Estimates vary, but somewhere between one in three and one in four American women will, at some point in their lives, get an abortion. Access to legal abortion is, of course, already burdensome, largely dependent on location, wealth, social support, and the ability to get time off from work. With legal abortion in grave danger as state after state passes heavy restrictions or near-absolute bans, and the fate of Roe v. Wade likely to be decided by the kindness of Brett Kavanaugh, it’s more important now than ever for the Democratic Party to stand resolute on abortion rights. However, if you look at the behavior of many centrist Democratic politicians and media outlets, you’ll probably conclude that, as with most critical left issues, centrist Democrats don’t actually give a shit and aren’t committed to the cause.

In fact, what we get from centrist Democrats is often useless handwringing and concern-trolling. “My heart breaks for this ‘heartbeat’ bill,” said Nancy Pelosi, in reference to the law passed in Ohio that bans abortion at the point when a particular clump of cells expresses electrical impulses, colloquially and inacurrately referred to as a fetal “heartbeat.” In the same interview, “Pelosi called abortion a ‘tragedy,’ saying she respects the position of those who oppose abortion, including members of her own Catholic Italian family.” Two years ago, Pelosi cited those same anti-abortion relatives when she stated that abortion rights could not be a litmus test for Democrats. Focusing on reproductive justice, she warned, meant that liberals were guaranteed to lose:

[Pelosi] also suggested that the party’s presumed rigidity on social issues is one reason that Democrats were unable to appeal to segments of the electorate that might otherwise have been in tune with their broader agenda. “You know what? That’s why Donald Trump is president of the United States — the evangelicals and the Catholics, anti-marriage equality, anti-choice. That’s how he got to be president,” she said. “Everything was trumped, literally and figuratively by that.”

Here Pelosi directly blames LGBT people and abortion advocates for Trump’s victory, and yet liberals didn’t condemn her for it. In fact, they saved their ire for Bernie Sanders when he supported Heath Mello’s candidacy for mayor of Omaha. (Mello had previously voted for anti-choice legislation but vowed not to pass similar legislation as mayor; since he lost the election, it’s impossible to know whether he would have kept his word.) What is treason from a socialist is hard-headed practical realism from a centrist; it’s simply good politics when Pelosi casts abortion as a fringe issue, separate from the broader agenda of the party. It may break your heart, but there’s simply no moving people who disagree with you.

But how many people are really against abortion in the first place? In the Cut, Eric Levitz notes that “there is not a single state in the union where a majority of voters support ‘making abortion illegal in all circumstances.’” And according to the General Social Survey (GSS), 62 percent of Democratic voters now support complete access to abortion on demand no matter the reason. This is a remarkable uptick of 10 percent from two years prior. Yet the New York Times, reporting on this same data from the GSS, warned that “40 percent of Democrats say they oppose legal abortion if the woman wants one for any reason.” This misleading phrasing makes it sound like a full 40 percent of Democratic voters are totally against abortion, when in fact 38 percent (not 40) are opposed only to abortion on demand—i.e., they believe there should be at least some restrictions on abortion, but don’t necessarily oppose all abortion access. This New York Times report was titled “Politicians Draw Clear Lines on Abortion. Their Parties Are Not So Unified” and the subhead glumly advised readers: “It’s one of the most polarizing issues in America, and a political litmus test. But surveys find many voters struggle with its ethical and moral perplexities.” The New York Times could just as easily have trumpeted the swift and extroardinary rise in support for abortion on demand, so why this gloomy framing?

The Times is not alone; a recent article in the Washington Post bemoaned the increased ferver of abortion advocacy among Democrats. “‘We’ve become so intolerant,’ [anti-abortion] former congressman Bart Stupak (D-Mich.) said… ‘[The Democratic party] take[s] our money, but they can’t come to our events or help us out in our campaigns.’” Stupak, now an employee of Venable LLP who “lobbies on health-care issues,” decries the “almost vengeful” behavior of pro-choice advocates who criticized Joe Biden for supporting the Hyde amendment (a hideous piece of legislation which bans federal funding for abortion, meaning women on Medicaid must pay for their abortions out of pocket). Abortion advocates, like angry Furies, have destroyed the discourse: As Stupak went on to lament, “It just seems like we’ve lost a sense of civility.” It’s important to remember, as abortion rights are stripped away nationwide, first from poor women and then from everyone else, the true victim is…civility.

Why the Democrats are so afraid to stake out popular positions (and, in general, so afraid of power and addicted to losing) is a broader question for another day; but abortion, like so many issues, is a battlefield upon which the Democrats have always been too timid to mount a proper defense. Time after time, they have preferred to let their opponents set the field and dictate terms. As feminists have pointed out ad nauseum, exceptions for rape or incest make no sense if you believe life begins at conception, and if you believe life begins at conception, surely you must support maternal health care and the well-being of children post-birth. The vast majority of anti-abortion advocates are opposed to universal health care and family subsidies; this is because they are dishonest people who do not really care about children at all. At the same time, there are indeed principled Catholics and others who are genuinely troubled by the metaphysical status of the unborn, and for them, we recommend socialism. As an earlier Current Affairs article noted, socialism will naturally reduce abortion by eliminating poverty and improving healthcare, ensuring that people can afford to choose to have children if they want to. But for the most part, the statement “life begins at conception” is used to obscure the true anti-abortion argument, which is this: People with uteruses, by the nature of their biology, have too much control over the means of reproduction; these people are primarily women; and women cannot be permitted to possess authority that men lack, or the whole patriarchal edifice might disintegrate.

Due to its implicit threat to patriarchal power, abortion has become a convenient rallying point for the religious right. It wasn’t always their favorite villain; as Randall Balmer pointed out in Politico, abortion was once considered by evangelicals to be perfectly acceptable and a mere Catholic neurosis, but after the defeat of school segregation in the courts, leaders of the religious right realized that abortion had the appropriate ontological characteristics to be rebranded as a new cause célèbre. The evangelical pro-life movement is, and has always been, a marketing campaign for the religious right. It’s their top-selling vehicle for political power.

The battle against abortion is, as a whole, a relatively recent one; for most of human life on Earth, abortion fell within the accepted sphere of women’s power and influence. Women in most civilizations controlled reproduction; birth usually took place at home, and attended only by women. Obstetric forceps were invented in 1588, and the field of obstetrics muscled into the world throughout the next few hundred years. Male physicians duked it out with midwives (who were all too frequently accused of witchcraft), while the plunder and colonization of America offered a new front for the fledgling male medical profession to organize. In 1857, a mere 10 years after its founding, the American Medical Association began the fight to criminalize abortion in the New World. Leslie Reagan, who wrote “When Abortion Was A Crime” (basically the book on abortion) calls the AMA’s campaign “antifeminist at its core.” Criminalizing abortion was a direct strike against midwives and homeopaths, as well as women fighting for admittance to medical schools.

While male doctors organized for control over abortion, pregnancy, and gynecological care, they also relegated it to “specialized care.” For thousands of years, laywomen had carried institutional knowledge about human reproduction. But to male physicians, male bodies were frequently designated as the “default” while women were “special cases” whose reproductive organs guided and controlled most of their biology. In the West, women’s reproductive health was an area of morbid fascination for millennia; nearly every illness in women could be attributed to a wandering womb or some other damaging influence of the lady humors, a belief that lingered well into the 20th century. Since the reproductive system was itself pathologized as a source of disease, it needed to be controlled for the sake of women’s physical and mental health—and, incidentally, for the sake of continued patriarchal dominance. This has led to significant problems, of course, but the advent of actual scientific rigor in the medical profession (long after the founding of the AMA) has also meant important medical advances. In Doing Harm: The Truth About How Bad Medicine and Lazy Science Leave Women Dismissed, Misdiagnosed, and Sick, Maya Dusenbery lays out the contradictions inherent to contemporary women’s reproductive health:

The fact that women have become largely dependent on a male-dominated medical system for the ability to prevent, end, and safely bring to term a pregnancy—a freedom that’s so fundamental to women’s equality—has led to some tensions, to say the least. Undoubtedly, women have benefited in many ways from this medicalization of their reproductive lives; it’s given us more effective birth control, safer abortions, and lifesaving interventions in complicated pregnancies. On the flip side, women have had to constantly fight on a variety of fronts to maintain control: to simultaneously push for greater access, resist overmedicalization, and defend their autonomy in making reproductive decisions.

Where women’s liberation and the medical establishment have clashed since the founding of the AMA, it’s been a new struggle for old power. The collective authors of Our Bodies, Ourselves (1970) were a dozen women aged 23 to 39 who met at a women’s liberation conference in the Boston area. The initial “Women and their Bodies” workshop they attended was so provocative that they formed a group and set about researching topics: anatomy, sexuality, birth control, venereal disease, abortion, childbirth, and postpartum health. Their $0.75 “course handbook” attempted to wrest institutional knowledge back from a medical establishment dominated by wealthy white men. As the authors wrote in “Women, Medicine, and Capitalism, an Introductory Essay”:

We as women are redefining competence: a doctor who behaves in a male chauvinist way is not competent, even if he has medical skills. We have decided that health can no longer be defined by an elite group of white, upper middle class men. It must be defined by us, the women who need the most health care, in a way that meets the needs of all our sisters and brothers.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s there were other radical attempts to take power back from the male-dominated medical establishment. One of the most famous is Jane, formally known as the Abortion Counseling Service, a women’s collective that operated in Chicago from 1969 to 1973. About 100 women passed through the Jane collective as counselors over the years, but never more than a few dozen at a time; the group collectively facilitated approximately 11,000 abortions, initially coordinating appointments with friendly doctors, and eventually, after training, performing abortions themselves. In the fall and winter of 1972, the group offered a free post-abortion checkup with one of these friendly doctors, who reported that the service’s complication rate was roughly equivalent to that of New York’s legal clinics (between three and six per 1,000 D&C abortions). The collective was highly successful—until 1973, when Roe v. Wade was decided, and Jane dissolved. Control over abortion passed back into the hands of (mostly male) doctors. Roe v. Wade, which enshrined abortion as part of the right to privacy between a woman and her (again, usually male) doctor, wasn’t even close to the result that radical feminists wanted. Laura Kaplan—a former member of Jane—explains this in her book The Story of Jane: The Legendary Underground Feminist Abortion Service:

When New York’s legislature debated legalizing abortion in 1969 and 1970, radical feminists passed out a copy of their ideal abortion law–a blank sheet of paper. They advocated repeal and repeal meant no laws on abortion. They argued that any reform, no matter how liberal, was a defeat since it maintained the State’s right to legislate control over women’s bodies. With that control codified, as in New York’s liberal law, the door was open for further restrictions. These radicals could foresee a time when abortion was legal but relatively inaccessible, perhaps as inaccessible to most women as it had been before reform.

Their prophecy was correct: While abortion is technically still legal as of the time of this writing, it has become increasingly inaccessible. A 2016 Guttmacher Institute report shows the incredible multiplication of abortion restrictions: an average of 38 new restrictions a year in the 10 years following Roe, an average of 14 per year in the 28 years after that, and then, in just the five years between 2010-2015, another 288, a stunning 57 restrictions per year. According to another Guttmacher report from 2019, 24 states have laws regulating abortion providers beyond anything that can be remotely considered medically necessary. Roe, just as the radical feminists warned, kept power over women’s bodies in the hands of the state, and ultimately placed too much trust in the benevolence and stability of institutions. It’s a concession, a compromise, and a bad legal ruling. As Lillian Cicerchia writes in Jacobin: “Roe guaranteed privacy, not access. It guaranteed choices, not good choices. It (formally) guaranteed the right not to have children, not the right to have children in a safe and supportive environment. Roe gave pregnant people rights, not agency.”

This framing of abortion as a narrowly defined and easily-abridged legal right controlled by the state completely negates the autonomy that most people desire to exercise when it comes to their own bodies. That is, what we want is a positive, natural right, not given by the state but understood by everyone, like the right to breathe. And yet, in the public discourse, abortion has become a matter of private experience and guilt rather than a collective reality. As Yasmin Nair and Eugenia Williamson argue in the Baffler, “the left has failed to translate the experience of being denied rights to abortion into political and economic terms that affect everyone–even the anti-abortionists to whom they’ve ceded their authority on the matter. In casting abortion as something that should cause guilt, the left has forfeited any way to demand rights as rights.” If we accept the framing that reproductive control is a private sinful, guilt-inducing behavior that requires legalization, rather than a natural social freedom, then the left loses its greatest leverage: Abortions are common, and the right to abortion has always maintained relative popularity. (Discussing their campaign to criminalize abortion at the 1860 Annual Meeting of the American Medical Association, the president of the AMA declared: “It is difficult for legislation in a free country, where the people are the source of all political power, to rise higher than popular sentiment and intelligence.”) The only way to lose is to treat abortion as something shameful and “a complex issue” in need of state intervention and complicated trimester restrictions, rather than what it is: part of the suite of women’s reproductive options which are essential to our full freedom.

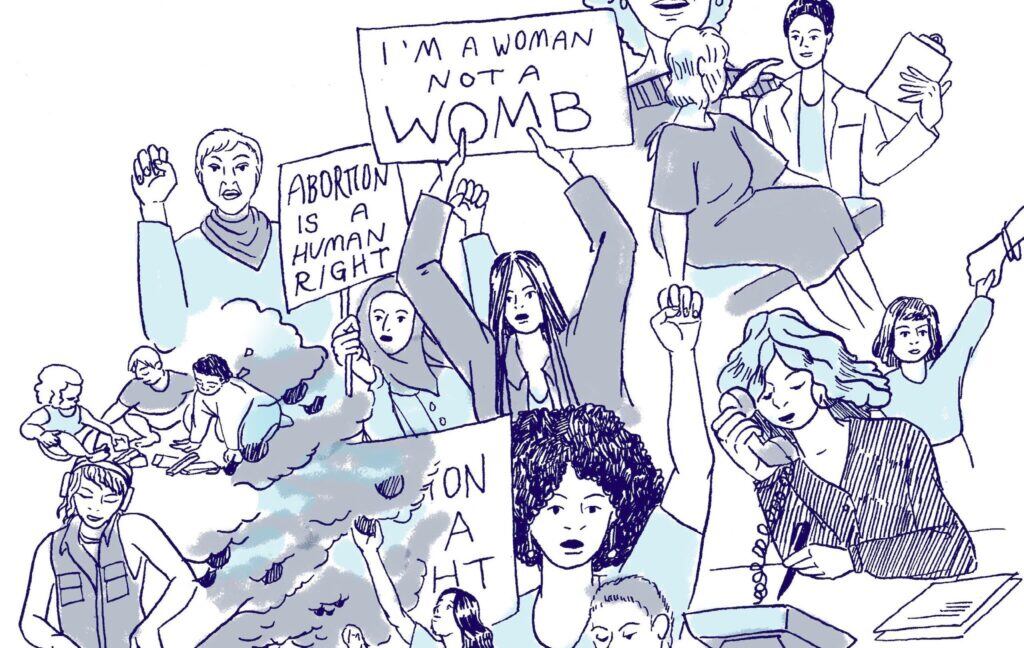

The left has lost so much ground since Roe. In this compromised position—where a woman is still dependent on the medical establishment for abortions, and with a technical guaranteed right but without guaranteed access—the left needs to reassert universal protections for reproductive justice in every level of government and popular life, a vision that by definition requires a mass movement of organized actors fighting for collective power.

In No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the Gilded Age, Jane McAlevey evaluates three common ways of achieving social change: advocacy, mobilizing, and organizing. She defines the “advocacy model” as a method of struggle which does not require collective action, but relies instead on paid lobbyists, PR professionals, media, lawyers, and other actors working with capital instead of popular, collective demand. “Mobilizing” requires turning out large numbers of already-committed activists to engage in crucial fights. “Organizing,” the strongest and most enduring, requires base building through recruitment of people who have never before been involved in the fight. McAlevey argues that while advocacy and mobilizing models can achieve occasional and moderate victories, truly radical, systemic social change can only be achieved through organizing.

For too long, defenders of abortion rights have relied on the advocacy model, with occasional whirlwinds of mobilizing. This is inevitable as long as Roe is the centerpiece of abortion rights. In a different piece for Jacobin, “What Medicare for All Means for Abortion Rights,” Cicerchia frames the problem with the current advocacy and mobilizing models:

…with Roe on the chopping block, liberal organizations are still clinging to the strategy which brought them to this conjuncture. They seek to preserve the tenuous legality of abortion under Roe, rather than entrenching it as a right within the healthcare system. In this way, the procedure has become technically permissible but far from accessible. Now, it’s in danger of becoming neither.

Medicare for All is the de facto universalist demand to address this need. It provides the capacity-building, maximalist, collective struggle to cohere change. But Cicerchia points out, “there is a temptation on the Left to overstate Medicare for All’s power to win greater abortion rights by itself. In this perspective, Medicare for All’s unifying power will simply transfer to its specific provisions for reproductive health funding. Emphasizing those provisions, on the other hand, could invite divisions within its potential base.” That is to say, we will still face challenges from anti-abortion advocates if women’s reproductive health care is treated within Medicare for All as a separable, special consideration rather than a natural human bodily process, experienced by a full 50 percent of the human population.

The left must not defend only “abortion rights,” using the advocacy and mobilizing models. The path to victory is an organized, universalist demand for bodily autonomy, including the right to healthcare. Even before the Hyde Amendment passed in 1976, the legalization of abortion did nothing to build expansion of healthcare access or to transfer social and economic power over reproduction back to women. The older feminist collective model may have held better answers. Kaplan tells us in The Story of Jane:

As members of the women’s liberation movement, the women in Jane viewed reproductive control as fundamental to women’s freedom. The power to act had to be in the hands of each woman. Her decision about an abortion needed to be underscored as an active choice about her life. And, since Jane wanted every woman to understand that in seeking an abortion she was taking control of her life, she had to feel in control of her abortion. Group members realized that the only way she could control her abortion was if they, Jane, controlled the entire process. The group concluded that women who cared about abortion should be the ones performing abortions.

As Dusenberry notes above, the long medicalization of reproductive health yielded some victories: better birth control, safer abortions, and better outcomes for complicated pregnancies, and basic best practices such as sterilizing instruments and washing hands. It isn’t necessary for every abortion to be perfomed by a loving supportive feminist collective, which may not be exactly easy to create in every part of the country. But moving the framework of abortion away from “a choice between a woman and her doctor” and towards simply being “a common part of reproductive life,” much like childbirth or menstruation, is essential. Publicizing the frequency and banality of abortion (as in the “Shout Your Abortion” campaign) is a decent start; creating abortion funds is another.

But simply talking about and funding abortions, as the patchwork of laws shift and abortion becomes more legal in one state, less in another, won’t solve the fundamental problem: Women’s reproductive rights are still viewed as distinct, sacrificable, and less important. They’re a special issue for a special population: a red state problem and (sometimes) a blue state privilege. In those same red states, mothers generally have higher maternal mortality rates, while the United States’ general statistics for maternal health are piss-poor, especially when the gap between outcomes for Black mothers is considered. This is where more holistic “abortion” funds can be valuable. The Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund is part of the NNAF (National Network for Abortion Funds), but it’s not just an abortion fund. Founder Laurie Bertram Roberts also provides support to parents and for basic needs. According to her:

Many people in Jackson [Mississippi] will not say the word “abortion” in public. They prefer euphemisms, like “taking care of a problem” or “women’s health care”; even in their own homes, they lower their voices before uttering the word itself. Roberts has responded to this secrecy with a bullhorn. She openly helps people obtain abortions. She takes them to dinner afterward. She provides them with whatever else she thinks might help them and their families go on with their lives: birth control, books, money for groceries or child care or Christmas presents.

Embracing the idea of reproductive justice, Roberts is not just providing the means to abortions. Part of her goal is to create a rare experience: shame-free, holistic bodily autonomy. Ideally, in the socialist paradise of our dreams, organizations like the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund still exist, but are funded by the state, maybe as part of Medicare for All. But we don’t live in that world yet; we live in a world where the Democratic Party is still led by lukewarm centrists worried about alienating a relatively small number of anti-abortion constitutents, and where even Bernie Sanders can be slightly squishy about abortion rights.

To that end, we have to band together, and not just advocate or mobilize, but also find ways to organize, both inside and outside of the law, in order to provide care for each other. That may look like walking a sidewalk as a clinic escort, canvassing with your local DSA to build support and gather pledges supporting Medicare for All, or offering childcare or food for on-the-ground activists who have been working on securing reproductive freedom for decades. It may mean creating or joining a collective along the same lines as Jane. “Care” is an old liberatory feminist term, encompassing a much bigger emotional and material concept than the narrow framework of a legal right. Defending the right to privacy under Roe, and making half-assed exceptions for trimesters and abuse, isn’t enough. We have been losing for so long. We need to go on the offensive. It is completely insufficient to defend an abstract law. We need to defend each other.