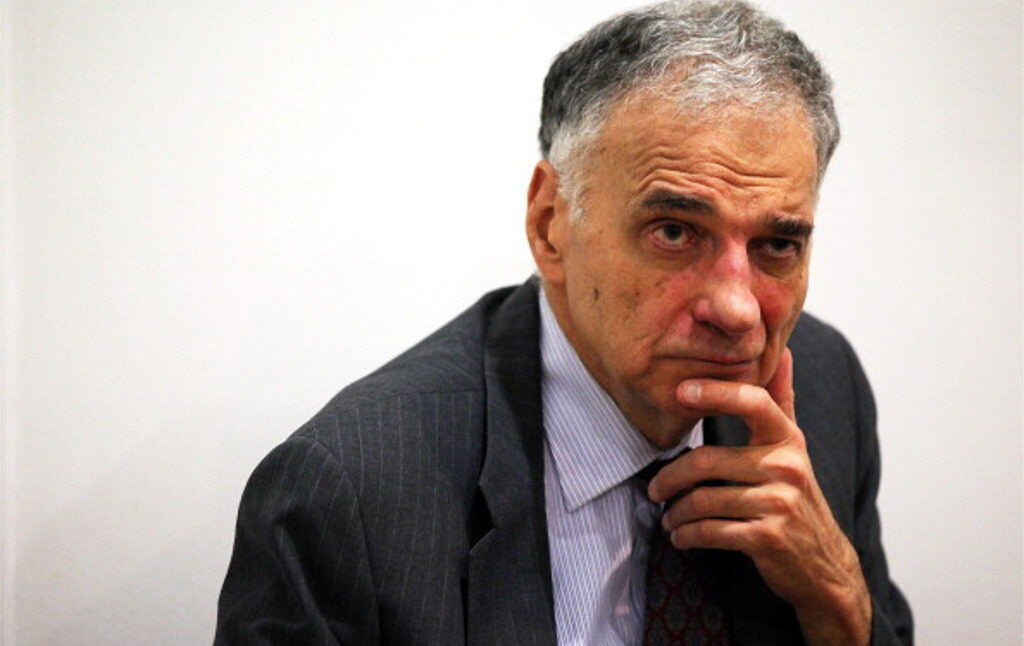

INTERVIEW: Ralph Nader On His Crusading Career

The veteran consumer advocate on how to change the world…

Ralph Nader recently spoke to Pete Davis on an episode of The Current Affairs Podcast. A transcript follows. It has been edited lightly for grammar and clarity.

Pete Davis: We have a very, very, very special episode today. There are a few superheroes in the Current Affairs pantheon, and we are lucky to have one of them with us today: consumer advocate, and public citizen extraordinaire, Ralph Nader. Thank you for coming on Current Affairs.

Ralph Nader: Welcome. Pleasure.

PD: Later in the interview, Ralph, I want to get your views on what is happening in politics today. But before we do, I think listeners could learn a lot from—I sure have learned a lot from, in my life—hearing about your process, some of the strategic decisions you have made, and civic innovations you have realized in your creative crusading career. So, may we journey into the past?

RN: Full throttle.

PD: Let’s do it.

So, let’s begin from the very beginning. Many of our listeners are young, some of them are in their teens, some are in their 20s, some are in their early 30s, and you started your famous career in your 20s. And I’d like to know—we know the myth: we know that you had friends who were hurt in auto—it’s a truth myth, but we’ve heard the epic story: your friend is hurt in auto industry crashes, you eventually write Unsafe At Any Speed, then you’re in the White House a few years later with Lyndon Johnson, signing the Highway Traffic Safety Administration bill. But I would like to go to really, what is that first moment you’re in law school and you decide, “I’m not an engineer, I’m not an expert in this field, I’m just a twenty-something, and I’m going to start researching this, and I think I can make a difference?”

RN: I started in my teens, early teens, reading. I read, read, read, read, read, read. Once in a while, I would turn on WINS and listen to the Yankee games, and I read, and I read. Why am I repeating myself? Because almost everybody I’ve ever met knows how to read, but that doesn’t mean they read—they’re aliterate. And, so, because I read, I read the history of the muckrakers, the people in the early 20th century who exposed the dirty food, unsafe working conditions, concentrated power of John D. Rockefeller’s oil companies, Ida Tarbell, for example, and I was absolutely inspired and excited. My hands would tremble with the books in them. That’s how excited I was. So, I said to myself, there’s a lot of work left to be done. Because I read newspapers, I saw a challenge.

PD: So, you were primed: you wanted to be like your heroes, you collected heroes to begin with. I’ve heard that it was your third-year law school paper that was the first writing you did on auto safety.

RN: Yes, we all had to write a third-year paper, and most of the students were sort of stimulated by the professor, who wanted some free research done for some longer article, or some very minor provision to the Securities Act, they would elaborate on, and I said no, I want to do it on why the law hasn’t caught up with General Motors, why there are no mandatory safety standards for motor vehicles. Why, given that it was then the first leading cause of death between ages five and 24—which included law students—the federal and state governments were doing nothing. And so, I enlisted into what’s called the medical legal seminar, and I wrote a paper, “Unsafe Auto Design And The Law.” Well, there was no law, but I recommended one, and I turned it into the book, Unsafe At Any Speed, a few years later.

PD: I think some young person, today, if they read an article about some other issue, they would probably say, “I’m not an expert, there’s probably already some other person working on this. Who am I to do this?” How did you get to a point where you felt like, “I can come up with a whole new body of laws, as a law student?” Because law students today, and all students, are told, “let the adults handle it. We already have someone figuring it out.”

RN: Well, it’s obvious that the function of lawyers is to translate fact into reality. So, if they have information about unsafe pharmaceuticals, or flammable fabrics, or corruption in politics, who is the expert? If there is an expert, it’s a lawyer. The law is supposed to tame raw power, supposed to subsume raw power, discipline it, displace it, undermine it, channel it in a different way. So, I never had any problem with that, because there’s an old Roman adage called “out of the fact, comes the law.” So, as long as I read the human factors: engineering, the crash-worthiness studies, Cornell Medical School, Harvard School of Public Health—there weren’t that many at that time, and surprisingly, they were funded by the Pentagon, because the Pentagon realized they were losing more Air Force men on highways in the U.S. than in the Korean War, and so they started funding Cornell Medical School. How do you make cars so that, when they do crash, due to whatever problem—roads, weather, drunk driver—the car is built to allow you to survive, with seatbelts, padded dash panels, stronger latches, all the rest. So I had no problem with that. The ultimate profession in the United States of America that is the catalytic one—that brings in medical information, engineering information, scientific and statistical information—is the legal profession, and I take it seriously.

PD: I want to talk about all these exit ramps you could have had. So, you could have had an exit ramp of hearing about car crashes, and not done anything about it. You didn’t take that exit ramp. You said, I’m going to write about it. You then could have had an exit ramp that said, “I wrote a great book. Now, everybody knows.” But you didn’t stop there. You turned it into lobbying. And I’d love to hear how you didn’t just sit satisfied that you wrote a good book about a problem, and then leave it to other people to figure out. How did you decide to become someone lobbying, to realize the goals of your book?

RN: Because I started with fire in the belly, and then I filled my head with information, and I connected it to fire in the belly. People who knew a lot about auto safety, after Unsafe At Any Speed came out in 1965, would tell me, “We should have written this book. I mean, we know all kinds of things about the industry, and what they’re not doing.” And said, “Well, why didn’t you?” And the unspoken answer is: they didn’t have fire in their belly. And I lost a lot of friends, and a lot more of them are paraplegics—quadriplegics never survived in those days—and I said, those sons of guns in Detroit, they’re sitting on palatial styling expenditures, and they don’t have many safety engineers, and they’re paying themselves huge money, and they’re selling psychosexual dreamboats called cars, and people are dying every day all over the country, being ripped apart. And so it’s not that surprising, Pete. The surprising thing is why more people don’t have fire in their belly. They all have bellies right? They often know. Why don’t they have the turbo-charge of cognitive knowledge, emotional intelligence? We call it, now, fire in the belly.

PD: So, I’ll reveal to listeners, I used to work in your office with you. And my favorite story, when anyone ever asks me, “What was it like working there?” I always tell them this story: You brought me into your office about the third week, and I wasn’t doing enough. I was assigned to fight Walmart, and to raise wages of workers. You pulled me into your office and you said, “Pete, I have a lot of people I know who went to your college, and a lot of people from that college think they’re very smart, and they think they know everything. But they don’t have fire in the belly. And you’re going to be able to get by, having a normal career, with the level of smarts you have. But if you don’t develop fire in the belly, you’re not going to take on Walmart, and you’re not going to be able to raise these wages, and you’re not going to be able to get there with your head. So, this weekend, I want you to read five books on Walmart before the end of the weekend. I said, five books? I’ve never read five books in a weekend. And you said, “You can do it, if you have fire in the belly.” And I went home that weekend, and I just started reading, and I got to three-and-a-half. And I came back, “Oh, Ralph, I’m so sorry.” And you go, “but I showed you what you could do, when you turn on that furnace inside of you.” And I’ve never been the same, ever since that conversation.

RN: I never was aware of that. I’ve got to do that with more young people. The problem is, you talk to most people about the most horrendous injustices and cruelties, the brutalities, and most of them just look at you, and they thank you, and the session is closed, and they drift away, looking at their iPhone. I think the iPhone is devastating. I think it’s shredding their minds. We don’t have to go into great detail, but it cuts out human interaction. Most of these, you see so much brutality in fiction, on the internet, and everywhere, that they’re sort of immune from a sort of horrific reaction that they might have if they had never seen it on film.

PD: Some people call it, a young person word, “irony poisoned.” They become so ironically distanced—oh, everything’s awful, I know. You know, look at this awful country we live in. But you can’t be that if you want to fight. The people who fight don’t get that sarcastic attitude about it.

RN: Yeah, cynicism is the enabler of plutocracy and oligarchy. They love cynical citizens, because the next step after you cynically express your “pox on all houses,” is you withdraw. And if you withdraw, you’re not a factor. And you create a vacuum, and as the old saying goes, power abhors a vacuum, and fills it. So they love cynical people. They don’t like skeptical people who come to similar negative conclusions, but they don’t give themselves the excuse of quitting. They go forward, trying to change the equation.

PD: Yeah, it’s the difference between “everything is awful” and “many things are awful, but some things are good, and we should support those things, and fight these things in particular ways”…

RN: Kind of strategically. I mean, look how smart people are when it comes to sports: they know the strategy, the tactics; did the manager make a mistake, what was the batting record of a certain batter; how should a pitcher pitch. Imagine if people were that smart about democracy, about practicing democracy, about being civically active. The contrast is stunning. You turn on these sports radio shows, and you get calls from ordinary sports fans that are incisive, and challenging, and knowledgeable. But when it comes to voting, comes to congressional candidates, state legislative candidates, it’s okay to be a five-minute voter, half of whom don’t even vote. A five-minute voter just says, “yeah, that person looks pretty good. I like that slogan, you know, Make America Great Again. And y-y-you know, he really cares for people, he at least says so. I’m going to vote for him.” Or “I don’t like the other person, for various catchy reasons.” They don’t do the record, they don’t do the analysis. They don’t understand that they’re sovereign, under the Constitution. They are the sovereign people. I mean, young people should get up in the morning, and say, “We the People.” Because the Constitution doesn’t start with “We the Corporation” or “We the Congress.”

PD: It’s hard to get from a five-minute voter to Ralph Nader in one day. But the way it usually happens, I’ve noticed—and the way it seems to have happened in your life—is it snowballs. You start digging away at something, and then you keep digging, and you keep digging, and it becomes a bigger part of your identity, and it becomes more enjoyable as you get deeper. And you actually become more hopeful, as you act, and then suddenly, you can’t not do it anymore. And what happened with you, is you start thinking these heroes are muckrakers, you start digging away at this issue, you write a book about it, then you have to act on it, and then, this next part of when it snowballed, again, is, one exit ramp, is you could have been a one-issue pony. You could have started the Center For Auto Safety and you could have been the head of it for 50 years, and that would have been all you did. But what you decided to do, was you metastasized. So, I’d love to hear about this thing where you went from one issue—and you could have been famous, and friendly with everybody—to becoming an every-issue person. How did that happen?

RN: Well, first of all, I didn’t metastasize, I diversified. The corporations think I metastasized.

PD: Correct the metaphor, Ralph [laughs].

RN: It happened because I studied history, and people wrote great books, and went nowhere. That was happening all the time. I studied what happens when you’re a Lone Ranger, up against thousands of corporate adversaries and their political cronies: they wear you down, they wear you out, you get discouraged, and you eventually drop out. Or, they just defeat you, because you don’t have the soldiers on your side. So, I started a lot of new groups, for several reasons. One, is we can’t have too many citizen advocates. They’re needed everywhere, and there are whole areas where there’s nobody. Nobody watching the government to regulate imports of drugs from China and India, nobody looking over at the Pentagon, and the budget. It’s just amazing, the gaps, great opportunities for young people to fill with their own groups. The other reason is that I always defined leadership as “producing more leaders, not followers.” I really don’t like to give orders. I may give advice, but I’m not a control freak. And that made me very, very willing to find young people, on their own projects, they get authorship of books at age 23, 25. I may write the introduction, but I don’t grab the authorship the way some group leaders do. And that’s the way you build leaders.

So, if you really want a just society, you want to win. And if you want to win, you have to have thousands of civil advocates, and leaders, and graphic artists, and organizers, and canvassers, and we’ve started maybe 100 groups around the country, in Washington—public interest research groups among the more numerous. But if we had a couple of breaks here and there with a Supreme Court decision, or with a Congress as good as it was in the late ‘60s, we’d have tens of thousands of citizen groups, and then you couldn’t describe what a wonderful country this could be: we’d have full health insurance, we’d have living wages, we’d have more progressive unions, we’d have a peaceful foreign policy, we wouldn’t have an empire devouring our country and destroying people abroad. It symbolizes a book I just recently wrote, called Breaking Through Power Is Easier Than We Think. I’ve got to hammer that home: it’s easier than we think. We got the auto industry regulated, I don’t think I had 300 people out there around the country: some engineers, some doctors, some citizen advocates, focusing on Congress. Why did we do it? How did we do it? Because, we asked ourselves: who in the entire United States can make the auto companies build safer cars? Well, it’s not your local mayor. It’s not your local PTA. It happens, the way we’re organized: Congress. It’s Congress.

So the idea of young people getting all kinds of rallies on the global disruption of the climate, and so on, it’s all going to go into the ether, the energy, unless it is directed to the Parliaments, and the Congress. Talking about 535 people in the Congress, you start out with about 150 on your side anyway. We’re millions of people out there. If we need 1% of the people, or less, organized, with the majority behind them, in each congressional district, presto, you’ll see how you can overcome Exxon-Mobile, Peabody Coal. You know, people don’t get this message. Young people don’t get this message at all. And I’ll tell you why: it’s because they don’t read. They don’t read the kinds of books I read, and others who have led the way out of the 1950s and 60s, and civil rights, and women’s rights, corporate rights, consumer, environment, worker movements.

PD: It’s funny that when you read, you learn two things at once: you learn it is worse than you think, and there needs to be someone who works on it. But then it’s more hopeful than you think. There are so many examples in history where people overcame things.

RN: Yeah, and the more outrageous it is, the more motivated your psychic energy should be. You see, you have got to build in a civic personality, is what I call it, where the more outrageous the injustice, the more it makes you active and determined, rather than discourages you, and gets you to quit.

PD: And you’ve mentioned this model of what you started in the late ‘60s, early ‘70s, which was the Nader’s Raiders model. You took young people, you assigned them a task, then you monitored them, they wrote a report, and then lobbied around it. They used your name to get attention, but then you let them put their name on it to get attention for them, so they left it being an influential person as well. You created leaders. Lori Wallach, this is my favorite quote about it, she said, “passing through your office was like training with Yoda to be a Jedi. And afterwards, you’re a Jedi.” And I felt the same way, passing through your office, and I’d love to hear your reflections on that model.

RN: First of all, we don’t take young people seriously enough, the adults. It takes a long time to grow up in America, and I wanted to disprove that. The best example is: I got a letter once from some high school students in Connecticut, worried about nursing home abuses. So, I went there to speak and I recruited them. And six of them, with their young teacher, came down to Washington. They had spent some time volunteering in nursing homes in Connecticut, so they got a sense of what the scene was, and they dug into the files of the Department of Health, Education, Welfare, inspection reports, the lack of regulation of nursing homes, terrible mistreatment, over-drugging elderly people, lack of sanitation, bed sores, on and on. And so, immediately, before they went back to school—they were 17 years old, and they were all young women. People would say to me, “What are you doing? These kids, they can’t understand this.” I said, “They know how to read, and they know how to think, and guess what? They have something you don’t have: idealism. They’re motivated. They’re worried about the elderly and how they’re treated.” and so, they wrote a book. It was called Old Age: The Last Segregation, 1,000,000 Americans In Nursing Homes.

And look what happened: in just a few weeks, they testified for the Senate, they testified for the House, they had press conferences, the news spread all over the country, and they helped reform nursing homes. It was still a lot of work to do, but it was a big jump forward. And this was before they even entered college. And so, I went back to the skeptics, and I gave them the book, and I said “You really think they weren’t capable of doing this?” Just think of the human resources that are lost just because of this ridiculous prejudice that just because they’re not 28 years old or whatever, they can’t do important, justice-advancing work. So, we did it with college students, we did it with graduate students, with law students, and it’s just too bad that other civic leaders didn’t pick up on the same thing, because, as the Vietnam War wore down, and the fervor from the ‘60s wore down, it became more and more difficult to recruit students who wanted to do this type of work.

PD: It’s funny, in all the industries where we empower early twenty-somethings, it always works out, and it’s an amazing thing. In sports, we tell these twenty-somethings, you have to be the leader of this team. Saturday Night Live, Lorne Michaels throws these 24 year old writers, and 23 year old writers into a thing, and they make a national television show, and they all become famous people. And we don’t do that in civics. Usually, twenty-somethings, you have to ladder-climb, and you have to spend your time getting coffee and listening to some older person. And you invert that to say we’re going to immediately empower you. An amazing thing. One other aspect about your early rise I’d like to ask about is: there’s this very interesting parallel movement to the right’s revolutions of the 60s and 70s. So, the Nader revolution of the 60s and 70s is happening at the same time as civil rights, women’s rights, anti-war, gay rights. All the other movements—big marches, big campus unrest, big cultural shifts—people are wearing their hair in different ways. They’re talking in different ways. But meanwhile, yours stands apart, because you’re a bunch of lawyerly report writers. If it’s fair for me to say, you kept a 1950s aesthetic, with like, wearing your suit. You did much less national giant marches in the ‘60s and ‘70s. It was much more persuasion in Congress. And I would love to hear, how did you relate, at the time, to the other unrest that was happening? Did you think about yourself as part of that other social change? Or were you truly just kind of in your own parallel lane?

RN: Well, we benefiting from them, because they were viewed as so radical, we weren’t considered so radical, trying to get health and safety regulations on corporations, and so, I credit the anti-war movement, the women’s rights movement, the student movement for making us look rather moderate by comparison. As far as dressing up, I realized I never wore a necktie, until I was about 18. I actually kept away from my sister’s graduation ceremony at Smith College, because I wouldn’t wear a necktie. And that made a big impression. I said, you know, I’m the same person. They kept me away because I didn’t have some textile around my neck?

PD: So you had a little bit of the ‘60s, kind of question authority thing.

RN: Yeah! And then, I resolved I was never going to give anybody an excuse not to meet with me in Congress, not to interview me in the press, because I had dangling long hair and disheveled clothing. And that’s why all the Nader Raiders, they didn’t dress in tuxedos, they had long hair, but they dressed “properly” so they couldn’t give anybody an excuse. I remember, once, I was on a subway, and there were some young people with placards and all. And a woman turned to me and she said, “I hate that long hair, and they smell.” And I said, you know, they want to end the Vietnam War. She said, “that may be all well and good, but I don’t like the way that they look.” You see what I mean? You got to worry about trivial distractions that become substantive blockades, keeping you from getting to where you’re going.

PD: I want to run this theory by you that I have, about two types of activists that I’ve noticed. I call them the “soil” versus the “sky.” The “sky” activists start from abstract, structural theory. They sit alone, and they think about a just world, and then they look at the world, and they say, we need to move it from what it is to these ideas that I have. And then they have to get very concrete to start moving the world in their direction. The soil people start from real-world problems they see in the newspaper, or among their clients as a lawyer, and later they notice the structural patterns that happen. So the reason I discovered this is because Catherine MacKinnon, who popularized the idea of sexual harassment at work, I asked her “Oh, did you think about what a just workplace was?” And she said, “No, no, no. I had a bunch of clients, and every client started telling me ‘Oh, my gosh. This awful thing is happening at work,’ and then I do each of their cases one by one. And I said, ‘Oh! There seems to be a pattern here. Let me name it,’ and then I named it sexual harassment.”

You seem very like a soil activist in that you’re reading the newspaper, you’re getting letters from people— a lot of your issues come out of the real world. It’s very concrete. I would love to hear if you think about yourself that way.

RN: It’s a very profound question, if the listeners have the patience to listen to the answer. What Pete was describing, basically, has been ruminated on in scientific circles for years. What you say is the “sky” is the inductive method. You develop a scientific theory, and then you try to test it empirically, on the ground. The soil metaphor is the deductive method: you look at what’s going on, say, with waves—Benjamin Franklin, when he was crossing the Atlantic, he checked the waves, and he started developing a theory on ocean waves. The consumer movement has been very empirical. Part of it is a fallout from the McCarthy period, when ideologies, like leftist ideologies, were skewered by McCarthy’s slander, distortion, and harassment. These are people who might be called socialists, who might be called Communists, they might be called reformers, but he turned them into Communists, because they wanted to have land reform in third-world countries, or whatever, and there’s probably overreaction from that, from people who went to college in the ’50s, and they got into the consumer movement, and they started talking about dirty meat plants, they started talking about hazardous over-the-counter drugs. They started talking about pajamas burning kids to death, because they’re flammable. And then they moved towards recall, standards, prosecutions, and civil justice lawsuits, tort lawsuits. And they never got any higher toward the sky. And years and years ago, we had a discussion around the dinner table in my family. My father once said, “who do you think is more powerful in the world: people who think, or people who believe?” Obviously, it’s people who believe. Ideologies, religions, mass movements. People who think, maybe they feed a belief pattern later, but the problem with the whole citizen movement, call it what it is, civil rights, civil liberties, women’s rights, African-American justice, prison reform, tax reform, corporate crime prosecution—if it doesn’t go toward the sky, it’s never going to catch the imagination of the popular will. It’s really strange, because you say to people, “Do you care about dirty meat, when you go into the supermarket, it’s contaminated?” “Of course! I don’t want to touch it.” And you think that’s enough, but it isn’t enough. The human being, regardless of formal educational levels, craves some sort of pattern, consistent belief to cling to, and to adhere to everyday.

PD: So, it seems to be this dance, because, I was about to say, the benefit of the soil is that I ask a lot of my Republican friends—who have Republican parents, I go, oh, you know, I used to work for Ralph Nader, what do you think about Ralph Nader? The Republicans tend to like you more than they like the Democrats. And I go, “in many ways, he’s left of Hillary Clinton or Barack Obama, but you like him more.” And what they liked about you was that you were able to get to them through the soil. If you started with “down with corporate power,” they would turn off. But when you say, “Aren’t you worried about your kids breathing dirty air?” they would like you. But, so that’s the benefit of the soil, you can reach across the aisle on the concrete issues. But what you’re saying, is the downside of the soil is that it doesn’t really get people that excited, to get moving. Whereas, when you say “fight corporate power,” people on our side will get ready to march in the streets.

RN: The dirty meat example justifies doing something about it, but if you don’t raise it to a higher level, of why the system in the corporate world is so messed up—the food system; contaminated food; high salt, fat, sugar, obesity. I mean, it’s a nightmare, what they’ve done to kids. And people generally, in order to cater to their taste, and melting in your mouth advertisements, and aroma, and all the rest, it doesn’t go anywhere unless you fit it into a larger pattern which says, “Look, who do you want to run this society? A few giant corporations? Whose only arch to success is the almighty dollar for them? Or do you want a deliberate process where people, in town meetings and juries, and voting, and candidates, shape the future of their families, and the future of the country, and its impact on the world?” You can’t do that with dirty meat examples. I would like to do it with dirty meat examples. You can’t. You have to have an abstract philosophy that motivates them. The problem is, once you have an abstract philosophy, and this is where the McCarthy syndrome comes in. That is very easily skewered, slandered, and turned into a horrific -ism. They can’t use the Communist -ism because they don’t exist anymore. They’ll find some other -ism. And it’s a situation that the progressive movement has never confronted. They are so empirical: what’s the next exposé? What’s the next documentary? What the next testimony before Congress? You look at all the testimony of all our groups, before Congress—hardly ever headed for the sky. We would have, for example, comprehensive nursing home standards. But we never had for more comprehensive reform of what a society should have in healthcare, which, of course, starts with prevention. It starts with nutrition. It starts with neighborhood exercise. Not spectator fans, but participatory sports.

PD: It seems like we need both. It’s a two part thing, you’ve got to have both.

RN: Because the sky needs legs on the ground, and the soil needs illumination from the sky.

PD: Thank you for playing with the metaphor, Ralph. I appreciate you running with it. It’s interesting you mention your dad, because that was my next question, coming up, which is, my dad was an activist, and very inspired by your work. And one thing I noticed about the way he did his activism is it was very much like his dad went to work. His dad was not an activist. His dad was an insurance salesman in a working class Jewish neighborhood in Pittsburgh, and his dad went to work every day with his lunch pail, and did his thing, day in and day out, very steadily. And then when my dad did his radical causework, he went to work every day, in and out, very steady, and it’s kind of like, instead of showing up to MetLife, he showed up to The Cause. And I’ve noticed in your work, your dad was a small business owner, he ran a restaurant, and your whole family participated in the running of this restaurant, and sometimes, as I was working at your office, I said, “This is very much like I work at the small business.” It had some small business qualities to it. It had loyalty to it’s employees—we’re the family of the center. It had high expectations, but high hands-on training. It had daily improvisational innovation, and it had, like, a hustle, for every single initiative, and I can imagine you hustling, selling the new pie at the diner. And I wonder if you’ve ever thought about if there was a continuity to you being…

RN: Well, the continuity was daily human interaction and feedback. We had factories right across the street, with hundreds of workers, textile factories, and they’d come for lunch, they’d come for coffee. We had juries at the local county courthouse, about 1,000 feet down the street. We had salespeople going through town. And we interacted with them in the restaurant. It was an unbelievable education. And today, just imagine how many young people never interact with human beings. They even get up in the morning and text message their parents about what they want to eat at breakfast. I’m told some young kids do that now. So, that’s one. You know how few youngsters now use regular telephones, back and forth? It used to be a major problem, in households. Stop talking so long! Mother has to use the phone! No, kids don’t want to talk human voice to human voice. They’d rather text message. There’s a price to be paid for that, you see? And you see all these kids walking down the street, they never look at the horizon. They never look up. They never look at you. You have petitioners with clipboards trying to get people to sign. Half of the people walk by and they don’t even know they’re there, because they’re doing the phone. We can’t exaggerate the devastating impact of that. So, I was lucky. I grew up with all kinds of people, all kinds of opinions, all kinds of everything from curmudgeons to pie-in-the-sky Pollyannas. Very valuable. In that sense, I always carry it with me. Once, I was walking down the street with my dad, and he said—I don’t know what caused it, but he said, “Look, when you meet with people, never look up at them, never look down at them. Just look at them straight in the eye.”

PD: A restaurant is a very democratic institution.

RN: You can’t look up, you can’t look down, you’ve got to look them straight in the eye [laughs].

PD: Amazing. Speaking of looking straight in the eye, this next one is about truth-telling among friends, and happy networks. So, Larry Summers once told Elizabeth Warren—this is one of my favorite stories about Elizabeth Warren. He sat her down, when she first started becoming famous, and he said, “Elizabeth, you can be an insider or an outsider. Outsiders can say whatever they want, but they can’t get anything done. Insiders have to tow the line, but they can, at the private meetings, sometimes have their opinions be heard.” And what Warren did, which I am proud of her for, is she immediately went to press with that story. So, we know about it, but I bring it up to queue up, how do you think about being an insider or outsider, and shooting straight, especially as you became friends with congresspeople, and became friends with different people in D.C—you live here. There are are parties. How do you balance being an insider and building connections, and being an outsider and still being able to shoot it straight?

RN: Well, you pay a price either way, obviously. However, you have greater leeway to bring your conscience to work when you’re an outsider, because when you’re an insider, you’re almost by definition part of a hierarchy, and part of a routine, and part of a pattern of self-censorship. Whether it’s a congressional committee staff, or whether it’s a government agency, or a judge’s chambers, there’s always that. So, I remember Joseph Pulitzer, the great newspaper man in St. Louis, told his reporters in Washington covering Congress, “never call a senator or a representative by their first name. No matter how many times you have coffee with them, lunch with them, went to their gatherings, invited to their homes, always say Senator So-and-So, Congressperson So-and-So.” I remembered that. I never called members of Congress by their first name, even though I knew a lot of them very well. In fact, I just spoke with Senator Cantwell. She was calling me Ralph, and I was calling her Senator Cantwell. So, that means you keep an independence that way. Once you’re on a first-name basis, you might get into some inner sanctums, but you get compromised. How do you criticize, publicly, a senator who you have called by his first name for years? See? It inhibits you.

So, outside-insider, that’s a huge story. If you’re going to be a citizen advocate, you have to be independent. If you’re independent, you have to have a significant measure of outside leverage, because you may have to go to the press, you may have to sue, you may have to expose. You may have to go and pound on the table in the Senate. However, if you can’t get access, you can be as much as an outsider as you dream, but you won’t get anything done. So, you have to have a balance, and everybody has got to work it out for themselves. There’s no rules here. There’s no judgment. But the biggest problem in the outside-inside, is if you can’t get press, you can’t be as effective as an outsider, and you can’t get inside, because a lot of senators and representatives look at you, and they say, “hey, this guy’s getting a lot of press. I have to let him in and meet with me and my staff,” where you become inside, you see? You start talking. And so, we haven’t talked about the media, but the media has never been worse in all my years in Washington, and not covering the citizen groups. And that has had a devastating blow on the democracy movement in America, including our recruitment of young people. I mean, we used to get thousands of resumes, because they turn on to CBS, ABC, NBC news, and we’d be at the top of the news! And people would see colleges, universities—hey, I want to spend a summer there, I want to go to work on this, I want to be a civic advocate, I want to be an environmentalist. They don’t see that today.

PD: So, it’s get into the inside, but not through being buddy-buddy with them, but through having your own independent source of power. One thing that happened as you did this crusading career is you became famous, and you became imprinted on American history, you’re an icon in America, and I’d love to hear what that was like, and how you met John Lennon, you hosted SNL, and I don’t want to hear what it was like for the gossip pages, I want to hear what it was like when— how do you maintain, in your soul, a commitment to a cause, when I assume there’s a lot of ego that probably comes, there’s ego risk from becoming famous. You want to live up to your icon, you don’t want to disappoint people. You know, things changed in your life. How did you handle that, and how did you keep it focused?

RN: Well, I tried not to go to any parties. I got invited to a huge number of embassy parties, press parties, congressional parties, and I would only go once or twice, just to make sure I knew what was going on in those place, so I could talk about it a bit. But I never spent much time on that. That’s one. The second, is the way I was brought up, I mean, when I became famous, and young people today don’t know how famous the press made me. I was on the cover of US News And World Report, and they did a poll of who are the most influential people in America, and I was number four, after the President, a U.S. Supreme Court Justice, and the head of the AFL-CIO. I had a meeting with my parents, who said, “Well, now that you’ve become famous, you’re going to have to learn how to endure it. Don’t let it go to your head.”

Again, this is where the focus on the victims, the deprived, the excluded, the disrespected, the harmed, helped me. That’s always my focus. When people said, “how can you challenge the Democratic Party?” I said, I’m not interested in the Democratic Party’s prospects, I’m interested in all the workers that they’re ignoring, and scuttling the Occupational Safety and Health Agency, and 58,000 workers dying every year from workplace related diseases and trauma. That’s where I get my calling. I don’t get my calling saying, “well, I have to make sure the Democrats get in, because the Republicans are worse.” That’s the Democrats’ problem. I give them the material. I give them how they can win, and stand for the people, and get votes. So, I have a real memory of people I’ve seen in hospitals, and on the highway, and that’s what drives me. I had a lucky choice of parents, Peter.

PD: Noam Chomsky says a very similar thing when he’s asked about, you know, you’re this global intellectual. He says, “I try, whenever I’m on a global trip to come speak to a large audience, I try to find groups that have been victimized by U.S. empire, and talk to them, you know, I’m always throwing coal into my engine of like, the reality of what is going on.”

RN: He does that, he does that. Your father was a great role model for you. Sandy Davis, for those of you who don’t know, was a practicing anthropologist, and his field was the indigenous tribes in the Amazon, Australia, and elsewhere. I remember we put together a big conference, where we brought natives from those far away areas to our center. So, the thing about your dad is, he was not an anthropological theorist, he started with the soil.

PD: Yes, and he had a similar thing to both you and Chomsky, where once he heard from those communities about what they needed, he doesn’t even say, I have to get inspired every morning, he says, there’s nothing I can do but help, but serve this, once you’ve seen the reality what’s going on. I can’t imagine having a different career, once it becomes so normal.

You mentioned the Democrats, and my one current events question, you know, you have your whole Ralph Nader Radio Hour, people can go onto the podcast app and subscribe to hear your thoughts on current events every week, so I didn’t want to ask too much about that. But I did want to say, it seems like the 2020 primary, I’m going to call it right now “the Nader 2000 primary” because we have Elizabeth Warren, who just came out with an economic patriotism bill, which I remember you fighting for with Pat Buchanan. Bernie launched Medicare For All, you started Single Payer Action in 2004. Everyone’s pushing for a Green New Deal, which was on the Green Party platform. Warren has a free college plan, you were for free college in 2000. People are saying, in speeches, it’s We the People, not “We the Corporations.” Anti-trust is on the rise, drug price gouging is on the front pages. Your ideas have gotten through. Obviously, your ’60s and early ’70s have gotten through, but even the second half of your career, about corporate power, about a two-party duopoly, about money in politics, about corporate malfeasance, is finally breaking through. How does it—what’s been your experience of seeing it breaking through?

RN: Well, it is early breaking through. The Democratic Party is still controlled by the old guard, Democratic National Committee, and now they’re trying to decide who to keep off from primary debates among legitimate candidates for the presidential nomination of their own party. So, we have a long way to go, but it does show you how fast public opinion can begin to change. I mean, these proposals come in at 60, 70, 80 percent support, which means they’re getting support from some people who call themselves conservatives, as well as people who call themselves liberals, and progressives, and if it all zeroes in on those 535 members of Congress, the most powerful branch of government is the smallest, the Congress, and we all know their names, 535, and they all want our votes more than they want the money of corporations. It can really be very transformative, fast. American history, in some ways, teaches that if you do something fast, you’re more likely to get it done. Harry Truman proposed universal healthcare, we’re still fighting for it. We proposed regulation of the auto industry nine months after Unsafe At Any Speed came out, the biggest industry in the country was under federal safety and pollution control regulation. And i say this because young people are impatient, and if you’re impatient, you’ll adhere to the proposition that once you’re on solid ground with what you think this country needs to be doing, move fast. Don’t have anybody tell you, “Well, look, Rome wasn’t built in a day, and it’ll take time, and don’t be too fast, and young, and impetuous.” And I might add that unless you see the universities and colleges coming alive, unless those auditoriums are jammed as they were in the ’60s, and early 70s, when speakers came to mobilize, to get names, to get internships, you’re not going to see the young generation turn around very much, and unfortunately, most colleges and universities now are dead zones, outside of the curriculum. Unless universities come alive, they start getting symposiums, conferences, teach-ins, speakers, agitators, it’s not likely that you’re going to get much of a thrust as occurred in the civil rights and environmental movements.

PD: I’d like to end by talking about two of your heroes. One hero: Upton Sinclair. I’ve heard that you met him at the White House. And I don’t think you’ve talked about it very much, and I just want to get it on the record, because I find it very poetic, because it’s the last great muckraker of his generation, handed across the century to the great muckraker of your generation. So, what was that like?

RN: It was quite memorable. So, we just passed the meat and poultry inspection laws, and they were sent to Lyndon Johnson to sign at a ceremony. And Lyndon Johnson knew he had to invite me. And Joe Califano, his chief of staff, said, “Lyndon Johnson would like to be the spotlight.” He’s a bit like Trump, nowhere near as bad. And he figured, if I was there, I would take some of the spotlight. So he invites Upton Sinclair, who is in a wheelchair, and very frail. I mean, Upton Sinclair, I mean, young people today don’t even know who he is. They may know who Eugene Debs was, because he’s in the history textbooks. Upton Sinclair almost won the governorship of California in the 1930s, and had he done that, it would have revolutionized politics around the country. He was done in by a terrible P.R. firm. It was one of the first dirty politics by a P.R. firm. He had also written all kinds of novels, all of which were justice novels, they were seeking justice. I mean, they weren’t going to win any Pulitzer Prizes, but they’re really gripping novels—just, dozens of these books. And of course, his novel, The Jungle, stimulated the formation of the Food and Drug Administration in the early 20th century. And so, I did go over to him, he was extremely frail, some pictures were taken. But I did see it like the passing of the torch. And a few months later, I think, he passed away. He should never be lost to history. He’s a remarkable advocate, tremendous determination and stamina, and you know, he did the electoral exercise of running for office, he did the book writing, he did the advocacy, he was a civic mobilizer, in many ways…

PD: Yeah, that turn of the century period, you have Ida B. Wells, what an amazing figure, Upton Sinclair, all of the progressive-era movements. I wish we had holidays to these people. I wish it was as strong in the culture.

RN: Well, the irony of it is that there are 1,000s of these people, writing great books and documentaries, but they don’t get any further attention, they don’t generate any congressional hearings or prosecutions, with a few exceptions, and they just drift away.

PD: I’ll end with another hero of yours. You have a poster of him up in the office, Lou Gherig. You were from part of the part in Connecticut, in the divide in Connecticut, that was not a Red Sox fan, but a Yankees fan, and the interesting thing about you being a fan of Lou Gherig, and correct me if I’m wrong and I’m reading too much into this in my poetic heart, a lot of what is inspiring about you, to me, is the aspect of showing up to work every day, of playing a lot of consecutive games, and it is interesting that Lou Gherig, and my favorite baseball player, Cal Ripken Jr.,were both famous not for hitting the most home runs, not for doing the perfect game, but for putting in the work, and I’d love to hear, close, with your reflections on Lou Gherig.

RN: First of all, he was a very honest, upstanding person. He never got drunk and caroused the way Babe Ruth did, and he never got the spotlight Babe Ruth did. But he was a great player. I think his lifetime batting average was about 330. But the thing that struck me the most was 2,130 games, he never missed one. And the only reason he missed the 2,131st game was because he was coming down with what we now call the Lou Gherig’s Disease. His neural motor systems were breaking down, and I never forgot that stamina. It’s really interesting. It’s the only picture I have on my wall. That’s the impact he had on a 7 or 8 year old kid. Plus, the fact that he was a winner [laughs]. He won a lot of games. And one of the greatest clutch hitters in the history of baseball. So, all of that was easy to translate into this civic drive for justice.

PD: Well, Ralph Nader, the Lou Gherig of civics, thank you so much for coming on the Current Affairs Podcast.

RN: Welcome, and go to Nader.org, you’ll get, automatically free, every week, seven minutes of agitation, otherwise known as my column.

PD: Enjoy, listeners.

Transcribed by Addison Kane.

If you appreciate our work, please consider making a donation, purchasing a subscription, or supporting our podcast on Patreon. Current Affairs is not for profit and carries no outside advertising. We are an independent media institution funded entirely by subscribers and small donors, and we depend on you in order to continue to produce high-quality work.