Cancelling Student Debt Reduces the Racial Wealth Gap

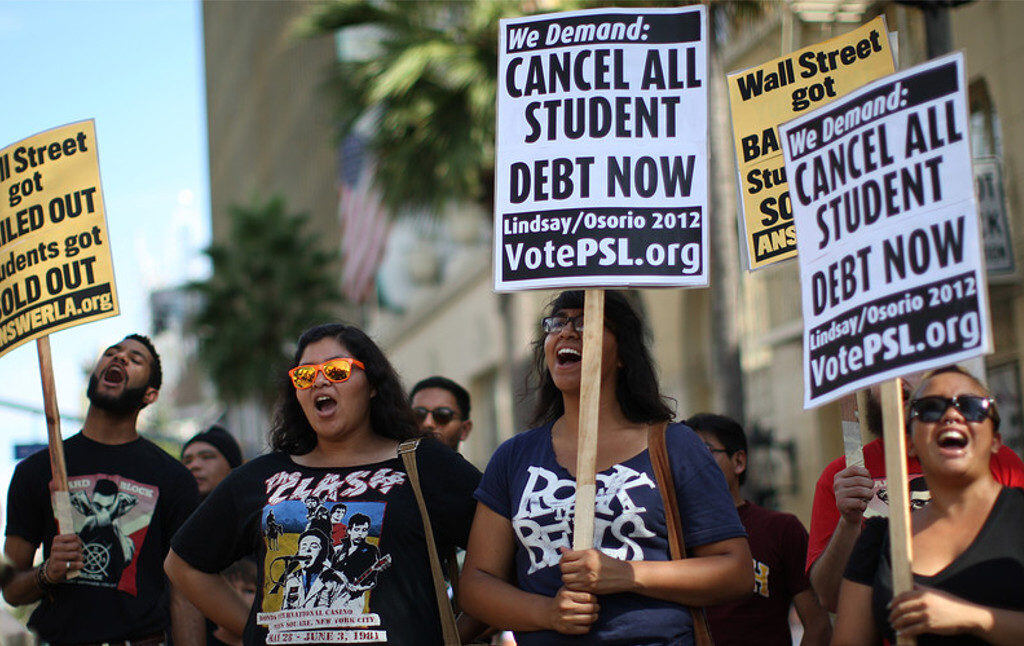

Debt cancellation must be on any progressive agenda and we should be suspicious of anyone who calls it “regressive”…

Since Elizabeth Warren proposed sweeping student debt cancellation in April, and Bernie Sanders put forth his own more extensive plan in June, members of the D.C. establishment have invented all sorts of reasons why cancelling student debt is privileged, actually. “[It’s] a big gift to a select group of people” opined Sandy Baum of the Urban Institute. Jason Delisle of the American Enterprise Institute said Elizabeth Warren’s plan suffers from a “fairness problem” because it “favors one class of students over those who never took out student loans.” And last fall, New York Times op-ed columnist David Leonhardt asserted that most student debtors are “doing just fine.”

Student debt cancellation, however, is progressive, not regressive; rather than favoring one elite class of people over another, it would in fact benefit the poorest. Lower-wealth households are likelier to have student debt, and even more so if they’re Black. As such, student debt cancellation would also help close racial wealth gaps.

Why are Black households more likely to have student debt? The fault lies partly with a higher education policy that has emphasized filling the labor market’s supposed “skills gap.” This has resulted in credentialization—ever-increasing degree requirements to do the same jobs—which has served to diminish the labor market value of those degrees purchased with student debt. As degrees have become increasingly worthless, many people have gone back to school, taking on more degrees and therefore more debt. And since Black students have less family wealth and face more discrimination in labor markets to begin with, the harm done by credentialization falls disproportionately on them.

But if cancelling student debt obviously and directly leads to closing racial wealth gaps, how did the narrative about student debt cancellation and racial wealth inequality go so far off the rails? How did we end up with elite higher-ed policy wonks and newspaper columnists describing the beneficiaries of student debt cancellation as affluent, privileged, and/or undeserving? It has to do with the same reason the federal student loan program was expanded so much in the first place: the ideology of “human capital” and its ghastly failson, the “skills gap.”

The “human capital” theory starts like this: The value of labor is connected to what that labor produces. If you can produce things of high value, but you’re not getting paid an amount that reflects that high value, you’ll go produce value for someone who will pay you more. Through competition between employers, wages should supposedly approximate the “value” of labor as measured by what that labor produces. And the value of an individual’s labor—again, linked to the value of what they can produce—is their own personal human capital. If you learn new and valuable skills, you therefore increase your “human capital.”

We didn’t always view education this way. During the first half of the 20th century, the public high school movement spread the idea that education is a public good. Starting on a state and local level, proliferating free and open public high schools drove up enrollment and graduation. In the postwar era, and with a good deal of federal help, many state (and some municipal) governments extended this idea to higher education, offering free or very inexpensive college programs with the idea of eventually achieving universal enrollment for all who wanted it and could meet basic standards. But, starting in the late 1960s, Congress, the Department of Education, and eventually many state governments decided to stop treating higher education as a public good. Instead, it was reimagined as a mechanism by which students acquire the skills necessary to increase their earnings in the labor market, which is to say, their human capital.

If education is just about increasing students’ personal human capital, rather than a public good in its own right, then major public investment in the upfront cost of public higher education seems less necessary. It seems reasonable, in fact, that the students themselves should be the ones to pay for their own education. Financing the upfront investment in human capital has become the central concern of higher education policy; at 18 years old, the majority of potential students do not yet have the income or assets required to pay for an investment in developing their skills. Only after graduating and obtaining well-paying jobs, hopefully using their new skills, would they be able to pay. Student debt is the solution to that problem: borrow the money upfront; repay it later when you’re able. Since private lenders rarely make loans on reasonable terms without security to borrowers with no credit history, the government’s role is to guarantee the students so they can access the capital market—but nothing more.

In the 1990s, economists Kevin Murphy and Lawrence Katz theorized that the rising inequality they were starting to notice could be attributed to the skills gap between those with college degrees—“knowledge workers”—and those without. The solution to combating rising inequality seemed obvious: Make everyone a knowledge worker by giving everyone access to college. But certainly don’t just build more colleges and make them free for students. This would be too generous, violate then-ascendant austerian politics, and forego an opportunity for the financial sector to take its cut. Human capital theory had the better idea: Make sure everyone takes on student debt to pay for the “skills” themselves.

The plan backfired. Instead of creating a more skilled labor force, the United States shifted the cost of job training from institutions, states, and employers onto individuals who would never have taken on student debt in the past (because they would have entered the labor market without higher education or without debt, since the then-lower costs of college would have allowed them a degree without the need for multi-decade indentured servitude.) To the surprise of those who believe in human capital theory, more degrees have not resulted in higher earnings. Instead, earnings for people with college degrees have stayed relatively flat, while earnings for people without college degrees have dive-bombed, forcing students and younger workers to take on virtually any debt burden to avoid destitution. This, in turn, has given colleges enormous pricing power, which they have exercised to charge absurdly high tuition. Matters have gotten so bad that even a year of community college can cost a cool $10,000.

What is incredible in all this is that the skills gap is the least helpful way to think about rising inequality. It posits that well-paid workers are well-paid because they possess the scarce skills that bosses need. If that were true, then earnings for such skilled workers should have increased, but they have not. Instead, earnings for unskilled workers have decreased, and what counts as a “skilled worker” in terms of education credentials has spiraled further and further out of reach. The basic assumption here—that individual skills determine earnings—is now considered by labor economists to be false.

The skills gap neither explains why rich people are rich and everyone else isn’t, nor does it provide a policy prescription likely to solve inequality. Yet the false premise lives on, along with the new tragedy that it created: a large disadvantaged population unable to pay off its student debt. This population was something the skills gap theory failed to predict: It assumed that taking on student debt in exchange for more educational credentials would itself cause higher earnings that would then be applied to pay down the student debt.

In the face of widespread student loan delinquency and default rates, and a radical rise in enrollment into federal Income-Based Repayment programs, the reasonable response would be to reassess the skills gap theory and to question its power in shaping higher education policy. But these are not reasonable times and experts hate to be wrong. The reaction from the right and the center of the political spectrum has been to double-down on blaming the victim: They must have majored in the wrong thing, or dallied in graduate school when a smarter, savvier student would have come away with a more “marketable” credential.

What the skills gap mythology does explain, however, is why higher education policy elites are aghast at the idea of cancelling student debt. Their view is that having student debt must have given you skills and therefore made you rich, which means that cancelling student debt benefits rich people. They justify this assumption by pointing to borrowers with the highest balances, who do tend to have higher incomes. But presuming that student debt makes people rich is a significant misinterpretation of this fact pattern. In reality, the more wealth you have, the less likely you are to take out student loans—not surprisingly, since you don’t need them to pay for college.

The reality is that most currently-outstanding student debt is held by low-wealth, younger borrowers from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds. Specifically, Black people have more student debt than white people (controlling for income, wealth, and education). This is in part because the credentialization dynamic, as discussed above, is pernicious for non-white students and workers in particular. Discriminatory labor markets mean white graduates with a B.A. are more likely to be able to get a good job and start paying down their debt, whereas Black students might well need to go back for another degree, and yet more debt, to land the same job. This dynamic plays out against a background of enormous racial wealth gaps in family background that mean white people can get through higher education with much less debt than their non-white peers. Plus, segregation in higher education means that white students have access to better-resourced institutions which are less reliant on squeezing everything they can out of their own students.

If you’d like additional proof that cancelling student debt will help reduce the racial wealth gap, check out my new Jain Family Institute working paper. I found that the racial wealth gap would be reduced for all parts of the wealth distribution, but the reduction is most significant for the middle and the bottom. The Sanders plan to eliminate all student debt would do more to close the racial wealth gap than the Warren plan, because Warren’s plan is capped at $50,000, and lower-wealth households with more debt than that are disproportionately Black.

Why does student debt cancellation reduce racial wealth inequality in the middle and the bottom much more than at the top? Membership in the top wealth percentiles is highly racialized: There are very few Black people in the top 1 or even 10 percent. Importantly, though, student debt is a relatively insignificant component of household financial wellbeing for older and richer households, including 1-percent households. So it makes sense that student debt cancellation would make a smaller difference for the richest among us.

Since the paper was released, the sociologist Louise Seamster responded by pointing out the distinction between relative wealth gaps (as measured by wealth ratios), and absolute gaps (as measured by the difference in wealth levels between Black households and white households.) She rightly says that a given cancellation regime can increase the dollar gap between white and Black households while also reducing the wealth ratio. For example, suppose that the median white household has $100,000 of wealth and the median Black household has $10,000—a 10:1 ratio, and an absolute gap of $90,000. Cancelling student debt might increase the median Black household wealth to $15,000, while the median white household would have $120,000: a smaller 8:1 ratio, but a larger absolute gap of $105,000.

This, she argues, would seem to bring us further from an overall redistributive goal of reducing racial wealth inequality. Seamster further appeals to the historical point made by the sociologist and critical race theorist Derrick Bell about “interest convergence.” The idea is that political progress toward absolute gains for racial minorities often require “compensating,” or even over-compensating, the white population with material benefits of their own. This, Bell argued, serves to exacerbate the historical disadvantage that required intervention in the first place. Similarly, Seamster worries that cancelling student debt in a way that would cause white people to benefit just as much as disadvantaged populations of color—if not more—could reinforce this perverse dynamic.

It’s worth considering the implications of the important dynamics that Seamster points out. Absolute wealth gaps get larger the higher up the wealth distribution you go. The difference between a white household in the top 1 percent of white households and a Black household in the top 1 percent of Black households is much greater than the difference between a white and Black household at the median or near the bottom of the wealth distribution. Here is what it looks like in practice. Among households earning at least $1,000 a year, the richest 1 percent of white households have wealth of $32.5 million. The top 1 percent of Black households, by contrast, have $5.6 million. That’s a difference of $26.8 million. This difference alone accounts for 36 percent of the overall racial wealth gap. The wealth difference between the second-richest percentile of white and Black households accounts for a further 11 percent of the total racial wealth gap.

Meanwhile, the median white household possesses $159,000 of wealth, while the median Black household has $15,000. This is a large and shameful gap, but it is literally orders of magnitude less than the gap at the top. The bottom 20 percent of white households have $12,600. By comparison, the bottom 20 percent of Black households have nothing. If you were to take the bottom 50 percent of white and Black households, respectively, the wealth difference would account for a mere 3.1 percent of the overall racial wealth gap. In other words, if we measure the racial wealth gap in absolute terms, the racial wealth gaps between middle and working class white and Black households barely register as a portion of the overall racial wealth gap, and student debt matters even less. The racial wealth gap is largely a story about exactly how much wealth rich people have, and the fact that almost all, if not quite all of them, are white.

Student debt cancellation would reduce racial wealth disparities that matter a great deal to people in the broad middle of the wealth distribution, which are the majority of households in this country. But if we actually want to close the racial wealth gap, measured in absolute dollars, the solution is progressive taxation. Taxing the income and wealth of the top 1 percent, to the point that it’s illegal to have as much income or wealth as they currently do, is the most powerful tool we have for achieving racial equality in this country, just as it’s the most powerful tool we have for achieving equality of any kind. There’s a reason the atavistic and reactionary political movement known as conservatism has made regressive tax cuts its sine qua non of public policy for decades now. Student debt cancellation needs to be on any progressive agenda and we ought to be suspicious of any ostensible friend of the left whose campaign platform hems and haws around this crucial policy and whines (ignorantly) about its ostensible regressivity. But if eliminating racial wealth inequality is the explicit goal, then progressive taxation may be the best means by which that goal can ever be accomplished.