How To Write A Political Puff Piece

Vanity Fair teaches you how to make politics about personality rather than policy…

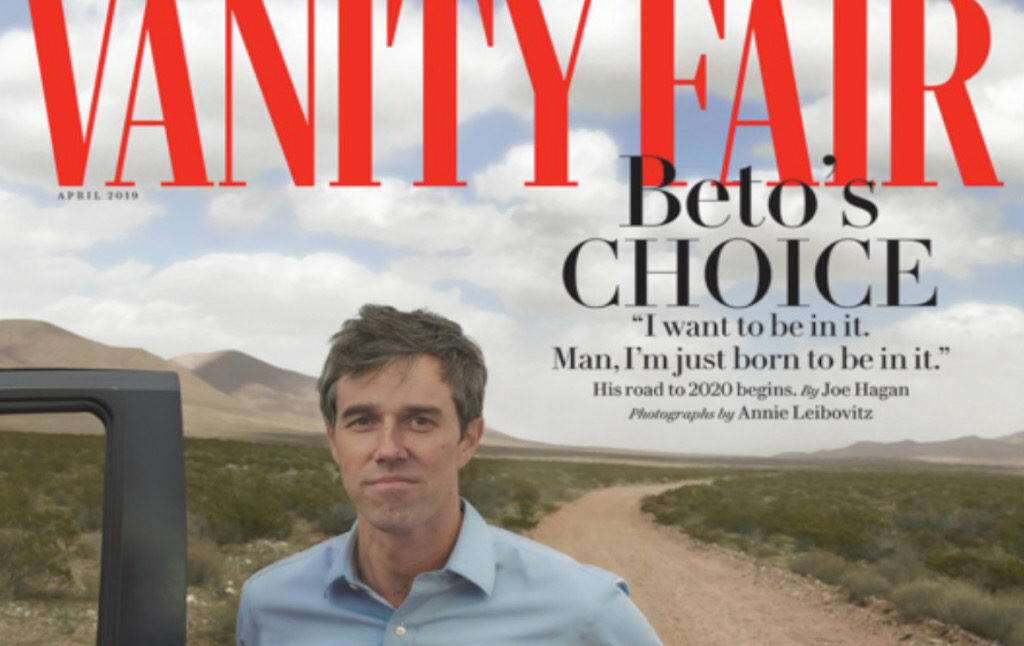

To coincide with Beto O’Rourke’s presidential announcement, Vanity Fair released a long personal profile of him as a cover story. It is accompanied by a series of warm and flattering pictures of O’Rourke from celebrity photographer Annie Leibovitz. It is a well put-together, if unsubtle, piece of propaganda, and it should be read by anyone looking to learn the art of the puff piece.

The cover photo features O’Rourke in jeans, by a truck, on a dirt road, with an adorable (if somewhat dejected-looking) dog. He has his sleeves rolled up. His collar is blue. When wealthy politicians want to cultivate an “I’m Just A Regular American Guy” image (or journalists want to help them produce this image), this is what they do: a magazine cover showing the politician wearing work clothes. You can find similar cover photos of Ronald Reagan and John Edwards:

(The Edwards profile was even written by Joe Hagan, author of the new Beto story.)

Vanity Fair, which does sometimes publish journalism, hasn’t put much effort into making this look like anything other than an unpaid campaign advertisement. Certainly, Leibovitz adores O’Rourke, and she speaks like a fan rather than photojournalist:

I was moved by his writing and who he was, and how he represented people he met. I can only respect someone who’s searching—someone who really is asking questions, and has the drive and the verve to get on the ground and go out.

The photos themselves are pure adulation. Beto making pancakes for his children. Beto playing music with them, Beatles poster and baby photos on the wall. Beto lounging barefoot with his son and his sad-eyed dog, Artemis, his coffee cup resting atop a Spanish-language version of I, Juan de Pareja. (Lest there be any doubt that he is raising his children bilingual.) Beto driving his truck, looking pensively at the road with hand on his chin. Beto squeezing hands amid an adoring crowd, signs begging him to run. Beto giving a speech in front of multiple American flags, as a cowboy looking on gives a thumbs-up. Beto’s daughter giving him a loving hug as the family visits a state park.

Family. America. Mountains. Home. The Flag. Books. Truck. Cowboy. Faithful Dog. Remember that elections are decisions about how government power will be used in ways that will either help or hurt a lot of people. What do these photos tell us about any of that? It’s no different from a car commercial encouraging you to buy a Chevy because you’ve seen it with attractive people on a mountaintop.

Hagan’s article itself is more of the same. It’s a big wet kiss, thousands of words about how energetic and empathetic and determined O’Rourke is. O’Rourke himself comes off as far less interested in the substance of policy-making than in the thrill of being on the campaign trail:

“[T]here is something abnormal, super-normal, or I don’t know what the hell to call it, that we both experience when we’re out on the campaign trail.” … [A]fter playing coy all afternoon about whether he’ll run, he finally can’t deny the pull of his own gifts. “You can probably tell that I want to run,” he finally confides, smiling. “I do. I think I’d be good at it.” The more he talks, the more he likes the sound of what he’s saying. “I want to be in it,” he says, now leaning forward. “Man, I’m just born to be in it, and want to do everything I humanly can for this country at this moment.”

“The pull of his own gifts” is a nicely euphemistic phrase—the “pull of his own ego” would be a less charitable one. But the article is like that throughout: Everything is framed so that the article portrays the most flattering possible picture of Beto for his “rollout.”

Current Affairs has previously examined O’Rourke’s record, and reached the same conclusion shared by others: It is unclear where he stands on many issues, he has shown a worrying tendency to abandon progressive values and side with Republicans, and he seems to be a man with much charisma and few convictions. Such people are everywhere in politics. But I do believe Hagan’s Vanity Fair profile can give us some useful lessons on how propaganda is made, and how the media drains politics of its most consequential parts and fails to ask the important questions.

Here, then, are a series of tips for producing your own Vanity Fair style coverage of politicians.

1. The Candidate Must Be All Things

He is intelligent, but he is fun. He is pragmatic, but idealistic. He is athletic, but scholarly. He is thoughtful, but decisive. He is bold and cautious, mellow and dynamic, tender and tough. Do not be afraid to present a self-contradictory or incoherent picture: Simply string together one positive anecdote after another until the candidate has achieved every positive quality a human being can possess.

For example:

Former girlfriends describe O’Rourke as curious, wry, bookish but adventurous. He usually carried a novel in his pocket, whether Captain Corelli’s Mandolin or The Sun Also Rises. Maggie Asfahani, an El Paso native who dated O’Rourke while he was at prep school and college, said he was somewhat difficult to know. “That’s kind of the mystique of Beto, is that he seems to be accessible,” she says, “but there’s just this layer of protection. I don’t think it’s because he’s hiding anything. I think it’s because he’s keeping a part of it to himself.”

Good. He’s brooding and mysterious. He is so deep and multi-layered that he can never truly be known. But hang on: What if people think he’s aloof and unrelatable? Well, that’s why you need another passage that portrays him as an open book, who isn’t afraid to show the public his full true self:

He came of age in a world of crumbling taboos over personal revelation, which has clearly peaked with Donald Trump, whose relentless Twitter habit has basically set the table for O’Rourke’s open-book style. Whether onstage or on Facebook Live or in person, O’Rourke has a preternatural ease. That openness is part of what he loves about campaigning. “I think that’s the beauty of elections: You can’t hide from who you are,” he says.

In Hagan’s profile, I laughed when I read a quote about how honest Beto is that I thought would be from someone who knew him, but turned out to be from Beto himself. Says Beto of Beto: “I haven’t seen a candidate who has just shared what’s on their mind and spoken as honestly and directly, without interference from consultants and pollsters, as we’re doing right now.” I’ve never seen a politician as honest as… me. That’s okay: You can quote the candidate as an authority on his own excellence. “If I bring something to this,” he says, “I think it is my ability to listen to people, to help bring people together to do something that is thought to be impossible.” Pop quiz: Do you ask him what the impossible “something” he’s bringing people together to do is?*

The candidate is “the endurance athlete campaigner, tirelessly knocking on roughly 16,000 doors,” who “drew inspiration from punk rock, everything stripped of artifice.” He shares his father’s “local globalism,” whatever that is. He is steeped in Mexican culture but a proud American. You get the idea.

2. Look How Much Of A Human He Is!

The meat of the profile is the candidate’s humanity. You need to show that he is a Relatable Human Person with an Actual Human Family. The family has no internal problems, the children are “freckle-faced and clever.” The key here is details: The candidate is wearing something you would expect an ordinary person to wear, or saying something ordinary people would say. Beto O’Rourke, for instance, uses the word “fuck” several times in his Vanity Fair profile. Typical elected officials do not swear. That’s what unvarnished outsiders do. The type of people who will Shake Up Washington.

The first time I meet Beto O’Rourke, he’s lounging on the front veranda of his house on a Sunday afternoon, barefoot in blue jeans and T-shirt, talking on his cell phone.

He has feet. He wears jeans. He can relax, but he does business. His net worth might be $9 million, but money hasn’t changed him. Hagan runs through O’Rourke’s full life story: growing up Texan, rowing crew at Columbia, playing in an unlistenable band, starting a short-lived alt-weekly, doing some business-y things, serving on the city council. There are little human details sprinkled throughout:

[O’Rourke was] weaned on Star Wars and punk rock and priding himself on authenticity over showmanship and a healthy skepticism of the mainstream.

Star Wars: a movie that humans watch. Punk rock—he’s not just a person, he’s a cool person. Skepticism. Authenticity. But what if he sounds too punk rock? People need to know he’s serious. Make it clear that he reads books (but that they’re cool):

Behind the door, in the O’Rourke living room, a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf contains a section for rock memoirs (Bob Dylan’s Chronicles, a favorite) and a stack of LPs (the Clash, Nina Simone) but also a sizable collection of presidential biographies, including Robert Caro’s work on Lyndon B. Johnson.

Oh good, not just The Clash, but Nina Simone. And big important books about big important presidents. Wait, but… books? He’s getting aloof again. Need more “family man” details:

His son Henry had a fever, and Amy had fallen asleep on the couch while Dora the Explorer flickered on the TV. There was a Stan Getz LP on the turntable and a plate of homemade scones in the kitchen.

His children get sick. They sleep. Dora The Explorer: It’s a show regular kids watch, in regular human families. Ooh, Stan Getz. Jazz. Jazz is for intellectuals. Cool intellectuals. But don’t worry, there’s a plate of warm scones. Homemade. Family. Kitchen table. Not too proud to make their own scones.

But do they spend all their time at home? No! Sometimes they go out to eat. But does he spend all his time with his family? No! He’s a man with important work to do:

It’s nine P.M. on a Thursday night and Beto O’Rourke is trying to manage a couple of life-altering and possibly world-historical political events while also driving his family home from a Mexican restaurant.

Do the children love him? They can’t bear to part with him.

“Dad, if you run for president, I’m going to cry all day,” he says.

“Just the one day?” asks O’Rourke, hopefully.

“Every day,” says Henry.

3. Fake Criticism

This is absolutely key. It is necessary to preserve the illusion that you are an actual journalist. You must therefore include lines that adopt the form of criticism but are actually praise. Try something like:

O’Rourke can appear almost too innocent to be a politician—too decent, too wholesome, the very reason he became popular also the same reason he could be crucified on the national stage. I tell O’Rourke that perhaps he’s simply too normal to be president. “Whether you meant it or not, I take that as a compliment,” he says.

If O’Rourke has a flaw, it is that he is just too good a person for politics. Too wholesome and all-American. One can wonder whether this passage would be written the same way if O’Rourke were a person of color. With his burglary and DUI arrests, would Vanity Fair be writing that he was “too innocent to be a politician” or would they be wondering whether someone with such a “troubled background” could find “redemption”?

How about this spectacular spin on his nondescript politics:

For some, O’Rourke can still seem politically indistinct, even slippery, but that may be part of his strategy. When asked if he’s a progressive, a question that will surely dog him in the weeks to come, O’Rourke hedges with the aplomb of Barack Obama circa 2008: “I leave that to other people. I’m not into the labels. My sense in traveling Texas for the past two years, my sense is that people really aren’t into them either.”… Positions on issues matter, of course, but they aren’t everything. O’Rourke also sells a kind of cult of personality of his own, offering himself as the David to Trump’s Goliath, a folk hero for our time.

Barack Obama in 2008 was noncommittal on many things, but he did at least say: “I am someone who is no doubt progressive.” O’Rourke is on a whole other level. But there’s also that incredible part: Well, maybe actual positions aren’t everything. Now, yes, you get the phrase “cult of personality,” but the author considers whether that might actually be a good thing, an effective way of countering Trump. Folk hero! David and Goliath! And yet: Nobody can accuse Hagan of being afflicted with Betomania. After all, he brought up “a question that will dog him” and did consider the possibility that Beto’s lack of positions on things could be a drawback. This is called “journalistic neutrality.”

4. Sweep The Icky Stuff Under The Rug

There are a number of bad things about Beto O’Rourke. He has implied that climate change is a major political priority, but he has been terrible on this issue before now. He pledged not to take any money from oil and gas executives, then violated his pledge. He voted to rescind the oil export ban, over the protestations of environmentalists, and now U.S. oil exports are set to surpass Saudi Arabia for the first time. He has said that “we can reject the false choice between oil and gas and renewable energy.” Except this isn’t a false choice: Fossil fuels have got to go, period, and O’Rourke clearly doesn’t understand the basics of what is happening or the scale of the threat.

There is so, so much more. When he was on the El Paso city council, O’Rourke infamously supported a plan by his multi-millionaire real-estate developer father in law that would seize and demolish large parts of a historic working-class barrio. The Border Farmworkers Center, “which provides a clinic, cafeteria, and safe haven for migrant workers,” would likely have been turned into a Walmart parking lot. A shocking marketing presentation for the redevelopment prog depicted the past and future of the district. The past was “an older Hispanic man in a cowboy hat, accompanied by the words ‘Dirty,’ ‘Lazy,’ ‘Speak Spanish,’ and ‘Uneducated,’ while the El Paso of the future was shown by pictures of a smart new SUV, Matthew McConaughey, and Penélope Cruz, accompanied by the words ‘Educated,’ ‘Bi-lingual,’ and ‘Enjoys entertainment.’” (This is called “saying the quiet part out loud.”) O’Rourke vehemently defended the project, and tried to push it through the council even though it directly financially benefited his family. As for the poor families who would have been forced out, O’Rourke said: “You cannot have change without disruption.”

O’Rourke’s record has been conservative for a Democrat, even though he lived in a deep blue district. (David Sirota’s investigation of O’Rourke’s record at Capital and Main is thorough and devastating.) He has voted with Republicans on bank deregulation, and he even “relied on a core group of business-minded Republicans in his Texas hometown to launch and sustain his political career.” O’Rourke used to suggest he supported Medicare For All, but has since made it clear that he has no interest in pursuing single payer healthcare. Even on his signature issue, immigration, where O’Rourke’s harshest critics say his “sincerity has been demonstrated repeatedly,” he has actually sided with Trump against immigrant advocates. O’Rourke broke with Democrats to support an act that allowed border patrol agents to be exempted from taking polygraph tests as part of their job application. Every other federal law enforcement agency required this, on the theory that otherwise you can end up with violent criminals enforcing the law. But O’Rourke wanted to make sure “CBP has the tools it needs to hire efficiently and effectively.”

This is what Rep. Luis Gutierrez said about the bill O’Rourke supported:

“Anyone who votes for this bill is voting to support and implement Donald Trump’s views on immigration, his desire to militarize our southern border, and his fantasy of a mass deportation force.”

Does any of this find its way into the Vanity Fair profile? For the most part, no. It’s completely absent. The development project, however, was an important and controversial part of O’Rourke’s political career, and so must be dealt with. What do you do when you’re stuck with an ugly episode like this? Well, everything can be spun:

O’Rourke, fluent in Spanish like his father, went door-to-door trying to convince residents the city would build affordable housing elsewhere… A local historian and activist, David Romo, accused O’Rourke and his allies of destroying buildings of historic significance to Chicanos… The city opened an ethics investigation, and though O’Rourke was cleared of wrongdoing, he recused himself in the public debate and from voting on it… In the end, the plans collapsed because the economy cratered in 2008 and capital dried up. But the controversy stuck to O’Rourke, his original sin. O’Rourke says perhaps his biggest mistake was making an enemy of David Romo, who has become the source for a wave of negative stories.

The empathetic O’Rourke traveled the town to speak personally to residents. But one angry activist accused him of destroying historic buildings. O’Rourke behaved ethically, but nevertheless was tarred with an “original sin.” There you go.

Even O’Rourke’s two arrests are dealt with sympathetically. His DUI was an act of chivalry, taking a girlfriend home, and Hagan tells us that O’Rourke was so thoughtful he gave the woman cab fare when he was arrested. The burglary arrest is dismissed in a parenthetical: “during which time he was arrested for ‘attempted forcible entry’ at the University of Texas in El Paso after tripping a campus alarm one night.” Boys will be boys. The word “tripped” is masterful: makes it sound like he tripped. An accident. Could have used “set off a campus alarm,” but that might have made people curious. As for questions about whether O’Rourke’s father’s political connections may have influenced the dropping of the charges, Hagan is uninterested in pursuing them. This is how you do it: Mention bad things when you absolutely have to, but slather your account excuses, mitigation, and euphemism.

5. Try To Keep Politics Out Of It

This is a piece about the politician’s human side. His dog and his fondness for The Odyssey should take up far more space than anything about his ideas on healthcare, housing, or environmental policy. You can’t let the politics get in the way.

You are allowed to let the politician say some vaguely political things. A healthy number of context-free platitudes are important in making it clear that he’s a Big Ideas man. Just do not be attempted to ask him to get specific when he muses.

At this, Hagan excels, and you can learn from him. When it comes to climate change, Hagan quotes O’Rourke saying that he supports a Green New Deal “in spirit.” He does not press O’Rourke on what on Earth this means. Nor does he bring up O’Rourke’s voting history or his failure to previously lead on this issue. He does not ask O’Rourke why he voted with the Republicans so many times, why he provided PR for a Republican congressman that helped him beat a Democrat, or why he tried to turn a workers’ center into a Walmart.

Instead, we find out that O’Rourke doesn’t like to be against things:

“I just don’t get turned on by being against,” he says. “I really get excited to be for. That’s what moves me. It’s important to defeat Trump, but that’s not exciting to me. What’s exciting to me is for the United States to lead the world, in making sure that the generations that follow us can live here.

If you were a journalist, you might ask “Ok, but what are you for? What will you do to make sure of that? And are you not against some things? Mass incarceration maybe? Injustice?”

Remember, though: You are not a journalist. You are a puffer. Your job is to write down the quote, add something about how the dog looked up and seemed to agree with him, and then send it off to your editor.

Now Try It Yourself

Ok, everyone. You’ve done the reading, you’ve heard the lecture. Now it’s time for the exercise. Write a profile of a fictitious version of yourself, in which you observe the above rules. Follow the Hagan method to the letter, and you’re on your way to becoming a top-flight campaign journalist, or even a presidential biographer!

Here’s one I made earlier:

THE ROBINSON CONUNDRUM:

To Run Or Not To Run?

A Decisive Lawmaker Is Wracked By Inner Conflict

When I meet Nathan J. Robinson, he is making waffles for homeless children at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“Will you run for president?” a 10-year old Chicana girl asks, with imploring eyes.

“We’ll see, we’ll see,” he replies, his manner casual and yet serious, playful yet thoughtful. Robinson seems as if his mind is fully on the children. And yet it is also elsewhere—on loftier things, no doubt. In person, he is affable and calm. Yet there is a tension in him, an an irrepressible excitement. He is mysterious, brooding, yet somehow open and relaxed. He is present and yet absent, a man who displays his full self and yet maintains a certain elusiveness.

At home, Robinson divides his time between doting on his children and thinking deep thoughts. Yet while he is bookish, he is anything but aloof. His shelves are filled with the classics—he takes Marcus Aurelius to bed, a habit his wife teases him about—and his casual use of Latin betrays his strong working knowledge of the language. (“Carpe diem,” he says offhandedly. “E Pluribus Unum.”) For every volume of Diderot and Cervantes, though, there is a book about hair metal, feng shui, tennis, or Science. He would just as rather curl up with the autobiography of Mötley Crüe as the collected poems of Eliot. (“Do I dare disturb the universe?” he asks me with a wink.) His taste in film is equally eclectic. He says he enjoys everything from Orson Welles to the Farrelly Brothers. “What people don’t know about Welles,” he says, “is that Touch of Evil is the real magnum opus. They all think it’s Kane. It isn’t.” One can imagine him sitting down with the director himself to talk film, perhaps over saumon fumé at Ma Maison. “Not that I get much time for cinema these days, with politics and all that.”

Yet he makes time in his hectic congressional schedule for his original passion: prose. “I am working,” Robinson says offhandedly, “on a two-volume history of microfinance. Do you know about the origins of digital currency? Crypto is not just the future.” The depth of his economic knowledge is instantly apparent, but he downplays it. (“I am just a layperson with some degrees,” he says, waving away my suggestion that he could have had a distinguished academic career.)

Yet the scholar is also an athlete. During his Ivy League years (MA, JD) at a university he modestly declines to name, he was on the golf team. “Golf?” I ask. It seems a strange choice. He chuckles and shakes his head. “Four years of high school football had been enough.” He had been winning too much, the challenge was gone. “Guys like me should golf more. It gives you humility, you know?” Indeed, humility saturates his conversation. He doesn’t like to name-drop. When he says that his friend “Cornel” once told him that the presidency was the only office worthy of his talents, he doesn’t mention he means legendary intellectual Cornel West.

Robinson does have his weaknesses: animals and children. “I can’t help it,” he says. “When a kid wants a ride on a swing, I’ll drop all the political stuff and give ‘em a push.” His own children, of rosy cheek and plucky disposition, call him the “Cool Dad,” though he shrugs off the label. “They won’t be saying that in a few years,” he chuckles. His love of animals reveals a gentle spirit, one possibly unsuited to the brutality of a nationwide campaign. “I am a natural-born cat person,” he discloses sheepishly. “Though I also love dogs.” His stalwart labrador, Mueller, is hearty and full of vim.

For a politician so steeped in the issues of our time, he spends little time talking about politics. “People don’t care about politics,” he says. “They care about being brought together. They don’t want some politician telling them how to live their lives.” Nevertheless, I say, as president he would have to make hard choices. “Here in Louisiana we have a saying: Hard choices are only hard if you can’t make choices. The choice is simple. The choice is change.”

“Change?” I ask. “Isn’t that somewhat bold?”

“Maybe it is,” he says. “But I have always had a weakness for boldness. If people don’t like it, that’s just who I am. Fuck.” Yet one senses that the change he seeks carries with it a certain stability. It is youthful, yet tempered by the wisdom that comes from a life spent struggling to find purpose. When I ask Robinson how he can balance his ambition with his pragmatism, he replies:

“Shared sacrifice. Bringing people together. Middle class jobs. Access to affordables. A different kind of greatness. That’s the problem: We don’t know who we are any more. Who am I? We know who America is. And yet somehow we don’t. That’s what I bring to the table. Shit, it’s not that difficult. Why not try leadership? Why not try hoping for a change, without changing your hopes?” He has worked himself up into a passionate speech, and one can tell he is made for the stage.

But will he run? Robinson is coy. “That’s for my wife to decide,” he laughs. Beside him, she smiles. “I didn’t choose this life,” Robinson states flatly. “The life chose me.” It feels true and yet somehow not, a winking sleight-of-hand more honest than any fact.

*Answer: You do not.