’re doomed so just garden and be nice” is neither scientifically valid nor morally acceptable…

Jonathan Franzen—the novelist best known for making everyone, even Oprah, very angry—has once again made everyone angry. On Sunday, Franzen published an article in the New Yorker arguing that climate change is unstoppable, and anyone who believes otherwise is fooling themselves. “The climate apocalypse is coming,” reads the opening text. “To prepare for it, we need to admit that we can’t prevent it.” He even compares progressive climate activists to climate deniers, arguing that it is as useless to fight for a different political system as it is to deny reality altogether. A fiction writer’s job is to imagine worlds and people that don’t exist and bring them to life on the page. Why is it easier for Franzen to fantasize about the end of the world than a Green New Deal?

Franzen justifies his beliefs with breathtaking arrogance, comparing his armchair philosophizing to the climate modeling work done by actual scientists on actual supercomputers:

As a non-scientist, I do my own kind of modelling. I run various future scenarios through my brain, apply the constraints of human psychology and political reality, take note of the relentless rise in global energy consumption (thus far, the carbon savings provided by renewable energy have been more than offset by consumer demand), and count the scenarios in which collective action averts catastrophe.

I regret to inform you that the results from Franzen’s “brain model” are grim—there simply is no way to avoid the climate apocalypse. This reminds me of the time I felt a lymph node in my neck, ran my own completely fact-free brain model, and concluded that there was a 100 percent chance I had neck cancer (probably the life-threatening kind). Like the nurse who told me I was full of it, plenty of educated folks on Twitter have pointed out the insanity of Franzen’s catastrophizing.

Let’s recap the state of the climate. Earth is about 1 degree Celsius warmer today than in the 19th century, with most of that warming happening since 1975. Wildfires in California are more common now in part because of climate change, and record-setting heat waves and rainfall have increased around the globe. We would like to limit global warming as much as possible, because dramatic changes can happen from what seem like small shifts in temperature—a drop of 5 degrees C triggered the last ice age. But changing course is hard. To keep warming below 1.5 C, which is the target of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, global greenhouse gas emissions will have to fall by about 45 percent by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050. Every bit of warming above that increases our risk of extreme weather and dangerous climate feedback loops, and even a world warmed by 1.5 C isn’t safe.

In short, Franzen is not wrong to be pessimistic about our future. Global emissions continue to rise, making the 2030 target feel wildly optimistic. Even the Paris Agreement’s more relaxed goal of limiting warming to 2 C seems unlikely at best. But Franzen is dangerously wrong to conclude that all climate mitigation is useless. For one thing, there is a very large difference between “unlikely with our current politics” and “physically impossible.” We cannot know if a 2 C target is impossible unless we try. Young activists like Greta Thunberg and the Sunrise Movement, who go unmentioned by Franzen, are redefining the terms of the climate fight and could very well do the unthinkable. The political possibilities for radical action on climate change are changing as organizers do the hard work of building a powerful social movement.

Franzen names several challenges to effective climate policy, but none of them are new. To stop climate change, he says that “overwhelming numbers of human beings, including millions of government-hating Americans, need to accept high taxes and severe curtailment of their familiar life styles without revolting.” Franzen, who probably has the French gilets jaunes protest movement in mind, is right to be worried about potential backlash to climate legislation. But every serious person working on climate change thinks about these issues constantly. The Green New Deal is designed to combine a jobs program and strong social safety net with an aggressive energy transition program, precisely in order to prevent this kind of reaction and make sure climate justice doesn’t conflict with economic justice. In fact, for all Franzen’s stereotypes of oil-loving Texans, the Green New Deal is very popular around the country. The main obstacle to climate action is not public opinion, but the entrenched interests intent on stopping it, the oil-and-gas companies with more to gain from resource extraction than a switch to carbon-free energy.

Franzen’s more dangerous argument rests on the premise that, after a certain warming threshold, the climate apocalypse is inevitable. Franzen claims baselessly that “it probably makes no difference how badly we overshoot two degrees,” because the whole system would fall apart. This is not true, and I have no idea how that claim made it past the New Yorker’s legendary fact-checking department. As actual climate scientist Kate Marvel points out, there is no magical point of temperature rise separating “apocalypse” from “not-apocalypse,” only a gradual slope of worsening futures. 3 degrees of warming is worse than 2, but it is much better than 4. (Embarrassingly, Dr. Marvel did not account for Franzen’s brain model in her calculations.)

Franzen has been full of environmental hot takes (no pun intended) for years now. In his 2010 novel Freedom, protagonist Walter Berglund is a lawyer and environmental activist who, like Franzen, adores birds. Walter wants to set aside a sanctuary in Appalachia to protect a rare species. After years of activism, Walter makes a devil’s bargain—he joins forces with a coal baron on a mountaintop removal mining project, intending to repurpose the destroyed landscape for his bird. In an interview with the Guardian, Franzen suggests that Walter’s choice is not unreasonable:

Walter comes to feel that coal is maybe not so bad. He sees that we aren’t going to stop using coal in this country, and he asks, “Why don’t we talk about how to do it better, how to do it right, rather than taking extreme positions that feel good but have no realistic alternative solutions to offer?” His position is not my position, exactly—I’m an agnostic on this stuff. But I don’t actually think it’s a crazy position to take.

Franzen sees Walter as a pragmatist, someone defending something concrete, real, and present by making compromises. But Walter’s actions rest on shaky ground. For one, what he believed was unchangeable did change: The U.S. has transitioned rapidly away from coal, burning less in 2018 than in 1979. More importantly, Walter’s concrete, real, and present bird does not exist in a vacuum. For example, if it drinks water from rivers poisoned by mining, it could die even in a protected sanctuary.

In his essay, Franzen sounds a lot like Walter. “Despite the outrageous fact that I’ll soon be dead forever, I live in the present, not the future,” he writes. “Given a choice between an alarming abstraction (death) and the reassuring evidence of my senses (breakfast!), my mind prefers to focus on the latter.” The implication is that climate change is like death—distant and certain and nebulous. But Franzen is wrong. Climate change is already concrete, real, and present. Maybe for him, safe in his comfortable organic gardens, climate change is a distant threat, but for people displaced by Hurricane Dorian and other disasters it is an immediate danger. Focusing on the present is a good idea. Perhaps Franzen should take his own advice and look at the changing world around him.

Franzen does eventually find a way to justify decreasing carbon emissions, but only by invoking some weird abstract ethical principles. “To fail to conserve a finite resource when conservation measures are available,” he writes, “to needlessly add carbon to the atmosphere when we know very well what carbon is doing to it, is simply wrong.” I have some sympathy with this view—I personally am a vegetarian, even though I know the meat I’m avoiding will have little impact on the global climate. But there is a stronger reason to decarbonize our global economy, one that any real climate model will tell you: Limiting greenhouse gases will limit climate change. I’m not sure why Franzen is unwilling to say that.

The true emptiness of Franzen’s view becomes apparent at the end of the article. Franzen has just argued that the apocalypse is inevitable. He believes that there is nothing we can do to stop runaway climate change, and that all the activists around the world are wasting their time. If he were consistent, Franzen would be building a bunker and loading up on gasoline and food for a Mad Max-type scenario. I would respect him more if he did.

But for all his doom and gloom, Franzen can only end with something even more saccharine than a Hallmark card. In the face of the inescapable apocalypse, Franzen argues that our actions somehow take on greater meaning. In his new moral framing, each of us have a duty to make small changes to strengthen our shared social fabric. In fact, he claims that “any movement toward a more just and civil society can now be considered a meaningful climate action.” As concrete examples, Franzen advocates for organic community farms, “kindness to neighbors,” and stopping “the hate machines on social media.” My mind is probably too small to comprehend Franzen’s brain model, but I fail to understand how being nice on Twitter is somehow a more practical or hopeful climate solution than a Green New Deal. It may be convenient to re-conceptualize neighborliness and plant-tending as “meaningful climate action,” because it means you don’t have to expend any real effort or give up any comfort. But it’s far more meaningful to take concrete political action that will save human lives. Franzen poses the question “What if we stopped pretending we’re doomed?” But the climate activists pose a series of better questions: “What if we refuse to accept doom as inevitable? What then will we have to do? And how do we plan to get it done?”