Malcolm X did not have to die. He could have avoided it. He chose not to. Then again, because one can’t imagine him choosing differently, perhaps he did have to die. Such a man as Malcolm simply could not do otherwise.

Malcolm’s assassination is awkward to fit into a political narrative. Martin Luther King was killed by a white racist, while Malcolm was killed by black members of the Nation of Islam. Malcolm spent his life antagonizing and condemning white America for its crimes against his people, yet he died at the hands of a fanatical cult and an egomaniacal leader. It seems at first such a useless, avoidable, death—if Malcolm was to be a martyr, why was this what ended him? King’s death feels inevitable, but meaningful, while Malcolm’s can seem frustrating, especially in light of the political evolution he was undergoing in his final year. Why could Malcolm not have lived to see his project through? How could Elijah Muhammed be so cruel and petty as to destroy such a singularly important individual? Malcolm had not had a chance to build a political legacy, having only left the Nation the year before his death. He survives mostly as a character rather than as a set of ideas or accomplishments. But it did not need to be that way. Did it?

Perhaps it did. Because Malcolm’s death was not absurd or inexplicable. He didn’t die in a freak accident or a random act of violence. He died because he told the truth, and wouldn’t stop telling the truth, even as it became clear that doing so would end his life. Like Socrates, he could not keep himself from asking dangerous questions. If anything, Malcolm becomes more admirable, and more interesting, because the particular truth he died for wasn’t the truth that he is most known for telling. He didn’t die because of his insistent honesty about race. He died because he applied that honesty beyond race, and questioned and criticized his own mentor. Malcolm did not just defy the authority of white America, but was committed to seeking the truth on every question.

The story of Malcolm X’s relationship with the Nation of Islam is a basic part of his biography. He discovers the sect while serving time in prison. When he is released, he becomes one of its most valued spokesmen, eventually becoming the de facto “number two” to leader Elijah Muhammed, who styled himself the “messenger of Allah.” Malcolm builds a public profile expounding the Nation’s uncompromising message of black separatism and indicting white America for its criminal history of oppression and violence.

But Malcolm and Muhammed eventually clash (not Muhammed Ali whom Malcolm seems to have been relatively close with ). Elements within the NOI believe Malcolm is getting too big, and threatening to overshadow the group’s leader. When Malcolm discovers that, in direct violation of Islamic moral teachings, Elijah Muhammed has impregnated a number of his female staff members, Malcolm makes a final split from the group in 1964. That year, he founds two groups of his own: Muslim Mosque, Inc. and the Organization of Afro-American Unity. He travels to Mecca to undertake the hajj, and comes back with a far more nuanced view on questions of race relations. Malcolm sheds a number of the NOI’s more extreme positions and its unorthodox theology, embracing ecumenical Pan-Africanism and Sunni Islam. Despite fully realizing that the NOI is a violent organization that will not tolerate mild dissent, let alone fierce criticism of its leader, Malcolm continues to publicly denounce Muhammed for his moral hypocrisy. On February 21, 1965, Malcolm is assassinated by NOI members while beginning a speech at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City.

When one watches footage of Malcolm in the last months of his life, it is obvious that he was deliberately courting death. Asked by interviewers about Elijah Muhammed’s acts, Malcolm describes them in frank detail, admitting that he is “probably a dead man already” for speaking out. Malcolm knew what was coming for him. In Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, Manning Marable writes that Malcolm could have prolonged his time abroad until tensions with the Nation died down, but chose to return to the United States and continue pointing the finger at his former benefactor. Malcolm could not stomach what Muhammed had done, and felt guilty for having sold people on Muhammed’s infallibility. He insisted on clearing his conscience.

Because Malcolm died young, and did not live to build the Organization of Afro-American Unity into a major political force and one can look back and wonder what he stood for and what he should mean to the left. Certainly, the posthumous Autobiography is a classic depiction of the awakening of political consciousness. But civil rights leaders of Malcolm’s time were not wrong in pointing out that his activities had made him politically marginal, that there were not obvious material gains that can be traced to Malcolm X.

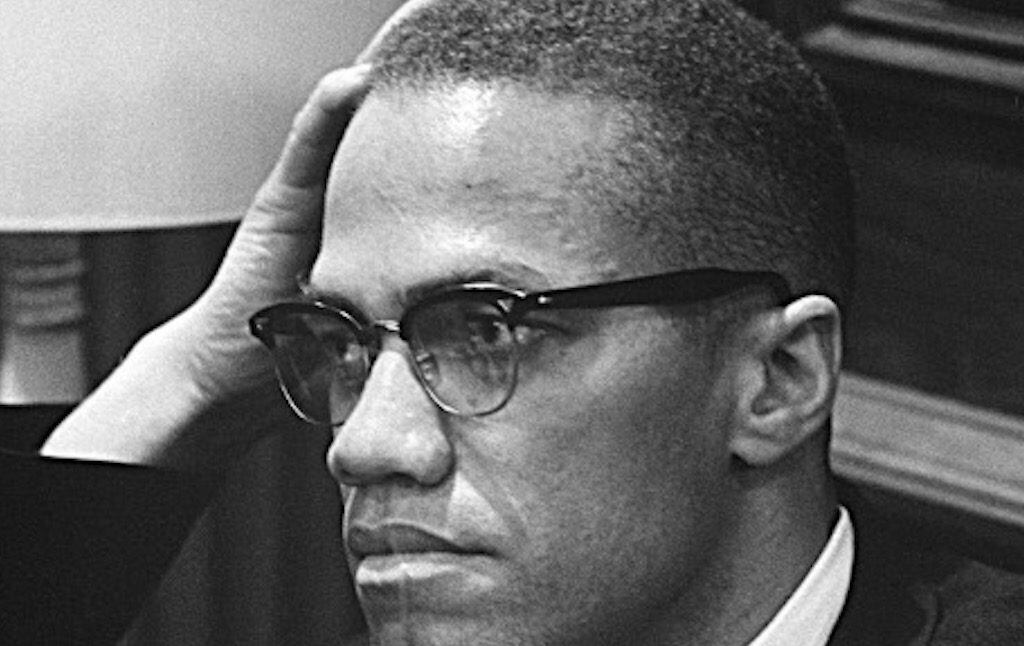

One can get a better appreciation for why Malcolm X matters by watching extant videos of his interviews, debates, and speeches. The acclaimed Autobiography, written in collaboration with Alex Haley, doesn’t come close to capturing the presence that one sees in videos of Malcolm in action. It only takes a few minutes of watching and listening to him to realize that Malcolm was unlike any other public figure of that or any other era. Smolderingly handsome (Maya Angelou said: “His aura was too bright and his masculine force affected me physically… A hot desert storm eddied around him and rushed to me, making my skin contract and my pores slam shut.”), he seems somehow more alive, more contemporary, than other figures from early ’60s black-and-white television. In debates, he is quick and charming and flummoxes his interlocutors. In a 1963 City Desk appearance, he capably “destroys” three white men who attempt to penetrate his logic and embarrass him. In one memorable portion, a panelist tries to maneuver Malcolm into revealing that he was not born with the last name “X”:

PANELIST:

What is your real name?

MALCOLM X:

Malcolm. Malcolm X.

PANELIST:

Is that your legal name?

MALCOLM X:

As far as I’m concerned, it’s my legal name.

PANELIST:

Would you mind telling me what your father’s last name was?

MALCOLM X:

My father didn’t know his last name. My father got his last name from his grandfather, and his grandfather got it from his grandfather, who got it from the slavemaster. The real names of our people were destroyed during slavery.

PANELIST:

Was there any line, any point in the genealogy of your family when you did have to use a last name, and if so, what was it?

MALCOLM X:

The last name of my forefathers was taken from them when they were brought to America and made slaves, and then the name of the slavemaster was given, which we refuse, we reject that name today.

PANELIST:

You mean, you won’t even tell me what your father’s supposed last name was or gifted last name was?

MALCOLM X:

I never acknowledge it whatsoever.

Every exchange is like this. Malcolm is cool, unflappable, logical. His questioners are patronizing and relentless but get nowhere. If you were black in the early ’60s, you would not have seen anything like this on television before. A man who ran circles around whites in debate, who didn’t soften his language, who didn’t pat people on the back for civil rights gains, who implied that John F. Kennedy got what he deserved. Malcolm was terrifying, in part because while he advocated armed self-defense, he did so in a gentle, rational tone that made violent struggle appear intellectually serious.

Those who knew Malcolm were struck by the same quality that comes across in video and audio recordings: the quickness and calmness of his intellect. Marable quotes an observer:

“Malcolm would be the last person to say anything. He’d let people air out what they had to say. And then he’d say ‘Can I say something?’ You could hear a pin drop. And he said, ‘Sister so-and-so has a good point, and she thinks she’s in opposition to Brother so-and-so. And Brother so-and-so has a good argument. But—’ And he would synthesize the whole argument. He would show everybody their strong points and everybody their weak points and how everything interrelated… It was amazing.”

Marable reports that Malcolm was so persuasive that a racist police officer, tasked with listening in on Malcolm’s speeches and phone calls, was eventually swayed by Malcolm’s words and told superior officers that Malcolm was right.

He also had a gift for phrasing. When Malcolm criticized mainstream civil rights leaders for not moving fast enough, when he denounced white America for its crimes, he did so in language impossible to forget. A few choice quotes:

- “How can you thank a man for giving you what’s already yours? How then can you thank him for giving you only part of what’s already yours?”

- “Give it to us now. Don’t wait for next year. Give it to us yesterday, and that’s not fast enough.”

- “Any time you demonstrate against segregation and a man has the audacity to put a police dog on you, kill that dog.”

- “Whenever you’re going after something that belongs to you, anyone who’s depriving you of the right to have it is a criminal. Understand that. Whenever you are going after something that is yours, you are within your legal rights to lay claim to it. And anyone who puts forth any effort to deprive you of that which is yours, is breaking the law, is a criminal.”

- “If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress. You pull it all the way out, that’s not progress. Progress is healing the wound that the blow made. And they haven’t even begun to pull the knife out, much less heal the wound. They won’t even admit the knife is there.”

- “If violence is wrong in America, violence is wrong abroad. If it’s wrong to be violent defending black women and black children and black babies and black men, then it’s wrong for America to draft us and make us violent abroad in defense of her. And if it is right for America to draft us, and teach us how to be violent in defense of her, then it is right for you and me to do whatever is necessary to defend our own people right here in this country.”

Malcolm said at one point that in another world, he might have become a lawyer. Thank goodness he didn’t, but one can see that he had a kind of “legal mind.” He often proceeds deductively. If (1) segregation is illegal and (2) the police are trying to uphold segregation, then (3) the police are criminals and should be treated as such. If (1) black Americans do not have the right to vote and (2) unless a government is democratic, it is a tyranny, then (3) black Americans are within their rights to resist the United States government by force of arms, just as the American revolutionaries resisted the British. If (1) people have the right to defend their bodies from attack (2) police are setting dogs on black people’s bodies, then (3) black people are morally and legally permitted to kill police dogs. Malcolm gave people the chills in part because they didn’t see how his reasoning could be escaped.

Malcolm’s arguments are important because so many of them are right. He demands moral consistency: If it is wrong for black people to resist violently, then U.S. imperial violence is wrong. You cannot condemn one and excuse the other. His ideas about progress and entitlement are particularly essential. We should not say that we have “come a long way” or that things are “getting better,” because it’s like drawing the knife out a few inches and calling it “progress.” If civil rights are a basic, non-negotiable entitlement, then the correct time for them to have been granted is the day before yesterday, and every day that they are not granted is another day that the state has no legitimacy. Malcolm was not just angry; he made arguments that anger was rationally compelled.

Many of Malcolm’s interviews involve white people asking him why he believes in “hate,” and Malcolm patiently explaining that he does not. The famous 1959 Mike Wallace documentary on the Nation of Islam, The Hate That Hate Produced, set the tone for future reporting. At the end of the Autobiography, Malcolm not only forecasts his own death but correctly predicts future portrayals of his ideas:

Each day I live as if I am already dead, and I tell you what I would like for you to do. When I am dead—I say it that way because from the things I know, I do not expect to live long enough to read this book in its finished form—I want you to just watch and see if I’m not right in what I say: that the white man, in his press, is going to identify me with ‘hate.’ He will make use of me dead, as he has made use of me alive, as a convenient symbol of ‘hatred’—and that will help him to escape facing the truth that all I have been doing is holding up a mirror to reflect, to show, the history of unspeakable crimes that his race has committed against my race. You watch. I will be labeled as, at best, an ‘irresponsible’ black man.

Malcolm made it repeatedly clear throughout his public life that he never believed in “hate.” But it’s true, as Marable points out in A Life of Reinvention, that Malcolm was often inconsistent in his statements. Sometimes he appeared to be demanding nothing more than basic equality, sometimes he appeared to be a separatist. Sometimes he would promise to work with civil rights groups to achieve common ends, sometimes he was denouncing them as Uncle Toms who could offer nothing to black people. There are ugly anti-Semitic remarks from Malcolm’s NOI period, and at one point he appeared to have believed the Klan could be a valuable ally because of their mutual interest in nationalism and racial separation.

But one reason to be fascinated by Malcolm today, and to study him, is that he consistently learned and evolved. Marable calls this “reinvention,” but it’s not a fair term, as it implies a kind of deliberate shape-shifting, as if Malcolm came up with new phases like David Bowie. Instead, Malcolm was always taking on new knowledge. If he was inconsistent, it was in part because he was continuously trying to work out exactly what he thought. There are difficult intellectual dilemmas about race politics (e.g., to what extent should identity be the locus for organizing?) and Malcolm was grappling with them. He didn’t figure out his answer before he was killed, but he was making new discoveries all the time. In Malcolm X Speaks, a posthumous collection of his public statements, Malcolm talks about the need to think for one’s self, examine presuppositions, and try to make sure that one has not accidentally taken enemies for friends and friends for enemies. He recounts an incident in which a woman sitting next to him on a plane looked at his suitcase, with an X stamped on it, and asked what kind of last name began with X. Malcolm told her that the X was his full last name, and that his first name was Malcolm. “You’re not… Malcolm X?” she replied. “You’re not what I was expecting.” Malcolm uses the woman’s surprise to illustrate the power of prejudice, and to caution readers against making the same mistake.

Famously, after his trip to Mecca he became uncomfortable with black nationalism, because he had seen blue-eyed Muslims who worshiped the same god he did, and he saw Algerians engaged in the same anti-imperialist struggle that he identified with. Malcolm’s Muslim faith and his strong black identity were in interesting tension—a tension that came to life in the disputes between members of his Muslim Mosque organization and his Organization of Afro-American Unity.

Toward the end of his life, Malcolm was producing some of his most sophisticated, and contradictory, analysis. As Marable points out, Malcolm “took different tones and attitudes depending on which group he was speaking to, and often presented contradictory opinions only days apart.” He was attempting to work out his feelings on socialism and capitalism. He said he didn’t think it was an accident that so many Third World revolutionary movements were socialistic, and that “you can’t operate a capitalist system unless you are vulturistic; you have to have somebody else’s blood to suck to be a capitalist.” He was particularly adept at points and joining the inextricably linked struggles against white supremacy and capitalism “It’s impossible for a white person to believe in capitalism and not believe in racism.” At the same time, he would make qualifying statements like: “I am not anti-American, un-American, seditious nor subversive. I don’t buy the anti-capitalist propaganda of the communist, nor do I buy the anti-communist propaganda of the capitalist.”

As Adolph Reed, Jr. writes in his essay on Malcolm, this fact has made it almost irresistible to speculate on what Malcolm’s next phase would have been:

“It is all too tempting to play the what-Malcolm-would-do-if-he-were-alive game, but the temptation should be avoided because the only honest response is that we can have no idea. Part of what was so exciting about Malcolm, in retrospect anyway, was that he was moving so quickly, experimenting with ideas, trying to get a handle on the history he was living.”

Reed suggests that instead of daydreaming about possible Malcolms of the ’70s and ’80s, we should embrace Malcolm’s conflictedness as a core part of our image of him. We should get past Malcolm the icon to see Malcolm the human being, a person all the more impressive for being flesh and blood just like ourselves:

“It seems to me that the best way to think of the best of Malcolm is that he was just like the rest of us; a regular person saddled with imperfect knowledge, human frailties, and conflicting imperatives but nonetheless trying to make sense of his very specific history, trying unsuccessfully to transcend it, and struggling to push it in a humane direction. We can learn most from his failures and limitations because they speak most clearly both of the character of his time and of the sorts of perils we must guard against in our own. He was no prince; there are no princes, only people like ourselves who strive to influence their own history. To the extent that we believe otherwise, we turn Malcolm into a postage stamp and reproduce the evasive reflex that has deformed critical black political action for a generation.”

What does Reed mean about “evasion” “deforming” political activism? Perhaps that when we see political figures of times past as two-dimensional heroes, we forget the reality of organizing, fail to see that it is done by organizers, who are people like us, and thereby make it harder to imagine that we ourselves could continue their work. But Malcolm is undeniably human, in the most honorable sense. The more like us Malcolm seems, the more responsible we are for trying to finish what he left undone.

Ossie Davis, in a postscript at the end of the Autobiography, gives his own take on why Malcolm’s life has enduring value. Davis says that he often disagreed with Malcolm, but that:

Whatever else he was or was not—Malcolm was a man! … Protocol and common sense require that Negroes stand back and let the white man speak up for us, defend us, and lead us from behind the scene in our fight. This is the essence of Negro politics. But Malcolm said to hell with that! Get up off your knees and fight your own battles.

Davis says Malcolm “kept shouting the painful truth we whites and blacks did not want to hear” and “wouldn’t stop for love nor money.” That’s why it’s correct to place him in the tradition of Socrates, to see him not necessarily as a model revolutionary but as a model truth-teller, a person whose respect for himself and others was too great to allow him to compromise. Davis and Reed are right that it’s Malcolm’s character, rather than his politics, that we can take most from today. His politics, after all, were in flux. But his character was firm, and he showed the same courage in taking on Elijah Muhammed that he had in doing speaking engagements in Mississippi. From Malcolm, we can’t learn what we ought to do, but we can learn how we ought to do it: with the same courage, resolve, dignity, and crisp intellect. Malcolm is a model of how to be sharp and committed in impossible circumstances, how to run rings around your oppressors by calmly demolishing their propaganda. Was he flawed? He’d be the first to say yes. But the short career of Malcolm X still has much to teach us about how to be smart, how to be brave, how to be good, how to be flawed—how to be a person. Very few of us will ever become as alive over a long life as Malcolm X was in such a short one, but we ought to try harder.